Who won on January 6th? It wasn’t the people who put themselves in legal jeopardy by invading the Capitol. Democrats are no better off than before, having failed to use January 6th as an issue to consolidate support among the public or advance new protections of voting rights.

The winners of January 6th were the political actors who encouraged the attack, most clearly President Trump and his close circle of loyalists.

The winners of January 6th are unlikely to face any legal punishment for their actions. They have succeeded in persuading their supporters that they were the victim of a great injustice—a stolen election!—and the only reasonable response is to take control of future elections. Their central claim has gained widespread acceptance within the Republican Party.

A year on, American democracy is less rather than more secure than it was when the insurrectionists attacked the Capitol. The GOP brand has recovered even though the party continues to act as if the Big Lie that motivated the January 6th attack represents an accurate account of the last election.

The political actors that have learned the most from an attempted coup in 2020, and are most aggressively putting those lessons into practice, are the coup plotters rather than the defenders of democracy.

Recent changes in election administration reflect the growing influence, rather than a refutation, of those who denied the outcome of the 2020 election. The threats being made to members of Congress on January 6th are now being directed toward local election officials. Consider the following:

6 in 10 Republicans say that believing that Trump won the election is important to what being a Republican means to them

1 in 3 election officials say they felt unsafe because of their job; 1 in 6 reported threats

1 in 8 threats made to election officials that Reuters reviewed passed the threshold of prosecutable threats

Zero arrests have been made

Different strategies, one goal

The Big Lie provides the root justification for four overlapping election strategies:

Passing legislation that increased the costs of voting in 19 states in 2021

Moving power to determine election administration and outcomes to legislatures more likely to overturn the results

Taking control of election official positions

Intimidating election officials who have resisted the Big Lie

Each of these four strategies start with the false claim that the 2020 election was deeply flawed. While legislation that makes voting more onerous seeks to shape who votes, the latter three strategies prefer to take direct control of election administration. The actors involved might or might not truly believe that Trump had the election stolen from him, but they are acting to ensure that the same outcome will not be repeated.

I will focus on the last two options: taking control of election official positions and intimidating election officials. I started doing research on election administration almost 20 years ago. Back then, Professor Carol Silva and I ran the first national survey of local election officials for the Congressional Research Service. They seemed like an understudied but important group. We used terms like “the administrators of democracy.” Now I sit on the advisory board for a new national survey of election officials. Some of our original survey questions are still being used. But we’ve also needed to come up with new questions about threats and intimidation, questions that would have been unthinkable 20, or even 10 years ago. Its not that these earlier times were devoid of polarization. But the rise of the Tea Party in 2010 or the intense anger in the aftermath of the 2000 election did not translate into election officials facing systematic intimidation, or competition for their jobs, from those who fundamentally doubt American democracy.1

Taking control

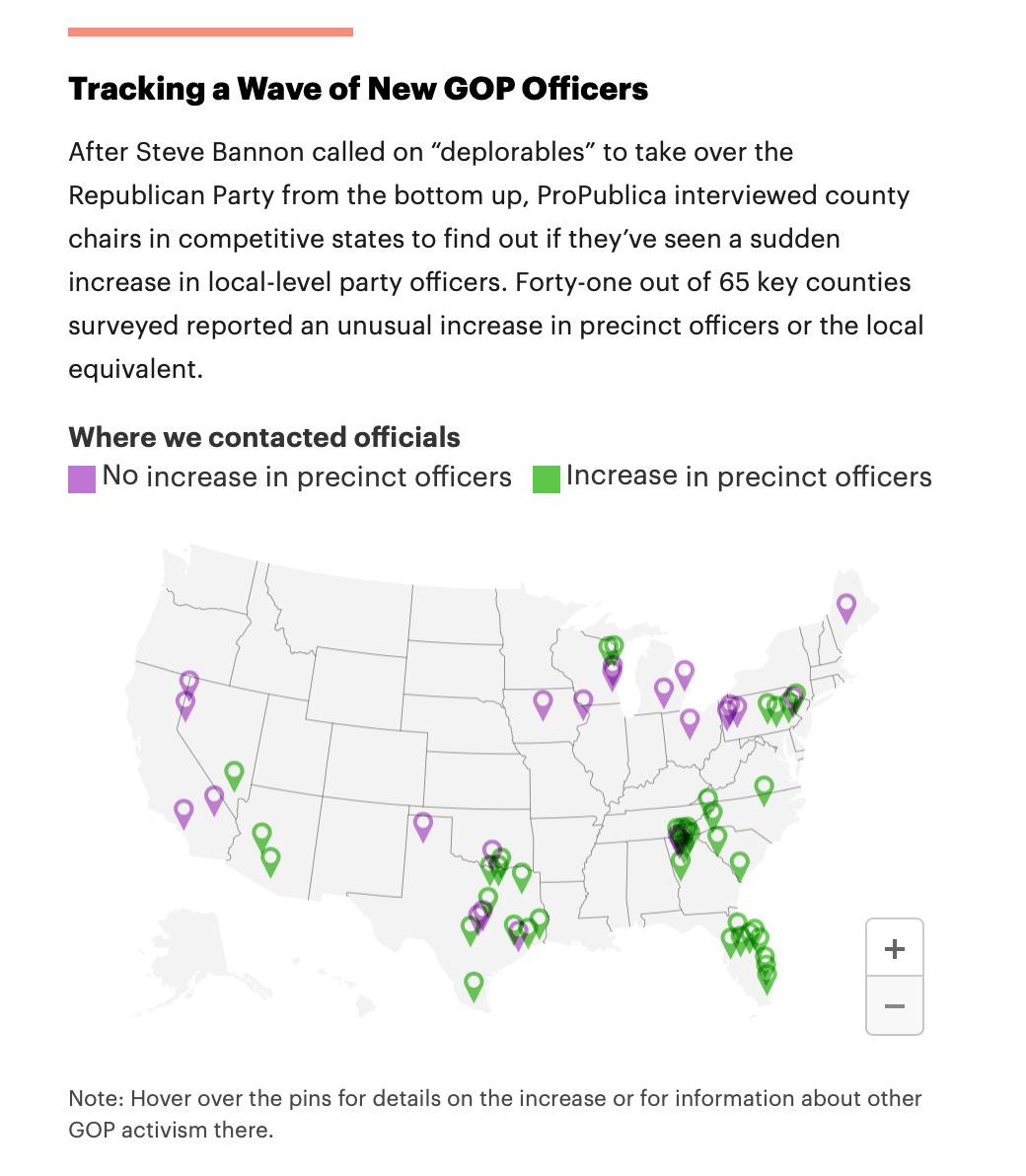

The same voices who that have pushed the Big Lie are urging their supporters to act on it by directly taking control of posts that will determine elections. This is true for the most high profile election administration positions: at least 15 Republican candidates running for Secretary of State positions in 2022 have cast doubt on Biden’s win. It’s also true for less visible and less contested positions. Steve Bannon, who encouraged the insurrection on January 6th, pivoted to a “precinct strategy” in the aftermath of its failure, encouraging followers to “take this back village by village . . . precinct by precinct.” By doing so, he declared, “We're taking over the Republican Party . . .We're taking over all the elections.”

The precinct strategy is hard to observe and measure. But it has been warmly embraced on conservative and QAnon media and seems to have led to a surge of action on the ground level.

Why does this matter? In many places, local party organizations pick poll workers and the local boards that oversee elections. Gain control of the local level, and you gain significantly more control of the administrative machinery of elections.

The precinct strategy has made the front lines of the Republican Party less committed to democracy, and more committed to anti-democratic conspiracy theories. A GOP County Chairman was upfront and enthusiastic about the motivation of the new members: “They feel President Trump was rightfully elected president and it was taken from him. They feel their involvement in upcoming elections will prevent something like that from happening again.”

For example, key Michigan election canvassers who certified the results in 2020 have been removed and replaced by officials who say they would not have honored the will of the voters. Stephen Lindemuth, a January 6th rally attendee, won an election for a position in Pennsylvania that gives him oversight of local balloting procedures. These sorts of positions are largely thankless roles, and often uncontested as a result. But a motivated Big Lie base means they are more likely to be occupied by people who have declared their lack of faith in the existing machinery of voting. Lindemuth is not unusual. Other local election candidates in Pennsylvania supported Trump’s Big Lie claims, and were able to win uncontested elections.

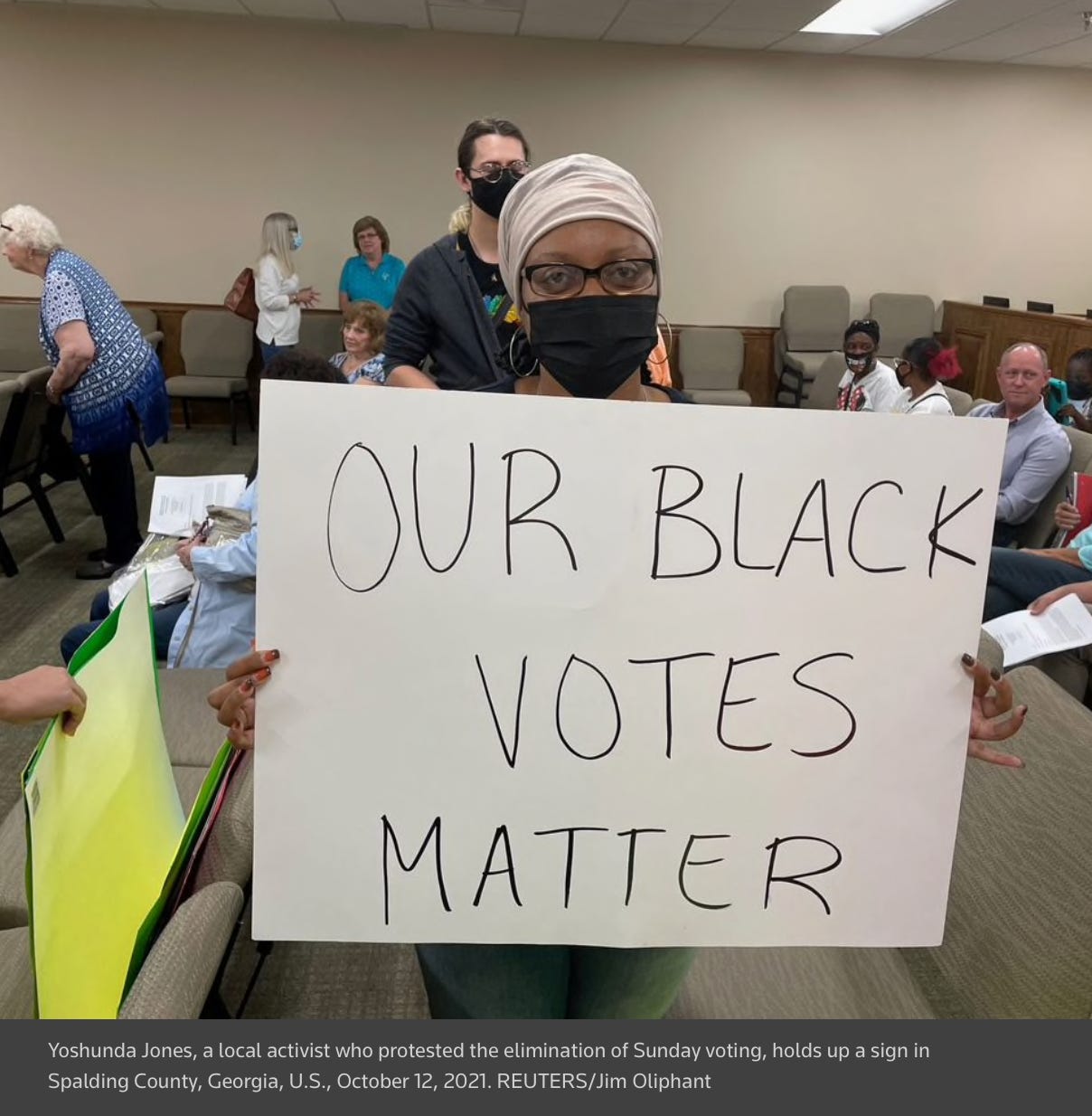

It would be a mistake to assume that the control strategy is being implemented only via bottom-up processes. In Georgia, state legislation gave the Republican majority the power to change the make-up of local election boards. This power was used to target majority Black election boards. For example, Spalding County’s majority Black board and Black election supervisor was replaced, with a new chair who had endorsed the Big Lie. After Black voter turnout jumped in 2020, Spalding County had been the subject of fraud accusations, to the point election officials needed police escorts. Departing members of the board cited personal threats from Trump supporters: “I have never been afraid in this town, but I am now” said one. The new Republican majority ended Sunday voting, a strategy widely assumed to benefit Black voters as churches run “Souls to the Polls” get-out-the-vote efforts.

Intimidation

Undemocratic regimes maintain control via a mixture of formal powers and informal threats of violence. The January 6th rally attendees were encouraged to go to the Capitol to intimidate Pence and Congress as part of a series of actions that Trump insiders saw as a means to overturn the election.

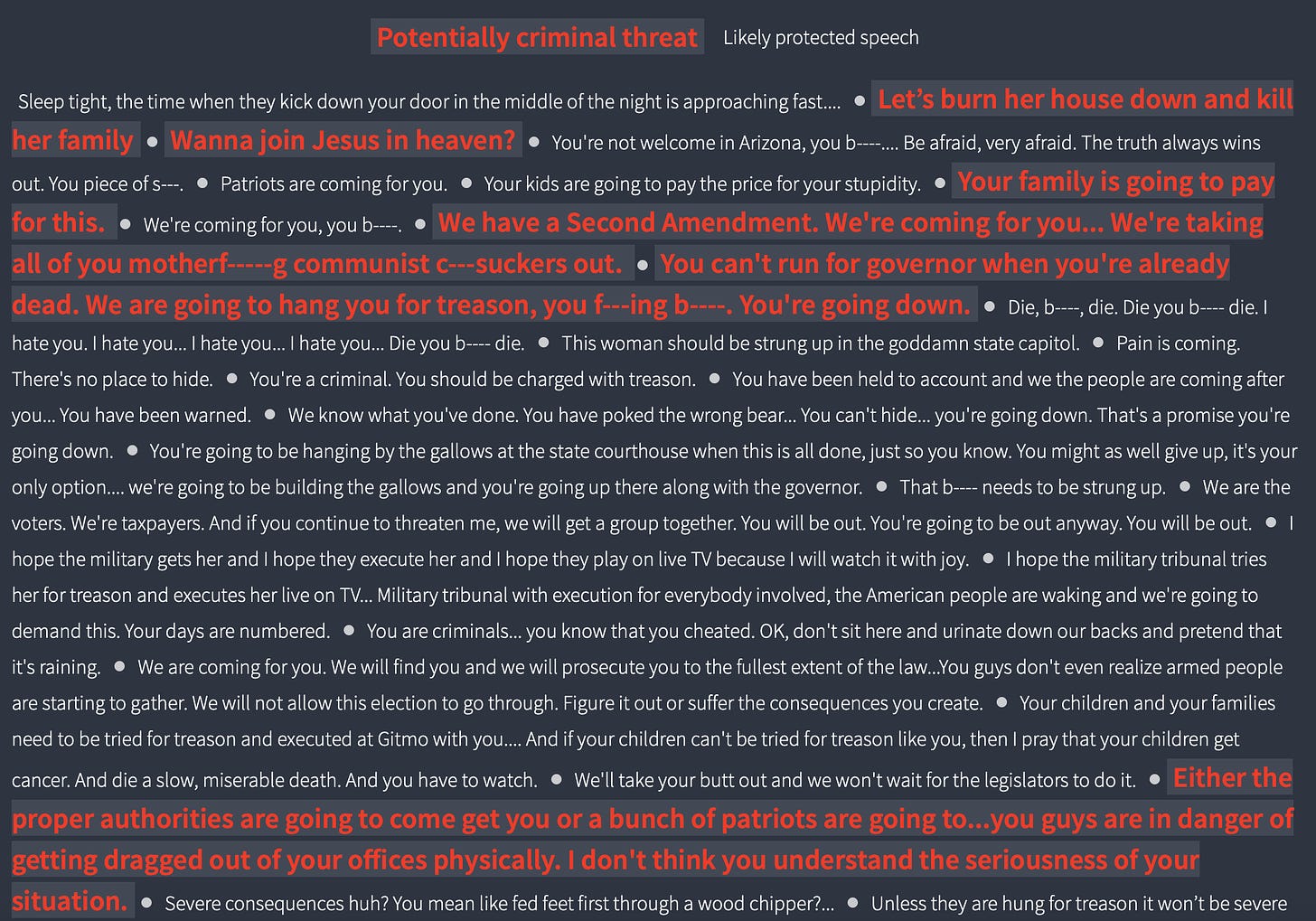

This pattern of intimidation is also being applied to local election officials. Reuters documented 850 threats to election officials in the aftermath of 2020. This is an undercount, but even so, the scale of the threats is extraordinary.

A wide-scale, new and systemic pattern of intimidation of the people charged with ensuring we can use our most basic political rights should be considered a national emergency.

While the Department of Justice has set up a task force to investigate threats, it has not resulted in any arrests. Much of the language embedded in these threats are likely protected speech. (Reuters provides examples that distinguish between protected and likely criminal speech below). But that is little consolation to the election officials who may reasonably feel their lives are being threatened.

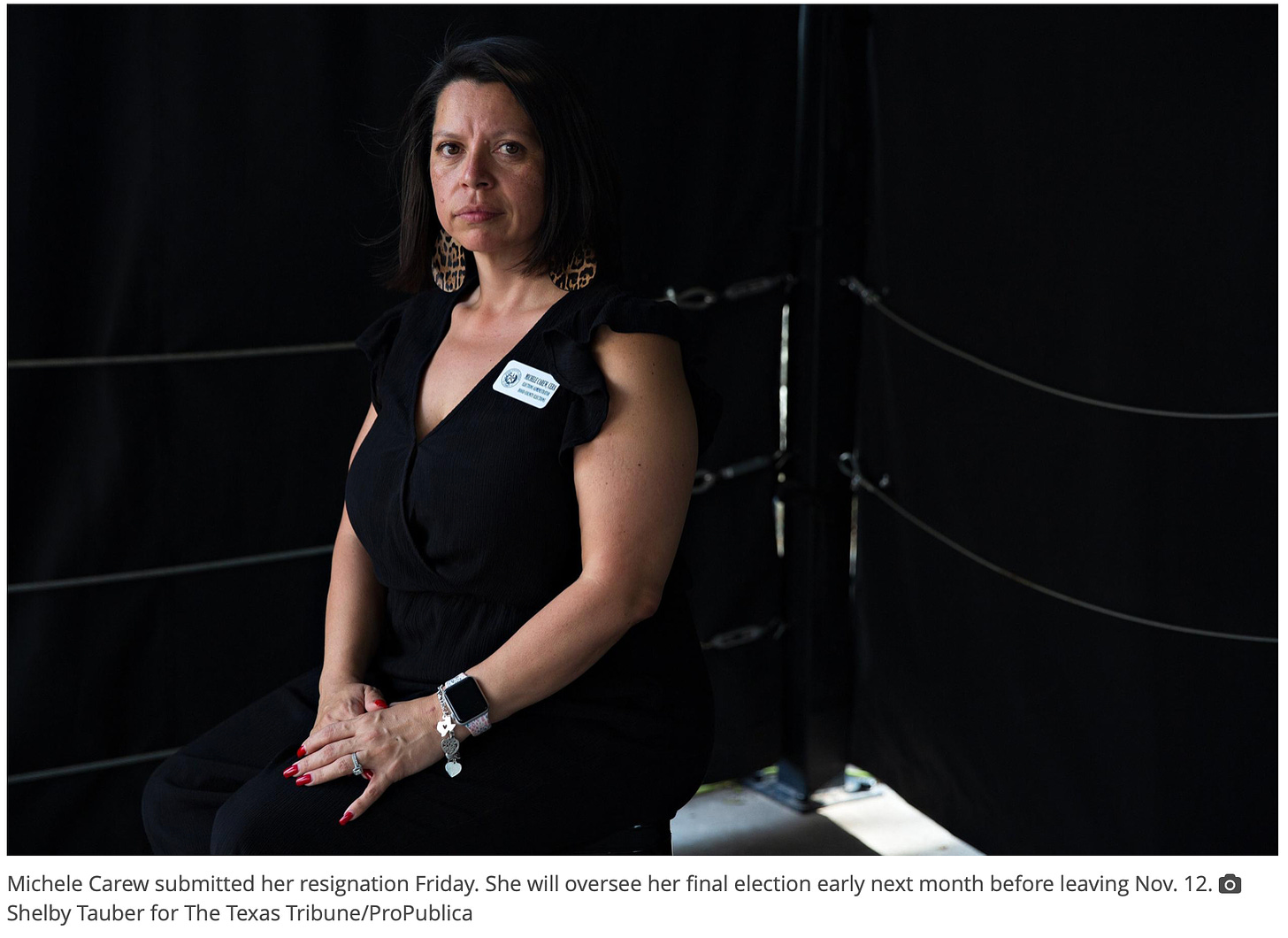

It’s important to understand the blurring of the lines between intimidation and perfectly legal campaigns to remove election officials described above. In Hood County in Texas, Michele Carew resigned after a virulent months-long campaign where the local Republican Party aligned with online activists to suggest she an enemy of free and fair elections. Trump won the county with 81% of the vote, but Carew was subject to attack for failings such as not allowing pro-Trump media sit in on election official training and seeking grants from private foundations to support the costs of running elections. Her critics sought to move her duties to a Republican county clerk who endorsed the Big Lie.

“When I started out, election administrators were appreciated and highly respected. Now we are made out to be the bad guys.” - Michele Carew, Texas election official

The same actors that incited the attack on the Capitol are encouraging the intimidation of election officials. For example, false Gateway Pundit stories alleging election officials engaged in fraud led to more than two-dozen of these officials facing over 100 threats. After one story alleging that a Wisconsin clerk had switched votes, which was shared by Eric Trump on twitter, the local official needed police protection.

Two officials sued Gateway Pundit for defamation. Trump’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, had attacked both, Ruby Freeman and her daughter Shaye Moss as “crooks” who “obviously” stole votes. A Georgia Congressman Congressman Jody Hice tweeted out: “Say it with me... F R A U D.” (Hice is now a Trump-endorsed candidate for Secretary of State). Trump repeatedly mentioned Freeman in calls to the Georgia Secretary of State calling her “a professional vote scammer and hustler.” When the transcript of the call went public, the threats elevated

Freeman was a temporary election worker, earning $16 an hour, whose life was turned upside down by the attacks. In a series of 911 calls, she detailed how she was receiving “threats and phone calls and racial slurs.” Strangers were turning up at her home: “Somebody was banging on my door, and now somebody is banging on the door again.” In a police incident report, Freeman reported threats via about “300 emails, 75 text messages, a large amount of phone calls and multiple Facebook posts.” Her daughter Moss fled her home for two months at the recommendation of the FBI after she was doxxed. As late as July, Moss found that pictures of her car and license had been posted online, and friends and family were still receiving threatening messages. Gateway Pundit repeated the false allegations again in August, setting off a fresh wave of threats.

Anonymous emails or voicemails are not the only types of intimidation. Other take a more formal means. Some state election bills create new legal risks if local election officials try too much to increase turnout. Another mechanism of intimidation comes via election audits. To be clear, all elections face audit requirements. Here, I’m talking about special audits ordered by partisan actors, and undertaken by people without election administration expertise that provide a means of legal harassment of election officials.

In Wisconsin, for example, the state legislature empowered Michael Gableman, a former State Supreme Court judge to oversee an election audit (in addition to the one undertook by the Wisconsin Election Commission, a legislative committee, and the Legislative Audit Bureau). Gableman has run a bizarre operation at odds with any semblance of public accountability, hiding his employees, sharing materials with conspiracy theorists like Mike Lindell and an office with a law firm that sought to reverse the election outcome in Wisconsin. Gableman has threatened to jail election officials—typically in urban centers that leaned Democratic—that do not co-operate with him. At the same time, other members of the Republican Party have threatened to dismantle the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Committee (as they previously did with its nonpartisan predecessor, while firing senior election officials). In short, election officials seen as unfriendly to the Republican Party face not just political pressure but also the risk of legal troubles and the loss of their jobs.

Implications for our democracy

The Republican Party cannot move past the Big Lie because Trump, its undisputed leader, refuses to do so. Polling has consistently found that significant majorities of Republicans believe Trump’s false account, giving him the leverage over Republican officials he needs to subvert election administration. This subversion creates both short-term risks and long-term damage.

Capture of election officials by radicals makes democratic backsliding more likely

The 2020 election was not especially close. In many ways it was the mirror image of the 2016 election Trump characterized as a landslide. Nevertheless, Republicans believed that they could overturn the result with a few key states by claiming fraud. Barton Gellman’s Trump’s Next Coup Has Already Begun in The Atlantic suggests that those encouraging the insurrection saw it as an delaying tactic in order to give time for Republican-controlled legislatures to revisit their decisions on the electors they sent to Congress. Republican leadership in Pennsylvania had signaled a willingness to do so, feeding the hope that others states might follow.

Trump’s plan was stymied by election officials who resisted the fraud narrative. This reveals their importance for election subversion.

Election officials don’t have to overturn the elections themselves—they merely have to create a pretext that makes it more respectable for state legislatures to do so.

Imagine if election officials in Georgia like Brad Raffensperger or Gabriel Sterling had ceded to Trump’s demands, and declared that they harbored grave doubts about how certain localities had run the election or counted votes. This would give the state legislature all the permission it needed to step in and determine the outcome of the election.

Imagine that in 2024, a set of election officials pro-actively raise doubts about the integrity of the elections, or engage in dysfunctional behaviors themselves, well ahead of the legislative decision to choose electors. Imagine that state Republicans have been primed to seek just such doubts as a premise to wrest control of the outcome of the vote from the voters. You don’t have to imagine very hard, because they people needed to turn this possibility into a reality are actively seeking to control key positions.

Running elections is hard, it needs competent people

The US largely devolves running our elections to local government. One thing I learned from studying election administration is that it’s hard. The stakes are high, administrators have to deal with federal, state and local policies, rely on temp workers and volunteers, and almost always without enough resources. There are many ways it can go wrong, and no do-overs. Experience and competence matter.

People who sign up to be election officials did not sign up to live in terror. Intimidation effectively increases the costs of their job. A skilled official who doesn’t want the hassle of midnight phone calls or threats to their family will be more likely bow out. Those who are interested in the job for other reasons—such as the opportunity to stamp their preferences on the election outcome—will be more likely to replace them.

Even if the there is no crisis in 2024, even if a particular local official does not shape a national outcome, a dynamic where professionals make way for hacks is a bad thing. Local election officials have real capacity to shape the electorate in numerous ways. This includes the number and accessibility of polling locations, how registration rolls are maintained, how helpful they are in registering voters and whether they encourage turnout. In research with Barry Burden, Ken Mayer, David Canon and Stephane Lavertu, we discovered that appointed local election officials tended to oversee lower turnout in areas where their political ideology differed from that of the public they served—specifically, more conservative officials tended to oversee lower turnout if they had a more liberal constituency. This raises the concern that election officials do more than validate the results—they also shape who votes.

There is a real crisis of legitimacy, and its going to get worse

Currently, a majority of Republicans believe that the election of 2020 was stolen from them. That is very, very bad for democracy. The 2020 election was remarkably well-run under difficult, in large part thanks to election officials who resisted sometimes extraordinary pressure to manufacture a different outcome. Conspiracy theories have been debunked time and again. But the Big Lie continues to poison our democracy.

Democrats currently have fewer doubts than Republicans. Their complaints are largely centered on policies that make it harder to vote. But imagine if the 2022 and 2024 elections feature stories of election officials conspiring to throw out legitimate votes in Democratic-leaning cities. Or legislatures overturning results based on specious claims of fraud. Democrats will have much more reason to believe that election administration and outcomes are illegitimate.

The world that Trump warns of—full of untrustworthy election officials, driven by partisan goals rather than the rule of law or a duty to the public—is becoming closer to a reality because of his actions. US democracy is not perfect by any means, but massive declines in faith in the outcome of elections among supporters of both parties, driven by the lies of one particular candidate, is a catastrophe.

What to do

The standard caveat to fretting about democratic backsliding applies: the most likely outcome is relatively normal electoral outcomes. But risk is not just about probability, it is also about the consequences of a particular outcome. We should do everything to reduce a low-probability but catastrophic event, and we should be alarmed even if it becomes slightly more likely.

There are some partial fixes to the risks I’ve identified. But proposed bills that address fundamental problems such as gerrymandering and voting rights are unlikely to pass as long as Republicans maintain unified opposition. Fixing the Electoral Count Act of 1887 to remove some ambiguities that coup plotters sought to exploit would be good, but would not stop state legislatures from ignoring the will of their voters. In the same way that January 6th insurrectionists are facing legal consequences, the Department of Justice and local law enforcement need to respond to actual threats against election officials that go beyond protected speech.

But my sense is that the main problem is not a lack of solutions, but a lack of urgency. It is only a slight exaggeration to invoke Yeats: the best lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity. The people who are acting with urgency are those who driven by false and anti-democratic beliefs. But even if Democrats can be persuaded to become more engaged on these issues—willing to run candidates for key positions to rebut the precinct strategy for example—this does not solve the problem for deep-red or gerrymandered states.

People assume that political elites will make sure democracy works. But if this responsibility is borne only by one political party in a two-party system, the system is doomed. Republican elites need to push back against the Big Lie, choosing democracy over Trump. Such a stand will mean significant political costs to them, but it’s hard to see how the Republican Party can claim the mantle as a pro-democracy entity otherwise.

If you found this post useful, please check out this piece about the attack on expertise in education, consider subscribing if you have not done so, and share with others!

One can make the case that the 2000 election was one where the decisions of local election officials in Florida did actually determine the outcome of the election. In addition to the faulty ballot design in more liberal counties, Florida’s felon disenfranchisement law was used to justify an aggressive purge of the voting rolls of former felons. The purge removed an estimated 12,000 non-felons, disproportionately Black voters, undermining their participation in an election that gave George W. Bush the Presidency by a margin of 537 votes. Republican election officials were more likely than Democrats to purge such voters.