The Deconstruction of the Administrative State is Proceeding Judiciously

The conservative SCOTUS is set to undermine the battle against climate change

Early in 2017, Stephen Bannon drew a lot of attention when he proposed that the purpose of the Trump administration was “the deconstruction of the administrative state.” In some ways, it was vintage Bannon, and the Trump administration more generally: very quotable, but short on details beyond vague promise to unwind the system of taxes, regulation and associated administrative machinery that evolved during much of the twentieth century.

Photo: Alex Wong

The Trump administration made some progress toward its goals: scientific expertise was sidelined, taxes were cut, troublesome bureaucrats were pushed out of jobs.

But by the end of the Trump administration, it would have been easy to assume that the administrative state had survived, even if a little the worse for wear. Certainly, things will get worse if Trump or a Trump-like candidate — which seems to be the most likely outcome of the next GOP primary — retakes control of the White House. For example, it is entirely plausible that the civil service system will be gutted via a series of loyalty tests imposed by the next Republican President.

But Republicans can fail to win the presidency for a generation and still watch as Bannon’s promise comes to fruition. A conservative judiciary, overseen by 6-3 supermajority on the Supreme Court, characterized by an extreme skepticism of administrative power, stands ready to do the job.

The conservative wing of SCOTUS believes that it is their job to rein in the power of administrative actors, without providing any practical alternative for how large scale administrative action will take place.

Discussions of new judicial theories of the administrative state can sound pretty abstract, so it is helpful to break down what it means in specific policy areas. One example is the recent 5th Circuit decision, Jarkesy v. SEC, where the court deemed unconstitutional the SEC’s primary means to uphold securities laws, the use of administrative hearings. If upheld, the decision not only puts in doubt decades of securities regulations, but also the decisions of any agency using such hearings.

Gutting Climate Change Action by Strangling the Administrative State

An even more dramatic example is a series of cases set to topple the ability of the EPA to address climate change. Coral Davenport of the New York Times offered an exceptionally well-sketched big picture of the stakes, which are, essentially, whether the US will actually be able to do much to limit climate change before it’s too late.

Davenport details the individual cases, but it is perhaps more important to understand the broader political economy behind them. Funders from the oil and gas industries view investments in political and judicial influence as connected means to stop government action. The key players include the Federalist Society, its donors, Republican Attorney Generals ready to advance novel legal arguments, and the judges themselves:

The Republican plaintiffs share many of the same donors behind efforts to nominate and confirm five of the Republicans on the bench — John G. Roberts, Samuel A. Alito Jr., Neil M. Gorsuch, Brett M. Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett. “It’s a pincer move,” said Lisa Graves, executive director of the progressive watchdog group True North Research and a former senior Justice Department official. “They are teeing up the attorneys to bring the litigation before the same judges that they handpicked.” The pattern is repeated in other climate cases filed by the Republican attorneys general and now advancing through the lower courts: The plaintiffs are supported by the same network of conservative donors who helped former President Donald J. Trump place more than 200 federal judges, many now in position to rule on the climate cases in the coming year.

The cases, including West Virginia vs. EPA, seek to restrict the ability of the federal government to act by claiming that traditional notions of Congressional delegation behind such actions are wrong. The end result would be to stop agencies from limiting tailpipe emissions, compel the replacement of fossil fuels for electricity, or consider the economic costs of climate change when evaluating the costs and benefits of new pipelines.

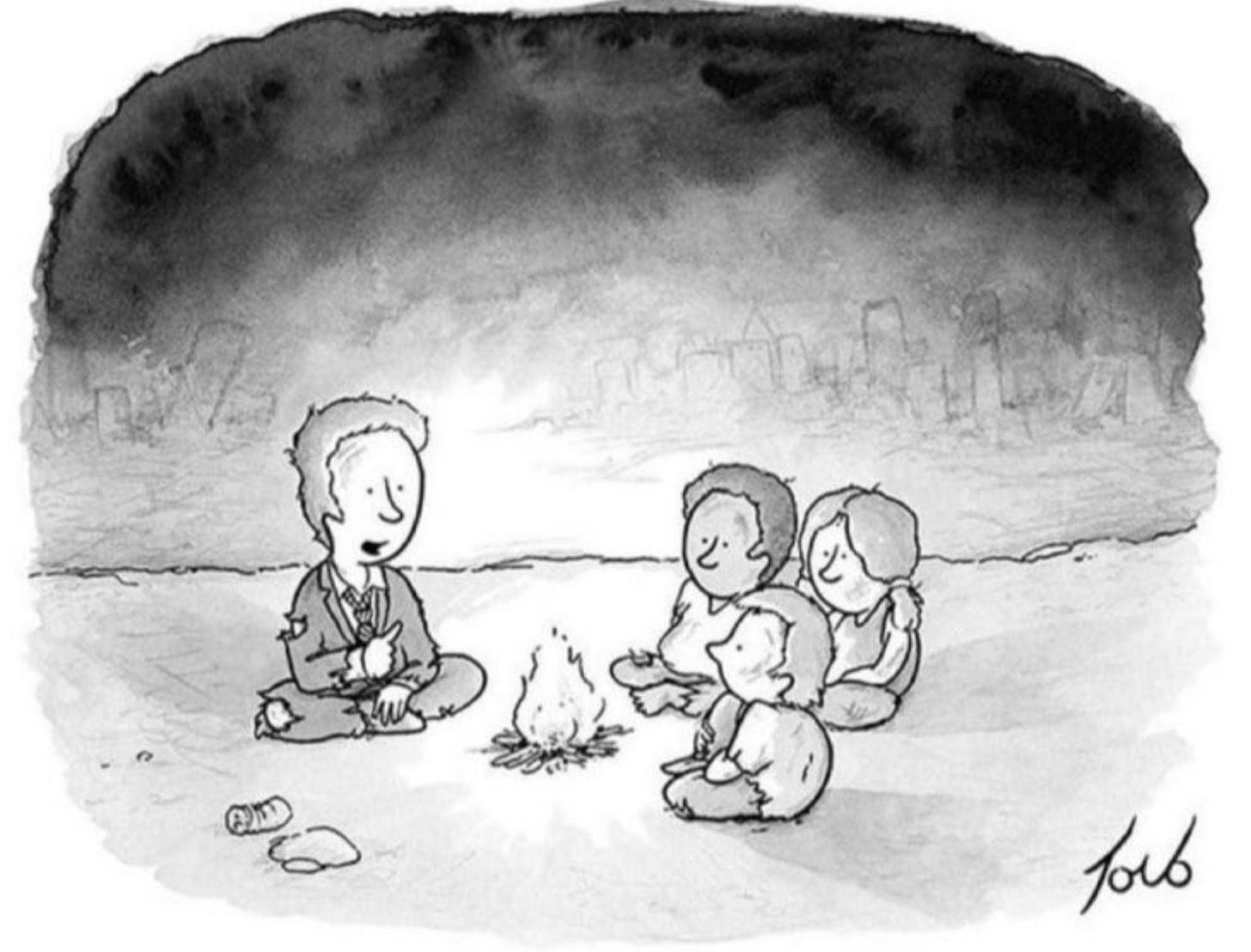

“Yes, the planet got destroyed but for a beautiful moment in time we rolled back the Chevron deference doctrine.”

Since 1984, courts have formalized a long-standing practice of giving deference to administrative actors when the law was unclear, known as the “Chevron deference.” The basic logic, as John Paul Stevens wrote in an unanimous ruling was that “Judges are not experts in the field and are not part of either political branch of the government.”

At the time, Chevron was uncontroversial, and became the basis for thousands of decisions on how the government manages the most basic aspect of our lives, such as health, the environment, our workplace, and finances. In 2018, Stevens would say it made “a lot of sense to give the people in the government who have the most specialized knowledge of the particular area a preference that, when in doubt, you go along with their view.”

But support for Chevron has eroded amongst conservatives, as concerns of the risk of the administrative state have grown. In 2013, Chief Justice Roberts warned that “the danger posed by the growing power of the administrative state cannot be dismissed.” Associate Justice Gorsuch wrote that Chevron allowed “executive bureaucracies to swallow huge amounts of core judicial and legislative power.” Thomas has frequently bemoaned that agencies should not be give quasi-judicial powers, saying that Chevron: “wrests from Courts the ultimate interpretative authority to 'say what the law is' and hands it over to the Executive.” The ability of conservative judges to act dramatically on these concerns has been unleashed by the super-majority created by a President who raged against the “deep state.”

Davenport describes how Don McGahn, the Federalist Society member who vetted Trump’s Supreme Court nominees, focused on Chevron in their selection processes:

“Well, it’s not a coincidence,” he said. “It’s part of a larger, larger plan, I suppose…There is a coherent plan here where, actually, the judicial selection and the deregulatory efforts are really the flip side of the same coin.”

The consequences for fighting climate change cannot be overstated. While President Biden proposed an aggressive climate agenda, in practical terms he has been left only with executive action, which some of the lawsuits seek to pre-empt. As we debate about whether the US can do big things, the biggest thing is surely whether it can play a role in keeping the planet habitable, especially when it has played an outsize role in contributing to climate change. How do we explain to the rest of the world that there is nothing to be done, because a small group of judicial actors have decided to reverse their interpretations of the powers of administrative actors?

The Judicial State is Not a Real Alternative

Debates about the administrative sate and its capacities, or even about what is possible in our contemporary politics, are very incomplete if they do not consider the impact of a super-majority SCOTUS with fixed views on how the state should operate. They are the ball game. The simple answer to the question of “why is American administrative capacity in decline?” may be that in certain policy domains at least, political actors have put in place a judiciary that wants it that way.

There is one minor problem with deconstructing the administrative state: it is wildly impractical, entirely unfit for the workings of a modern state, with no practical alternative on the table.1

The current iteration of our state reflects nearly a century of accommodation, practice and incremental change that emerged to facilitate the emergence of the modern society, which evolved dramatically between the end of World War I and World War II as people demanded new services and standards from its elected representatives. Congress realized it could not write laws for every eventuality, and could not closely monitor everything agencies did, and so started to delegate more authority to administrative actors, but imbuing them with legislative values (think the Administrative Procedures Act’s requirements for rule-making) and allowing judicial oversight.

The ability of administrative actors to use state power is exceptionally constrained — indeed, an alternative theory of declining administrative capacity is that they are too constrained, taking years to issue new rules. Congress has proven itself to be quite adept at exerting different types of controls over administrative power. If the US administrative state is leviathan, it is very much leviathan on a leash.

Elected officials have therefore given careful attention of how to balance administrative power with democratic values. By contrast, the question of how to run a modern administrative state without delegating to administrative actors is unanswered. Congress writing more detailed regulations is a recipe for rent-seeking, overly detailed and inflexible policy. The courts are not designed to provide scientific or other forms of administrative expertise. Because of this, there may be some practical limits to how the courts roll back administrative expertise. For example, SCOTUS recently decided not to question Chevron deference in American Hospital Association v. Becerra, perhaps deciding that the incredibly complex procedures over Medicare reimbursement rates was not something that they, after all, needed to weigh in on.

While much of the fulminating about the administrative state centers on “unelected bureaucrats” the de-facto alternative proposed by the conservative wing of the court is that unelected and generally unrepresentative cohort of judges, untethered by administrative requirements to ground their rules in scientific evidence or democratic responsiveness, should have veto power over regulation.

While our politics are closely divided, SCOTUS is not. Its unity of purpose makes it the most powerful policymaking actor in contemporary America. Sadly, this remarkable power coincides with a worldview that the government should not to respond to the most existential of challenges, condemning untold billions to grimmer lives.

If you enjoyed this, chances are you will enjoy this previous piece on declining administrative capacity, plus the archive. Please subscribe if you have not already, and consider sharing.

Full disclosure: I am not a lawyer. I am a social scientist who studies public administration. The arguments I am making are not legal ones, but about whether we can still govern. Hence the name of the blog. I will note a certain mystification at how very serious lawyers can assert that their theories of interpretation can be both objectively correct, while also relatively novel and subject to wide disagreement, but perfectly consistent with the interests of the donors who underwrote the legal society they joined while in college. I am sure my concerns reflect some easily-dismissed legal ethos, such as the idea that the constitution should be interpreted consistent with the world around it, rather than vice-versa.

Good. More of this needed.

With respect, deference to administrative action is not "traditional" - it pretty clearly traces to the rise of the progressive political movements in the first decades of the 20th century that sought to implement professionalized and, to use the parlance of the time, "scientific" administration in the first place. Moreover, the idea that administrative agencies should be little, subject-matter specific governments in miniature, with their own executive (enforcement), legislative (rulemaking/policy-setting), and judicial (adjudicatory) bodies and powers, all under the nominal command of the executive branch and separate from either the broader legislative or judicial bodies within the existing constitutional structure, is also not "traditional" at all, and certainly not uncontested.

There is nothing, for example, to stop Congress from appropriating itself sufficient money to form a permanent advisory body to investigate and report on matters of environmental concern, and suggest draft legislation. Similarly, though the constitution does state that federal courts are to have the "judicial power", the structure of the federal courts is not specified beyond a few details about the Supreme Court. There's nothing to stop Congress from massively expanding the number of judges to facilitate faster claim-processing, clarifying the scope and reach of lower-court judicial rulings to avoid the problem of obtaining nationwide injunctions through forum-shopping, or creating specialized courts for different types of expertise (though this type of "jurisdiction stripping" is highly controversial - it is far too easy for mono-purpose courts where one agency is involved in every case but the other party comes in cold to turn into kangaroo courts).