Where does free speech end, and harassment begin?

Also, that time Glenn Greenwald accused me of murder

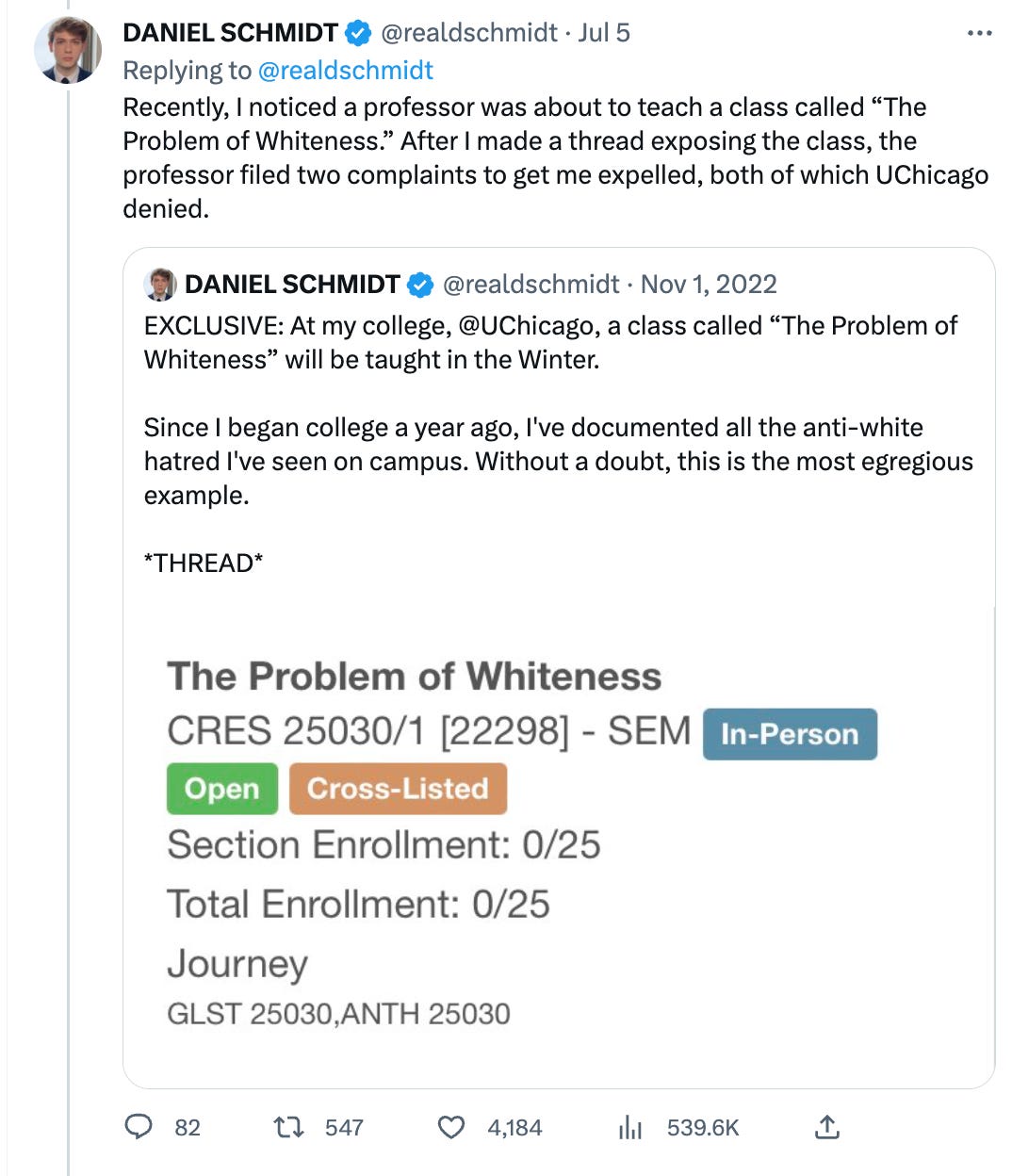

She taught a course at the University of Chicago called “The Problem of Whiteness” which addresses what construction of whiteness as a racial category means. A student tweeted it was “anti-white hatred” alongside a photo of the professor and her email address. She received a wave of vitriolic messages, including some which could be reasonably read as death threats. She complained to the university. He continued posting her image and email. The harassment also continued.

How do we make sense of this case? It complexifies the standard free speech narratives. But if you have been paying close attention to dynamics of speech on campus, a lot of it is very familiar.

Who holds power?

Discussion about campus speech is often, indirectly, narratives about power and the claiming of victimhood. Sometimes it is that administrators or professors are imposing their views on students. Sometimes, a group of students are imposing their views on professors. But the standard narrative is that conservatives are the self-censoring victims here, and woke actors the perpetrators. This narrative has largely elided the role of the state, especially red state politicians seeking to censor what they consider to be wokeness.

In this case, the conservative student is harassing a teaching fellow, Rebecca Journey, who is working at the institution where she recently received that PhD. This is not a secure position in most universities. If she seeks a full-time, tenure-track job, will other universities want the hassle of the controversy that will follow her?

Her subsequent complaints about the student are dismissed by the university, who say that the student is merely using his speech. Maybe so, but in some tangible way it comes at the expense of her speech. The student crows that the class had been cancelled. This was false. But it was postponed, and re-offered as an (I’m not kidding) undisclosed, secure location on campus.

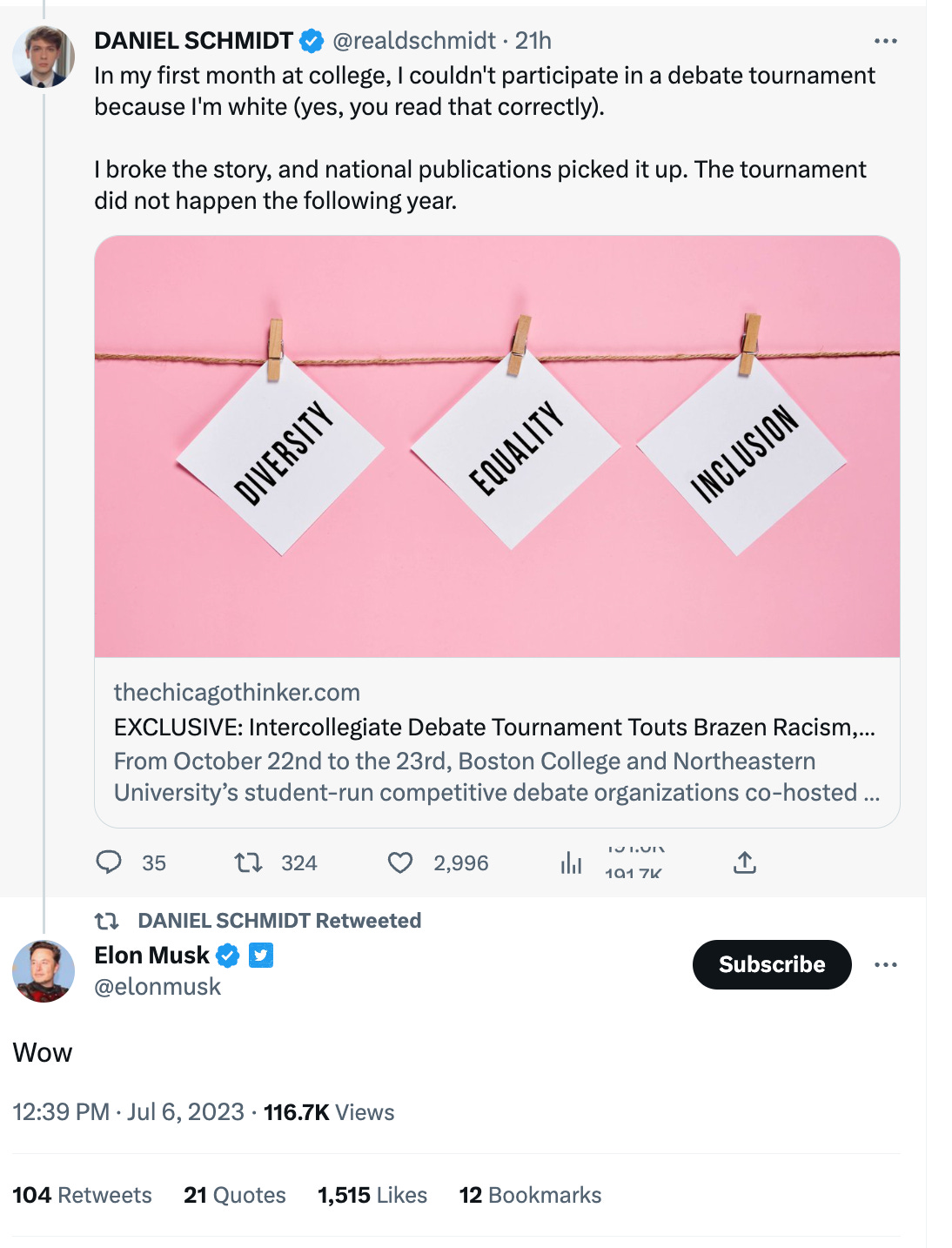

So who has power in this scenario? Schmidt’s power derives from the online media. He has has built up tens of thousands of social media followers. Elon Musk just responded to his complaints about academia:

Boosting unverified claims from the far right with a reply is something that Musk does a lot, triggering a massive increase in views. In doing so — and it is systematically far right content, not some random draw of Twitter users — Musk both directs the conversation and elevates who gains attention on the platform.

What is the effect of Musk’s intervention in this case? The first tweet in the thread Musk is replying to has been viewed 1.9 million times in a day. Within the thread, a tweet linking to the original thread about the “Problem of Whiteness” course has rolled up almost 540K views. In this thread is, again, the picture of the instructor, and her email.

What do you think happens next to the professor’s inbox or sense of personal safety after Elon Musk has helped to elevate the original criticism of her to an even larger audience?

They know what they are doing

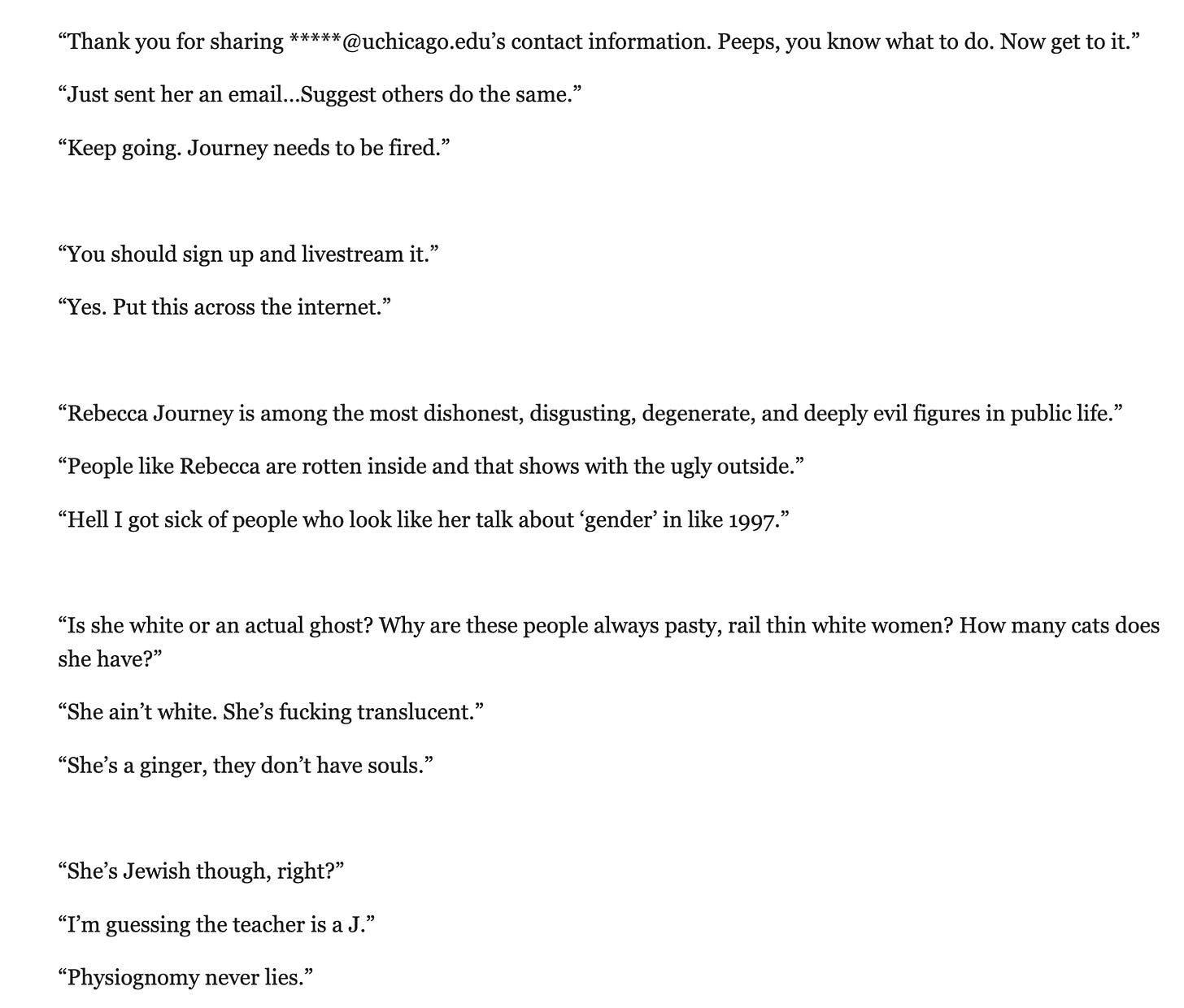

The student says he did not intend for the instructor to be harassed. After all, he did not send the emails. He can’t be held responsible for them.

He also says that anyone could have found her email and name. All of this is public information.

True. But in writing about her experience, the instructor noted that the replies of followers to Schmidt’s original tweet. Many saw Schmidt’s message as an instruction. They would not have searched for the class, or her email, without his guidance. And they signaled their intent to harass.

How you feel about Schmidt’s responsibility here probably reflects how you feel about the idea of “stochastic terrorism”, i.e. that high profile actors directing attention toward people they disagree with, usually in an incendiary and often misleading way, creates some responsibility for how their followers respond.

Is Chaya Raichik responsible for the death threats and bomb scares that health providers and teachers experience when she identifies them on her LibsofTikTok account? Is President Trump responsible when, after he posts President Obama’s address on Truth Social, a deranged Trump supporter turns up in the neighborhood with guns, pledging to get “good angle on a shot.”

Taken to an extreme, we might end up censoring any public criticism if we played “what ifs” about the potential fall out. I am, after all, criticizing the student’s behavior. I surely hope that readers have the good sense not to engage with him, but do not consider myself responsible if they do.

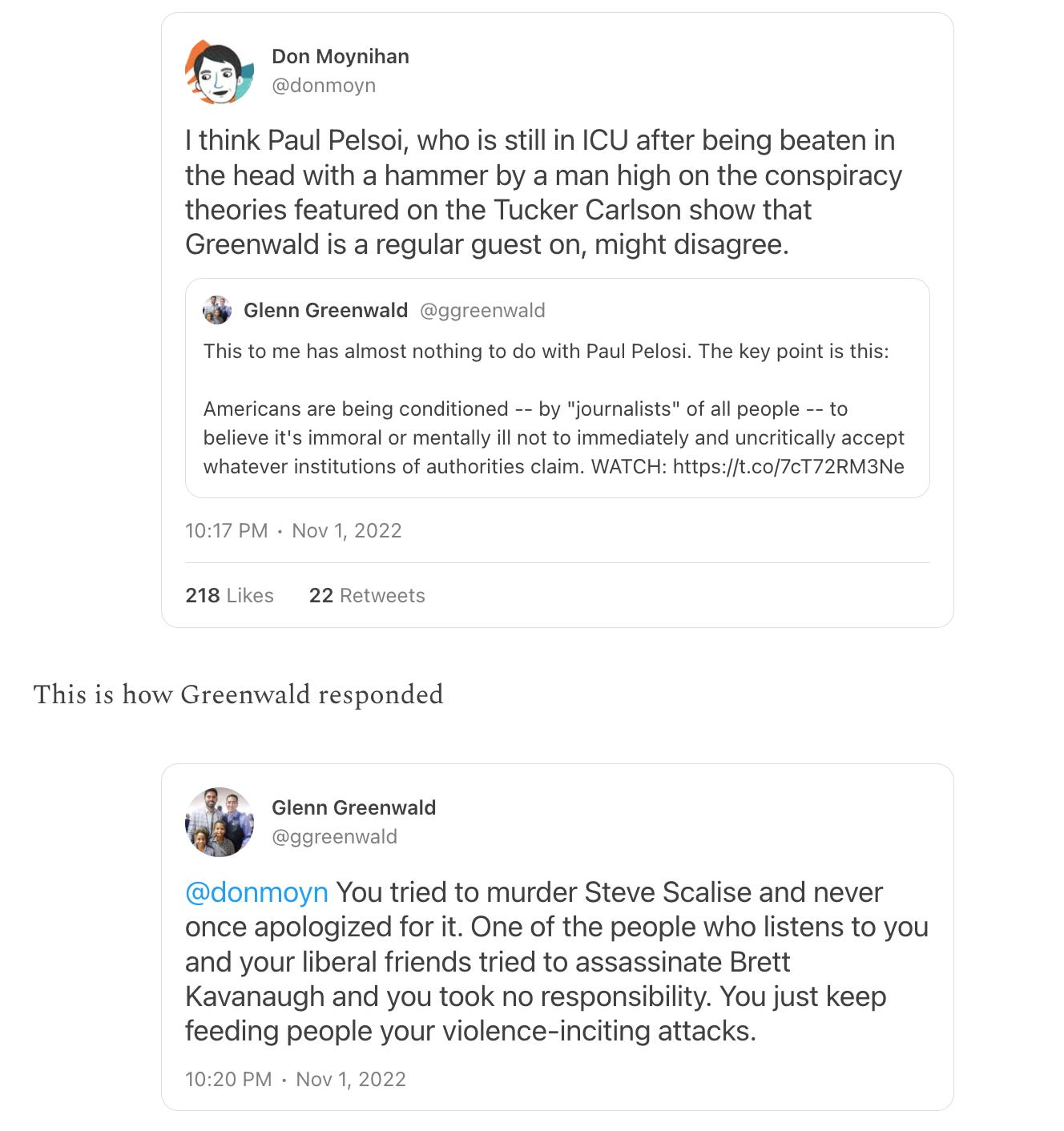

Side note: Maybe I am overly sensitive to this topic because Glenn Greenwald once accused me of being responsible for the shooting of Congressman Steve Scalise.1

What???!!!

I posted after Paul Pelosi was attacked by a man who had gone down the rabbit hole of right wing conspiracy theories.

(Not coincidentally, both Musk and Greenwald would also suggest there was something suspicious about the Pelosi attack. Just asking questions you understand, pushing back against the mainstream narrative. The violence that conspiracy theories spawn are ripe material for more conspiracy theories).

Back to how to assign responsibility here: honesty, intent, and acknowledgment of damage matter.

It matters if the claims are misleading, often in a way designed to arouse negative emotions and hostility. Does the professor actually hate white people? Is there really anti-white institutional bias? If you look around at the seats of power at the University of Chicago or other elite institutions this claim has little face validity, but a lot of people have been primed to believe it is true.

It matters if we have good reason to believe that the actor intended the outcome that emerged. Why else post the email, or picture? In doing so, he was doing more than making a general point about academia, but directing a certain type of attention to a specific individual.

It matters that the actor dismisses the evidence of the outcome of their actions. He has shared her image and email address repeatedly even after complaints that this triggered abuse. Such a dismissal and doubling-down is consistent only with a belief that she, in some fashion, deserves what is coming to her, and he is entitled, nay, obliged to be the instrument of her intimidation.

Cyber-harassment as a function of new media and incentives

Schmidt can be understood as a figure arising at the intersection of new media and incentives. The new media is partly social media, but also online right wing reporting. As I previously wrote:

It is hard to overstate how much of this media ecosystem is a new feature of American society, and one that is financed or directed by the conservative billionaire class. Breitbart was created in 2007, the Federalist in 2013, the Daily Wire in 2015, the Daily Caller in 2010, the Washington Free Beacon in 2012. Campus Reform was created in 2009. Such entities do not just support each other; they rely disproportionately on the same set of funders: The Bradley Foundation, the DeVos family, the Mercers, Paul Singer, the Uihleins, and Kochs.

Beyond his social media following, Schmidt had interned at the Daily Wire, and appears on TV, most recently on Fox.

In short, he has a sense of how the new right wing media works, playing on populist themes of powerful institutions as being anti-white. His story gained traction within this media…

…and he even gained a second round of coverage when the instructor complained to the university about him.

Schmidt is a particular type of right wing creature — one who sees the new media as a ticket to fame, or if not fame, infamy. Campus conflict offers the road to get there. The student has created his own website, and is staking out a space in a conservative media landscape that falls somewhere closer to Nick Fuentes than Ben Shapiro. He posts largely about campuses — too much affirmative action, anti-whiteness, feminism, and pro-Jewish thought. He also posts videos of himself asking guest speakers at public University of Chicago events about Hunter Biden’s laptop or a discredited conspiracy theory that a January 6th participant named Ray Epps was an FBI informant. (Those videos are also part of the thread that Musk elevated).

Schmidt is not alone in seeing campus conflict as a stepping stone to bigger things. Others have played the role of cancelled campus speaker, or tagging excess wokeness. It’s fertile ground, because, as Bari Weiss once noted “campus craziness sells.” It sold for William Buckley when he wrote God and Man at Yale in 1951 and it has a much bigger audience today.

Actors like Schmidt can take advantage of campus institutions characterized by both openness and commitment to free speech. If you find yourself scoffing at this idea, consider how many private companies would have not fired someone engaged in an ongoing campaign of public harassment of a company employee while routinely disparaging the company itself.

It’s not actually about what the professor is teaching

It would be a mistake to assume that the student actually cared about what the instructor would cover. He read only the course title. Not the syllabus. Or the readings. He never attended a class. (For anyone interested, she talks about what the construct of whiteness means here and how she would have taught it).

This is unsurprising. Previously, a co-author of mine was involuntarily profiled on the Tucker Carlson show after one of his students read a syllabus, but before she took a class, which, she later admitted, was actually pretty fair. But not before the professor received a deluge of hate mail and death threats, a stranger accosting his child, and the head of the state legislature higher education committee sending an angry missive to university leaders suggesting someone else teach the course. When I was faculty at University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2016, another faculty member was threatened with firing, and the entire university with a budget cut after he offered a class called…drumroll please…“The Problem of Whiteness.”

In Florida, courses that make explicit reference to race and gender are being dropped or renamed. This is not based on close reading of the texts, and finding them objectionable. Simply engaging with discussion of how race and gender is related to power is, by itself, an objectionable act, one so threatening that it must be censored, by the state where possible, and by campaigns of harassment where not.

Harassment may be a form of speech, but a culture of harassment is at odds with both speech and learning

Just as there is a new incentive structure for students like Schmidt, so too is there a new incentive structure for the instructors who teach them. Relatively few instructors on campus enjoy the security of tenure, and even those that do are reluctant to be the object of hate and intimidation, or have their careers derailed if they are fed into the campus outrage machine.

If you came to campus looking for debate…well, you should probably want something more, but publicly attacking the people teaching you is only going to erode the basis for that debate, which is as much about securing trust around norms of engagement as it is about guarantees of speech rights. Who would want to be a professor, or fellow student, with Schmidt in the classroom?

Key actors are struggling with these new realities.

Traditional media has been all too easily co-opted by the complaints of the new right wing media, adopting their framing and mainstreaming their stories. What was most remarkable reading the New York Times account of the case is that this was the first time I can recall where it framed its initial coverage of a campus speech conflict by providing context about the role of far right media.

Campuses themselves don’t know what to do. The University of Chicago has defended the rights of both the student and instructor. Their vaunted free speech principles were not written for the current era of cyber bullying, where their employees can be involuntarily turned into national figures of hate. Being featured in the new right wing media predictably leads to harassment and threats, especially to women and faculty of color.

For free speech advocates, like The Fire, it also exposes some blind spots. The organization has spoken out about this case, backing the right of the instructor to teach the class. But the issue of harassment of faculty fails to make it in The Fire’s efforts to measure campus speech. If a student, staff or instructor was disciplined for speech issues, or a visiting speaker interrupted, that would be carefully compiled in Fire’s rankings of free speech on college campuses. But targeted harassment is not, perhaps for the reason that speech advocates, and college administrators, struggle to define where free speech ends and bullying begins.

Even more troubling with cases such as this is that it challenges the idea that the solution to bad speech is exposing it with good speech. This idea is at the core of much free speech advocacy. It puts too much faith in debate. We have more good speech than ever, and more conspiracy theories too. It also fails to acknowledge that some forms of speech are in tension. Such an acknowledgment would demand a consideration of uncomfortable tradeoffs. Are we willing to punish harassment? And who decides what harassment looks like? Or, must we simply accept toxic campaigns of intimidation as a new feature of campus life, the price of other types of speech?

These are not easy questions. I don’t have clear answers. But I do think it is worth pointing out that such tensions are real, and worth considering, rather than blithely ignoring them.

Greenwald was, I believe, trying to be ironic, but is not good at it. One reason is that his go-to-tone is histrionic - everyone who disagrees with him is corrupt, a shitlib etc. This makes it difficult to switch to the more detached posed of irony. I think his point is that any criticism can be elevated to baseless claims of incitement to violence, which is fair. But it also conveniently absolves him or his right wing media colleagues for any responsibility for the conspiracy theories they elevate to millions.

Can we create a “the first step to recovery is admitting you have a problem” movement? With the firm recognition that there are no easy answers, only difficult tradeoffs?

“We have more good speech than ever, and more conspiracy theories too. It also fails to acknowledge that some forms of speech are in tension. Such an acknowledgment would demand a consideration of uncomfortable tradeoffs. Are we willing to punish harassment? And who decides what harassment looks like? Or, must we simply accept toxic campaigns of intimidation as a new feature of campus life, the price of other types of speech?

These are not easy questions. I don’t have clear answers. But I do think it is worth pointing out that such tensions are real, and worth considering”