The campaign that removed the President of Harvard was about DEI, not plagiarism

Is there a difference between covering the culture wars and participating in them?

Here is what happened. Elise Stefanik, a member of Congress who has trafficked in Great Replacement white nationalist theory, called three female leaders of universities to Congress alleging they were enabling anti-semitism. She called for all of them to resign. The President of Penn did. Two universities stood by their leaders. Other far-right figures pursued Claudine Gay, the President of Harvard, accusing her of plagiarism. But really the goal is to remove her as a symbol of diversity, equity and inclusion. And too many in the media have been active participants in this campaign. On January 2, Gay resigned.

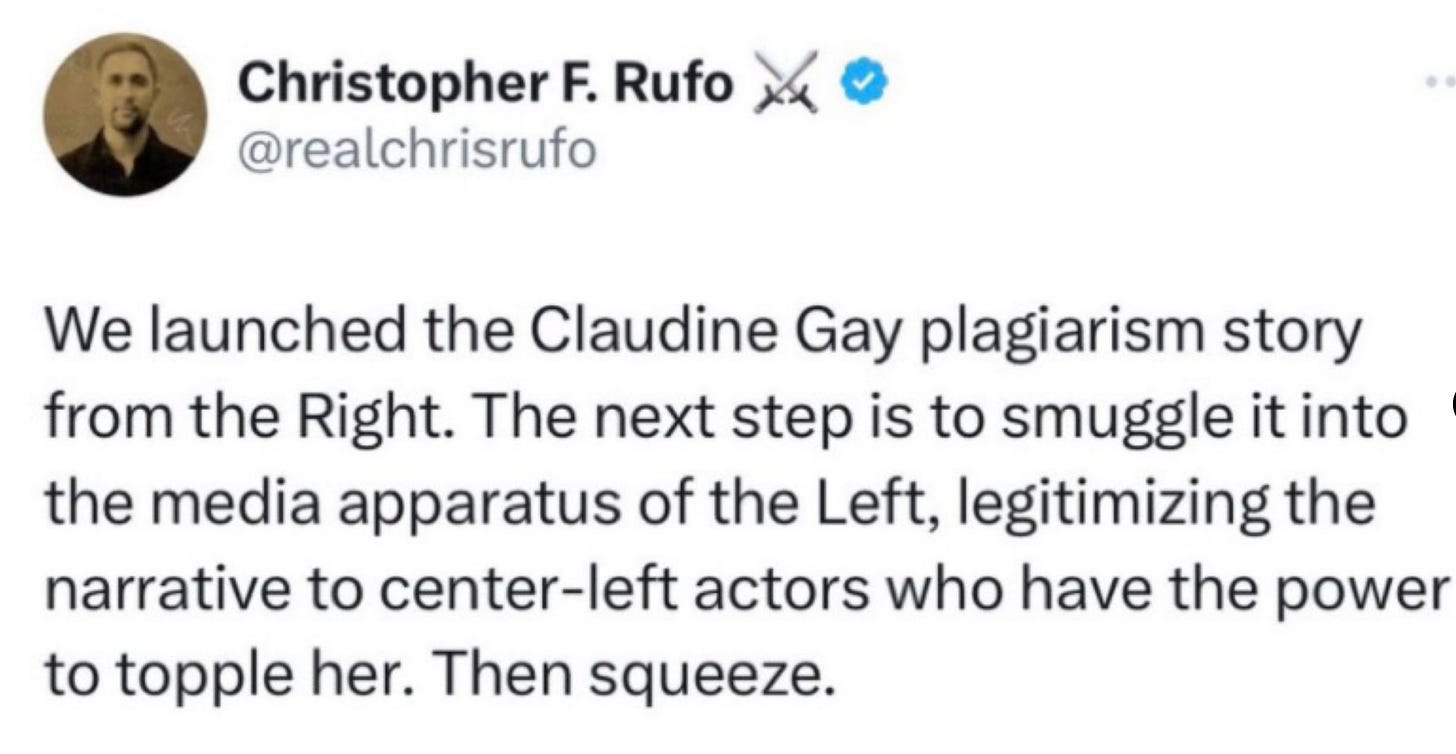

What does plagiarism have to do with anti-semitism? Nothing. But the goal was to remove Gay, the first Black president of Harvard. The campaign was open. To understand this, it makes sense to start with Christopher Rufo. Rufo is the most effective culture war strategist in attacking public education generally, and what he argues is the excessively liberal nature of higher education, in particular. His main tactic, repeated again and again, is to come up with a negative brand, and then demand that powerful actors denounce that negative brand, and do something about it that erases a broader set of liberal values. He has done this with discussions of race (labeling it Critical Race Theory) and gender (accusing those allowing discussion of gender in schools to be “groomers”) in classrooms. He saw the opportunity to leverage anti-semitic student protests as part of his broader attack on higher education.

This succeeded up to a point. Elise Stefanik, a Harvard alum who was removed from the advisory board of Harvard’s Institute of Politics for lying about and voting against the outcome of the 2020 election, held a hearing with the leaders of MIT, Harvard and Penn, following Rufo’s strategy. The leaders performed dismally (and Gay subsequently apologized), but I’ve not seen anyone offer a persuasive claim that the statements they gave, under oath, were inaccurate. On many campuses, what might be considered hate speech is allowed. Indeed, what the right has told campuses over the last decade is that such speech is necessary. If you opine, for example, that some racial groups are genetically or culturally inferior and have a lower IQ, you must be heard. If you claim that people’s beliefs about their gender identity is a form of mental illness that must be eradicated, you can rely on campuses to provide space and security for your campus tour. Maybe this should be different, but again, the dominant message from the right and mainstream media has consistently been that universities were too quick to regulate speech on campus.

Stefanik’s hearing saw the leader of Penn, after the urging of some donors, resign. But Harvard announced its support for Gay. Then Rufo took a different tack, which was to push a campaign against Claudine Gay for instances of plagiarism.

The campaign relied on analyses by Christopher Brunet, a blogger who lost his job from the conservative Daily Caller after he previously made false accusations of another Harvard professor of fabricating data in his research about race. He specializes in targeting academics who work on topics related to race and gender. He therefore is neither a neutral nor especially reliable source, but he served Rufo’s purpose, and they jointly published the plagiarism accusations.

For this campaign to work, they needed mainstream media to support them. And the media obliged. All in all, it has been a very successful couple of weeks for bad-faith attacks on higher education. In just 10 days, the New York Times published 13 pieces about the President of one university in the aftermath of both the hearings and the plagiarism allegations.

Is that a lot? To provide a comparison, we would need a benchmark of a university president accused of academic misconduct at a very prestigious institution. As it turns out, Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne faced more serious accusations of academic misconduct involving data manipulation. A formal investigation was announced in November of 2022, and he was forced to resign in July of 2023.

So, how many articles did the Times write about the topic prior to his resignation? Zero.

Let’s take another example, specifically about plagiarism. In 2017, when he was nominated for the position of Supreme Court Justice, Neil Gorsuch faced accusations of plagiarism. Significant passages of text were borrowed word-for-word from others, sometimes without citation.

How many stories did the New York Times feature about Gorsuch’s plagiarism? Zero.

The Washington Post covered the revelations twice. One framed it as “Democrats in Hail Mary mode” over a “pretty minor offense” and the other, by Jonathan Adler, denounced as an example of “the politics of personal destruction.” It turns out you can cover politically motivated efforts that use plagiarism as a tool to smear people, and even denounce such campaigns!

Both Post writers noted that the plagiarism was real, but an example of sloppiness in using descriptive factual text rather than stealing big ideas, as did some scholars Gorsuch plagiarized. But that is also the case for Gay. Maybe you think Gay’s position as a college President makes her case different. But being a Supreme Court Justice is an important position, where the legitimacy of the institution and those who work there matters a lot. The argument for Gorsuch’s nomination rested partly on his intellectual brilliance, which was derived from his writings.

Regardless of where you stand on the severity of plagiarism, it is worth asking why Gorsuch got a free pass while Gay was hounded out of office. Why, in one case, the scant media coverage tole readers that such accusations of plagiarism were not that big a deal, and should be ignored, while in the other case they framed them as a legitimate issue that put her position in question? For those who want to make the argument that plagiarism is plagiarism, and that even if Gay’s attackers were acting in bad faith, her position was untenable, they fail to account for these extraordinary differences in coverage. If bad faith campaigns are by their definition not even-handed in who they go after, why does the media participate in some of those campaigns and not others?

I focus on the New York Times not because it is unusual, but because it is the standard bearer for the news. It wasn’t just the Times. Other national media treated the topic as national news. Something more important than almost everything else. Something that deserves your attention.

In doing so, the media fed Rufo’s feeding frenzy. The story was newsworthy because they said it was newsworthy. It justifies the dubious idea that Congress, which has another government shutdown pending, should spend its time investigating the research record of one university leader. Which will then generate another round of stories.

Rufo’s campaign worked. He announced it publicly, explained its motivations, the media played their assigned role, and Rufo took the credit. You might ask how this can happen, but the better question is why it keeps happening.

Gay was permanently damaged as a leader. What happens when the most powerful media outlets in the world, ask, day in and day out, if you should be removed from your job? At some point key stakeholders, even supportive ones, start asking the same question. You have become a distraction. Time to move on for the good of the institution. We need a less contentious leader. The controversy becomes sufficient reason for the leader to go, even if the underlying causes are trivial.

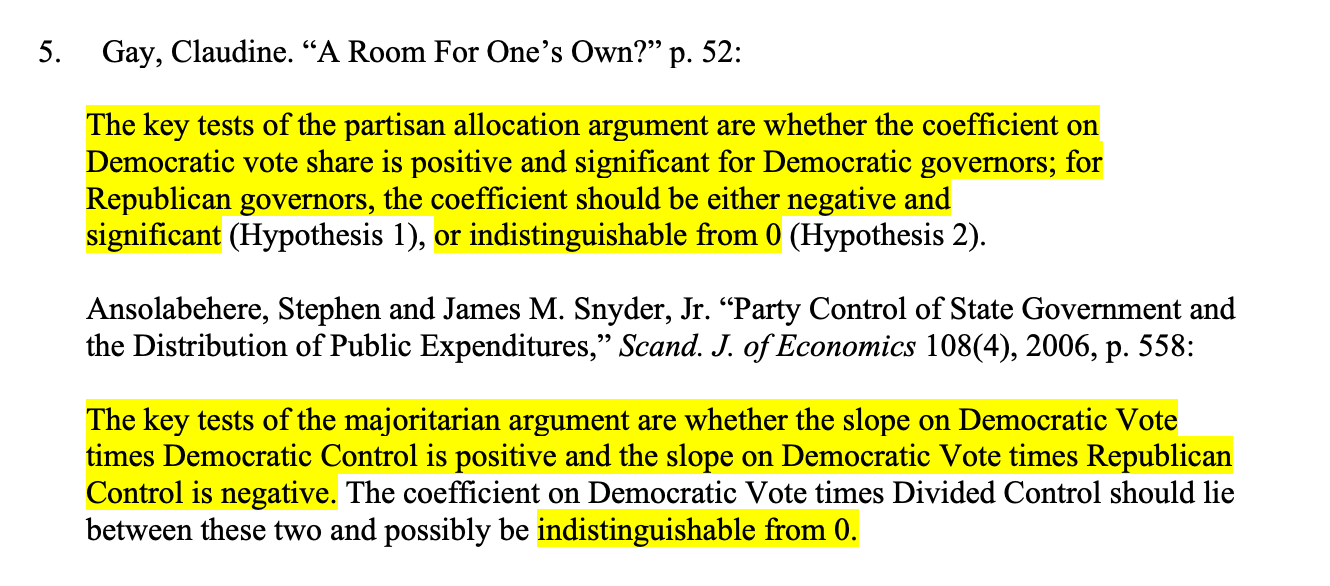

As for the accusations of plagiarism: There are degrees of wrongdoing here. At its core, policies against plagiarism are intended to prevent against academic fraud, that someone is stealing the analytical work or core ideas of another scholar, and passing them off as their own. That is not the accusation against Gay. Instead, there are instances where she took a sentence or even multiple sentences and only slightly paraphrased the words and did not include a citation, or sometimes included a citation but not quotation marks. Here is one of the examples that critics have highlighted.

This is not good. It shows, at best, sloppiness, and at worst, an willingness an indifference to giving credit to other authors. But it is also very different from the claim that Dr. Gay’s work is really the work of others. The passages are not central to the intellectual contribution of her work. It is certainly newsworthy, but is it really national news demanding story after story? But lets be honest, the campaign is not really about her academic record. Folks who participate in Prager U videos are not stickers for academic integrity.

There is a difference between covering and participating in a culture war story

Gay was attacked because she is seen by the right as undeserving of the job. A diversity hire.1 Too woke. Taking the university in the wrong direction. In particular, Gay is under attack because she has been perceived as too supportive of DEI as a university Dean.

Gays removal is as much a victory for the New York Times, Jake Tapper and others in the media as it will be to Chris Rufo. A testimony to their power, but also to their incredulity and willingness to serve the goals of others.

The background here is that there is a campaign to remove both the formal offices and vestiges of diversity, equity and inclusion on American campuses. It is led by Rufo at the Manhattan Institute, who has produced model legislation for states to adopt. (The Manhattan Institute also employs John McWhorter, the New York Times columnist who is calling for Gay’s resignation). The Times even gave Rufo a column calling for the removal of DEI. Such offices existed before the murder of George Floyd, but in its aftermath, have been attacked for being too powerful. Firing Gay will be the biggest scalp yet for the anti-DEI forces, the clearest warning signal to universities to stop pushing such goals.

If you think I am exaggerating about the role DEI plays here, lets consult Rufo again. He is explicit that DEI is a reason for targeting Gay (and not the white President of MIT, for example), in conflating DEI and anti-semitism, and claiming credit for the success of his anti-DEI mission.

He even wrote an article about this!

I would argue that the concerted attack of DEI on campuses is perhaps a more newsworthy story than Gay’s plagiarism. For example, in the same time frame that the Times wrote a dozen stories about Gay, the Assembly Leader in Wisconsin, Robin Vos, stepped in to prevent pay raises for all employees at the University of Wisconsin system unless DEI offices were cut. And the Governor of Oklahoma signed an executive order removing funding from DEI offices in the university system. Neither event was covered in the Times. Legislation banning DEI has become law in other states, including Florida, Texas, North Dakota, Tennessee, and North Carolina. To the degree they are covered, such events are not treated as a critical story demanding your attention in the same way that Gay’s leadership at Harvard has been. Actual policy changes related to race on larger campuses matter less than whatever is happening at Harvard.

It is entirely feasible to not treat the bad-faith framings of events by the far right as legitimate news. It’s a choice. If you are concerned about the integrity of higher ed, there are more pressing examples. A recent AAUP report on censorship and the imposition of political control in Florida, for example, is vastly more important and deserves more attention. As Paul Krugman points out, in the only piece in the Times that covered the report as best as I can tell, 430,000 students are in higher education in Florida, compared to 7,000 undergrads in Harvard. In New College, where the experiment has gone furthest, Chris Rufo and other political appointees have overseen a pattern of cronyism, censorship and incompetence. This is how they want to transform higher education.

The obsessive culture war coverage of the Ivies hurts other institutions

As a reminder, just 0.4% of undergraduates to to all Ivy League institutions. Sure, they are important in terms of their cultural weight, but the obsession with them is unhealthy, and has the effect of misrepresenting what is happening on college campuses. I truly don’t understand why this is the case. One reason I’ve seen suggested is that elite media, like the Times, is disproportionately stacked with Ivy grads.

Another problem in the Times is that writers about higher education aren’t actual experts on higher education. In many cases, they treat higher education purely from a culture war perspective, building on narratives of woke students and besieged conservatives. For example, Anemona Hartocollis, the Harvard alum reporter who is writing obsessively about Gay wrote warm personal profiles of a Princeton professor disciplined for having sex with students and then lying about it and his wife (a former student). She also wrote sympathetically about Ilya Shapiro, the conservative who resigned from Georgetown after being investigated for denigrating a Supreme Court nominee as a “lesser Black women.” The reporter later treated Shapiro as an expert on Black history, despite the fact he is now working with Rufo at the Manhattan Institute in their anti-DEI campaign.

She continued to post about alleged plagiarism, even after Gay resigned, relying on an anonymous complaint, published by the Washington Free Beacon, a right wing media outlet.

One alleged victim of the plagiarism, David Canon, is a co-author of mine. He told the Beacon: “I am not at all concerned about the passages. This isn't even close to an example of academic plagiarism.” Canon’s response was not included in the Time’s coverage. The proposed examples of plagiarism (below), including technical descriptions of variables, are so broad that they would snag an extraordinary number of faculty. The Times did not weigh in on the validity of the claims.

In short, an anonymous complainant made some claims, tipped off a sympathetic reporter (who Rufo identified as a participant in the campaign to remove Gay) in a right wing outlet, and Times reporters treated all of this as national news. Concern about due process for academics facing unfair accusations, a preoccupation of Hartocollis’ prior coverage, was forgotten. She was eventually interviewed in the Times about covering the topic. Given the degree of criticism the Times took about its coverage, this offered an opportunity for self-reflection, or at least addressing those criticisms. The opportunity was left untaken. The interview was a series of softballs that avoided any implication that the Times had been driving the narrative. Still, the answers managed to be revealing. When asked to consider what the “big-picture questions” that arose from the story, Hartocollis responded: “What do we expect of a Harvard president, the leader of probably the most prestigious university in the country? Did race factor into her selection and how much should it for any academic or administrative position?” The question of whether race mattered to Gay’s loss of the position was left unasked, as was the role of the anti-DEI and right-wing forces whose agenda was being served by the Times.

It could also be that many of those writing on this topic agree with Rufo’s perspective, and think the Ivies they focus on have become too woke. Ultimately, the Ivies will get along fine. They will develop an equilibrium between their ideals and their donors. I worry more about what happens elsewhere. The biggest story about higher education over the last decade has been increased politicization, not wokeness. The biggest threats to speech are coming from people who write the laws and set the budgets, not from students.

Laws eliminating DEI offices come on top of laws restricting speech in classrooms about race or gender. University trustees in public institutions are increasingly political appointees determined to impose right wing values. The higher education equivalent of gerrymandering is to rewrite leadership hiring processes to remove the voice of faculty and students, who have less and less say in determining who leads their institution. What happens at the Ivies offers political justification for governments in red states to continue their ideological push to remake higher ed.

It will get worse

What we are seeing happening in red states will continue. At this point the right has decided that higher education is the enemy, and it will continue to delegitimize it to justify illiberal tactics of control. They have their own media to serve this purpose, but are relying on the traditional media to amplify the delegitimization, and ignore, or fail to connect, the resulting illiberal control.

It will get worse under a Trump Presidency. Trump signed an anti-CRT executive order as President. If he returns, expect a more agressive campaign to leverage federal power over higher education, threatening federal funding or college accreditation. The net effect will be to erode the autonomy of campuses, and impose genuine threats to free speech, at a time when we will need independent voices in society more than ever.

The removal of Gay will also embolden activists like Rufo, whose campaign succeeded. Upon news of the resignation, Rufo tweeted “scapled” (he meant “scalped”) before reiterating that the campaign was about DEI. Rufo took a victory lap, taking credit for co-opting a lot mainstream media resources to serve in a campaign that led to the first Black leader of Harvard holding the shortest tenure in the job.

I worry that neither the media nor universities are equipped to deal with politically motivated accusations of academic misconduct. Such accusations can be made by anyone, even anonymously, and put the academic under a cloud while a university or journal investigates. Since Gay’s resignation, Chris Rufo announced he was creating a fund to investigate academics for plagiarism. Ian Bogost tested out how this might work, by investigating his own scholarly work. What he found is that for $300 he could pay an online website that generated a result that implied he had engaged in significant plagiarism, while it took hours of manual effort to verify that he hadn’t. Most members of the public are unlikely to understand nuances such as the difference between sloppiness and clear intent, or how standards of data replication or analysis have evolved over time. If the researchers are cleared, the accusers will argue that the institutions themselves are corrupt, and “accused plagiarist” is not a smear that ever permanently fades. It is, therefore, an accusation that is cheap and easy to make, and will generate some sort of effect as long as a motivated audience treats the accusations as credible.

Will be any soul-searching at the Times and elsewhere about their role in pushing Gay from office? Determined to establish they were not woke, they pushed a story of academic malfeasance while ignoring other, more serious, accusations of leaders in similar positions. This will not stop the right wing claims of some secret alliance between media and academia, because the claims themselves have proven to offer agenda-setting power even if untrue.

Strategies that work will be used until they stop working. Appeasing such campaigns will result in more of them, while gaining the targeted universities little in exchange. Expect more attacks on faculty, leaders and programs from the right. To succeed, such campaigns will depend on media and academic institutions treating them as good faith in their intentions, as they did with Gay. Universities will be more reluctant to promote leaders of color on campus, or DEI initiatives. Faculty will be more reluctant to speak out. The message about who really runs the university, and who they are responsive to, could not be clearer.

Alvin Tillery has written the best thing I’ve seen about Gay’s academic record. She did not publish a lot, but her record was not that different than other Harvard Presidents. She published in the top three political science journals with solo-authored pieces. Anyone who knows the field knows that this is an extraordinary achievement, and her work is widely respected. Her research productivity slows later in her career, but this is entirely typical for academics who are moving into academic leadership roles, which are all-consuming.

This deserves to be published in the NYT. You might clean it up and send it there, either as a letter to the editor or as a guest columnist. Please! Thank you! Excellent and informative.

"The higher education equivalent of gerrymandering is to rewrite leadership hiring processes to remove the voice of faculty and students, who have less and less say in determining who leads their institution." Absolutely true. At most universities that have DEI officers, committees, etc., they meet a lot, they talk a lot, they give campus-wide presentations but, at the end of the day, they don't move the needle. It takes a lot of this before society sees results and cutting it down at this stage negatively affects the future.