Will the IRS finally create a good free tax reporting process or will the tax preparation industry win again?

A crucial test of whether the American political system can deliver administrative capacity to serve the public

Americans are taxed twice. First, there is the money that they owe. Second, is the time tax of an unnecessarily onerous and confusing tax reporting system. The burdens involved are great enough that many of us pay others to deal with them.

The good news: the US government can take advantage of technology and administrative data to make one of the frequent interactions the public has with the public sector less onerous and expensive. It even has a policy window to do so thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

The bad news: the same forces that arrayed to stop this from happening for the past two decades are ready to strike again, using the same tools — money and fear — that will leave us with the same outcomes: a tax reporting market without a functional public option, resulting in lost time and money for taxpayers.

A moment of opportunity

The current flashpoint centers on the IRA earmarking $15 million to investigate the feasibility of a free federal direct tax filing service, with a report due to Congress in May. This comes more than 20 years after the Bush administration first considered free electronic filing, so if we are making progress, it is at a glacial pace.

Technically, the US offers a version of free filing, but only about 2-3% of people use it. The product is not very good, as I wrote last year, because it was created in “partnership” with the tax preparation industry, who strangled the public option, while marketing their own “free” option that relied on dark patterns to get people to pay for a product many did not want.

Meanwhile other countries are providing some version of free direct filing of taxes. The US has a more complex tax system than most, but researchers estimate that between 41-48% of returns could be completed accurately by pre-populating data that the IRS already has. For the tens of millions of people who fall into that category, paying taxes would become substantially easier. Others could still choose prepare their own taxes, but benefit from access to IRS data.

Dylan Matthews of Vox did a conservative back-of-the-envelope calculations of how much pre-filled forms could reduce the time tax. Assuming pre-population cuts the filing time in half for 62 million filers, this would save the equivalent of 32,000 years of life.1 That’s a lot!

Public direct filing of taxes seems like a no-brainer, s a great example of shifting unnecessary administrative burdens onto the state. So why is it being contested?

The short answer is a mixture of rent-seeking and political ideology. On the one side, you have the companies who make a lot of money from the status quo, and are spending some of that money to defend it. They are aligned with conservatives who don’t want the tax system to be functional. On the other side are the rest of us, who end up footing the bill in one way or another.

We are at a crucial moment when those opposed to a better tax reporting system are arraying their forces once more. Will they succeed? The question gets at the heart of whether we can make meaningful investments in government capacity in a populist era, or in an policy domain where private interests profit from blocking such investments.

So what is happening?

The private tax industry steps up lobbying

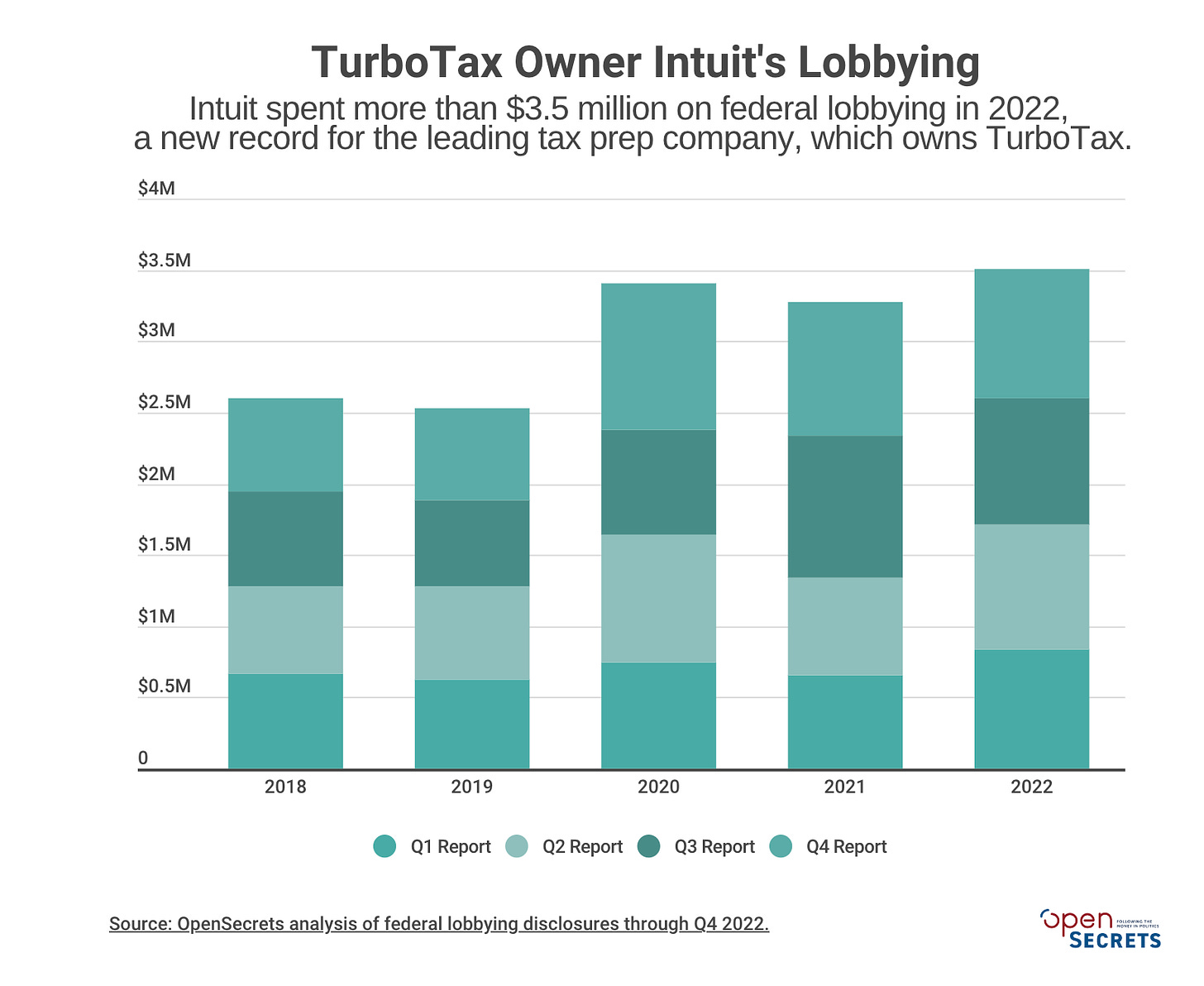

Intuit, the maker of TurboTax, is spending more than ever on lobbying, topping out at $3.5 million in federal spending in 2022. This is just the latest stage in a multi-decade campaign to stop the federal government — and state governments — from making tax reporting easier.2

Influence comes not just from direct support to legislators, but to well-connected lobbyists, including former Congressional staffers from both parties.

There is no equivalent public coalition to fight back. No millions of dollars. No lobbyists who used to work in key offices. No influential party bundlers. IRS staff can make the case for why direct filing with the IRS is in the public interest, but it does not have a campaign budget, and is unlikely to respond to reporter questions.

It’s a classic story of concentrated interests using their power to protect themselves at the expense of everyone else. Political scientists argue that such narrow, highly-motivated groups tend to defeat the broader public interest. Such victories are more likely in a political system that allows rent-seekers to make cash contributions to elected officials.

Rounding up the usual ideological suspects

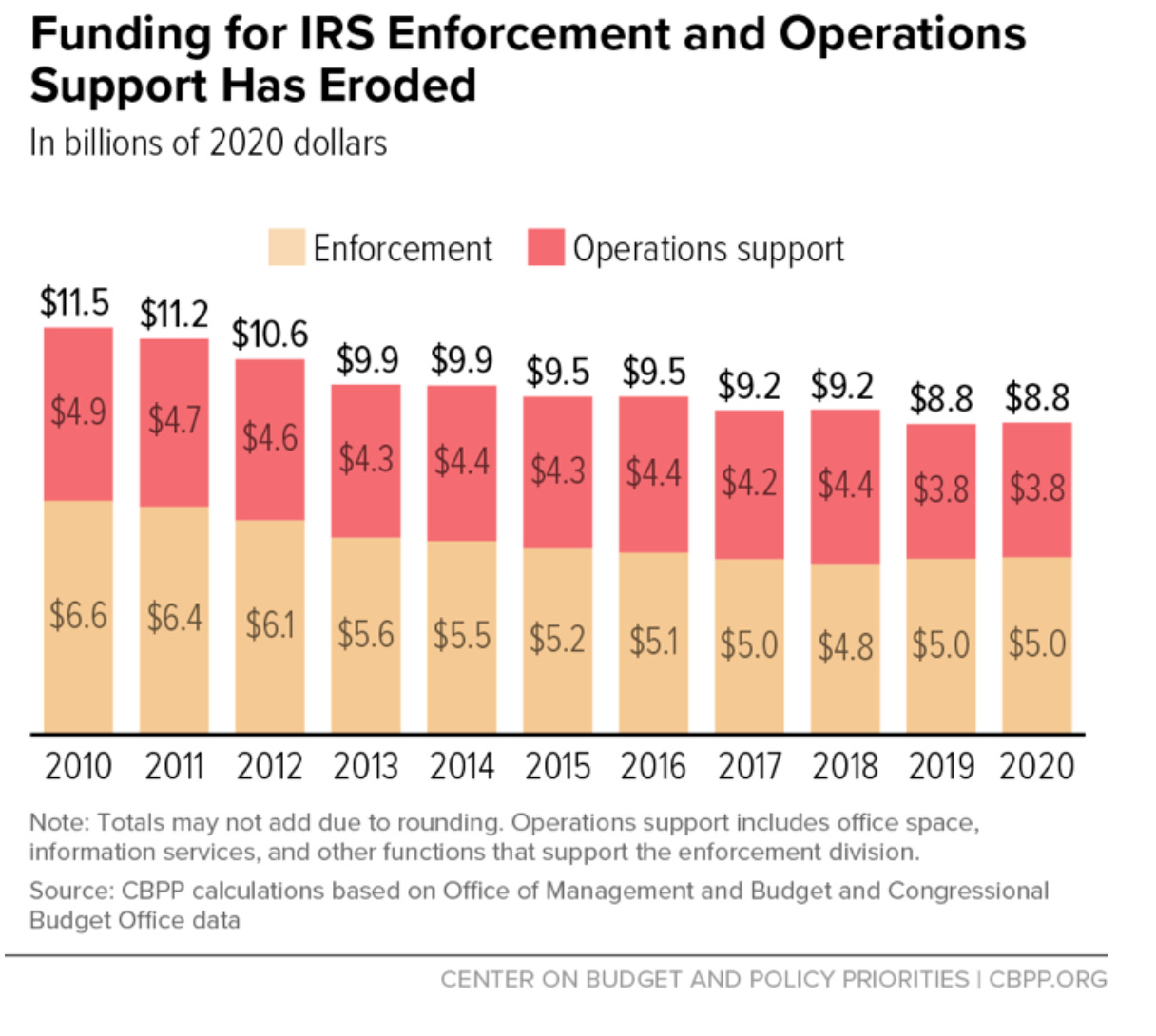

A part of the American right that so abhors taxes that it views the competent collection of revenue as something to oppose no less than the taxes themselves. They were dealt a rare defeat with an overdue funding boost for the IRS that came with the IRA.

Their response was not a debate about administrative capacity: it was to relentlessly push the lie that the IRA would fund 87,000 armed agents who were coming after you. But reality is starting to catch up with the lie. Half of the new IRS money spent thus far is going on hiring new staff to improve customer service. This is paying off:

The IRS had, at the end of February, 2 million unprocessed individual returns compared to 24 million a year earlier.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen says that 80-90% of customer service calls are getting through, compared to 13% in 2022.

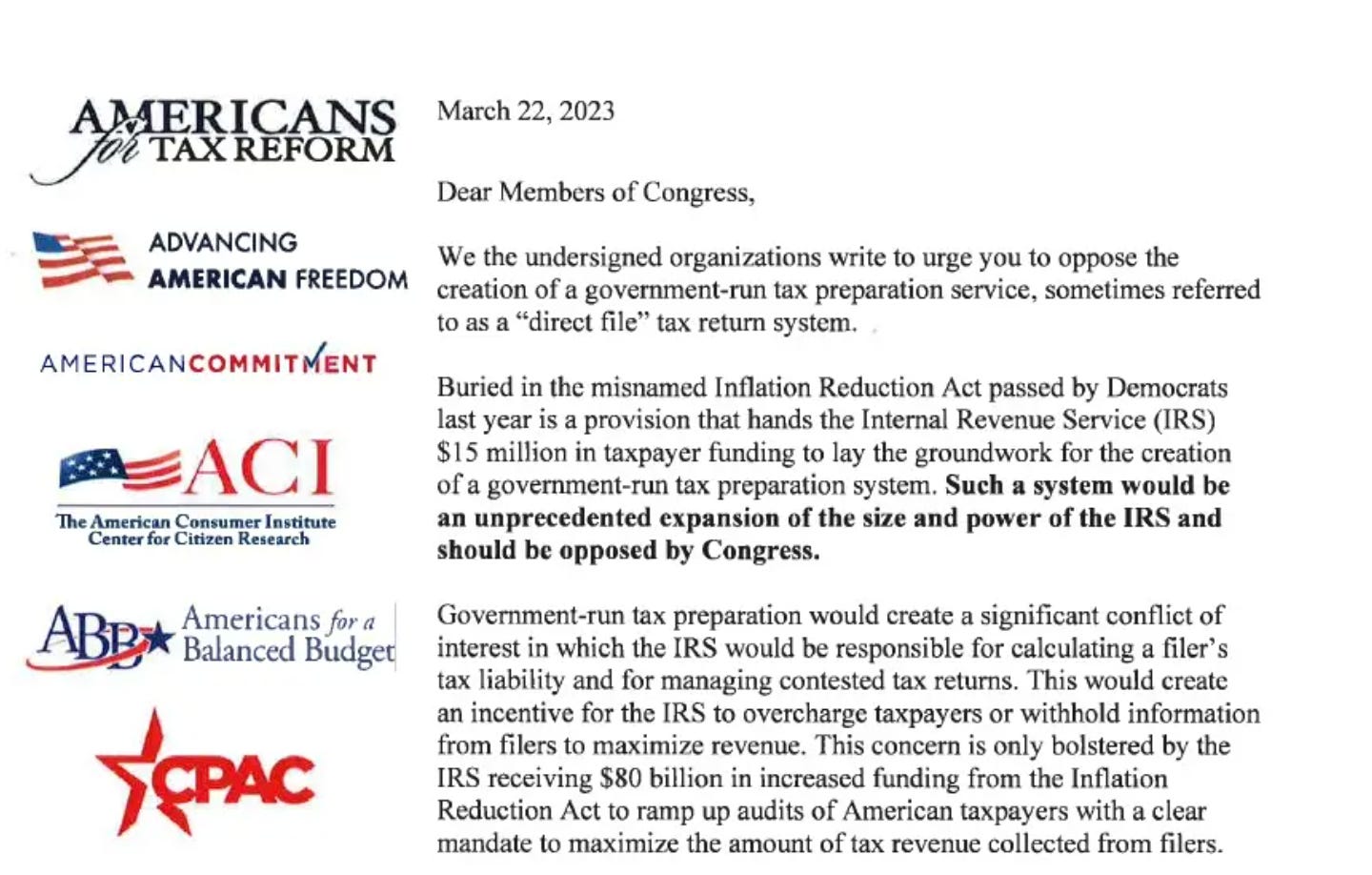

Nonetheless, a coalition of anti-tax groups have been lobbying Congress against the plan to further improve customer service with a direct filing system. Some, such as Grover Norquist, have been opposing a functional tax system for decades. This benefits some taxpayers, to be sure, but it is predominantly the very wealthy who don’t want to pay taxes and have the resources to avoid paying their share. A broken system does little to help regular salaried employees who don’t have the capacity to exploit loopholes but would prefer to spend less time preparing their taxes.

The anti-tax groups roll out out the same tired arguments they have since versions of direct file were first proposed, chiefly that there is a conflict of interest between the IRS collecting taxes and estimating tax liability. Not coincidentally, Intuit makes exactly the same claim. “Unquestionably, a government-run tax preparation system that makes the tax collector the investigator, auditor, enforcer, and now also the preparer, is a conflict of interest” says Intuit CEO, Susan Goodarzi.

This claim falls apart upon any sort of inspection. The IRS would not provide tax preparation advice: it would merely make available to taxpayers the data that individuals or employers have already provided to them, and apply it consistent with tax law. Taxpayers would be free to ignore this data and submit tax returns via some other method.

The “conflict of interest” claim is especially difficult to swallow coming from Intuit, who used deceptive tactics to solicit payments for what was often advertised as a free tax returns. Intuit paid $141 million in restitution to 4.4 million taxpayers, but Democratic lawmakers pushing for direct filing allege that the scale of the deception runs into billions of dollars.

The IRS has an incentive to get you to pay your taxes, but it does not have a profit incentive to rip you off. Indeed, it has strong political incentives not to abuse taxpayers, since horror stories of IRS agents lead to agressive oversight. Congress more closely monitors how the IRS treats taxpayers relative to the private tax industry. See, such for example, the excellent National Taxpayer’s Advocate as an example of institutionalized accountability to the public embedded within the IRS, or less positively, the efforts to gin up cycles of outrage around alleged targeting of political groups. And unlike the private tax industry, the IRS cannot hand money to legislators to look the other way when it screws up.

Discrediting the experts

Consistent with the guidance of the IRA, the IRS invited the New America Foundation, a progressive think tank, to explore the feasibility of a new system. GOP members of the House Ways and Means are opposing this step before the report is even delivered, arguing that the experts selected are discredited because they are too left-leaning and have already studied the topic.

They offered the following as an example of a disqualifying quote from Ariel Jurow-Kleiman, a tax professor working with New America: “the IRS should adopt the most expansive version of the program, one that includes the maximum amount of taxpayer information and requires the least amount of taxpayer input for each individual taxpayer.”

As smoking guns go, this one falls a little short. Thinking that it is damning to call for reducing the burdens on taxpayers reflects a bizarro worldview where government competence is deemed ideological.

The reality is that it is hard to believe that anyone who has studied the current tax reporting system — and is not in hock to the tax preparation industry or wealthy donors who want a weakened IRS — could come to the conclusion that there is not vast room for improvement.

Can the government do better?

I am optimistic now about the the capacity of government to produce a quality direct file system for a few reasons.

First, the IRS has enough resources to make significant investments thanks to the IRA. This had been a long-standing issue because the IRS, not unreasonably, doubted it would have enough capacity to manage direct filing. Indeed, that is one of the key reasons it entered the doomed Free File partnership with Intuit and others.

Second, the resources available to build digital government capabilities are changing dramatically. The rise of a civic tech community that could inform this work is a potential game changer. For example, Code for America, who were brought in to help the IRS reach families with the Child Tax Credit, have already outlined what an alternative tax reporting system might look like. Their involvement broadens the conversation about what is possible. [Full disclosure, I am working with Code for America in other policy areas].

The civic tech community became engaged with the federal government in the aftermath of the Affordable Care Act website failure. And therein lies another lesson. There is a strong political incentive to get any new system up and running relatively quickly. This creates a risk that a big and quick rollout leads to very visible failure. [To be fair, I’ve been wrong about this before, warning that the student loan forgiveness platform could be the next Obamacare website, when it turned out to be great]. Such a big undertaking will require a gradual roll-out, and lots of iterative testing.

Third, reporting on the tax preparation industry, especially by ProPublicia, has increased the visibility of their political influence, and by doing so, diminished their political power, making it harder for this narrow interest to quietly prevail over a collective good.

The rent-seekers are too damn high

Providing a report to Congress about the viability of a new system will not, in itself, create a new system, but it is telling that there is so much political opposition to such a basic act. It also highlights the partisan nature on certain issues of government capacity. The topic of state capacity has been gaining interest over the last few years (hat tip to Erza Klein here), but often focused on progressive failures, especially in over-regulating of private activity that makes it more difficult to achieve public goals, like building new housing and infrastructure. This is a serious and real problem, and there are other parts of the IRA, specifically environmental goals, that will be undermined by excessive bureaucracy.

But there is another side to this argument, which is that Republicans simply don’t want government to perform certain functions, and have adapted a strategy of dysfunction by design. That seems to be the case with tax collection, where overdue investments in IRS capacity occurred without a single Republican vote, even though the funding would more than pay for itself, while reducing illegal behavior and improving customer service.

The big fear of the anti-tax movement is that once people experience a free and functional tax system, they will like it, making it impossible to eliminate. But getting there requires some courage on the part of the IRS to withstand political pressure from actors who, for one reason or another, don’t want to the state to function well.

We see evidence of this courage in other spaces. The Biden administration is pushing back against private industry overcharging in Medicare, despite an opposing lobbying blitz. Another example is the new proposed rule to ban subscriptions that are easy to start but hard to stop. The solution: one-click cancelation policies benefit consumers but are bad for private industry. This is also a good example of the multi-front push by the Biden administration to reduce administrative burdens, even in private domains.

In the US political system, such actions requires giving bad news to large potential donors. It is what we want to see in public officials, but not what they are incentivized to provide.

The IRS will also have to break with some bad habits. One is the tradition of kowtowing to the tax preparation industry which characterized the one-sided Free File partnership. But if it holds its nerve it has the capacity to move forward in building a large and lasting improvement to US government.

The private tax preparation industry will still be in business, for those who have more complex tax situations or those who distrust the IRS, and if it provides a better product. It will have the freedom to market itself through Super Bowl ads in the way the IRS will not. If you want to support it, you will be able to.

But US taxpayers deserve a functional tax reporting system, one whose capabilities are defined by what is possible, not what is profitable, built by those who want that system to work rather than by those who want it to fail. Whatever about the technical and political questions that are playing out, the moral ones are fairly clear.

I strongly suspect but cannot prove that this calculation was inspired by Matthews’ love of Margin Call, where Stanley Tucci’s character “waxes nostalgic about his prior career as a structural engineer, building bridges that helped actual people” by estimating that the resulting reduced commute time meant “a combined 1,531 years of their lives not wasted in a fucking car.”

When California designed its own version of return-free filing, taxpayers loved it, but Intuit invested enormously to kill it, and to send a warning shot to other politicians. As Pam Herd and I recounted in our book, Administrative Burden, the designer of the California system noted that once Intuit spending took off, calls from from policymakers seeking to emulate what he had done stopped: “It was a huge signal to politicians everywhere how much Intuit cares about this. People in other states who had been interested in it started saying, ‘We just don’t want to pick a fight with Intuit.’”