How to think about administrative burdens embedded in new voting laws

Worrying signs from Texas

A while back Nate Cohn from the New York Times argued that the wave of more restrictive voting laws in red states might not matter much to turnout. Here is the lede from his piece:

There’s nothing unusual about exaggeration in politics. But when it comes to the debate over voting rights, something more than exaggeration is going on.

There’s a real — and bipartisan — misunderstanding about whether making it easier or harder to vote, especially by mail, has a significant effect on turnout or electoral outcomes. The evidence suggests it does not.

Cohn took some pushback, partly on the grounds that he was inattentive to the intent of Republcian lawmakers to use election laws to benefit their party. But on empirical grounds he made a reasonable case, drawing on social science research about voting, including a paper of mine, to make the point that election laws often do not have big effects on turnout.

But I worry that the implementation of the latest round of election laws may have larger effects than we have seen in the past for three reasons.

First, because of the evolution of convenience voting laws, like vote by mail (VBM) or early voting, social scientists tend to look at the effects of their introduction, but not their removal. We also know that voting is a habit, and so we should be concerned by changes that disrupt the habit of voting rather than allow new options to vote.

Second, the new laws demand non-intuitive changes that many voters, and marginal voters in particular, will not be aware of. This lack of awareness could be very costly.

Third, the costs of voting are often partly offset by third parties and public officials, who help people to register and avoid errors. New voting laws that limit the ability to provide help leaves voters on their own.

Early evidence from Texas: small hassles are a big deal

Spring elections and the warnings of local election officials are our canary in the coal-mine for the effects of new laws. And reports from Texas about the effect of its new absentee voting law are especially worrisome.

One provision of the law is that VBM voters must write down an ID number on their ballot. This could be the last four digits of their Social Security Number, or a Texas ID number, which most likely comes from a drivers license, but it must match the ID number on their voter registration records.

The problem is that voters are not used to writing down such a number. Actual human beings, with real lives, do not pay close attention to new administrative changes, especially ones so subtle. This is a basic reality of policy implementation.1

Some may be vaguely aware of the change, are unsure how to comply with it. Some might not know which ID number is on their voter registration, or have never provided one to the state. Some might attempt to comply, but make an error.

Travis County Clerk Dana DeBeauvoir: This is all brand new…These are new obstacles for voters. They have never had to deal with this kind of problem in the past.

The pull of habit is strong, and so many voters will complete the ballot as they have done in the past. Without an election official on hand to correct them, they violate the new state law and their votes are tossed.

The early indications are that the new law is causing an extraordinary number of defective ballots.

Local election officials in Texas are reporting that 25-40% of mail ballots in some counties are not being counted because they violate the new requirement to have an ID number.

Texas is an example of new policies imposing new administrative burdens both on the public and the local election official who face new and more complex tasks — not just checking IDs, but also outreach, and helping people cure their defect ballot. Election officials can, if they have the time, inclination and resources, reach out and help the voter to remedy the error. Offices with fewer resources are less likely to do so.

Even if election officials do reach out, the voter now has to vote a second time. Why bother? Maybe it feels like they don’t want you to vote.

“It feels like people were just sitting up late at night thinking up ways to discourage people from voting” - Texas retiree, Jo Nell Yarbrough

While state officials expressed surprise when these problems emerged in January, the outcome was entirely predictable. Indeed, it was predicted. James Slattery, senior staff attorney with the Texas Civil Rights Project told lawmakers when the ID provision was being considered: "It is easy to see the needless chaos and mass disenfranchisement that requiring this matching process will create."

Traditional studies of voting don’t provide much help in understanding the effect of some new voting practices

In Texas, VBM is restricted to those aged 65 and over, those with disabilities, or who will be absent from the state, in jail, or due to give birth. It’s not clear to me that there is any partisan advantage to Republicans with this change, since the largest group affected, older voters, tend to skew Republican. Parties are sometimes poor predictors of how election laws would affect them.

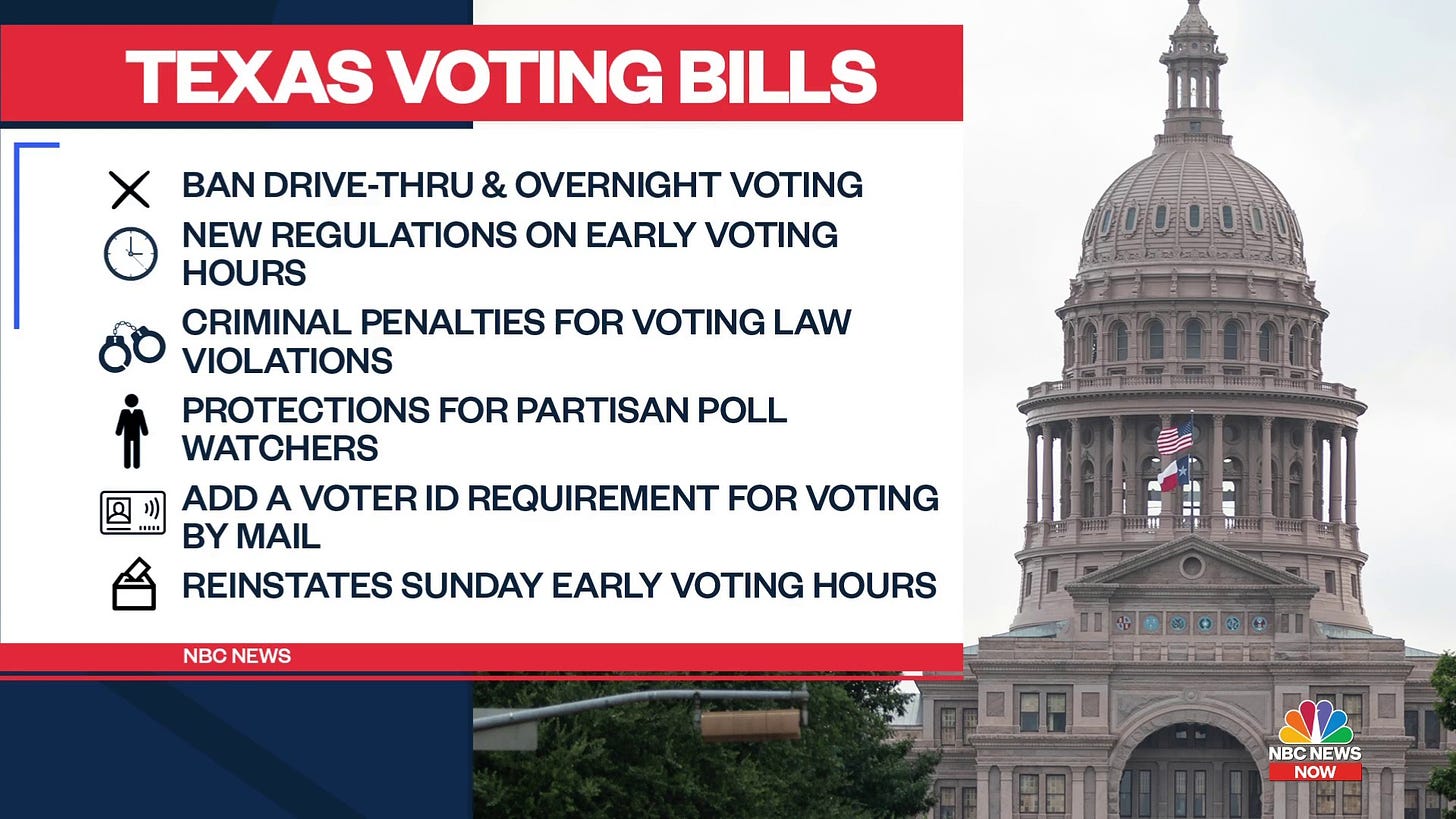

But we should read the laws as part of a broader philosophy that seeks to make it more costly to vote. The Texas law targeted initiatives used in Democratic counties during the pandemic to make voting easier, such as drive-thru voting and extended early voting. Georgia laws similarly target VBM laws that Republicans had once championed, but opposed once Democrats were viewed as using them to increase turnout.

Another part of the Texas law makes it harder for election officials and third parties to help people to vote. Third parties like the League of Women Voters face criminal liability if they provide incorrect voter registration information, while election officials are barred from pro-actively distributing VBM ballots that people are legally entitled to. The latter provision is now subject to a legal dispute, but it certainly has a chilling effect on outreach efforts. Texas has also come under criticism for making new voter registration policies unclear, and not providing new voter registration cards to third parties to help people register because, in the year 2022, it does not have enough paper for its paper-based voter registration system. (It is only one of ten states still relying on such a system).

The thing is, I don’t know of prior research that has tried to model these types of changes on voting. There are studies about the effects of VBM, which show that it increases turnout and benefits both parties. But we know much less about what happens when policymakers pour sludge into an existing voting process. VBM still exists in Texas. It has just become a lot harder to use.

Other domains of research, from behavioral science and administrative burden, suggests that seemingly small administrative requirements can have large effects. This work also points to the importance of help from officials and third parties in managing those hassles. My research interests in those areas makes me much more concerned about the Texas law than my research on election laws.

In Texas, the catastrophic number of VBM errors we are seeing now will decline. Voters will learn more about the new law. But it will likely lead to some permanent increase in defective ballots, and less interest in using VBM. In the meantime, some eligible voters will see their votes tossed for no good reason. It probably won’t have a partisan effect on turnout. But it imposes new and unnecessary costs on both voters and administrators. And we should be paying attention to those costs.

Focus on burdens, not turnout

Our standard for evaluating new voting laws and administrative practices should not be “do they reduce turnout?” or “will they benefit one party?” but rather “do new laws impose pointless burdens on voting?” and “are those burdens targeted toward some groups more than others?”

A good law should create benefits for the public and avoid unnecessary costs. Many new voting laws are restricting clear benefits to voter — convenience and access — while imposing pointless new costs upon them. Some of these laws, such as Georgia’s, deliberately target those costs on urban voters, because they tend to vote Democratic.

Those are bad laws and administrative actions, working against the best interests of the citizenry to access a fundamental right, and burdening some more than others. They rely on administrative burdens that are no less consequential than more visible changes in election laws.

That is not, of course, the stated views of the proponents of such laws, who publicly emphasize election integrity and voter confidence, even if they privately hope to help their party by tilting the playing field. But to prove election integrity, we need evidence of systematic fraud, and we simply don’t have that for the very good reason that people don’t want to expose themselves to severe legal risk for engaging in fraud.

A leading proponent of the Texas law, State Rep. Briscoe Cain (R), justified it by saying: “Texans deserve to have confidence in the electoral system.” It is hard to take this seriously. Voter confidence has dropped, in large part because Trump and followers like Cain have lied to the public, acting as if a free and fair election was beset with fraud. Indeed, Cain personally took part in challenging the 2020 election, helping a Pennsylvania lawsuit that a federal judge tossed while noting it featured “strained legal arguments without merit and speculative accusations” that were “unsupported by evidence.”

If voter confidence is important, making the process of voting a baffling and frustrating Kafkaesque experience where their vote may or may not count is hardly the solution. Instead, governments should have a bias toward encouraging people to vote, and making the process simple, accessible and respectful. Right now, states like Texas are doing the opposite.

If you found this post useful, please check out previous posts about administrative burdens, election officials, consider subscribing if you have not done so, and share with others!

The Epic Journey of the American Voter from Dana Chisnell and the team at Center for Civic Design (2017) shows how some of this administrative burden comes to life for voters in this useful contrast between the "happy path" and the "burdened path": https://civicdesign.org/the-epic-journey-of-american-voters/