Administrative Burdens Are Bad for Your Health

New research points to the way that burdens take our time, increase stress and lead to foregone care

Congratulations on your new job. You have received no specialized training, though it requires specialized knowledge. How well you perform could be the difference between avoiding bankruptcy or whether you get essential care.

You are your own health care administrator. You got this job simply by being American, or at least one of the lucky ones with access to health insurance. Perks of the job include confusion about which insurance programs to sign up for, managing disputes between health care providers and insurers over what is actually covered, and the sense of guilt and frustration when you feel like giving up.

Big takeaway: People in the US spend a lot of time dealing with health burdens, increasing psychological costs and leading to foregone health care.

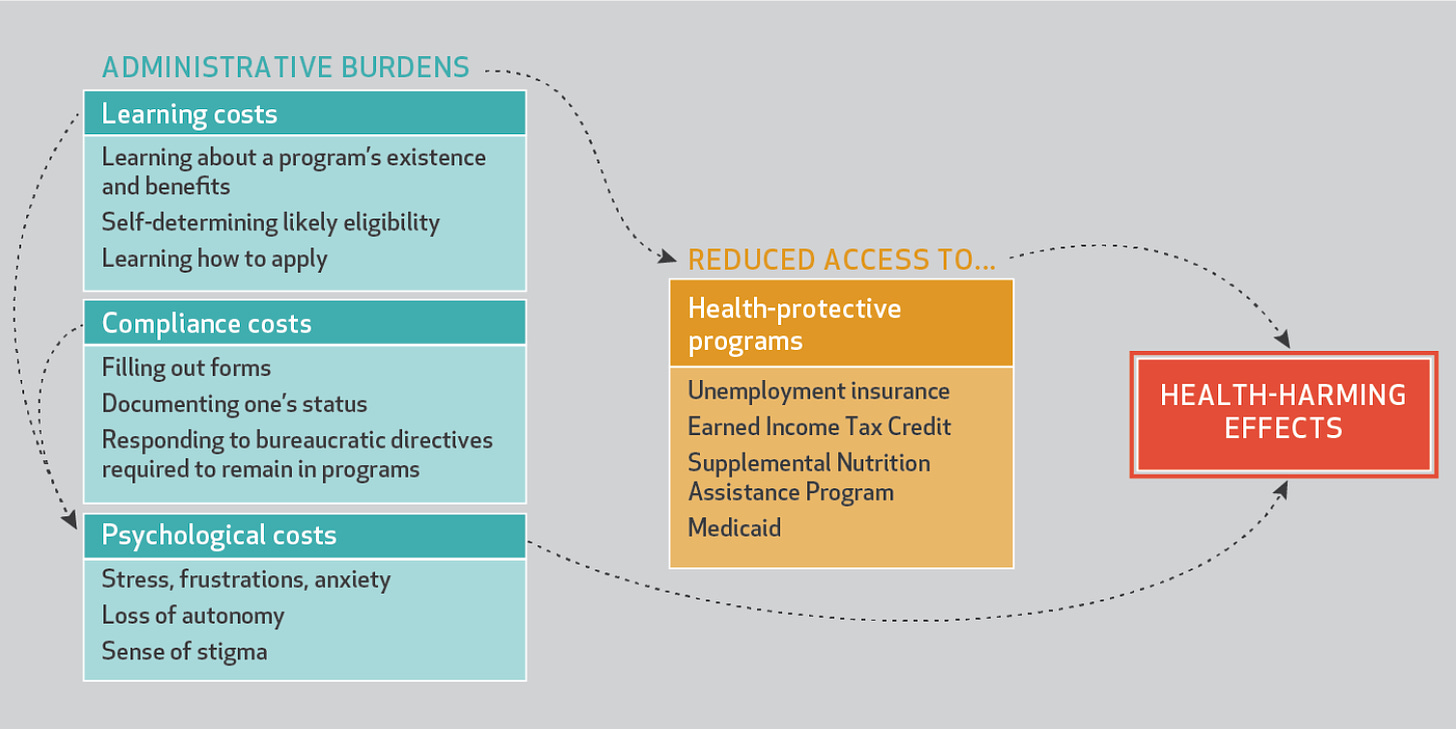

As Pamela Herd and I map out in Health Affairs, administrative burdens can substantially undermine health.

Source: Herd and Moynihan, 2020

A new wave of research has begun to make the nature of the administrative burden “time tax” tax more visible when it comes to health care. We already know the US health system is relatively inefficient. That’s part of why the US spends so much more while providing similar or even worse health outcomes than other countries. And health providers have long complained about burdens that are onerous for them. But to date there has been little attention to the costs on individuals.

Americans spend the equivalent of $22 billion worth of time dealing with health insurance administration

A recent analysis published in the Academy of Management Discoveries by Jeffery Pfeffer and co-authors estimated that direct cost of the time employees spent dealing with health insurance was $21.57 billion. Slightly more than half of that time was spent at their work place. In other words, we split the very large costs of being our own health administrators between us and our employers. This is one reason why private industry should be more concerned about the complexity of the US health system.

Burdens limit access to health insurance

We already know that burdens mean that people have less access to health insurance, and therefore health care. For example Medicaid is associated with better infant, child, and adult health outcomes, including for mental health. Administrative burdens make it harder for people to get Medicaid. An extreme example is the experiment in introducing work requirements in Arkansas, which caused more than 17,000 people to lose access. A study in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 95% of those losing access were eligible for the Medicaid even with the new requirements – they simply did not understand or could not manage the application process.

Burdens lead to forgone care

Even if you have managed the burdens of getting health insurance, there are a whole separate set of burdens when it comes to using it. Many people on Medicaid struggle to find doctors who will accept Medicaid payment. A survey undertaken by Michael Anne Kyle and Austin Frakt found that 73% of people reported performing at least one health care administrative task - scheduling, obtaining information, prior authorizations, resolving billing issues, and resolving premium problems - in the last year. One quarter reported delaying or forgoing needed care because of these administrative tasks.

Burdens limit access to health-protective programs

The ways that burdens worsen health are not limited to health insurance. We have increasing evidence that access to a strong social safety net is good for your health. Social supports such as SNAP, WIC, and the EITC lead to better health outcomes. For example, the loss of SNAP is associated with food insecurity and worse health for children. We also know that burdens like recertifying status and work requirements reduce access to SNAP. To the extent burdens make these programs less accessible, they worsen health.

Burdens create psychological costs, which worsen health

Beyond the tangible resources that burdens make harder to access, they also create psychological costs. One laboratory-based experiment showed that paperwork and confusing directions increased negative associated physiological responses, including electrodermal activity and heart rates. The experience of chronic stress worsens our health. Therefore, it seems reasonable to assume that the psychological costs created by burdens make us sicker, beyond their effects in limiting access to health benefits, like Mediciad, or health-supporting programs, like SNAP.

Natalie Shure wrote persuasively about the stresses that come from being your own health care administrator, which in turn make it harder for you to access affordable health services. A quote from a Mom with a son was in intensive care sums it up

“I think anyone who’s been through something like that understands that you’re not really high functioning in the aftermath of a tragedy. So to start getting the bills was just really bewildering….You have to sort through this mountain of paperwork and try to understand what you’re responsible for paying, what your insurance company is responsible for paying—and if there’s anything the insurance company doesn’t want to pay for, they just don’t.”

Dealing with such hassles becomes a source of frustration, stress, and even guilt for not doing enough.

The Pfeffer et al. study mentioned above offers one way of understanding the health effects of psychological costs, which is to look at the effects on employees. They found that those who spent more time dealing with health insurance administration (controlling for demographic factors and underlying health) were less satisfied and engaged at work, more stressed and burned-out, and more likely to miss work. The resulting absences were equivalent to $26 billion in costs, and productivity losses associated with lower satisfaction cost another $96 billion.

Health burdens worsen inequalities

One response to these findings is that maybe there is a silver lining. Maybe some frictions in health care are necessary – otherwise people would overconsume it. This is essentially the ordeals mechanism perspective most popular in the field of economics. The idea is that the people who don’t need the service will skip out on the hassles of getting it. As a result, policymakers can tell themselves that some burdens actually improve the targeting of limited resources to the truly needy.

The problem is that empirical evidence undermines that view. Frakt and Kyle found that burdens disproportionately reduced health access to those with high medical needs. Other work shows that those with more severe disabilities tend to be less likely to seek disability supports when Social Security offices close, making it harder to get help.

Instead of burdens improving targeting, they can operate as a Catch-22: those in ill health most in need of help struggle more to overcome the burdens needed to access that help.

Health care workers are gatekeepers of burdens, and subject to them

As noted with my co-author Pamela Herd, health care providers naturally think about burdens from their own perspective. Administrative hassles are a leading cause of physician burnout, leading doctors to spend twice as much time on paperwork as they do with patients. But those in the health care industry need to understand that burdens are not just something that they experience: they are also a huge challenge for patients.

Health care professionals can help by centering patient experiences into their understanding of burdens. This means understanding that health care providers are gatekeepers with the power to amplify or minimize burdens. For example, hospitals will sometimes help people sign up for Medicaid, rather than provide free health care. On the other hand, a new study found that 54% of doctors were unwilling to help patients get a health-based waiver for Medicaid work requirements even if the patient appeared to qualify for the waiver. Why? First, if doctors see completing the waivers as burdensome for them they are more reluctant to help their patients overcome their burdens. Second, conservative doctors were less likely to help, consistent with prior evidence that conservatives are more supportive of burdens in social programs.

If professional health workers struggle with health burdens, how are the rest of us supposed to manage them?

Given how big the consequences of health burdens are, it seems like we don’t talk about them very much. If dealing with them make you angry and stressed, you should at least know you are not alone. I’d love if readers shared their own health administration stories in the comments.

If you enjoyed this post, please check out the other posts and consider subscribing.

I have private insurance through my work. I worked very hard to get a physician to write a letter to my insurance company for me to receive a prior authorization to seek out-of-network care to get a second opinion, inclusive of further testing. Despite the prior authorization, my insurance denied payment for $12,000 of tests and visits that they authorized prior to my appointments. Phone calls to the insurance company resulted in a verbal commitment to fix the problem. Only a couple thousand dollars’ worth of claims were paid as a result of the phone calls. It’s taken me countless messages using the patient portal to spoon-feed both the insurance company and the out-of-network provider links between visit numbers, claim numbers, and prior authorization numbers to see that these claims got paid AND got applied to my existing bill as opposed to any future care. My bill is currently down to less than $100 but I’m still working to get it to $0.

My favorite example is that the insurance company has one code for a blood test yet the provider has one code to draw the blood and a second code to do the lab work. Because of this, only the cost of the lab work was covered

Short version - coding error at the radiologist caused me to be billed for my screening mammogram (a covered procedure under ACA). Insurance company was opaque, radiologist told me it was not coded as a screening procedure, that my PCP must have put the wrong words on the order for the mammogram. PCP's assistant spent her time proving this was not so, finally radiologist corrected their coding. Not even a "sorry about that from radiologist. Took 2mos elapsed time. This was an "easy" one. I've said in other cases, every seriously ill or elderly person needs someone to deal with their medical billing, it's ridiculous.