Open season on scholars of race

They are facing both personal attacks and institutional censorship

The resignation of Claudine Gay as President of Harvard was an extraordinary success for a right wing movement that targeted her not because of her views about Israel, or campus speech, but because she was a scholar of color who studied race, supported DEI initiatives as an administrator in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd, and, they believed, was selected as a diversity hire. The success emboldened this movement to keep going, targeting other scholars who study race, primarily scholars of color, in visible institutions.

Chris Rufo, who coordinated the attack on Gay, announced he was creating a fund to investigate academics for plagiarism. We are now seeing the fallout of this movement. Rufo recently posted accusations against Christina Cross, who is an untenured Assistant Professor of Sociology at Harvard.

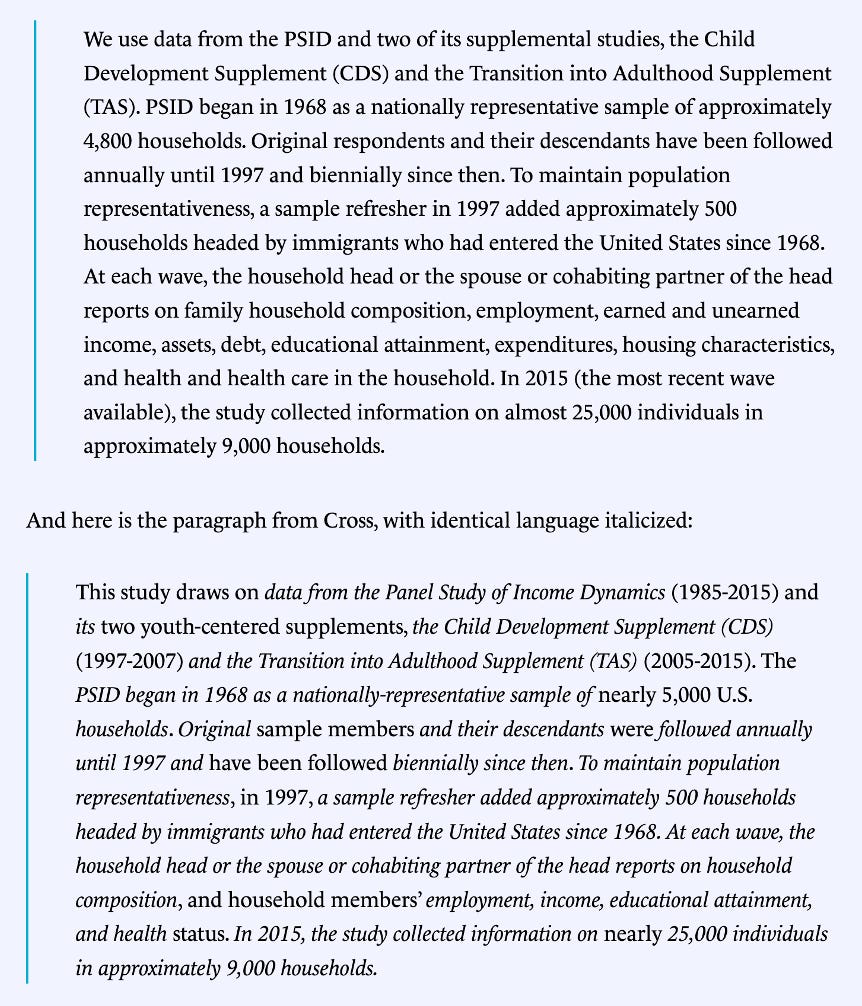

Full disclosure: I’ve met Christina Cross when I ran a symposium, for which she wrote an excellent paper. If you want to assess the quality of her research, just go ahead and read it or her public facing research. If you do so, you will be doing something that Rufo and his allies refuse to do, which is to engage with the substance of the research they are trying to erase. Instead, the following is Rufo’s “most serious allegation” of “plagiarism” that he leveled against Cross, where he alleged she stole language from Stacey Bosick and and Paula Fomby. Bosick and Fomby’s text is first:

This is not plagiarism. Set aside that there is no accusation of substantive stealing of ideas. There are simply only so many ways you can describe a dataset’s name, survey population, and dates of data collection. Language like “sample refresher” is a standardized technical term. If this is your standard of plagiarism, then everyone using widely-used public datasets is a plagiarist if they repeat the same dataset names, variables and description of data collection.

I reached out to one of the authors of the first paragraph, Paula Fomby (who has since co-authored with Cross and served on her dissertation committee). She pointed out that it would have been best practice for Cross not to cite her work, but instead to cite the PSID user guide (while noting that Fomby herself neglected to do so). She also said: “These are similar descriptions of a publicly available data resource, and I am not troubled by the overlap.” The other author, Stacey Bosick told The Harvard Crimson that she wasn’t “concerned that any path-breaking ideas have been stolen here” but was “more concerned about the disproportionate surveillance of black scholarship.”

My God, the standalone reoccurrence of “its” is treated as plagiarism. The use of the *actual names* of datasets is treated as plagiarism. If one scholar says “data from the PSID” and another says “data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics” thats plagiarism? How can anyone take this seriously?

Again, this is Rufo’s strongest claim!

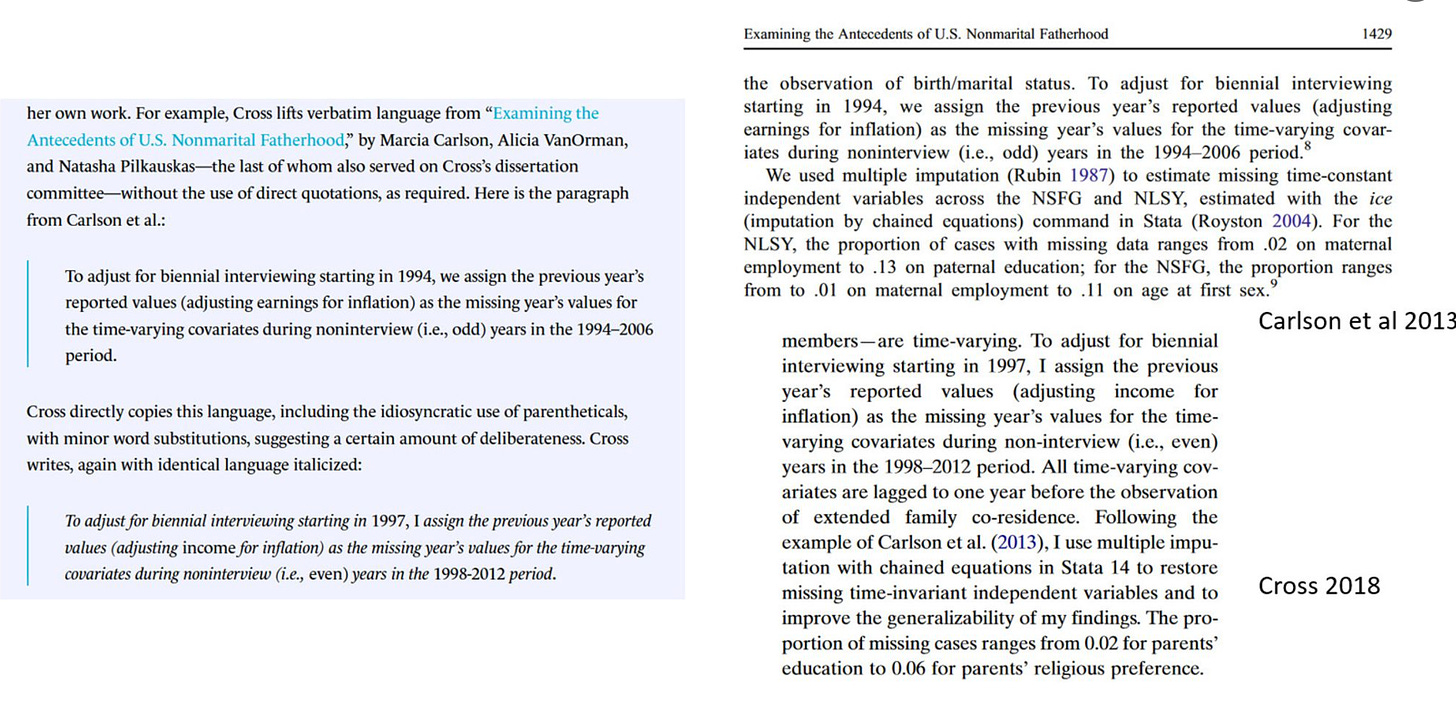

He also accuses Cross of plagiarizing others in her description of research techniques. Again, there is only so many ways you can describe standard methodological techniques because there is standard technical language you can’t easily paraphrase. Imagine describing “ordinary least squares” as “normal smallest plane figure with four equal straight sides and four right angles” to avoid being accused as plagiarism. Its a bit silly! And as Professor Philip Cohen pointed out, Cross does cite the source that she is accused of plagiarizing two sentences later.

I also reached out to Marcy Carlson, of the Carlson et al. that Cross is accused of plagiarizing. She is a senior scholar in the field of demography that Cross works in, and so surely has some standing here. Her response: “This is far from academic plagiarism. Cross is simply describing a national data set, and she cites our paper in the very same paragraph!”

A group of senior scholars who have served as leaders of the type of public dataset that Cross was describing, including PSID, also released a statement that explains why, in their field, what Cross did is commonplace and not considered plagiarism:

We are deeply concerned about this false allegation of research misconduct. The purpose of these public data resources is to provide a shared platform for the conduct of innovative and rigorous research. They are a public good. In that context, we fully expect that researchers who use these data will accurately and consistently describe and represent these resources, exactly as in the manner reported by Dr. Cross. Part of the alleged misconduct was Dr. Cross’s accurate usage of a data resource’s proper name. We, of course, do not want researchers renaming public datasets, just as astronomers would not want researchers to rename the Hubble Telescope. In addition, basic descriptions of a dataset’s sample, measures, changes in sample size over time, and the study background need to be discussed and described consistently. It’s not simply that Dr. Cross’s writings do not constitute plagiarism. Rather, her description of a large public dataset in this standardized way is simply good research practice - helping to ensure replicability and transparency. Indeed, this is a common practice among our user communities, and it should remain so to ensure high quality scientific research.

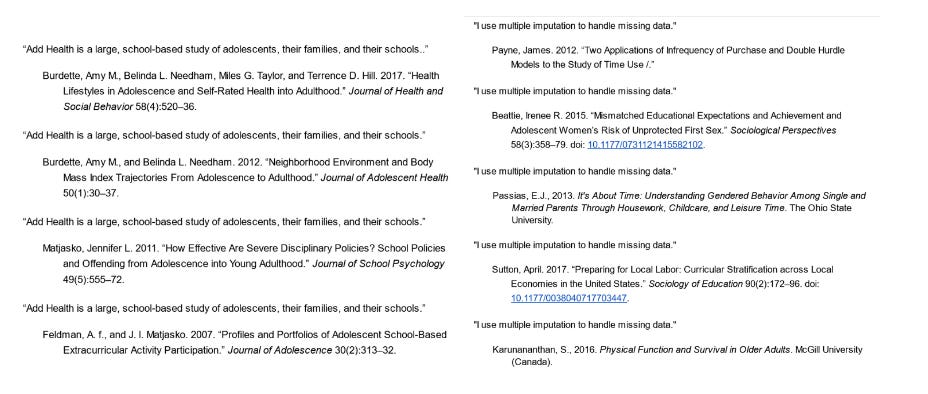

If you don’t work work in these fields, the idea that being very consistent in language when discussing datasets or research techniques might sound like a dodge, but its really not. Professor Philip Cohen provided examples of the exact same wording describing datasets and research methods across different demographers. Cross is not being held to some lower standard - she was applying standards in her field.

Jonathan Bailey runs the website, Plagiarism Today, whose entire purpose is to expose actual cases of plagiarism. He reviewed the claims at the request of the Harvard Crimson and concluded: “I don’t see evidence of an issue” and “This doesn’t even warrant a correction, let alone a retraction or firing.” Similarities in text were “relatively meaningless overlaps that wouldn't likely catch anyone's eye doing a neutral plagiarism analysis.”

Building the plagiarism brand

If you have been paying attention, the strategy and tactics have been been all too predictable.

Rufo builds negative brands. That is what he does. He was fantastically successful in building the CRT brand. In 2021 I wrote about Rufo’s capacity to convert bullshit claims into negative brands, and why it matters:

Converting bullshit into a brand simplifies things. Brands create heuristics that upend rational thinking. Heuristics are cognitive shortcuts that means we don’t have to think through a problem, or critically assess a source of information. Once we are cued by the appropriate heuristic - CRT! - we accept or reject uncritically the information that follows.

Plagiarism is a brand now. It does not matter how fair or accurate the accusations. Most of Rufo’s readers will accept his claims at face value, since they feed a narrative they already believe in. (If you doubt this, look at the replies to his tweets). When Gay resigned, I warned that:

neither the media nor universities are equipped to deal with politically motivated accusations of academic misconduct. Such accusations can be made by anyone, even anonymously, and put the academic under a cloud while a university or journal investigates.

The game plan is simple. Selectively target scholars who study race, who will be primarily scholars of color. Launch an anonymous accusation. Then report on this as newsworthy in right wing media, hoping the mainstream media will pick it up. On social media if will find its own audience. In less than 24 hours, Rufo’s post had over 800,000 views, boosted by far right luminaries such as the guy who pushed the Pizzagate conspiracy. Elon Musk replied to one of Rufo’s post, which dramatically increases the spread of the false claims.

Institutions don’t have to voluntarily play along. I can tell you with a very high degree of confidence that Cross will not be punished for the simple reason that what she did does not constitute plagiarism in any meaningful sense. But while Rufo would prefer to see such academics removed, the strategy still works even when they stay in place:

If the researchers are cleared, the accusers will argue that the institutions themselves are corrupt, and “accused plagiarist” is not a smear that ever permanently fades. It is, therefore, an accusation that is cheap and easy to make, and will generate some sort of effect as long as a motivated audience treats the accusations as credible.

The media, and especially the New York Times, helped to create this problem. They co-produced Rufo’s plagiarism brand with their obsessive coverage of Gay, in a way they did not cover public figures facing similar accusations, such as the President of Stanford or Justice Gorsuch. Now, they can help by a) ignoring such accusations, and b) covering the movement that Rufo participates in to eliminate discussion of race on campus and c) stop treating Rufo and his ilk as reliable sources.

Institutional chilling of speech

The brings me to my second example, which is Alabama. The state just passed a bill prohibiting funding for DEI programs on campus and in government agencies. It also blocks the use of funds to pay for scholars of CRT to speak on campuses. The law mirrors the language of prior anti-CRT bills in that it blocks any teaching of “divisive concepts,” which can include assigning “fault, blame or bias.” The language of “divisive concepts” comes from Trump’s executive order prohibiting training programs related to race, an order that Rufo inspired.

The breadth and scale of the law is extreme. A similar law in Florida led to the closure of DEI offices, and Pen America rated the Alabama law as “even more restrictive.” It relies on vagueness as a mechanism to chill speech. Reading about the law, I have no idea whether it is legal for me to give a talk on an Alabama campus about my research on the relationship between race and administrative burdens. Given that uncertainly, researchers on campus have little reason to invite me.

For faculty and researchers who study race, they are left with some hard choices: a) present the research consistent with their academic training, hoping the university will back them up, b) present on the the topic of race in America consistent with the law, but without any real certainty on how to do that, or c) simply skip coverage of the topic. Option C is a lot easier, and one that faculty in Florida are already taking. The net effect is that certain topics are technically legal to talk about, but effectively censored given the vagueness of the guidelines and the erosion of institutional supports.

The New York Times coverage of the new law was effective, pointing to lobbying by the Claremont Institute, which suggested that wokeness was running amok in Alabama. The Claremont report was written by Scott Yenor, a right wing academic from Boise State University. Yenor also featured in an excellent deep dive by Nick Confessore on the role that Claremont has played in targeting discussions of race on campuses. Thomas Klingenstein, the chair of Claremont and a top GOP donor, lamented the way that the death of George Floyd had directed attention to issues of discrimination on campus.

“Rhetorically, our side is getting absolutely murdered,” Mr. Klingenstein wrote to Dr. Yenor and another Claremont official. “We have not even come up with an agreed-on name for the enemy.” One problem, Dr. Yenor reported to his colleagues, was that many lawmakers were reluctant to take on anything called “diversity and inclusion.” Terms like “diversity,” he argued, needed to be saddled with more negative connotations.

Claremont, like Rufo, seeks to strategically use language and messaging to frame attention to diversity and race as inherently problematic, with the wider goal of erasing attention to those topics on campus. In emails, Yenor stated “The core of what we oppose is 'anti-discrimination.' That is too much of a sacred cow.” And so, they emphasize the ideas of “wokeness” or “CRT” as radical values in order to target race and DEI. “Bans on CRT and its associated ideologies are a lot of smoke or boob-bait for the bubbas” said Yenor in one email.

At the same time they try to co-opt people who think of themselves as liberal to participate in the purge, by pretending to care about academic freedom. Yenor himself benefited from a university that defended his academic freedom after he declared that women were “more medicated, meddlesome and quarrelsome than women need to be” because of feminism. He also urged that Claremont defend Amy Wax, the racist University of Pennsylvania professor, by saying: “You are appealing to lefties, so you should target them, both on free speech grounds and on grounds that implicate their fears.” A colleague asked Yenor if firing faculty like Wax might not be good, so red state legislators could follow suit

“But don’t we want this to happen?” Dr. Azerrad asked.

“Yes,” replied Dr. Yenor. “But your audience doesn’t want it to happen.”

These are not popular ideas. They depend upon the type of money and personal access to academic leaders that politicians and the very wealthy can leverage. Which is what Claremont did in Alabama.

In Alabama, they partnered with a group called Alabamians for Academic Excellence and Integrity. Jeff Sessions, the former U.S. attorney general and a supporter of the Alabama group, was among those who provided funds for a Claremont report, “Going Woke in Dixie?,” that focused on Auburn University and the University of Alabama. After it was released last summer, according to another email, Samuel Ginn, a wealthy Auburn alumnus and donor to both the school and Claremont, confronted the university’s president, Christopher B. Roberts, and pressed him to address the report’s findings. “The president then told him, ‘Things will change,’” a Claremont fund-raiser wrote to Dr. Yenor and other officials there.

Even as these actors portray scholarship on race as radical, their own views are deeply and truly radical and a danger to American democracy. John Eastman, one of the leagl architects of Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election, is a long-time member of the Institute who remains in good standing. According to The Guardian, Yenor is a member of a “men-only fraternal order which aims to replace the US government with an authoritarian “aligned regime”, and which experts say is rooted in extreme Christian nationalism and religious autocracy.”

Individual and institutional attacks

Rufo interspersed his harassment of Cross - for, uh, criticizing an attack on the US Capitol on January 6 - with celebrating the passage of the Alabama law. What other themes are common between the two cases?

The Alabama law and Rufo’s attack on Cross represent different prongs of a collective strategy, combining individual and institutional attacks as part of a one-two combo. Institutions are much more vulnerable to the attacks on their faculty when they themselves are under attack. Yenor and Rufo have the same goals, and Rufo has singled out Yenor for praise:

I’ve been working on university reform and I’ve made great alliances with many conservative professors who are starting to push back. I think someone who’s done a very good job at this is Scott Yenor, who’s a public university professor in Idaho and a Claremont Institute fellow.

Beyond the connections between the players in this movement, which crucially involve a lot of donor money, there are some other lessons.

First, these are examples of backlash, of a post George Floyd politics. After the outrage associated with the death of Floyd, it seemed for a passing moment that American institutions in government, business and academia were paying real attention to historical problems. The most meaningful policy result, however, has been to mobilize the right wing to both mischaracterize such efforts and go after institutional nods to fairness they previously saw as unattainable, such as DEI offices. Contrary to what you have been told about wokeness run amok on campus, it is now much more professionally risky for scholars to study topics related to race, or to be public facing scholars if they do so, than it was before 2020.

Second, the goal is to feed a culture of fear within research institutions. Knowing that you are going to be placed in the crosshairs by a bad faith antagonist is intimidating. Rufo published his accusations against Gay, and then Cross, in City Journal, a media outlet of the right wing Manhattan Institute. This tactic reflects an ongoing pattern of a new right wing media seeking to intimidate and cancel scholars that do not share their views, and especially those who study race. If you do not study this topic, or are not a scholar of color, or are not critical of right wing ideas, you can stay safe in the academic cocoon. Which is what they want.1

Rufo spent a considerable amount of time searching for any professor who disagreed with him, and quote tweeting them to his 636K followers. The goal is to silence dissent and pushback, and delegitimize academia, but this is harder to do when more scholars speak out, and when institutions back them up.

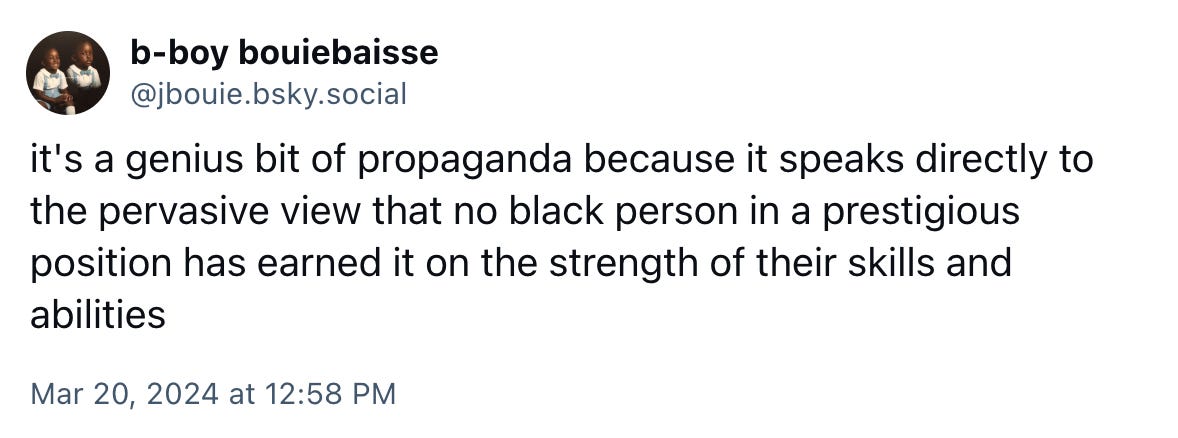

Third, the message is that the topic of race, and the Black scholars that disproportionately pursue the topic, simply do not belong in elite institutions. The mode and nature of the targeting feeds into prejudices, clearly felt by those doing the targeting. On BlueSky, Jamelle Bouie wrote “the key thing here is that "plagiarism" here means "being a black person in a prestigious position"":

The mere presence of scholars of color is taken as clear evidence of a sign a decline of institutional merit (compared to the good old days, when you could get a job based on the strength of a letter of recommendation from a mentor at an elite institution).

Fourth, the accusers are interested only in the accusation, not the evidence. Those who perceive certain scholars or topics as inherently illegitimate are using academic misconduct accusations to attack them. They do not actually care about the validity of the claims, or evidence that might rebut them. Under such assumptions, there is no way for scholars to defend themselves. It does not matter how good their work is, since Rufo et al. refuse to engage on the substance or quality of the research. They conflate it as CRT work, implying that the work is subjective and not “real science.” But Cross (like Gay) does fairly sophisticated quantitative work, based on data that others can use and contest, and which follows standard practices for careful empirical work.

Awards, accomplishments and recognition for the quality of scholarship (and Cross has many) are viewed as reflective of a wider corruption. (Of course, if you want to become a scholar or commentator supportive of right wing ideas, there is a gravy train of support ready for you, regardless of your accomplishments). The opinions and expertise of the alleged victims of the plagiarism, or senior scholars that can credibly explain norms in the field, will be discounted or ignored. If the university takes no punitive action, this will be taken as a measure of the corruption of the institution, rather than proof of innocence. The Witchfinder General has the first and last word.

At some point, the liberal institutions that say they support free speech and open inquiry are going to have to decide how often they will fall for these strategies, whether they will be part of the witch-hunt or not, and when they will fight back.

There is also a degree of fear in critiquing what is going on. After I posted this piece, Chris Rufo responded, suggested I was unworthy of my professorship at Georgetown. A conservative scholar who has targeted liberal scholars with plagiarism claims (later dismissed) also critiqued me. So, if you hear accusations of academic misconduct being made against me at some point in the future, you will have a pretty good understanding of why they are being made!

This is so frustrating and so scary. Why would anyone in the media listen to Rufo since he has no credentials to criticize anyone's research. This type of harm also happens to women in academia in any discipline. When I went up for full professor I had the unanimous support of my department as well as the Dean of the Business School. However, the chair of the school-wide Promotion & Tenure Committee had a reputation of not approving females for promotion to full, since he believed they were "unworthy". He intimidated other members of the committee so the vote was split. While I also had the near unanimous approval of the Provost's Advisory Committee, the Chair of the school-wide committee went to the Provost and told her that I had plagiarized some sentences and paragraphs in my published research. His argument was that I used some sentences and paragraphs from older articles I had published in more recent articles, and since I had to sign away my copyright to the journals, I had violated copyright and plagiarized. The Chair was an economics professor and didn't publish in business-related journals. I met with the Provost and demonstrated that most business journals (at the time), including the ones I published in, did not require the author to sign away their copyright and that I was being accused of plagiarizing my own work. I also speculated on how I might write an article for the Chronicle of Higher Education discussing the discrimination against women in higher ed promotions. My congratulations letter was slipped under my office door that evening. The Rufo's of the world don't want free speech and want to force everyone to abide by their point of view. Unfortunately, it's a battle that never ends.