Don't look away: The post-Dobbs attack on women's health

The deprofessionalization of maternal health via a culture of uncertainty and fear

With the first anniversary of the Dobbs decision, it is clear it has radically narrowed access to abortion. More than 93,000 women were unable to get abortions in their home state in the first nine months after Dobbs. We can also measure the effect of Dobbs in terms legal changes, which are ongoing, and subject to court appeals. But I don’t think we fully understand the scale of the constraints in place, how illusory the promises of exceptions to abortion bans are, and the ways in which red state politicians are stifling democratic pushback. Dobbs has fostered restricted basic medical care in a way that affects any woman who becomes pregnant.

The anti-abortion movement has consistently co-opted women’s health as a justification for its actions. Protecting women’s health was the primary justification for TRAP laws that shut down abortion providers for failing to follow regulations not applied to any other out-patient services, often leaving women without nearby maternal health providers. More recently anti-abortion litigants have argued that abortion pills are unsafe, contrary to the evidence.

To be sure, maternal health is an area where there is a lot of room for improvement. The US has staggeringly bad maternal mortality rates compared to other countries. But the actual consistent effect of the anti-abortion policies is to worsen women’s health. The post-Dobbs era will compel dangerous full term pregnancies where the life or the health of the mother is threatened, or the fetus is not viable. It will create maternal health deserts in large swathes of the country as medical providers exit, unwilling to accept being blocked from using their medical training to help patients.

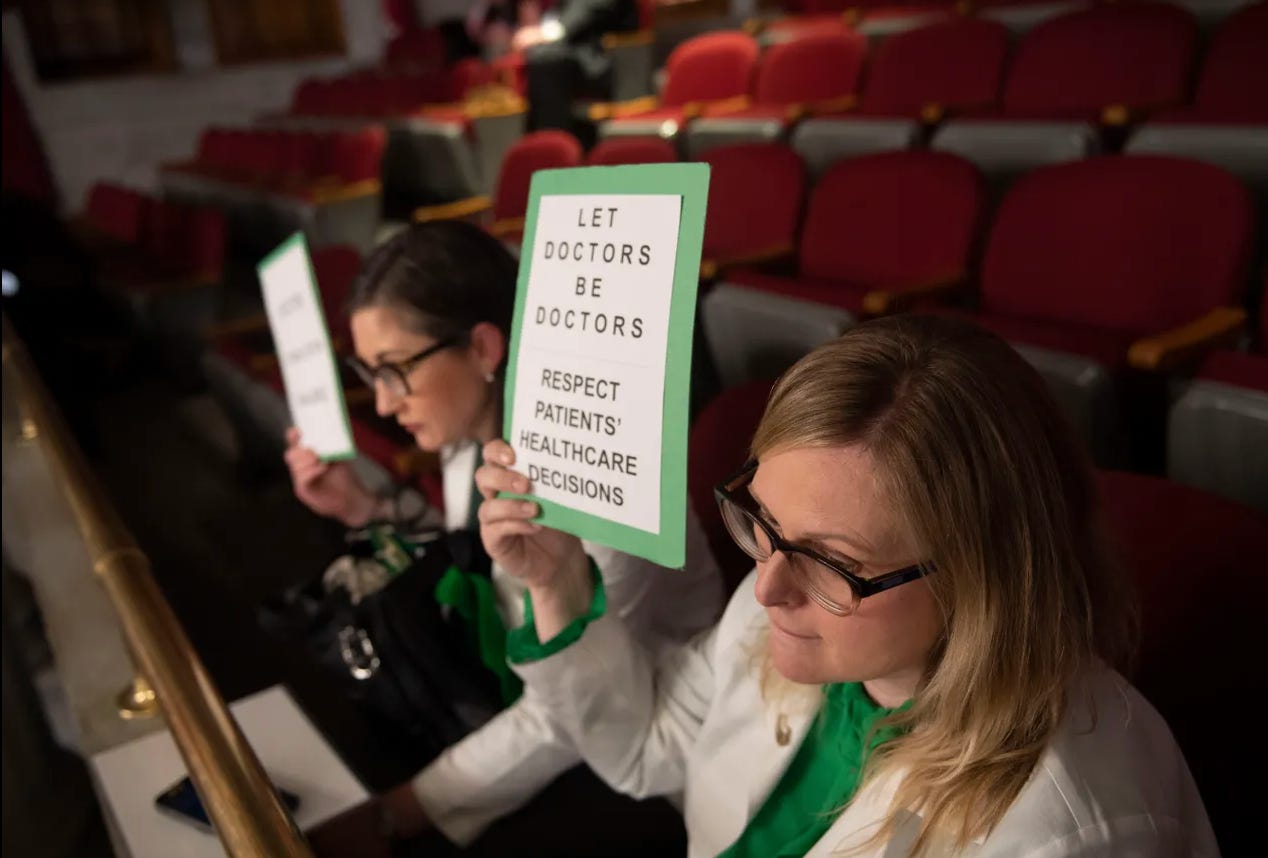

The mixture of post-Dobbs state laws and practices cumulatively represents a deprofessionalization of health care. By deprofessionalization, I mean a loss of the capacity of health providers to have autonomy over their actions, relying on professional medical norms and training. In more prosaic terms, this means the freedom of doctors and nurses to act according to the wishes and best interests of their patients.

We are seeing the state intervene in the doctor-patient relationship, restricting what doctors can say and do even when it clearly increases the health risks of patients. Such deprofessionalization is not unique to health providers in our current populist moment (see also education, or election administration). Fear and uncertainty serve as a central means to compel obedience to ambiguous laws.

There has been some extraordinary journalism done in this area, and this piece draws extensively draw from such work from Sophie Novack, Sara Hutchinson, Miki Meek, Amy Schoenfield Walker, Nadine El-Bawab, and Kavitha Surana. We are also relying on courageous women willing to reveal the intimate details of some of the most scarring experiences anyone might face.

Targeting health care providers

In the pre-Dobbs era, states limited access to abortion by targeting abortion providers. Abortion providers will continue to be intensely regulated in states where they are allowed to remain open. But the gaze of the state has expanded beyond providers like Planned Parenthood. OB-GYNs, medical staff needed for a surgery, and even pharmacists are now being forced to act against the interests of their patients.

For example, pressure from Republican Attorney Generals succeeded in stopping Walgreens, the nation’s second-largest pharmacy chain, from providing abortion pills, even though they remain legal. No new regulation was necessary, merely the threat that the business interests of a very large company could be jeopardized by political officials.

As women seeking abortions can no longer go to a Planned Parenthood or similar providers in much of the country, they turn instead of other physicians, especially OB-GYNs. In many of these cases, women with complex pregnancies are seeking advice. But in some states, physicians don’t feel safe mentioning the mere existence and availability of abortions. Take Texas as an example, one state where anyone who “aids or abets” an abortion is vulnerable to legal action, and providers risk a $100,000 fine and life in prison for providing an abortion.

“You can't do anything in Texas and I can't tell you anything further in Texas, but you need to get out of state” one woman was told. An OB-GYN noted “I have colleagues who say cryptic things like, 'The weather's really nice in New Mexico right now. You should go check it out.' Or, 'I've heard traveling to Colorado is really nice this time of year.’” Doctors are afraid to write down their advice to patients.

A culture of uncertainty and fear

Doctors working in maternal health in much of the country now face a culture of uncertainty and fear, where they do not know the limits of ambiguous and punitive laws.

A This American Life interview of an OB-GYN doctor in Idaho illustrates this new reality. She did not think of herself as an abortion provider, but one in five pregnancies before 20 weeks end in “spontaneous abortion” i.e., a miscarriage. Other pregnancies become complicated in other ways, as the fetus becomes non-viable or poses a risk to the health and life of the mother.

The new laws have torn down the illusion that it is possible to neatly separate abortion from basic medical care for pregnant women.

The OB-GYN must now worry about being sued for providing what she had done routinely in the past to protect her patients. New laws empower people other than the doctor and the patient, including any relatives of the woman or fetus. They can claim at a minimum, a $20,000 bounty, within four years of the health intervention. The doctor talked about the stress of dealing with a patient whose ectopic (non-viable) pregnancy had ruptured, putting her life in danger. Saving the patient is stressful enough, but:

Then, you add in this other weird layer of, is her brother going to not understand that this was a not-viable pregnancy and that her life was at risk? And what about her mom? What about her partner? What about her sister?

Do these people understand how serious this condition is, or do they only understand that I removed a pregnancy that had a heartbeat? I don't know. How am I supposed to know?

In Texas, and OB-GYN made a similar observation:

If a patient's grandmother and or partner or sister finds out that I've talked to them about an abortion, and that's something that really, really upsets them, all they have to do is find a lawyer and all of a sudden I'm 'aiding and abetting' someone into an abortion.

A Houston family medicine doctor who used to provide abortions put it this way:

We’re now bound and gagged from actually doing what we are trained to do. The ethics and the morality of that are just absurd. There are no ethics when we have to abide by a law that is in opposition to everything we know, all of our training, all of our understanding about actually taking care of patients and providing care.

And so the doctor now makes decisions that are not based on protecting the health of her patients. She takes the time to add language in files anticipating future lawsuits, she delays care, she sends patients to the ER. The concern is not irrational. She has kids. Idaho (like Tennessee and North Carolina) puts the burden of proof on the doctor in such cases — they have to prove the patient was in mortal danger. A conservative jury might disagree with her medical judgment. She might go to jail.

She is not alone. Doctors across the country are making the same calculation that women with risky pregnancies are too risky for them, refusing appropriate care, encouraging them to go to the emergency ward, another hospital that might take a different view of the law, or another state whose laws put higher value on the health of the mother. Some lawyers suggest that doctors will probably be protected, but one acknowledges: “When the penalty is 20 years to life, ‘probably’ is not good enough.”

Women are being denied basic health care

If doctors are fearful of providing basic standards of care, that means women are not getting that care, resulting in greater risk and worse health outcomes. It may be impossible to measure the scale of these unnecessary health events, since doctors and patients have an incentive not to draw attention to them. But each situation is grim. From a ProPublica piece:

Some of the women reported being forced to wait until they were septic or had filled diapers with blood before getting help for their imminent miscarriages. Others were made to continue high-risk pregnancies and give birth to babies that had virtually no chance of survival. Some pregnant patients rushed across state lines to get treated for a condition that was rapidly deteriorating.

A delivery nurse said that the new Texas laws meant:

no longer providing the standard of care that we would have prior to Dobbs. It meant patients sitting there for days, actively losing nonviable pregnancies, and us waiting for something to go bad enough that we could help them.

Dr Lorie Harper, chief of maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School, said:

Some doctors are no longer offering termination when there is risk of death for the pregnant patient. They are waiting until heart failure, waiting until hemorrhaging, waiting until a patient needs to be intubated, or is [having organ failure]. Patients have to be a lot sicker before they receive life-saving care – and not every patient who becomes that critically ill will recover.

Another Texas based doctor recounted a patient who

told us she wanted to decline the antibiotics so she could get sick enough so that we would offer her an abortion. And eventually she did get infected, and was delivered for that reason.

If they provide care, doctors also rely on less effective but more legally defensible modes of care. A piece on the effects of the Texas law noted in New England Journal of Medicine said:

The climate of fear created by SB8 has resulted in patients receiving medically inappropriate care. Some physicians with training in dilation and evacuation (D&E), the standard procedure for abortion after 15 weeks of gestation, have been unable to offer this method even for abortions allowed by SB8 because nurses and anesthesiologists, concerned about being seen as “aiding and abetting,” have declined to participate. Some physicians described relying on induction methods to get patients care more quickly; others reported that their colleagues have resorted to using hysterotomy, a surgical incision into the uterus, because it might not be construed as an abortion.

A New Mexico OB-GYN, Dr. Eve Epsey recounted what happened to a patient from Texas whose fetus had a fatal condition, where the mother ended up hemorrhaging and needing a hysterectomy:

That was a doctor who didn't tell her, 'Go get care out-of-state.' She was an immigrant. It took her six weeks to figure out she could travel to New Mexico for an abortion and get the logistics and finances together to be able to go. This is a patient who — if she had been able to have that pregnancy termination at 11 or 12 weeks — very likely would not have lost her uterus the way she did when she was 16 to 17 weeks.

Mayron Hollis, in Tennessee was denied preventive care to end a pregnancy, even though she had cesarean scar pregnancy, with the pregnancy bulging out of her uterus, creating real risks to her life. She wanted the baby, and it took time for her and her husband to understand the scale of the risk, and then decide to abort, in the interests of her health and so that her children would not risk losing their mother. By the time she did so, in her 11th week of gestation, Tennessee’s trigger ban was in effect. In theory, doctors could perform the abortion, and defend themselves in a court case by pointing to the risks of serious and permanent bodily injury to the mother, but she could not assemble the team of specialists necessary to take the risk. As the pregnancy progressed, it became more complicated and dangerous. The placenta attached to her organs. She began bleeding heavily, requiring hospital stays. The only way to stop the bleeding, physicians told her, was a hysterectomy she did not want.

Even for women who emerge with no lasting physical damage, there are the psychological costs of being forced to carry a fetus that you know will die, that family, friends and strangers will ask you about as you are denied the privacy of your grief. Or a fetus that might kill you, but where the evidence is not strong enough for the doctors to act. Instead of planning for a birth, you spend your time planning for a death, possibly your own. ProPublica tracked a risky pregnancy of another woman in Tennessee.

As friends and coworkers began to ask her about her visible pregnancy, Hollis acted excited. But there was nothing happy about the experience. She constantly worried about what her husband and [child] Zooey would do if she died, and called up the Social Security Administration and her union to find out what kind of survivor benefits existed. She moved through her days trying to pretend she wasn’t pregnant. It was the only way to keep the overwhelming fear at bay and continue working. Then, in mid-November, her employer laid her off, saying it couldn’t accommodate the work restrictions required by her doctor.

Health care access will further decline as providers exit deprofessionalized spaces

Medical professionals get into medicine to help people. As they fail to do so, they might decide to exit the profession, or at least the state which is stopping them from providing the best care to their patients. Miki Meek talked to OB-GYNs in Tennessee and Texas, who ultimately decided they could not stay in a state where the logics of medicine — protect your patient, minimize risk — could not longer be practiced:

And each of them described the same kind of moment to me. One day, they found themselves in a terrible situation with a patient, brought on by trying to comply with the new laws. One of them had to send a patient to another state in an ambulance. It was a five-hour ride. The patient's blood pressure was rising, and by the time she got to a hospital, her kidneys were starting to fail.

The other doctor had to turn away a patient pregnant with twins. One of the twins was going to die and the doctor needed to intervene to save the other's life, but he couldn't because of the laws. He doesn't know what happened to the patient, but he knew, I need to leave.

One doctor based in Texas discussed leaving because

I’m not allowed to be a doctor…If every OB—let’s say every OB you talk to who felt similarly—decides to leave the state, we just have fewer OBs here, even less access for these patients. And that doesn’t feel like a viable solution.

A Texas nurse who had seen patients being left to suffer soon left her job soon after “a couple of cases just within a few weeks of each other that I really, really, really struggled with.”

Doctors, even those not working in areas related to abortion, are more reluctant to work in red states after Dobbs. Texas already has a significant shortage of qualified physicians, especially for OB-GYNs, and especially in rural areas. Half of Texas counties lack any women’s health provider.

Health care professionals are torn between providing services to populations who need them, and state governments who make them worry about providing basic standards of care.

To be left with the option of either potentially breaking the law and putting myself, my family, at risk, or not offering the options to a patient and not meeting her needs and providing care—I think it’s a tragic, horrible situation to be in. And then if you leave, you know, there’s so many women that need care in this area. Do we just abandon the women of South Texas?

Exceptions to abortion bans are a false promise, a fig leaf against unpopular actions

What about exceptions? After all, many of the states discussed have some sort of exceptions for medical emergencies, threats to the life or health of the mother, or other cases, such as rape and incest.

The exceptions exist on paper, but not in practice. In states with exceptions, abortions have declined to almost zero, even as experts say the number of people who qualify for such exceptions are in the thousands.

Why are exceptions to hard to access? One reason is that states that have so significantly restricted abortions are likely have few abortion providers as a result. Another reason is that the majority of women do not file reports to police when they were sexually assaulted and abused, but such reports are typically required to claim the exception of rape or incest. In some states, doctors have to verify that the reporting took place.

But it is also clear that physicians don’t believe the exceptions are real. Birth defects kill thousands and most families with a fetus with a birth defect seek an abortion. But increasingly doctors do not know if they can treat them with an abortion. So, even though Indiana offers an exception, lawyers from an Indiana hospital do not believe they are allowed to do so because of confusing wording. Utah requires that the abnormality is “universally lethal” which is an unlikely standard to gain consensus over.

A similar dynamic occurs for women who face significant health risks. The same culture of uncertainty and fear is closing off choices.

Dr. Ragsdale thought the Ohio woman was a clearcut case for the state’s health exception, but her hospital’s lawyers thought the threats to the patient’s health were not immediate enough. (The ban has since been blocked in court.)

Dr. Ragsdale’s patient traveled to Michigan for the multifetal reduction. In Indiana, Dr. Day also thought it would be simpler to refer her patient to Michigan or Illinois, rather than try to track down a willing doctor in the state.

Dr. Day said the patient told her she could not afford the travel or medical fees not covered by insurance. She did not hear from the patient again.

“What gets put out to the press is: ‘We have exceptions for fetal abnormalities and we have exceptions for maternal life,’ ” Dr. Day said. “When you get into the nitty-gritty details of it, you actually don’t.”

Health providers ultimately tell patients that it is easier to travel out of state than to negotiate the thicket of exceptions. (Or, if they are in Texas, they might not even tell them that).

If exceptions don’t allow doctors to help patients in difficult and unusual situations, what is their purpose? They allow policymakers to claim that their anti-abortion policies are restricting unnecessary abortions, but providing room for necessary ones. This is another false claim, another lie upon which women are losing their access to basic health care.

Oklahoma provides an example. It has a series of overlapping and confusing abortion laws and exception, with the predictable effect of limiting access to care. Jaci Statton, a mom of three in Oklahoma, had a molar pregnancy, where there is no chance the fetus can survive. But medical professionals judged she was not yet sick enough to be treated. According to Statton:

They said, 'The best we can tell you to do is sit in the parking lot, and if anything else happens, we will be ready to help you. But we cannot touch you unless you are crashing in front of us or your blood pressure goes so high that you are fixing to have a heart attack.'

Policymakers in red states are limiting popular pushback

If the current laws are not working, what about changing the laws? After all, trigger laws written after Roe but before Dobbs were written before the reality of the consequences of their effects could be observed. Older laws (like Wisconsin’s 1849 law) reflect an era where the type of medical options available to women were vastly different.

When the Dobbs decision was handed down, anti-abortion foes, including those on the Supreme Court, presented it as a victory for democracy. Judge Alito declared that the effect of Dobbs was to “return authority to the people and their elected representatives.”

But that has not proven to be the case. As political scientists Jake Grumbach and Christopher Warhshaw point out, large majorities of the public support abortion in most states. And voters are aware that abortions have become more inaccessible in states with abortion restrictions. Thus, there is a basis for democratic pushback.

But the laws that have been triggered or passed have gone in the other direction. Thus far, sponsors of the anti-abortion laws have shown little interest in responding to the problems I’ve identified, suggesting that they view a culture of uncertainty and fear as helpful to their cause. One exception has been Tennessee, which has explicitly provided an exceptions for ectopic and molar pregnancies. But more often, state legislatures in red states are doing all they can to prevent public opposition to abortion bans from being converted into votes and policies. After voters in Kansas and Kentucky voted against more severe abortion restrictions, the lesson for elected representatives was that they, and not health professionals, or the public at large, should make decisions. Thus, even in states with referenda, legislatures are proposing to make them more difficult to organize.

The drip, drip, drip of excruciating cases

It is worth asking what it will take to shift the equilibrium. Normal policy feedback processes have been undermined. A new equilibrium may be achieved as we see the consequences of the post-Dobbs world. Maybe things will change when the first doctors are arrested, or a patient dies. But we are already seeing a drip, drip, drip of excruciating cases. Will it be enough to shock people into action? Or will we collectively become inured to it, and turn away?

I honestly don’t know the answer. The epidemic of school shootings shows the limits of harrowing stories to change minds, and policy. The polarization of the media also shapes how those stories are told, or if they are told at all. For example, the story of 10-year old child traveling to Indiana to receive an abortion she could not access in Ohio was first dismissed as a hoax in right-wing media, then as a failure to understand the laws in Ohio, and then as a story of how the medical provider in Indiana behaved illegally.

The OB-GYN, Caitlin Barnard, had in fact followed the law by reporting the case before new trigger deadlines were in place. It did not matter though. A vindictive Indiana Attorney General, Todd Rotika, pursued her with the goal of exacting revenge, even using consumer complaints from people who were not her patients.

Ultimately, a medical board of political appointees punished her with a fine by claiming that she violated patient privacy rights by providing de-identified information to a reporter about the case. This is ridiculous, of course. The politicians pretend to care about the privacy rights of a 10 year old as they cheer the removal of privacy rights of the control of her own body. They punish the one doctor that was willing to help her while they sought to deny that help. Barnard’s real crime was pulling back the curtain to reveal reality of what the post-Roe world would look like in all of its grotesque hypocrisy.

Meanwhile, policymakers are working to block popular means of changing unpopular policies, reflecting the point that the reversal of rights in one domain is often built on limiting democratic rights. Unless those policymakers decide it is in their interests to change, or they themselves are replaced, their policies will continue to put women’s health in danger.

Thanks you. Collection of the relevant facts. Recommend also Jessica Valenti's Abortion Evey Day for the full, gory, story of this performative, vicious cruelty.