How to think about race and administrative burdens

Tools policymakers can use to address racialized burdens

Administrative burdens limit access to resources and generate negative experiences of government. A related concern is that these burdens reinforce patterns of inequality. Indeed, the first formal guidance the the Biden administration offered on reducing administration burdens was in an executive order on racial equity. This reflects the obvious normative concern that state actions should not systematically exclude or generate worse experiences for some groups relative to others.

There is also the empirical question of how, and to what degree, this happens in practice. While not pretending to offer a comprehensive account of the topic, my views on the relationship between race and burdens reflect what I’ve learned through my research, and I’m going to share some recent examples, as well as a positive story about how the IRS has committed to reducing racialized burdens in the tax system.

A simple way to think about how the state generates burdens is to look at it from different levels: macro level (think policy design, institutional practices), meso level (organizational practices and norms, implementation guidance), and micro level (discretionary actions, especially in front-line implementation). Different levels will be connected, but each offer a distinctive lens to think about the origins of burdens.

Racial resentment and policy design

One reason policymakers might be more inclined to infuse burdens in policies is to make them less accessible for groups they think the public views as undeserving. So it’s useful to look at how public thinking about burdens are shaped by race.

We already know that the public significantly overestimates the degree to which such programs are used by Black Americans, and that White Americans are less supportive of safety-net programs that are perceived as used more by Black Americans. New research suggests that this racialized opposition also extends to administrative burdens. In an article published in Health Affairs, Simon Haeder and I surveyed more than 4,000 people about their “burden tolerance” - their willingness to impose burdens - in Medicaid and SNAP. Burden tolerance was measured by asking respondents to choose between specific program implementation choices, some of which would lead to more burdens than the other, e.g. frequency of re-enrollment, requiring in-person interviews, or work requirements. (You can also read responses to our paper by Carolyn Barnes, and Leighton Ku.)

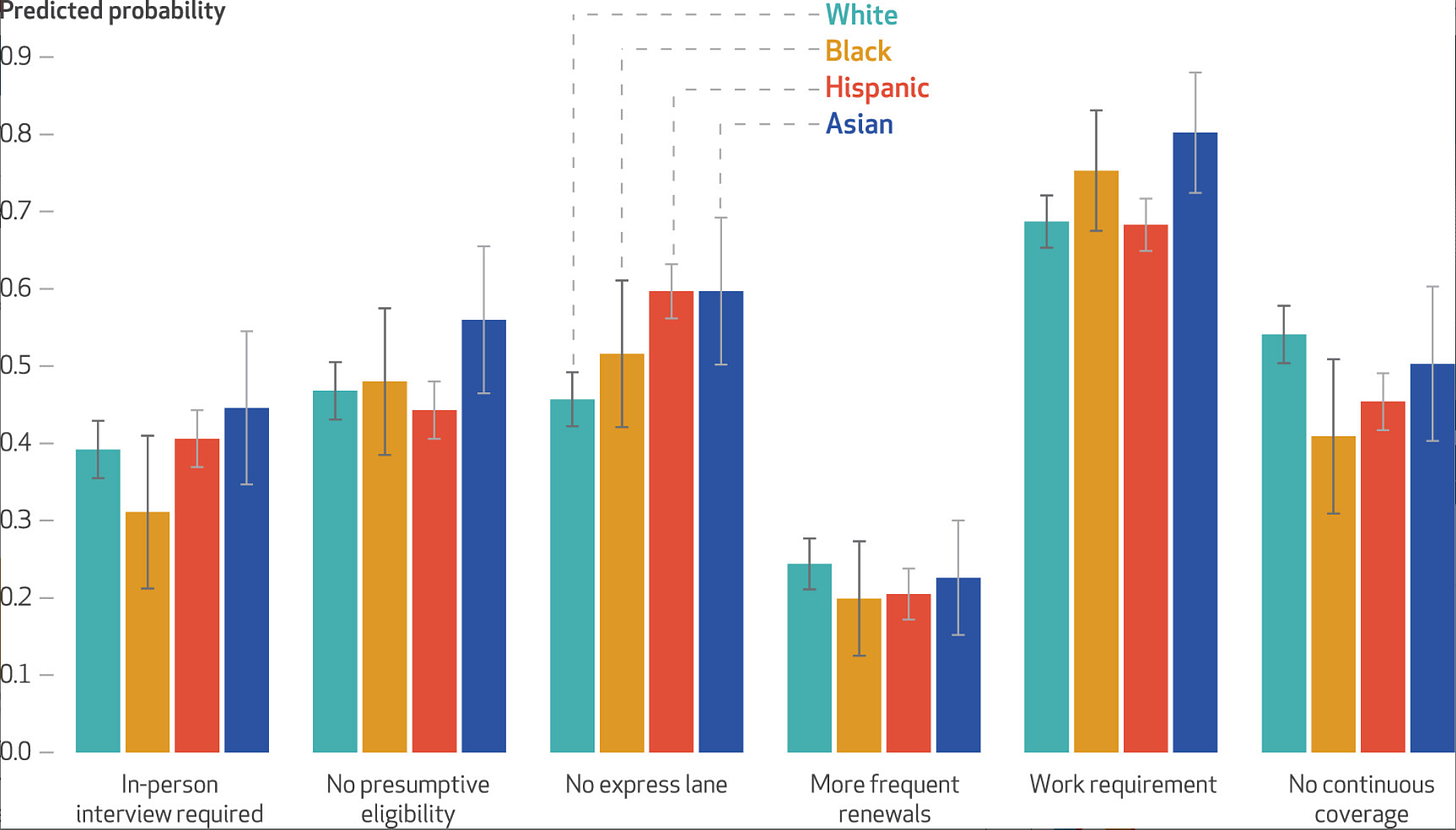

We tried to get at race in a number of ways. We included experimental treatments that primed respondents to think about the effects of burdens on race and class. We identified the race of the respondent. It turned out that these variables did not matter all that much. The first figure below shows that people vary considerably in their support for different administrative actions that would increase burdens. For example, work requirements have broad support but compelling people to renew their benefits more frequently does not. But we don’t see significant difference in support for burdens by race.

Figure 1: Predicted probability of support for administrative burdens in Medicaid, by respondents’ race and ethnicity, 2022–23

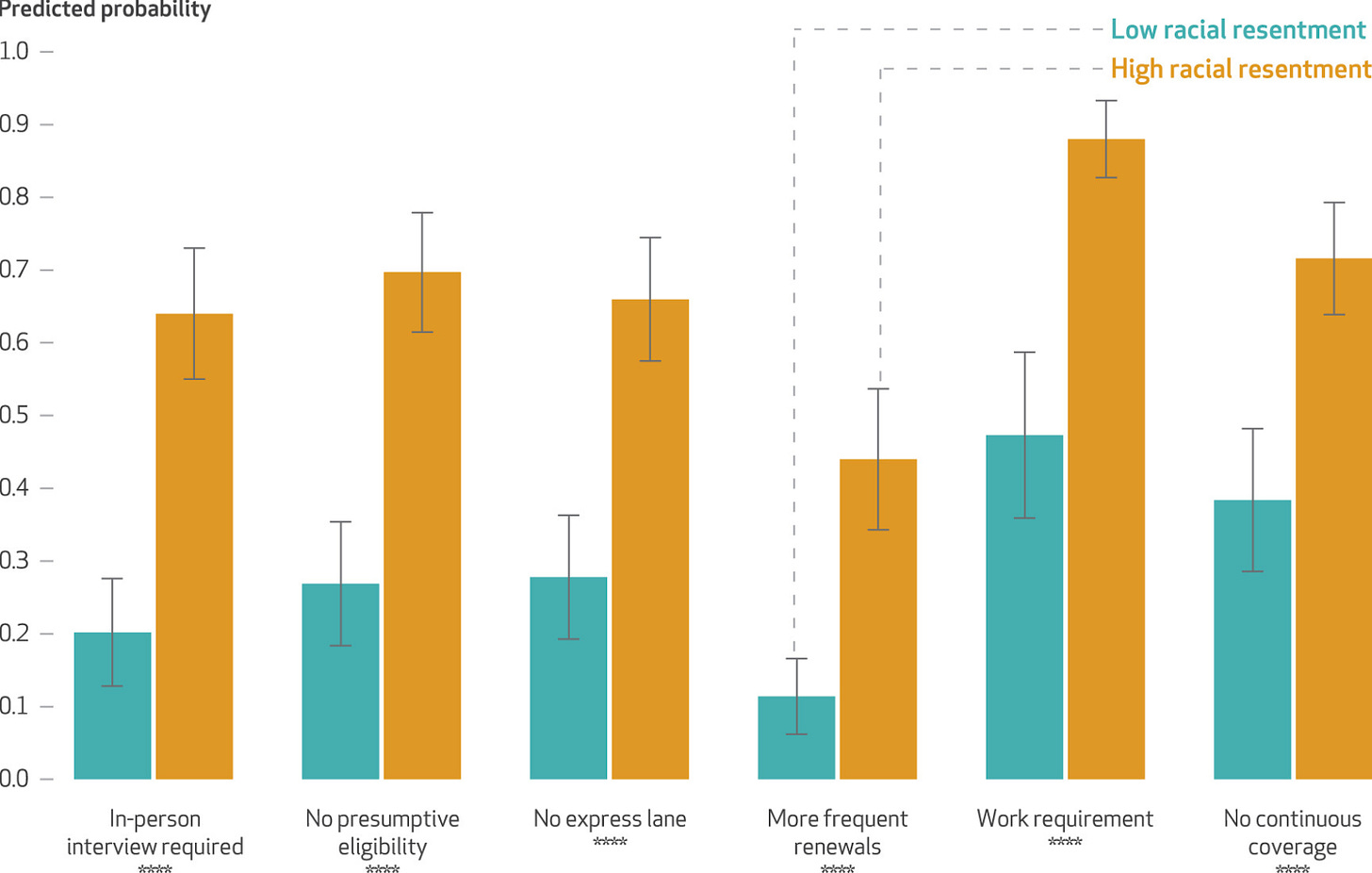

However, Whites who scored high on racial resentment were a lot more supportive of burdens.

Figure 2: Predicted probability of support for administrative burdens in Medicaid, by level of white respondents’ racial resentment toward Black people, 2022–23

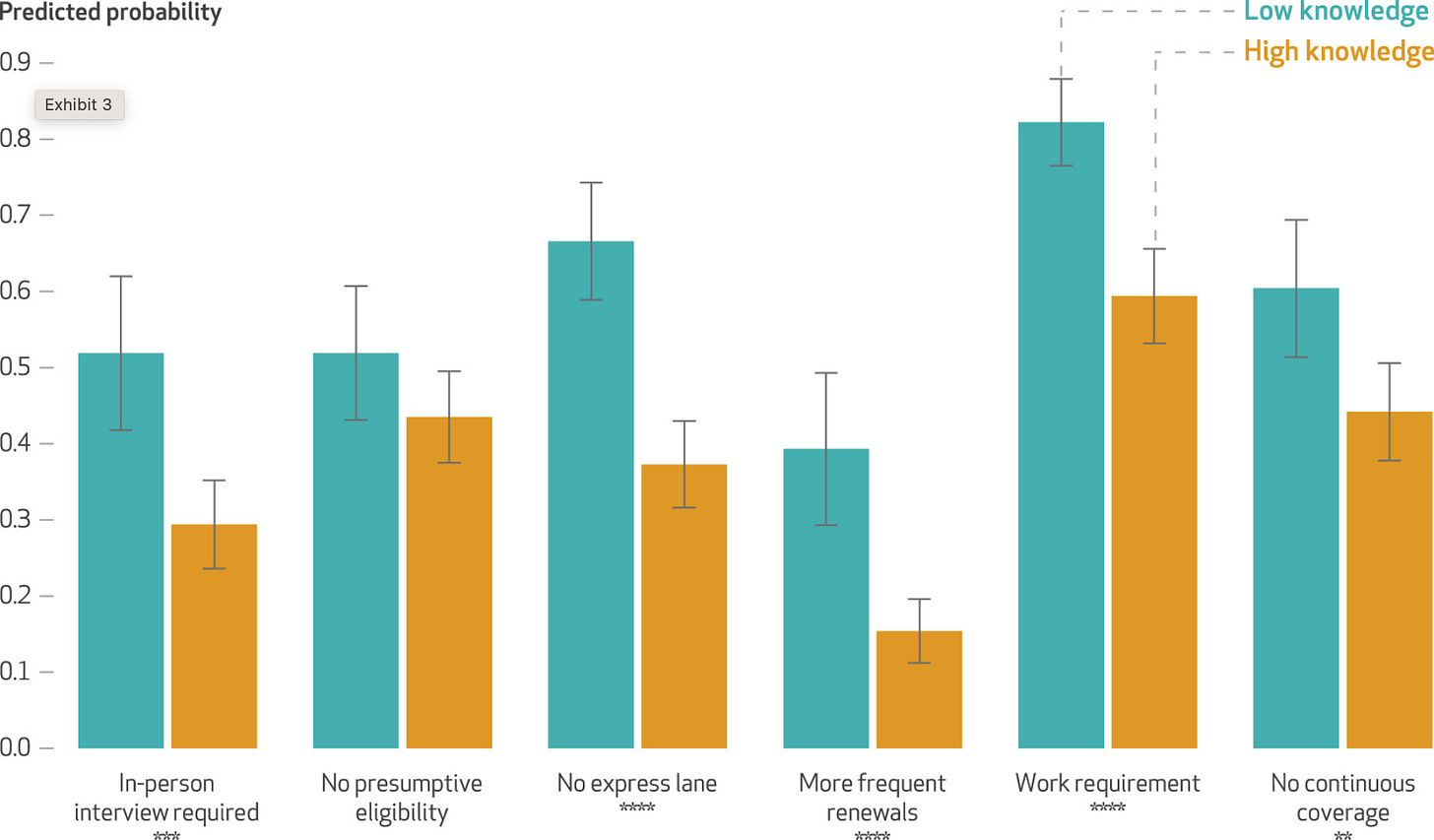

We also found that people who believed that burdens had a systemic impact by race were less tolerant of burdens.

Figure 3: Predicted probability of public support for administrative burdens in Medicaid, by level of knowledge of racial effects of administrative burdens, 2022–23

To simplify a bit, think of two people:

The person with more overtly racist beliefs will support burdens in social programs.

The person who perceives systemic racism will be more opposed to such burdens.

One conclusion of our research is that it is difficult to change people’s views of burdens by talking about race. The flip side of that is that the tenacity of the views about burdens in US social programs is inherently related to race. A different approach to alter people’s views might be to explain how burdensome administrative processes are, making it easier for them to understand the experience of those exposed to such burdens. This paper by Alexander Kustov and Michelangelo Landgrave shows that people tend to underestimate the complexity of immigration processes. Providing them with detail about how burdensome these processes are generates support for more liberal immigration policies.

For policymakers looking to reduce burdens, there is some positive news, with the results showing bipartisan support for less frequent enrollment renewals and allowing online application as an alternative to requiring in-person interviews. However, we also found support for work requirements, but with strong partisan differences, making them a natural battleground for fights about the welfare state in years to come. This finding helps explain why politicians have been willing to publicly campaign for work requirements, making them a central feature in the 2023 debt ceiling debate, despite evidence that work requirements do little to increase labor-force participation and lead to loss of coverage among eligible clients.

Racism in use of administrative discretion

An example of how street level discretion might increase burdens by racial and ethnic groups comes from research with Asmus Olsen and Jonas Høgh Kyhse-Andersen. We used an audit study to examine discrimination among Danish school officials. When those officials got requests from families with typically Danish names relative to those with typically Muslim names, they were more responsive to requests from the former, and more likely to ask more questions and be less friendly to the latter. There are examples of such bias in a US setting also, but also cases where street level bureaucrats do not display racial bias. In reviewing the evidence, it also seems that public employees were generally less prone to individual bias than private actors, presumably because public employees must respect stronger legal protections against discrimination.

Racialized burdens within organizations

Focusing on policy design or individual bureaucratic discrimination also felt limited to me, since it largely left the role of organizations out of the picture, even as I teach my students that organization history, culture and practices have dramatic effects on how public employees behave and the services the public experience. With Pam Herd and Victor Ray, we took Victor’s existing work on how organizations operate as racial structures that contribute to inequality, sometimes independent of bad actors or individual discretion, and applied it to the topic of administrative burdens.

Racialized burdens are the experience of learning, compliance and psychological costs that serve as inequality reproducing mechanisms. Racialized burdens neatly carry out the “how” in the production of racial inequality while concealing, or providing an alibi for, the “why.”

Racialized burdens are a type of administrative practice that normalize and reinforce patterns of racial inequality in public services, simultaneously reproducing disparate treatment while obscuring discrimination because bureaucratic actors are “just following the rules.”

We make three basic claims about racialized burdens:

1. Racialized burdens combine control of access to resources and ideas about racial groups in ways that typically disadvantage racially marginalized groups.

2. While still promising fair and equal treatment, racially disproportionate burdens can be laundered through facially neutral rules and via claims that burdens are necessary for unrelated reasons.

3. Racialized burdens emerge when more explicit forms of racial bias in policies or administrative practices become illegal, politically untenable or culturally unacceptable.

What this means in practice is not always easy to observe, which helps to explain their persistence. In our paper, we offer examples in the context of immigration, voting and social policies. Let me offer you another example. A paper in Public Administration Review by Joel Cuffey, Cara Newby and Sarah Smith examined how waivers from SNAP requirements, a means to reduce burdens, were sought and received by states. The researchers generally found fewer waivers in red states, consistent with an ideological explanation of administrative burdens, where Republicans are more supportive of burdens in social programs. They also found that counties with higher percentages of Black populations were less likely to receive a waiver, especially when located in Republican controlled states. This is a context where the rules, including the opportunity to seek waivers, are facially neutral even as they result in racially disparate outcomes, with the decision process and administrative practice shrouded in the black box of organizational processes.

How to identify and reduce racalized burdens

All of this may sound a bit hopeless. But my research has made me cautiously optimistic. I think there is room to reduce inequality by focusing on burdens. Here are some possible tools:

The use of the type of mystery shopper audit studies can verify that people do receive equal treatment, minimizing the use of bias by front-line officials.

Making services simpler for everyone by reducing burdens will also reduce disparities associated with burdens.

Offering outreach and help to groups traditionally marginalized by government.

Governments should collect data where there are cases where burdens are associated with disparate impacts, figure out why they exist, and eliminate them.

The last suggestion may sound a bit glib - identify problems and fix them! - but let me offer a real example, which is about how IRS audits have racially disparate impacts, how the Biden administration investigated this problem and committed to a real solution.

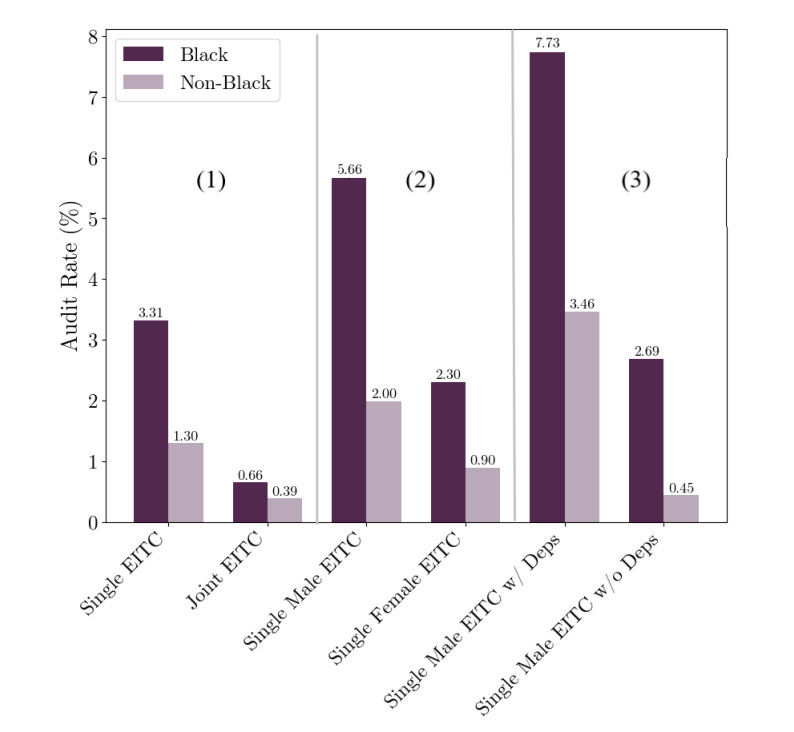

We've long known that the IRS disproportionately targets low income earners for audits. This strategy makes no sense in terms of chasing the biggest tax cheats or raising the most revenue. But political pressure (macro level factor) and the ease of such audits (meso level administrative processes) led the IRS to focus on Earned Income Tax Credit users. This might end up creating disparate racial risks of audits as more persons of color rely on the EITC.

But until recently we've not had evidence of whether IRS audits had racially disparate impacts. After Biden signed an executive order pledging to remove racialized burdens from public services, researchers at Stanford were given IRS data to explore this question. The IRS does not collect race data, so the researchers imputed race based on names and location. They found that, as expected, Black taxpayers were much more likely to be audited, primarily because of the EITC. The audit rates for Black EITC recipients could run two to three times the rate of other EITC recipients in equivalent situations.

The Treasury Department created working groups to explore racially disparate impacts and replicate the analysis. This sort of additional effort is the difference between research being used or not.

And now the IRS is revising its algorithms to try to minimize racially disparate impacts. The IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel promises to assess their progress in the future. The IRS is also using more resources to redirect audits toward those more likely to engage in large-scale cheating, and recently announced it has clawed back $122 million in unpaid taxes from 100 millionaires.

So basically, you have a mixture of high level leadership that makes a commitment (the Biden executive order), giving license for research on the problem, and then agency administrators taking that research seriously enough to make a good-faith effort to solve the problem. Which is sort of how a rational and responsive government is supposed to work. If such efforts get rewarded, expect more of them. If they are attacked or ignored, expect less.

I appreciate your explanation of the definitions, tools and an example of positive results in the area of race and administrative burdens. This is so important. One reason Amazon grew so quickly is its easy return policy and making drop off return locations accessible. Businesses understand administrative burdens, but unfortunately, don't improve racial burdens very well. The EITC is also unduly complicated to calculate because too many legislators believe that low-income people are gaming the system when, in reality, it's the wealthy who game the system.