How the higher education outrage sausage is made

I was exposed by Campus Reform and lived to tell the tale

I’d like to tell you a story. At one level, its a story about how a certain type of media content is made. This content is intended to show how out-of-touch and radical students and faculty are. The purpose is to delegitimate higher education, and intimidate certain voices. This content — lets call it campus craziness — has become ubiquitous in recent years.

I can tell this story because I was featured in one of these pieces, and so can give you an insiders perspective of how the content is produced and what it feels like to be featured. The bigger story is about the relatively recent creation of the broader media ecosystem that generates this content, leveraging the influence of billionaire conservative funders who see exerting greater control on campus as a key to broader political control.

The story starts with me waiting at airport picking up my in-laws. Their flight was late, so I started answering some emails on my phone. One query came from a Campus Reform reporter, about a tweet I had made about a research paper, asking if there was anything I wanted to add for a story they were going to run.

Now, if you know anything about Campus Reform, you might be thinking “I hope you didn’t respond.”

Reader, I responded to him.

I knew something about the organization, but was curious what would happen with a good faith answer to their questions. I asked what the angle of the piece would be. Reporter: “It's basically a round-up, or survey, of comments from various professors, some applauding the work and others taking issue with the implications of the results.”

So, I explained my tweet about a paper. The paper “When a Name Gives You Pause: Racialized Names and Time to Adoption in a County Dog Shelter” found that dogs in a shelter with names that were read as Black (e.g., Tyson) tended to be adopted more slowly than those with names that people viewed as White (e.g., Ben). The author explains the findings here.

Here is what I emailed to the reporter:

Here is why I think the study is interesting. There is a fairly substantial body of causal evidence that people discriminate based on names. These studies use experimental designs, so the causal effects can't be doubted. For example, they show that resumes with names that employers interpret as black are less likely to be called for an interview relative to more white sounding names. See, e.g. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1706255114 Another recent summary points to similar effects in rental housing, where equally qualified people are treated differently depending on their names. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3975770. There remains some question about why people respond to such names differently. Maybe they have had some prior negative experiences that provides some rationale for their responses. So I read the dog shelter study in that context. It takes away any such rationale: it's obviously silly to discriminate against dogs based on names, and so it points to an underlying bias that can't be accounted for by prior experience.

Of course, without this context, I realize it would be easy to caricature the paper as a "LOLZ these academics are studying dog discrimiantion." Which is why I tried to explain the context of a relatively sophisticated body of work in this area that needs to be accounted for to understand the contribution.

The actual headline of the resulting Campus Reform piece was not “LOLZ these academics are studying dog discrimination.” But it wasn’t much different.

The article highlighted academics who retweeted the paper, and their affiliation and research interests. Most of the faculty featured were faculty of color who study race. Anyway, lets see what happened to my detailed explanation.

Well, that Moynihan guy sure sounds like a blustery idiot who can’t defend his comments!

The piece comes with a sneer, but without any substantive critique. One defense of this mode of journalism is that it is merely quoting what academics say in public — what could be wrong with that? But this ignores the choices made in selecting, framing and (mis)representations of these faculty, the broader ecosystem that underlies it, and how this form of media was created. So lets get into those choices.

The explanation that I offered about why the academic paper was insightful — it wasn’t really about dogs, but how race is such a persistent factor in our lives that it alters our perceptions in even the most absurd circumstances — is ignored. While there is a disclaimer “Campus Reform reached out to all parties mentioned here” that is quite different from actually accurately representing the views of those parties. In other pieces, the reporter does represent the viewpoint of those he covers, but only when the subject of the stories are conservatives who are wronged on campus, who are then treated sympathetically and quoted extensively.

Because, of course, this is not a type of journalism that involves providing context, competing perspectives, or balance. It’s a hit-and-run job that plays on the prejudices of its reader. While Campus Reform claims it is interested in classroom speech, the vast majority of its coverage is of speech made by faculty in other settings, most obviously on social media. Such speech is generally regarded as protected for faculty in public institutions, since it is distinct from how the professor operates their classroom.

I don’t want to focus on the law school student who wrote the piece, who also has a gig at The College Fix, a similar outfit (I did reach out to him for comment, no response). His writing is relevant only to the degree it reflects the broader tendencies in this media. Of 15 pieces he has written for Campus Reform, six are about race, and five predominantly target faculty of color. These numbers are not representative of actual campus discussions, or the presence of faculty of color on campus. Instead, it reflects a set of choices, implicit or explicit, about what topics to target, and by extension, which professors to put under the spotlight. For example, the professor featured in the headline is not a national figure, and her tweet had been retweeted all of once. Why focus on her?

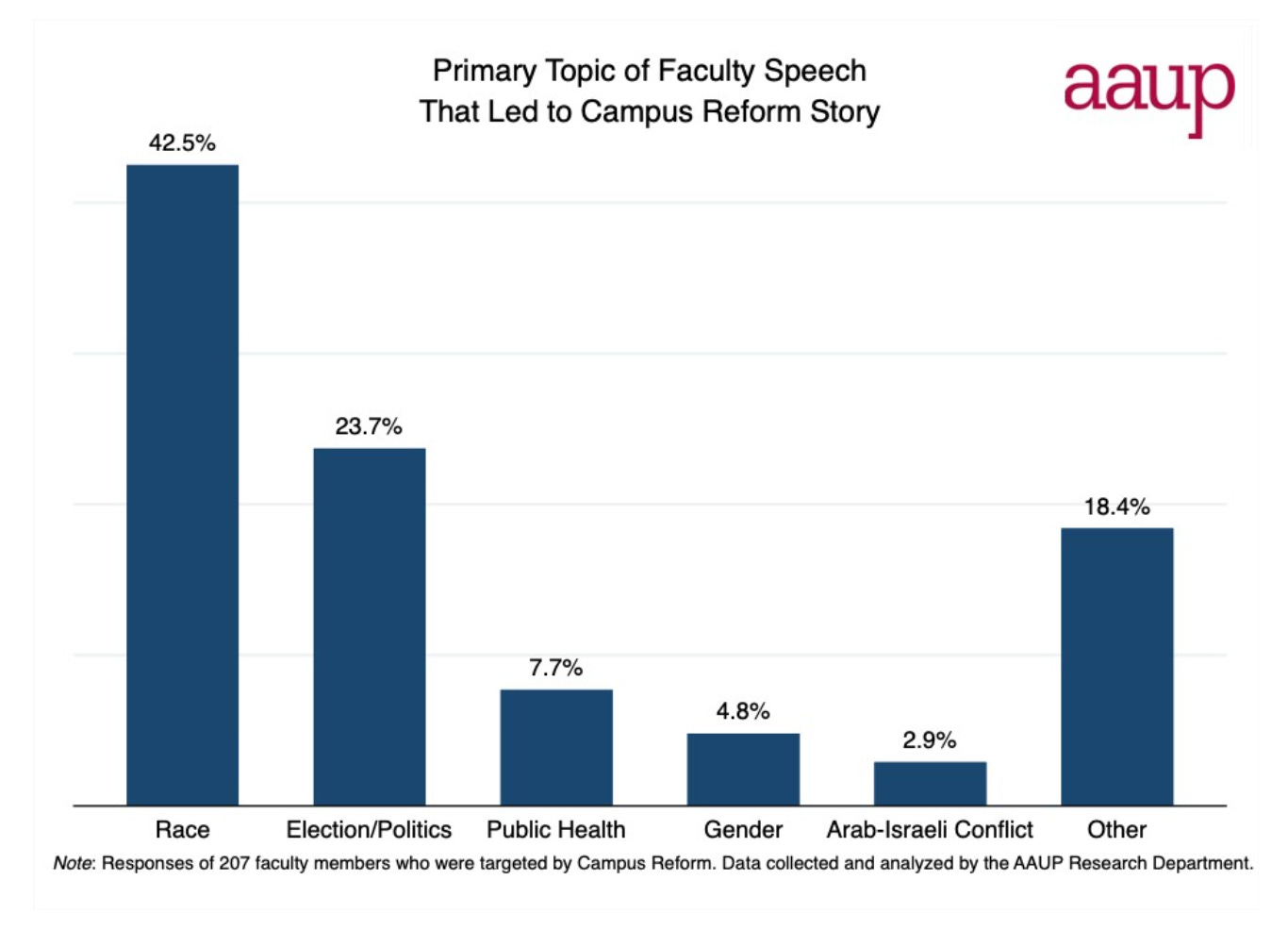

The focus on race extends to other Campus Reform reporters, suggesting it is an editorial choice. A survey of faculty who featured in Campus Reform pieces found that race was the topic that drew by far the most attention.

Blowback and chilling effects

I did not receive any particular blowback from being featured in the Campus Reform piece. But I was curious about the experience of the other faculty featured, and so contacted them. Some did not respond, or indicated they did not want to say anything else. Two did. One, who asked not to be named, said the following:

I didn’t know that an article had been published until I started to receive emails and odd mail. First, someone emailed me and my entire dissertation committee with racist overtones and berating me as a Black scholar. Second, someone subscribed me to ultra conservative magazines and had them sent to my department (gardens and guns, war memorabilia that included nazi based memorabilia, amongst others). While the first email was irritating, the magazines were cause for concern. It meant that someone was targeting me on campus. I didn’t return to campus for a week. I have slowed my twitter engagement since the article and have braced for blowback after any public engagement.

Another I spoke to pointed to the sense of fear that being in the article had created. Again, the chilling effect stood out:

I think the purpose of the piece is definitely to expose potential targets – even though it appears to be more of a list without incendiary comments or concrete call to action. I am definitely not feeling to good about it…

Other professors have found themselves subject to this hostility. Asha Rangappa, a Yale Professor and CNN contributor, describes the response after another Campus Reform story featured her tweet disputing Nikki Haley’s claim there was no racism in America:

I did not realize that there was a whole planned-out operation that works to promote disciplinary action or the firing of those they go after. As a CNN analyst, I’m used to hate mail, but these emails, some of which included satellite photos of my house, were unsettling. It was intimidation and it was unnerving, but learning that hundreds of other professors have been targeted was helpful. In both instances, the outrage died down in about a week. They were looking for a response to fuel the story, and when they didn’t get one, they moved on.

This experience is not unusual. A survey of faculty who had been featured in Campus Reform stories found the following:

Forty percent of respondents reported receiving threats of harm, including physical violence or death, following Campus Reform stories about them. Of these, 89 percent reported having received threats by email; 57 percent reported having received threats through direct messages on social media; 45 percent reported having received threats by phone; 13 percent reported having received threats in other ways, including by text message; and 11 percent reported having receiving threats through letters in the mail. An additional 10.7 percent of respondents reported that, even though they had not received threats of harm, they had received other types of unwanted, hateful, or harassing emails, direct messages, or mail.

Such threats had a predictable chilling effect.

There is no way that the publishers of Campus Reform are unaware that they are providing the raw materials for campaigns of intimidation. Campus Reform performs the neat trick of generating clicks and donations on the topic of cancel culture while actively fueling it. But while Campus Reform and similar organizations are an active and powerful player in undermining speech on campus, they are rarely the subject of investigations or think pieces about this topic. Why not?

Th higher ed outrage industry is a money-driven political project

I don’t want to suggest that people working in higher education are above criticism, that violations of speech don’t occur. Rather, the point is that the campus craziness content is carefully developed to generate this outrage. Traditional media has incentives to respond readers, and Lord knows, there is no shortage of pieces about woke students and faculty. As Bari Weiss explained: “Campus craziness sells”

But the type of media I am taking about generates an endless supply of campus craziness material in the hope of creating the demand. The best case scenario for such stories is that they go viral online, and get picked up by other parts of the conservative media food chain — they Daily Wire, the Daily Caller, the Federalist or Breitbart — and ultimately to legacy media with a national clout, such as Fox, the New York Post or the Wall Street Journal.

…with its own media

It is hard to overstate how much of this media ecosystem is a new feature of American society, and one that is financed or directed by the conservative billionaire class. Breitbart was created in 2007, the Federalist in 2013, the Daily Wire in 2015, the Daily Caller in 2010, the Washington Free Beacon in 2012. Campus Reform was created in 2009. Such entities do not just support each other; they rely disproportionately on the same set of funders: The Bradley Foundation, the DeVos family, the Mercers, Paul Singer, the Uihleins, and Kochs.

Some professions have their own specialist media to cover the new developments, with the audience generally being members of that profession, e.g. defense, tech or teaching. How many professions have media exclusively dedicated to writing one-sided hit jobs, underwritten by very wealthy ideological benefactors whose sole purpose is to delegitimate that profession?

The funding helps to connect campus conservatives with the traditional conservative establishment. Eleanor Bader in Sludge wrote an analysis of the origins and functioning of Campus Reform:

The group is a project of the Leadership Institute, a 41-year-old organization that was founded by New Right heavyweight Morton C. Blackwell. Blackwell is an ally of the late Paul Weyrich (co-founder of the right-wing Heritage Foundation, the American Legislative Exchange Council and the Free Congress Foundation); conservative political direct mail pioneer Richard Viguerie; and Edwin Feulner, president of the Heritage Foundation from 1972 to 2013 and from 2017 to 2018. In founding the Leadership Institute, Blackwell zeroed in on what he saw as the need to connect libertarian and conservative youth to one another, a need he first identified in the 1970s.

Blackwell’s vision is expansive and he has worked to foster organizational networking to link right-wing student organizations — and young minds — to the broader and more well-established conservative movement: The Heritage Foundation, The American Enterprise Institute, Americans for Prosperity, FreedomWorks, The Club for Growth, The Reason Foundation and the State Policy Network. But Blackwell has also gone further, noting that these connections would not matter unless money was ponied up to back the students’ work.

….dedicated to delegitimating higher education

Thus, one goal of the Leadership Institute and its funders is to change the conversation about campuses today. And it has been broadly successful. The creation of new media to critique campuses precedes a sharp decline in trust in higher education. This decline occurs among Republicans, especially Republicans who have never been to college, or have not been there for decades, and are relying on media accounts rather than first hand experience.

Have professors and students simply changed dramatically in a short space of time? Maybe some of this is happening, but the more plausible explanation is that a new form of media succeeded in increasing the salience and changing the coverage of the topic. Organizations like Campus Reform can feed Fox, who in turn shape the opinions of viewers, including Republican officials who announce they will use state power to fix this problem. Traditional media feel compelled to cover this big, new topic.

….and creating a network of conservative leaders

Beyond changing the narrative about campus today, these organizations are training leaders for tomorrow. This network promises to provide training, media skills, credentials and connections to willing college students. Again, from Bader:

In addition, upon graduation, many students working as Campus Reform “reporters” are fast-tracked to jobs with conservative lawmakers, think tanks or media outlets. At least six Campus Reform alumni now work for Fox News; other alums have landed positions at the Wall Street Journal, The Daily Caller, The Washington Examiner, CNN, The Georgia Law Review and National Review.

Some alum go directly into politics or political activism. James O’ Keefe worked as a Leadership Institute trainer before creating Project Veritas, until he was recently forced out because of his corrupt and abusive leadership style.

Henry Farrell notes the broad shift in the political economy of campus conservatism, which went from more tweedier debates about political philosophy to confrontations with the institutions they inhabit. This shift was not organic, but a reflection of the preferences, money and training provided by outside conservative groups that focus on college campuses like the Leadership Institute, Young America’s Foundation and Young Americans for Liberty.

These preferences shifted before the Great Awokening rather than arose in response to it, calculating that provocation, outrage and claims of censorship were key to energizing conservative forces on campus. Students followed the money and opportunities. Farrell quotes advice that a faculty advisor gave to conservative students seeking to get into politics (from the book, The Channels of Student Activism by Amy Binder and Jeffery Kidder).

Press is always good. You always want that …[the clubs] want to get it on YouTube. … So, you pick speakers that [are] creating something that will be explosive…. There’s a conflict, and [students are] behaving in that field of conflict, and that helps to get press. … You go to your donors and it’s very easy to show them, “We’re on CNN. Give us more money.” …[Students are] also looking down the road … at internships…. These are the [students] that are going to end up in politics. [ . . . ] And they know that by doing these types of events, especially if there’s some visibility [it’s] all the better for them.

The co-optation of traditional media

I had forgotten the Campus Reform piece until last week, when the New York Times featured an essay from someone they labeled as a “Princeton senior.” The essay bemoaned how liberal intolerance had turned free-thinkers into radical partisans. The billing left a few things out: Princeton senior had been involved in Republican political campaigns in Texas for Ted Cruz and Greg Abbott since his early teens, was President of the College Republicans, and publisher of a Princeton conservative news outlet. (Oddly enough, the crux of his argument is that moderates had become so radicalized on campus that they were now writing for his publication). And he is also listed as a campus correspondent for Campus Reform (though does not seem to have written anything for them).

The Princeton senior traversing Campus Reform and the New York Times is emblematic of the co-optation of traditional media by the new media intent on delegitimating campuses. Higher education is a big industry, and as with any big industry has its problems. The goal of the funders of Campus Reform has been to represents outlier events of a certain type as the norm. They have succeeded in persuading outlets like the Times to treat campus speech controversies as part of the campus craziness narrative (the intolerant left quashing free speech!) rather than another narrative (the moneyed right seeking to control campus speech).

As an example, when former Proud Boys leader Gavin McInnes leader was invited to Penn State, and his event canceled amidst violence, the national media failed to disclose that the event was organized by a student who was also a Campus Reform correspondent. That seemed like a crucial piece of information to place the event in context where the purpose of the event was not speech, but provocation, protest, violence, and the ensuing media coverage.

Such examples reflect an inability (or less charitably, an unwillingness) to understand how power is exercised over campuses, sometimes by the state, and sometimes by private actors, as is the case with the funders of Campus Reform. This is the broader, more complex and more consequential story about American higher education in recent years. To the extent it is told, it has been drowned out by campus craziness clickbait.

The early history of this massive level of subsidy goes back to the Dartmouth Review, where the proposition was pretty straightforward: write for the Review with the goal of outraging liberals and you'll not only get paid by outside funders but they'll look out for you afterwards. That proved a big success in terms of reliably recruiting students, training them in provocation, and connecting them up to media circuits that just kept growing over time. Once the media economy switched over to online publications that were semi-automated or bot-driven, this strategy also provided a pretty reliable source of low-paid interns who did the same thing for right-wing outrage farms as they did for Buzzfeed, etc.--constant scanning for anything from elite selective institutions that could be blown up into short-lived feeding frenzies. Back when those interns were learning their craft, a favorite thing was to read over the MLA program and course catalogs looking for titles that could be called out as silly radical nonsense. The Weekly Standard, which essentially was operating like the College Fix a while back, once picked out a course I taught called The Whole Enchilada, thinking it was about Mexican food, when in fact it was a pretty serious and heavy-reading-load exploration of "universal history" as a concept, with readings that included Genesis, Enlightenment theorists, Oswald Spengler, "big history", etc., so that was a rare case where the cherry-picking was so obviously missing the mark that even a few conservative academic bloggers back in those early days scolded them. We're long past that moment--no one cares whether any of it is remotely accurate any more.