The courts as an instrument of American decline

How the conservative SCOTUS is undermining liberal democracy, state capacity, and the legitimacy of the court itself

AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin

The end of the current Supreme Court term signals a fundamental shift in American policymaking, individual rights, and state capacity. SCOTUS has declared itself to be the preeminent policymaking actor in the American landscape. By virtue of the unity of purpose offered by a 6-3 supermajority, a willingness to cherrypick cases to advance its policy agenda, and indifference to public will, past laws, administrative realities or stare decisis, the court has abandoned the traditional restraints on judicial power. In doing so, the Roberts court has rendered regular politics and policymaking processes increasingly irrelevant.

The widely-anticipated reversal of abortion rights has drawn the most attention, reflecting how abortion has been one of the most salient dividing lines in American politics for decades.

But it’s also worth stepping back and look at the broader picture. Other cases restricted Miranda rights, the ability of the state to regulate guns, plus the collapse of the administrative state’s ability to engage in basic regulation. (A comprehensive overview feels impossible, but this is a good effort). Taken together, these decisions will have extraordinary repercussions for decades, and in the case of climate change, perhaps even longer. As significant as the decisions themselves is the way in which the SCOTUS made them, which tells us much about how America will be ruled in the coming years.

The courts are moving America further away from the principles of liberal democracy

A central feature of liberal democracies is that individuals hold relatively stable rights, and those rights expand over time as individuals petition their government for recognition. After this week, this feature is increasingly difficult to discern in American governance.

It is certainly the case that the court has historically acted in anti-majoritarian ways in the past, but when it has done so to secure individual rights, it has acted consistently with the goals of liberal democracy. Now, the moment is different.

Both the Vega v. Tekoh decision that chipped away at Miranda rights, and more strikingly the Dobbs decision on abortion rights removed individual protections from state action. In a separate opinion in the Dobbs decision, Justice Thomas noted that the privacy protections that provide the basis for same-sex relationships and marriage we well as contraception are also vulnerable, and urged for the reconsideration of these rights. If you are a woman, or LGBTQ, your rights are less secure.

Rather than being anti-majoritarian, the court takes pains to argue that it is, in fact, empowering democratic processes. Alito’s majority opinion in Dobbs explained the decision would “return authority to the people and their elected representatives.” Concurring, Kavanaugh bemoaned “nine unelected Members of this Court” overturning the “democratic process” — a phrase he mentions seven times — without a trace of irony. One would think this court was a champion of democracy. Instead, one of the most notable feature of the Roberts court has been its antipathy to voting rights and representative institutions, from Shelby v. Holder and a host of other decisions, including allowing a racial gerrymander in Louisiana to go forward just days after Dobbs.

To better understand how the court’s rhetoric on democracy falls flat, let’s take the example of Wisconsin. In 2018, the court decided not to decide on a case (Gil v. Whitford) that petitioned for relief from the severe nature of gerrymandering in the state, on the grounds that no harm could be shown to the plaintiffs. Later that year, a blue-wave election saw Democrats win 53% of the vote for state legislative seats, which translated to 36 of 99 state Assembly seats. The gerrymander had worked so well that Republicans needed less than 45% of the vote to win 63 of 99 seats. With the Dobbs decision, abortion in Wisconsin became illegal, reverting to an 1849 law. Medical providers immediately stopped offering services. The Democratic Governor had called for a special legislative session to update the laws, but the gerrymander empowers the Republican legislature to, instead, do nothing. About 60% of voters in Wisconsin have expressed consistent support for legal abortion, but they do not live in a state where their preferences are translated into policy. The loss of both their rights to privacy, and the means to petition the state to correct this loss, are a direct product of choices made by a Supreme Court which sees no harm in these arrangements.

As Jake Grumbach and Christopher Warshaw point out, Wisconsin is not an outlier: in many states there is majority support for greater abortion rights than state laws will reflect. For many, the degraded quality of their democratic institutions means these preferences will not be reflected in law.

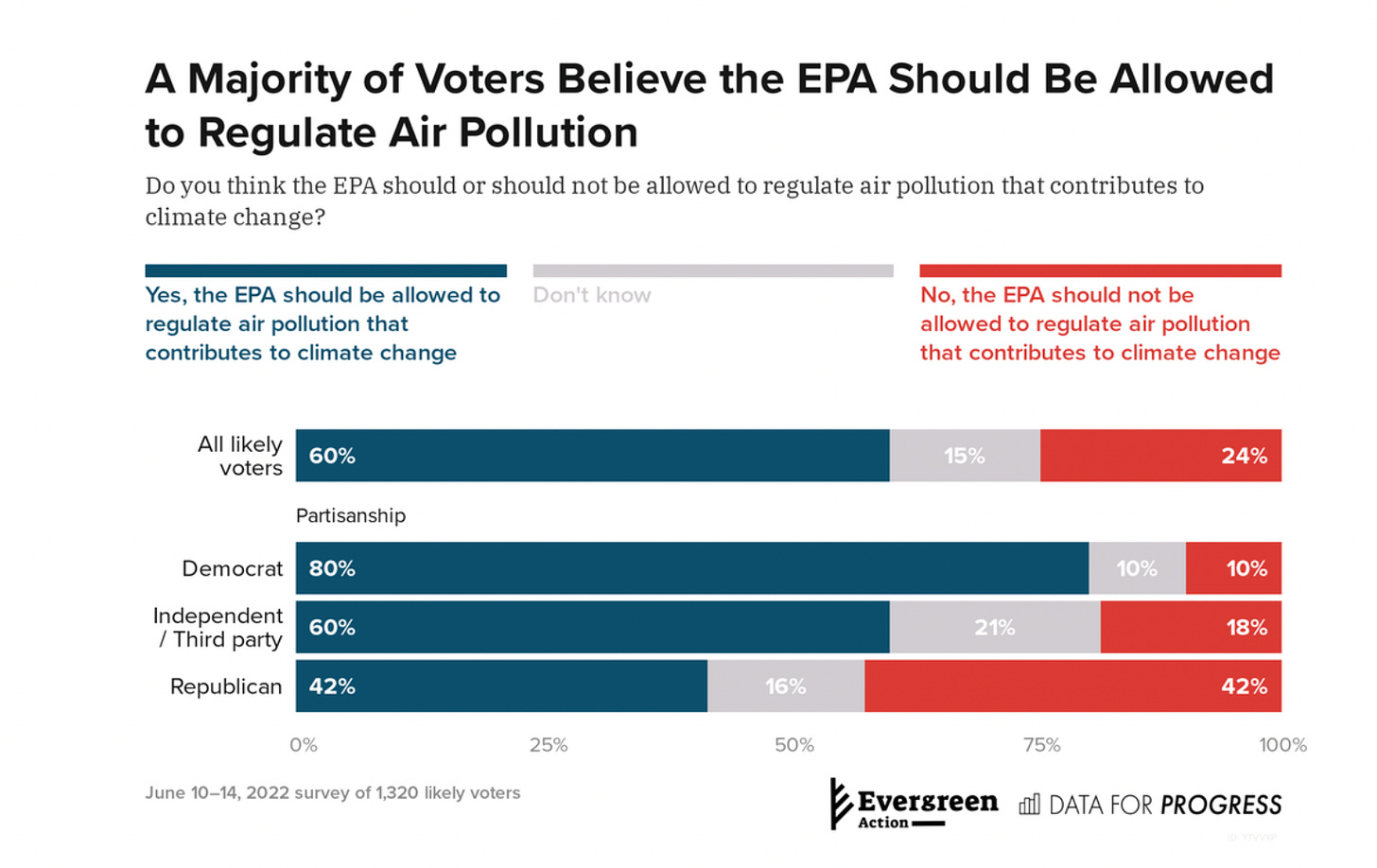

West Virginia vs. EPA has its own anti-majoritarian aspect. While voters are generally skeptical of “government” in the abstract, and of increasingly polarized institutions like Congress and the Supreme Court itself, they are more trusting both of individual agencies like the EPA…

…and the specific services they provide.

The anti-majoritarian tilt of the court underlines that it was not selected in a manner designed to reflect public preferences.

More voters have voted for Democratic candidates in all bar one in presidential contest in the last 30 years. They are represented by three Supreme Court justices. All of the votes for Clinton, Obama, and Biden across five elections have resulted in the same number of Justices as the votes for a one-term Republican President who received fewer votes than his opponent even when he won.

The court-sponsored erosion of liberal democracy will get worse. Next term, SCOTUS will consider Moore v. Harper, where North Carolina legislators want to ignore state supreme court decisions limiting gerrymandering. It would also provide the means for gerrymandered swing states to further ignore voters and choose the winner of presidential contests in their states. The case hinges on the made-up “independent state legislature” doctrine that legal theorists like John Eastman used to justify Trump’s attempted coup. But by 2024, this doctrine may be blessed by SCOTUS thanks to Trump’s SCOTUS picks, making another anti-democratic coup entirely legal.

The courts are creating an administrative state that surveils the individual but cannot solve big collective problems

What sort of administrative state is the current SCOTUS building? On the one hand, it allows for unprecedented powers of intrusion into private lives. On the other hand, it prevents the state from engaging in action to fix collective problems.

Jia Tolentino wrote in the New Yorker about the extraordinary new expectations of surveillance state women face.

In the states where abortion has been or will soon be banned, any pregnancy loss past an early cutoff can now potentially be investigated as a crime. Search histories, browsing histories, text messages, location data, payment data, information from period-tracking apps—prosecutors can examine all of it if they believe that the loss of a pregnancy may have been deliberate. Even if prosecutors fail to prove that an abortion took place, those who are investigated will be punished by the process, liable for whatever might be found.

The sophistication of state surveillance requires administrative capacity. In some cases, this means that perhaps it will be implemented poorly. But a grim irony is that state actors have shown limited appetite to use such capacity in ways that actually help families. The delivery of welfare benefits is stymied by outdated technological infrastructure and bans on data-sharing.

But even with poor administrative capacity, a state can outsource much of its surveillance function. A parallel to consider is the surveillance state we have constructed for child protective services, where the co-option of mandated reporters has resulted in 37% of all children and 53% of Black children experiencing an investigation before the age of 18. In the case of abortion, placing bounties on anyone who aids and abets the provision of an abortion is another means that some states, such as Texas and Oklahoma, will use third parties to serve as police.

The rolling back of the Chevron deference with the West Virginia vs. EPA decision guts administrative capacity. It upends almost a century of practice, long before the 1984 Chevron decision, which codified the principle that Congress needed to rely on administrative expertise to perform complex tasks such as scientifically-based regulation. While Chevron has become a right-wing bogeyman, buoyed by populist framings of the “deep state”, its critics have not offered a coherent explanation for what comes next. Will members of Congress really take the place of EPA scientists to directly regulate the environment? Undermining administrative actors will mean that expertise will matter less, political power and the resources to hire good lawyers will matter more.

With the stroke of a pen, the Supreme Court has taken a sledgehammer to the delicate machinery of government. With one decision it has done more to undermine the capacity of the state to protect our environment, climate, health, and workplace than Trump managed in four years.

The courts are ushering in an era of American decline

Recent years have been characterized by a sense of American decline — Trump supporters want to Make America Great Again, and more serious analyses have taken up the question of why America struggles to do big things. There are many potential explanations for this, but one that has not gotten enough attention is that such decline is a function of court decisions. Society has large challenges, and the court steps in to remove potential solutions to those problems without offering any feasible alternative.

The Dobbs decisions means that my daughters will grow up in an America where they have fewer reproductive rights than their mother. They will have fewer rights than their cousins in Ireland, a historical reversal, reflecting the fact that other liberal democracies are still functioning as ours is not. The reality is that women have always needed access to abortion, and outlawing it will lead to some very ugly outcomes, spread unevenly by race, class, and geography.

Guns are the leading cause of death for children in America. Mass shootings occur daily. This pattern keeps getting worse. The United States is a grim outlier relative to other developed countries in terms of the number of guns and gun deaths. Yet, in the aftermath of two especially disturbing mass shootings, the courts invalidated one of the few remaining state powers to limit access to guns, which is mechanically correlated with gun deaths. We cannot fix the gun problem in America in any meaningful sense with a Supreme Court that, rather than acknowledging mass death brought on by guns, instead keeps discovering new gun rights, rendering any new restrictions preemptively unconstitutional. The grim Onion headline: “No way to prevent this,” says only nation where this regularly happens, is the de facto constitutional interpretation of the court.

With the West Virginia decision, the capacity of the state to address fundamental issues like climate change, clear water and air, the safety of the products we consume or the places where we work, goes into what may be an irrevocable decline. It is difficult to calculate the full costs in terms of lives and misery this decision will have, but because of the nature of climate change, it condemns not just the US but also the world to a worse future. If American liberal democracy is collapsing, we are taking the world with us.

The YOLO court is undermining judicial legitimacy

If Chief Justice Roberts has a vision for the court, it seems to be that it maintains its legitimacy. He is not alone. Other Justices regularly take pains to lecture others that the court is not political, and that people need to learn to live with the outcomes the court gives them.

It is ironic that the Roberts court has done more to set in motion the decline of the institution it is so at pains to defend. Even before the Dobbs decision, public confidence in the court was at a historic low. Just 25% of those surveyed believed the court could be relied on to do the right thing most or all of the time.1

The Roberts court has engineered its own decline in three ways.

First, and as detailed above, the court loses legitimacy as it blocks society from addressing fundamental problems. This tendency is not new. In 2012, four justices on the Court were ready to dismantle the ability of Congress to provide health insurance to the public on dubious grounds. The difference now is that this group is in the majority.

Second, SCOTUS has undermined its own legitimacy via its perceived ethical failures. People can reasonably conclude that several Supreme Court judges were disingenuous at best and dishonest at worst when testifying under oath to Congress about the status of Roe, legalistic dodges about "settled law" notwithstanding. A Justice whose wife was directly involved in efforts to overturn an election gleefully considers which individual rights will be next to go. Such contradictions between espoused values of neutrality and integrity and actual practice erode trust in the court.

Third, the court undermines its legitimacy via declining consistency and restraint in judicial reasoning and outcomes. You don’t need to be a constitutional lawyer to find it suspect that a law that existed for over 100 years (the New York gun regulation) or a judgments in place for decades (Roe v. Wade, Chevron) have suddenly become unconstitutional. The principle of stare decisis, the idea that old decisions provide a precedent, is important not just for providing consistency and stability in law, but also legitimacy in legal institutions.2 Chief Justice Roberts rebuked the zeal of his conservative colleagues to brush away past laws:

Surely we should adhere closely to principles of judicial restraint here, where the broader path the Court chooses entails repudiating a constitutional right we have not only previously recognized, but also expressly reaffirmed applying the doctrine of stare decisis.

The conservative supermajority on SCOTUS claim that they are simply providing fealty to the constitution.3 They are right, they reason, and all of those prior judgments were wrong. It’s just a coincidence that the outcomes happen to match with their partisan values and the values of the politicians and donors that put them on the bench.

In reality, the rights of political allies are elevated, and the rights of those who stand in the way of the conservative vision of society —more guns and Jesus — are eroded. Gun owners are given enhanced status. The religious are given new access to public school funding, and the first amendment rights of religious teachers are newly elevated over the protection of students and the separation of church and state.

On Thursday gun rights are newly inviolable to state laws, but on Friday the right to privacy and the determination of abortion is now up to the states. On Friday, Alito cannot find a well-established privacy right for abortion, while on Monday he argues for ignoring parts of the constitution designed to separate church and state when teachers are engaged in private prayer, which was such a misrepresentation of the Kennedy case that Sotomayor took the unusual step of including a photo of what the actual “private prayer” looked like.

Playing constitutional calvinball with individual rights along partisan lines is all too transparent. The underlying arguments can be easily picked apart. Adam Winkler, a UCLA professor who studies the history of gun rights in American skewered the cherry-picked historicism of the court’s decision on New York gun laws:

Most notable is that the Court says it is going to look to history and tradition, but then ignores history and tradition. The Court says that only gun laws which have historical precedent are constitutionally permissible, and then the Court dismisses all of the historical precedents for heavy restrictions on concealed-carry laws as outliers. The Court says that it is going to look to history, but dismisses early English common law as too old. The Court says that it is going to look to history, but dismisses any laws that were adopted after the mid-eighteen-hundreds as too young. The Court says that it is looking to history, but also says that shall-issue permitting is constitutional, even though shall-issue permitting is a twentieth-century invention. So the Court says that it is doing history and tradition analysis, but conveniently ignores any history it doesn’t like.

The court’s historical reasoning on abortion is similarly contestable.

With West Virginia vs. EPA. SCOTUS picked a case where the policy being contested — an Obama era interpretation of the Clear Air Act to regulate power plants — never went into effect, was reversed by the Trump administration, and is not coming back. The constitution specifies that the Supreme Court can only hear “cases or controversies” to limit the capacity of the court to pick and choose its own policy agenda. The fact that it is impossible for plaintiffs to demonstrate harm in a case where no actual policy is in play offered no constraint on the court in this case. (Remember, SCOTUS dismissed a gerrymandering case because voters in a very gerrymandered state were judged unable to show harm, and therefore lacked standing). Why do this? Because SCOTUS wanted undermine the administrative state, and the case provided a means to do so, and it did not feel compelled to show minimal restraint.

You didn’t hear much about the old conservative trope of “activist judges” from the right in the last couple of weeks, even as SCOTUS adopted its new role as policymaker-in-chief. That is because it has become harder to sustain the fiction that vaunted conservative modes of constitutional interpretation, originalism and attention to historical context, are vehicles to constrain activism. Instead, it is increasingly clear they give license to subjective interpretations that rationalize upending the stability of laws and rights.

The judges look at the constitution, into history, and are pleased to find their own values telling them to do what they want. And the rest of us have to live with the consequences.

You can read more posts about the decline of administrative capacity in the archive. Please subscribe if you have not already, and consider sharing.

It is depressingly possible that the Dobbs decision might result in an increase in the court’s perceived legitimacy in the short-run, as more conservative partisans give credit to the court for delivering on a long-sought goal.

The reflexive conservative counter-argument here is that some precedents are bad and need to be overturned. This is why Plessy v. Ferguson, Brown v. Board of Education and Korematsu are so frequently invoked to defend the Dobbs decision. Excluded from this reasoning is an acknowledgment that in that it is one thing to cheer the court overturning precedent to protect against state actions that intruded on individual rights, and quite another to overturn precedent to strip people of rights they have come to rely on.

Even if we accepted this claim at face value, it anchors America to a set of ideas that are very old and almost impossible to change via constitutional amendment. Justice Scalia once noted that fewer than 2% of the population could block a constitutional amendment: “It ought to be hard, but not that hard.” Almost by definition, a country that is practically unable to evolve its institutions is setting the seeds of its own decline.