The matching-to-categories problem

A food-stamp experiment shows how mundane administrative categories can have a large effect on benefits

State-created categories are important — they literally define us. Debates about the racial identities included in the Census are a classic example of how we think about the construction of such categories. This is a story about how more mundane administrative categories matter in everyday encounters with the state.

A new experiment shows that people’s success at matching to administrative categories matters to whether they receive benefits to which they are entitled. The good news is that governments can learn how to present categories in intuitive ways that help the public.

We (myself, Pam Herd, and Eric Giannella and Julie Sutherland of Code for America), found that better presentation of the category of “self-employed” led to about a one-third increase in claimants selecting into this category, thereby allowing them to claim larger SNAP (food stamp) benefits. Our paper is available at the Journal of Public Administration Research & Theory and a preprint can be found here.

A category mismatch

We are surrounded by state-created categories (in fact, we are state-created categories)

In Harold Lasswell’s classic definition of politics – “who gets what, when, how” – a basic task for the state is to establish formal categories that determine the “who” that gets “what.” Determining “who” is disabled, or white, or homosexual is not straightforward, and has significant effects on the individual’s relationship with the state, including the rights and benefits afforded to them.

Administrative determinations of “who” come in two stages. In the first stage, the state develops formal categories, as well as criteria that assigns people to those categories. The contesting and consequences of racial categorizations, for example, are closely observed.

There is a vast and rich literature on processes of state categorization from disciplines such as anthropology, philosophy, history, sociology and multiple sub-fields of political science.

What are some of the key lessons from this literature? First, one benchmark of the developed administrative state is its capacity and desire to categorize and measure, and to enforce its categorizations and measurements upon the populace. The development of state-defined standards for categories such as property, crops or weights make the subjects of the state legible to their rulers, and thereby made it easier to tax those subjects and facilitate other goals such as trade.

Second, state categories are constructed, rather than found in nature, even as they seek to capture real phenomena. Categories are, therefore, mutable, reflecting values and political pressures of the particular time of their creation. Perhaps the most obvious example of this is the construction of racial and ethnic categories by governments. Consider some of the options for those living in North America over the last 250 years. In the late 19th century, Blacks or Indians living in portions of New Spain that became much of modern United States could purchase certificates issued by the Spanish Empire that changed their racial status, allowing them to claim whiteness as a category. In the United States itself, categorizations ranged from the dubious “one drop of blood” standard, to the construction of Hispanic and Latino as distinct categories, to the de-ethnicized standard of “White” as a category. A recent example is a push for the creation of a separate category of Middle Eastern and North African in the Census, since many falling into this category do not see themselves as White and are not perceived as such by others.

Once these classifications are asserted by the administrative state, they become increasingly perceived as the natural order of things, disguising the choices, tradeoffs and decisions that went into their creation.

Third, classifications can have significant consequences for the subjects of the state. The consequences come via different mechanisms. The category might serve to exclude or include, hide or recognize. The category of a “regular voter” – those who have voted in one of the last three elections for example – exists to exclude people from the voting rolls. The category might make them vulnerable to punishment in some way. Categories have a way of “making up people” into legal – and punishable – classifications such as pervert, prostitute, vagrant, loiterer, or homosexual. In our experiment, different categories mean different benefits for citizens, and selecting the wrong one means leaving money on the table.

What is the matching-to-categories problem?

In the second stage of administrative determinations of “who”, the individual is matched to the appropriate category. In many cases, this can be straightforward, particularly in cases where people don’t contest the category or the placement of themselves in it. But in some cases, the categories and criteria are ambiguous, and it is left to the individual to judge which category they fit into.

Matching requires time and effort, and failure to match to an advantageous category can mean a loss of material benefits. The matching problem may sometimes result from obscure categories. Should immigrant family members of US citizens apply for the IR3, IH3, IR4 or IH4 visas? The matching problem is also amplified when the state uses identity categories where individuals hold pre-existing beliefs about such identities that map poorly onto equivalent state categorizations. While we normally think of identity categories in terms of race, ethnicity, nationality, gender, and sexuality, they include other characteristics such as self-employed or unemployed, a retiree, parent, dependent, eligible voter, spouse or disabled. Such categories can matter a great deal if access to rights or resources is tied to fulfilling those categories in the eyes of the state.

For example, not having a job is not equivalent to the state category of being “unemployed” which comes with many other criteria. Lets take two other examples of the matching-to-categories problem in the social safety net.

First, category mismatches around who qualifies as a “parent” explains the majority of EITC improper payments, which constitute 24% of the program’s expenditures. Non-resident biological parents, resident or nonresident boyfriends, and even grandparents and aunts, claim the status to increase deductions. For applicants, such claiming of categories might reflect the realities of caregiving in complex family situations. Confusion may also arise from the complexity of the tax code: the 2020 IRS EITC guide runs to 41 pages, and it is possible that a child might be categorized as a “dependent” but not a “qualifying child.” Such misclaiming frequently triggers concerns about fraud, such that EITC recipients face higher audit rates than wealthier taxpayers.

Second, the status of “retiree” seems straightforward enough. The work of defining eligibility for Social Security retiree benefits is largely undertaken by Social Security based on administrative data. But the presentation of retirement categories by Social Security still affects how people think about their retirement decision. More specifically, participants understandably confuse “Full Retirement Age” with the age when Social Security retirement benefits are maximized, which is in fact “Delayed Retirement Credits.” An experiment that relabeled those categories to Standard Benefit Age and Maximum Benefit Age, respectively, resulted in not just a more accurate understanding of the categories but also made people more likely to say they would delay retirement.

The experiment: helping the self-employed claim a SNAP deduction

To study the matching problem and ways to reduce it, we undertook a field experiment in a California welfare program, CalFresh, the state version of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Claimants often fail to select into the category of “self-employed” even though it would be more favorable for them to do so, allowing them to claim a higher deduction. For example, for a two-person household earning about 70% of the federal poverty level, claiming the self-employed deduction increases the value of the CalFresh benefit from about 19% to 28% of their income. In other words, the self-employment category is quite valuable.

“Self-employed” as a category has become less clear as the gig economy has expanded. The number of people claiming self-employment under SNAP has increased from about 365,000 in 2006 to 939,000 in 2018. But many of those who are eligible do not understand they fall into the administrative category of self-employed. For example, many gig workers who work for app-based companies like Uber or GrubHub may not see themselves as ‘sole proprietors’, which is how California describes the self-employed. By one estimate, 17% of California SNAP eligible households have self-employment income, which is far more than the rate claiming the deduction, as we detail below.

The experiment was run on the GetCalFresh website, which accounts for more than half of California applications to CalFresh. Code for America, the nonprofit that runs GetCalFresh, is an example of a broader civic tech movement dedicated to making government technology work for the public. I’ve gotten pulled into this world because some folks from the tech community found my research on administrative burdens with Pam Herd useful, offering them a framework to describe much of what they were already doing.

The field experiment contained two treatments administered to actual applicants. The first treatment sought to reduce learning costs, making the category of “self-employed” more intuitive for users. How did we figure this out? By talking to people. We consulted with eligibility workers, advocates who help people sign up for benefits, examined income verification documents, and talked to low-income Californians about which terms were most understandable. The result was to provide more intuitive terms and relatable examples, information about benefits, and access to more information if needed (see below). (They also point to the importance of qualitative research in well-designed administrative solutions, but that’s another story).

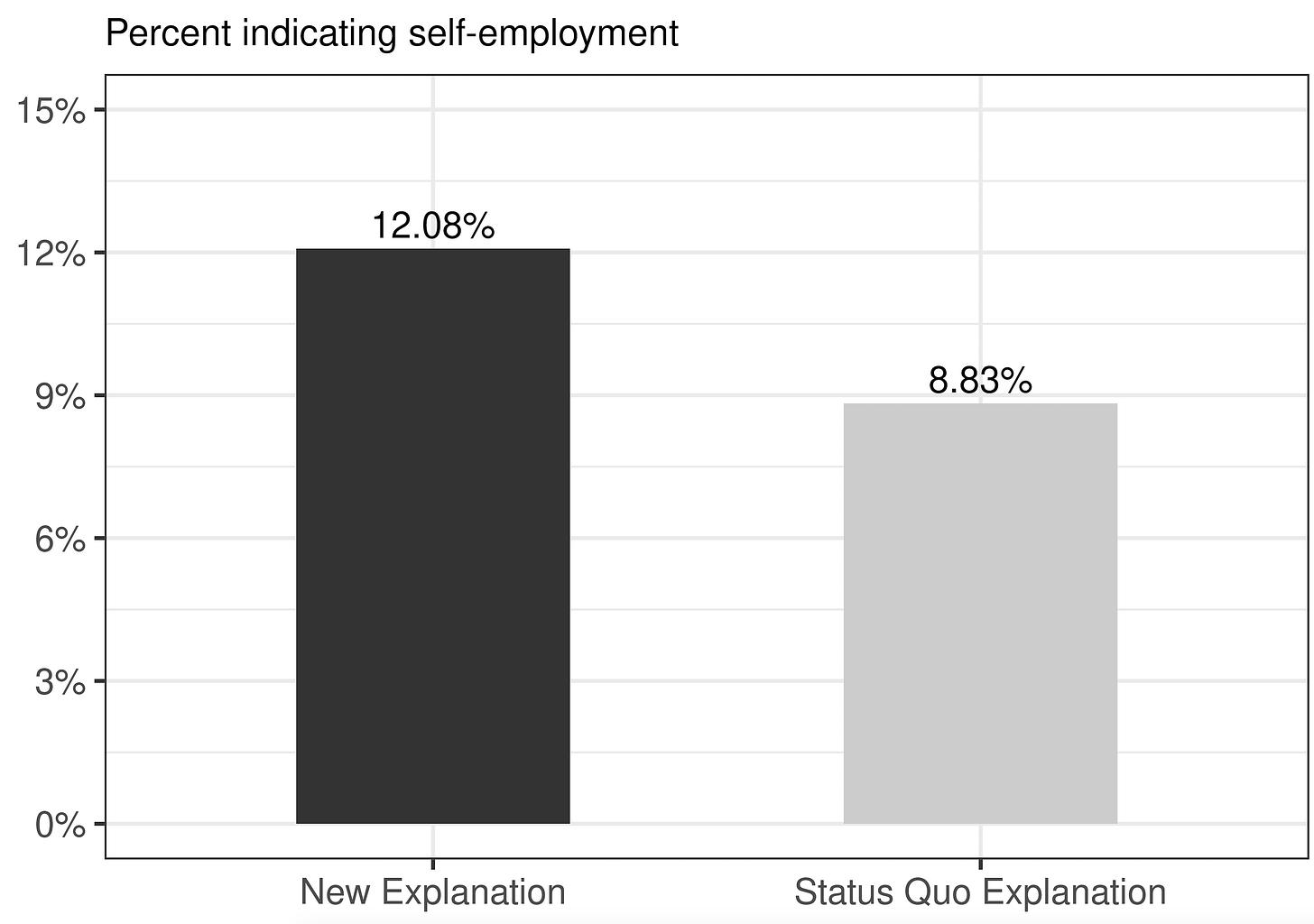

This treatment increased the rate of those declaring as self-employed from 8.8% to 12.1%, or about one-third. The experiment worked so well that Code for America adopted it as their new default.

The second treatment dealt with the problem of documenting whether the applicant fell into the self-employed category. To do so we provided a self-attestation template (see below). In other words, we gave applicants a model letter to complete, guiding them to include personal details in a format that in most cases the state will accept. This treatment sought to reduce both learning costs — since many self-employed individuals would not know what serves as acceptable documentation — but was primarily intended to reduce the compliance costs of providing documentation - since self-employed people don’t typically have access to documentation that companies provide to employees.

Of those offered the template, 22.8% used it, making them significantly more likely to provide an acceptable form of documentation to state officials.

One risk here is that our experiment worked by encouraging people to select the wrong category. Fortunately we could check against this risk. Members of the research team reviewed documents submitted by participants on the first day of the study. These immediate checks gave no cause for concern – people appeared to be correctly identifying themselves as self-employed and the self-attestations contained the necessary information. We could also observe that the applicants exposed to the new language and using the self-attestation template were approved by state officials at the same rate as others claiming self-employment status, implying that the treatments increased the success of claimant’s ability to match with state categories.

Some practical implications

There are some pretty straightforward lessons for how governments work. The construction and interpretation of everyday and seemingly mundane categories offers a fruitful place to devote a lot more administrative energy. Such categories may have been rendered invisible by use to administrators who see them everyday, while still proving baffling to members of the public who don’t.

A good deal of “nudge” research has looked for low-cost ways to help people make better decisions, though informational treatments such as reminders, providing social comparisons (e.g. telling you that your neighbors use less electricity than you), or changing default choices. The presentation of administrative categories offers another venue for low-cost improvements.

While administrative categories themselves might be relatively fixed, the presentation of categories is not something that typically requires changes to the law or rules, but can be modified with relative ease. In other words, it is an under-appreciated aspect of bureaucratic discretion, where enterprising administrators could invest some time and effort to help the public solve the matching problem. There was nothing technically difficult about our study, which involved talking to caseworkers and recipients about what categories mean, and testing whether different presentation of categories were easier to process compared to the status quo. Our findings suggest not taking for granted taken-for-granted categories, but actually examining if they could be made easier to negotiate by members of the public.

If you found this useful, please check out the archive including these previous posts about administrative burden, consider subscribing if you have not done so, and share with others!