Can we tell a different story about campus speech?

Gavin McInnes, and the theater of cancelation at Penn State

Read this headline in the New York Times

The Washington Post headline:

For those skimming the headlines, the takeaway seems clear: another controversial speaker shut down by woke students!

The Times frames the piece with an all too familiar narrative:

Protests against conservative and right-wing speakers on university campuses in the United States have focused national attention in recent years on the question of whether campuses are shutting out politically unpopular points of view.

Penn State’s first statement immediately after the cancelation was not much better bemoaning censorship.

There are better ways to report on and think about debates about campus speech. Let’s consider a few.

The perspective of those who cover extremist groups

The invitees to the Penn State event were Gavin McInnes, the founder of the Proud Boys, and Alex Stein, best known for, uh, yelling lewd insults at AOC in a desperate attempt to gain notoriety.

The Proud Boys are not the Club for Growth. It is not just that their views are radical, but they are best known as a street-fighting gang that instigates violence, including playing a significant role in the assault on the Capitol on January 6th. McInnes has repeatedly advocated for violence. Reporters familiar with the group saw the event through that lens.

Andy Campbell at Huffington Post wrote about what happened not from a free speech perspective, but as part of a pattern of violence and disruption he has documented in his reporting on the Proud Boys. He also drew on local reporters that recorded that Proud Boys had instigated violence, without any apparent retaliation from students. This willingness to actually cast blame was missing from the university statement, which was then reported by the New York Times: “It is unclear which individuals on-site then resorted to physical confrontation and to using pepper spray against others in the crowd, including against police officers.”

The tactics of the Proud Boys are transparent to reporters that cover extremist groups: go to a site of potential conflict, start something, and then blame the other side. The outcome of the event was also entirely predictable.

The campus invited someone who founded a street-fighting gang best known for trying to assault liberals. Some of them came on campus and assaulted liberals.

Reporters on the ground

Tess Owen, who also covers extremist groups for Vice, was on the ground. Her reporting provides even more context.

For example, she reports that some two-dozen students who labeled themselves the Student Committee for Defense and Solidarity did want to shut down the event using fake tickets to enter the talk which they then planned to non-violently disrupt. A posse of uniformed Proud Boys were also there, and at least one of them sprayed the crowd and reporters with mace.

This is probably the clearest view of what happened. Per reporting, police — who had been fielding a steady stream of insults from protestors — made no effort to detain the assailant, though giving the crowd and masking it may have been difficult to identify that person.

The university administration and campus police had all the excuse they needed to shut the event down.

The immediate cause of the violence, and cancelation, was the organization founded by the speaker invited for the evening. McInnes was canceled by his own supporters, who value violence over words. Their actions prevented students who planned to disrupt the event from putting their plan in place, but the students were at least partially or completely blamed anyway.

The campus outrage machine

If you do not live on campus or follow these stories of free speech closely, you might easily think that these events just happen. That is incorrect. The events are constructed.

They are not, by and large, driven by students or faculty interested in campus speech. They mostly feature outside speakers, often promoted and covered by outside organizations that seek to undermine higher education institutions.

The reporting in the New York Times provides little about Uncensored America, the group that invited McInnes, except that it was founded by a Trump campaign official. They are quoted as saying they welcome all viewpoints.

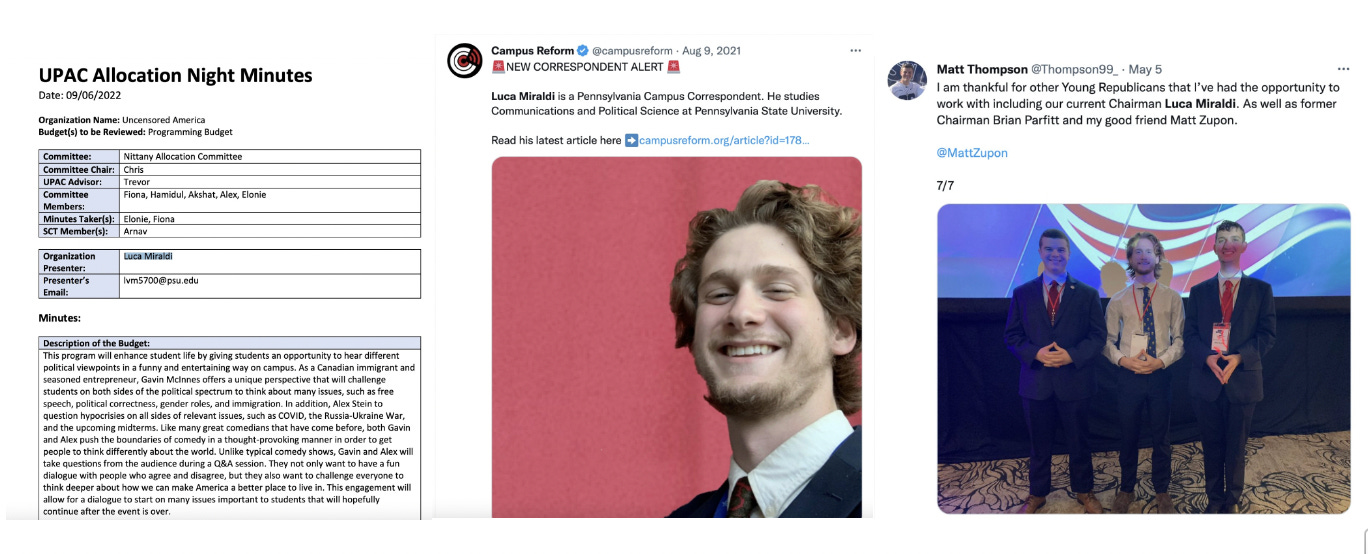

We do not learn that the McInnes event was organized by a PSU student who is also a Young Republican and a correspondent for Campus Reform, whose Koch-funded operation whose sole purpose is to complain about liberal intolerance.

So step back, and you see a different story. It is one of cultivated outrage designed to undermine institutions. Right-wing actors establish organizations that bring right-wing speakers to campus (see also, YAF, Turning Point). Right-wing students rely on the general commitment to free speech of universities — once an invite is extended, universities are loath to prevent a speaker from coming. If the event careens into violence or is disrupted, blame the students, blame the university. Sometimes the blame is justified, though that does not appear to be the case here. It helps that the same actors stoking the outrage have created their own media to report it.

It’s a well-funded and well-oiled machine designed to generate controversy, framing and clicks

All of the information I have shared with you is public. Why the Times or other chose not to include it is unclear to me. It could be that they judge the on-the-ground sources as less reliable because many are independent journalists. But by not doing so they return to the familiar crutch: conservative speakers can’t be heard on campus because of intolerant leftist students.

McInnes at PSU will become another shorthand for student intolerance, as emblematic as the Dartmouth students complaining about cultural inauthenticity of bánh mi sandwiches. That the story was not true, in either case, does not matter. It fits a narrative that the national media cannot break themselves from.

The campus outrage machine rumbles on because some actors clearly benefit from it, and those that don’t can seem to switch the script. Gavin McInnes, a man who has routinely advocated violence against people he disagrees with, and then watched his supporters act on that advocacy, can present himself as a victim. “I was clearly censored” he told the Washington Post. Uncensored America, largely unknown, now finds itself in the national media, offering banalities about valuing all sorts of speech and opposing violence, statements at odds with their actions.

Who loses? Students do to a great extent. They continue to be portrayed as intolerant, because some of them protested. Students are generally more tolerant of contentious speech than the rest of the public according to surveys, but they are being held to an impossible standard applied to no-one else. If even a small number of them responds to a provocative speaker, they are broad-brushed as woke radicals.

University administration also loses. Despite what you might have heard, such administrators are generally supportive of free speech and viewpoint diversity. Even if they don’t personally believe it, they must cater to important stakeholders, such as state officials, donors, regents, who want more conservative voices on campus. So they will uphold invitations to people like McInnes even if they believe he is a terrible choice.

Here is a thought experiment: what would happen in most places of work if an employee or client invited someone associated with a terrorist organization to give a talk, and then asked the CEO to honor the invite? Would they employee still have a job? By contrast, university presidents are expected to honor such invites. They will expend hundreds of thousands of dollars in security as a credible commitment to those values.

I don’t know how we fix this. At this point all of the actors seem to be pre-ordained to play specific roles, some knowingly and to their benefit, others less so. In this case it was entirely predictable that there would be violence and cancelation. But no-one seems to have figured out how to break the cycle.

The story not being told: how speech as a form of power is being eroded for students, staff and faculty

Framing matters, because we remember the frames, not the details of a specific case. The campus speech battles have framed speech in a very specific way: is it free or not? That is an important criteria to be sure, but there are other ways to think about speech.

If you care about the quality of speech, you don’t invite Gavin McInnes. You invite him only to test the boundaries of speech and provoke a response. See also, for example, Berkeley College Republicans inviting Ann Coulter: invite bad speakers to get local relevance and national media attention.

There is a broader story of speech on campus also. It is speech as democratic power. Campuses honor, to varying degree, the idea of shared governance, i.e. that faculty, staff and students have a say in how the campus runs. That idea is under attack in various ways, including the weakening of tenure in some states, or clampdown on student media.

Some of the most important changes are invisible. State politicians or university administration are less likely to invite students or faculty to play a role in making key decisions, or even bar them from doing so. The use of procedural and structural power to erode speech drains it of the sort of conflict that generates the press that McInnes enjoyed, leaving those who are losing speech on campus with few alternatives. It has not been framed as a national crisis equivalent to the supposed wave of student intolerance.

These erosions to speech as democratic forms of power are not unrelated to other constraints on speech. Remove a seat at the table, and people are left protesting outside.

For example, the state of Florida argues in court that there is no such thing as academic freedom, and university officials suppressed academic research that ran contrary to the goals of the DeSantis administration. At the same time the University of Florida presents Ben Sasse as the sole finalist for the job of university president, in a selection process that was adjusted to avoid any transparency. At a public forum introducing Sasse, students protest even as Sasse demurs about responding to questions about academic freedom. This generates a wave of headlines about intolerant students. The university responds by banning indoor protests.

Students would not need to protest if they had a real say in the process, and now they cannot even offer their meager signals of disapproval. Their voices do not matter. Meanwhile, the same powers that put such restrictions on speech will emphasize their commitment to free speech, and viewpoint diversity, and shake their heads at woke intolerance. It’s easy to do so when you control the rules of the game, and always have the option of silencing the speech you dislike.

For more writing on speech on campus, check out these previous posts and subscribe to my newsletter if you have not already done so!