GOP populism is hurting the teaching profession

The real consequences of a manufactured crisis

We are living in a populist era that frames public officials as corrupt elites. The effects of the ensuing hostility to the capacity of public institutions to function feels like a big missed story of our time, one whose consequences will be felt for years if not decades.

This story is playing out in multiple policy areas, but educators are at the front lines. Teachers in America, like most parts of the world, have had a brutal couple of years. They have had to work through a pandemic, and were criticized for not being quick enough to get kids back into classrooms.

But American teachers faced an additional strain, which was the flare-up of anti-institutional populism. The wearing of masks became a flashpoint, resulting in protests and anti-mask mandates. Teachers have been accused of brainwashing kids with a CRT ideology most of them would have been hard pressed to describe a few years back. They are facing book bans, new constraints on how they discuss race and gender, and demands for transparency in the most minute detailing of lesson plans. And they have been grotesquely tagged as “groomers” if they discuss gender identity. Evidence-based pedagogies like “socio-emotional learning” have suddenly become questionable, presented, falsely, by Republican leaders, as a form of CRT “by another name.”

Such changes are going to make the teaching profession less attractive, and our schools less able to attract and retain good teachers. We just don’t know the scale of the damage yet.

Fenno’s paradox for schools

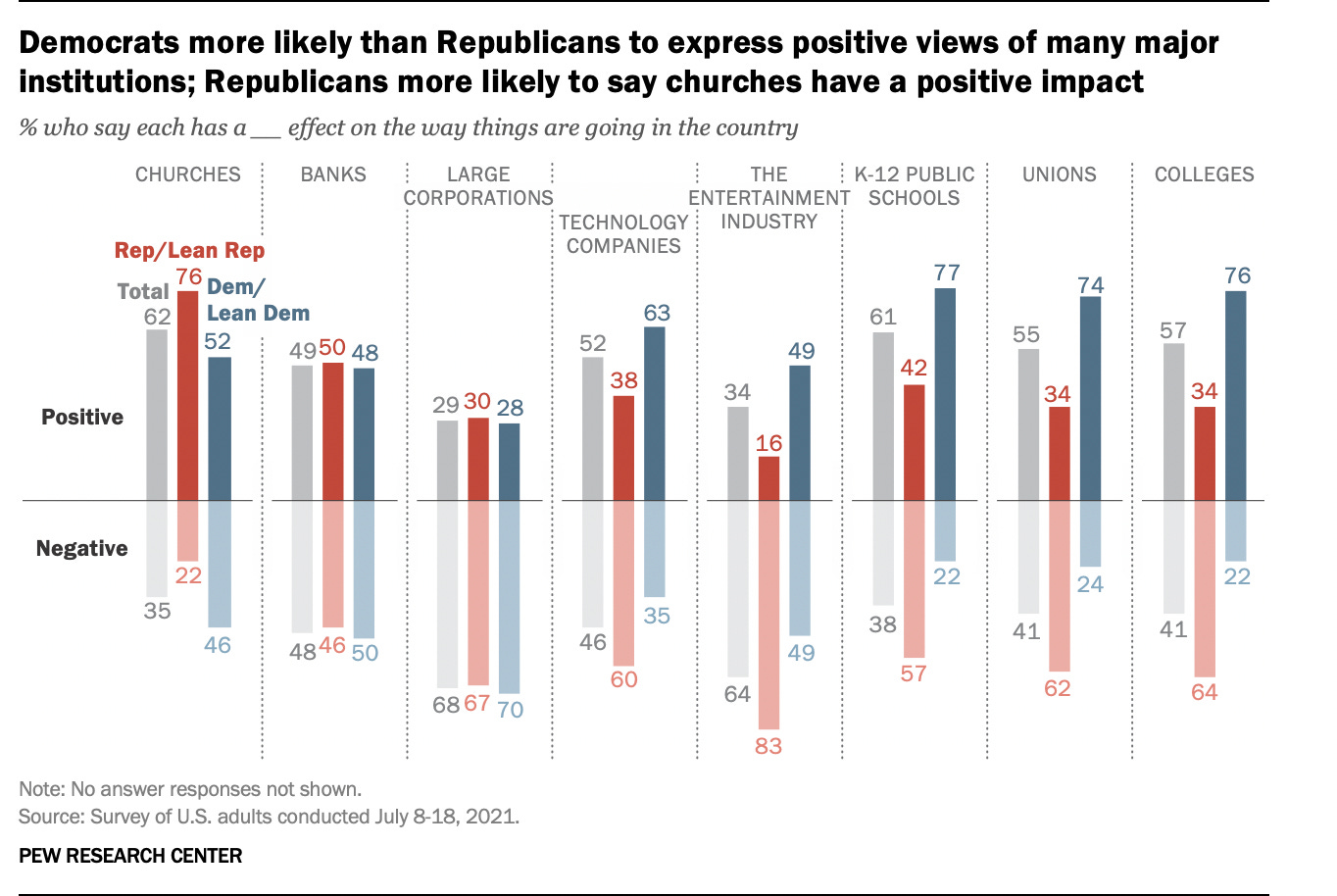

There are plenty of polarized and negative views about public schools. This partly reflects a reshaping of the conservative movement to one that is distinctly anti-institutional. Churches are the only of the listed institutions below that enjoy majority support from conservatives. This shift is especially obvious in the domains of education, where 57% of Republicans and two-thirds of conservative Republicans say public schools have a negative effect on America.

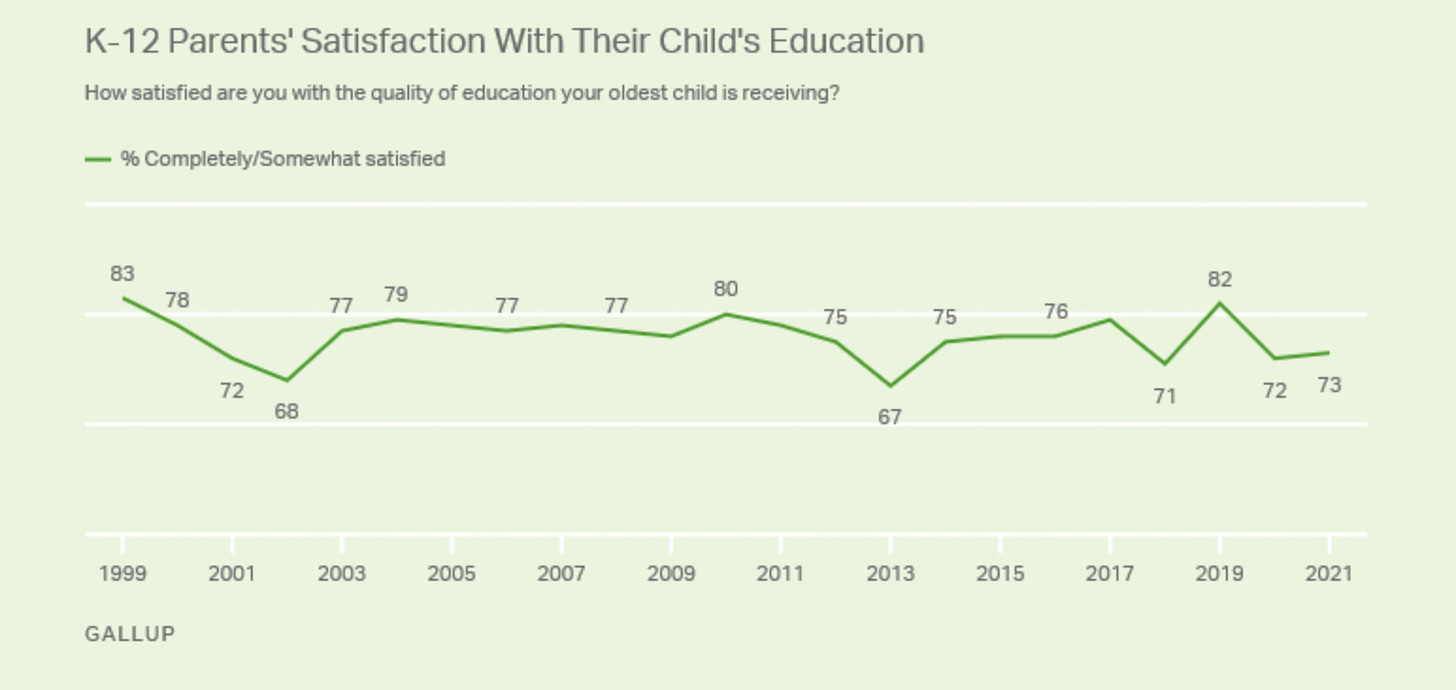

The weird thing about it is that most parents are happy with their kid’s school, even Republican parents. There is certainly a drop in parental satisfaction that accompanies the pandemic, but not to historically low levels.

Another poll confirms this general satisfaction:

88% of parents agree "my child's teacher(s) have done the best they could, given the circumstances around the pandemic."

82% agree "my child's school has handled the pandemic well."

76% of respondents agree that "my child's school does a good job keeping me informed about the curriculum, including potentially controversial topics."

Less than 20% believe that schools teach about sexuality, history, or race, in ways that contradict their family values.

We could think of this as Fenno’s paradox for public services. Fenno’s paradox is named for the great political scientist Richard Fenno, who observed that while people distrusted Congress as an institution, they generally liked their own member of Congress. The same distinction exists between specific public services and government as a whole. For example, a recent poll found that even the least popular federal agency, the IRS, was more popular than “government.” When we are asked about specific public services, especially those we have experience with, this strips away much of the ideological baggage that comes with our views about broader institutions. With actual experience of public schools, most parents are better placed to evaluate what teachers are actually doing, and the challenges they need to juggle. As a result they are more favorable than the general public is about schools in general.

Teachers do not feel respected

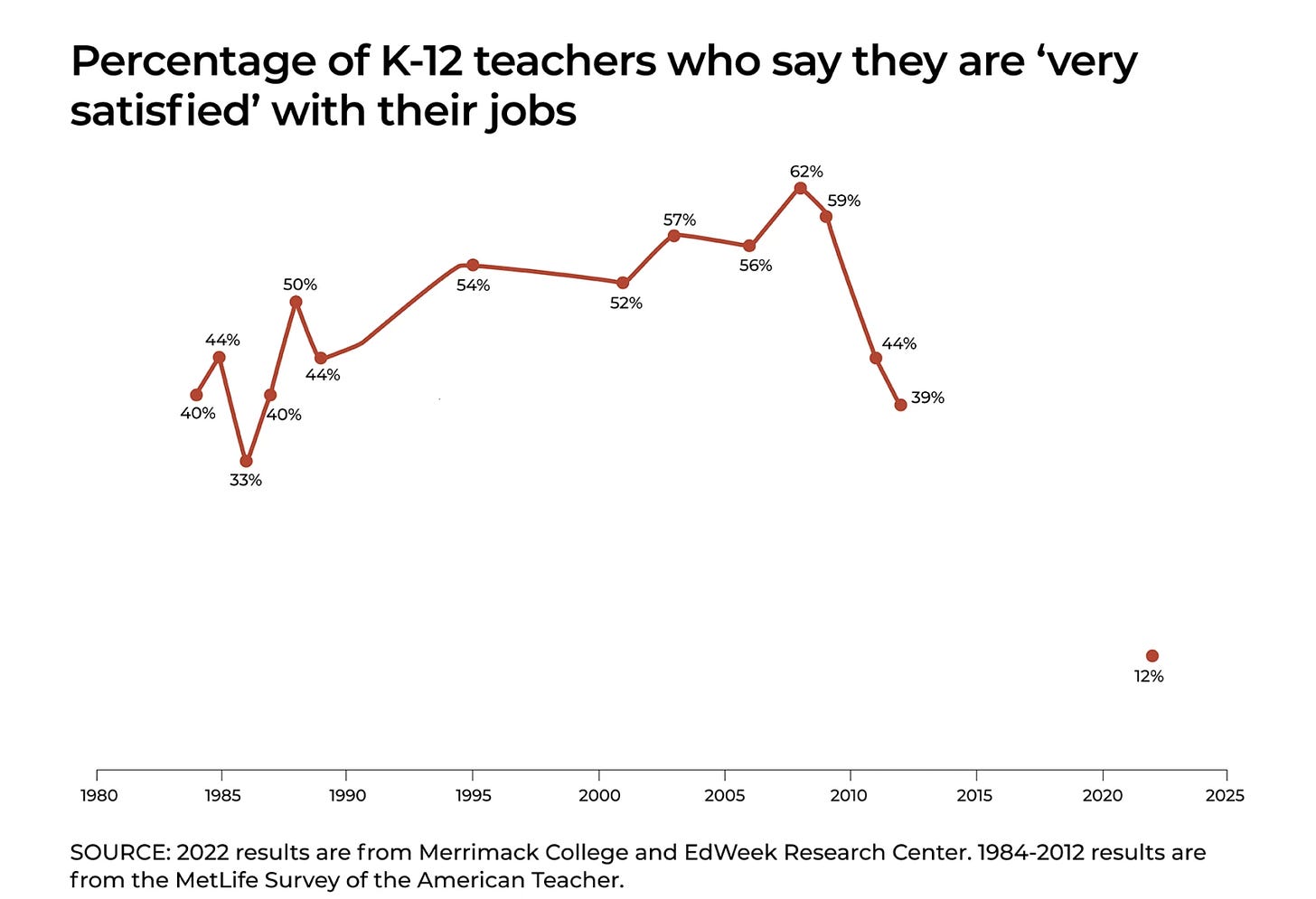

If the majority of parents support teachers, it may feel like a silent majority to teachers. There has been a collapse in teacher satisfaction.

Teachers have also become less likely to believe that the public respects them. In 2011, 77% of teachers felt respected by the public. That number is down to 46% today, though 76% among parents, suggesting that teachers do indeed understand that they are viewed differently by the general public and the families they serve.

What are the implications of Fenno’s paradox for the evolution of educational politics? As schools are increasingly framed in culture war terms, policy decisions about the educational profession are shaped by a polities with a less direct and more negative understanding of what teachers do. Put another way, teachers are becoming more beholden to the modal Fox News viewer than the families they serve. Exaggerated or false stories about teachers brainwashing students have become the primary way that many view schools.

You can't engage in a non-stop attack on a profession without making the profession less attractive

We don’t have a full picture of the scale of the current wave teacher shortages, but it looks bad. While it would be too simplistic to suggest that teacher shortages are purely the function of culture war politics, I do want to suggest that a multi-year, multi-pronged campaign of attacks on the teaching profession will have some negative consequences.

About 35% of school districts reported in 2021 that they had been adversely affected because of anti-CRT efforts, and the number is surely higher now. In some states, teachers have lost protections due to new laws that put their jobs at risk if they stray on the wrong-side of the culture wars. Teachers are also vulnerable to legal liability. For example, the Arizona legislature passed a law that would allow parents to sue teachers if they “usurp” parent’s “fundamental right to direct the upbringing, education, health care and mental health of their children.”

Many of these laws are ambiguous, leaving teachers in a state of extraordinary legal uncertainty about how to do their jobs. In states where schools have become a popular punching bag, politicians will use state power to further undermine them.

For example, the Governor of Oklahoma is auditing Tulsa public schools on the grounds that they are suspected of teaching Critical Race Theory1: what this means is unclear, but if you were a teacher in Tulsa how comfortable would you be, for example, teaching about local history like the Tulsa race massacre of 1921? While the state Education Department provided guidance about how to teach the event in 2019, this seems difficult to reconcile with the state’s more recent anti-CRT law, especially if students are curious enough to ask questions about underlying causes and long-term consequences of such events.

Teachers, and education officials more broadly, have experienced harassment and been forced out of jobs. Teachers also have reason to worry about personal safety. Let’s set aside the 27 school shootings that have already occurred this year. One school in Wisconsin faced bomb threats and threats against school officials after a Title IX investigation about pronoun use occurred. The person making these threats was not a parent or even a Wisconsin resident, but a California resident who had read a culture war take on what was happening.

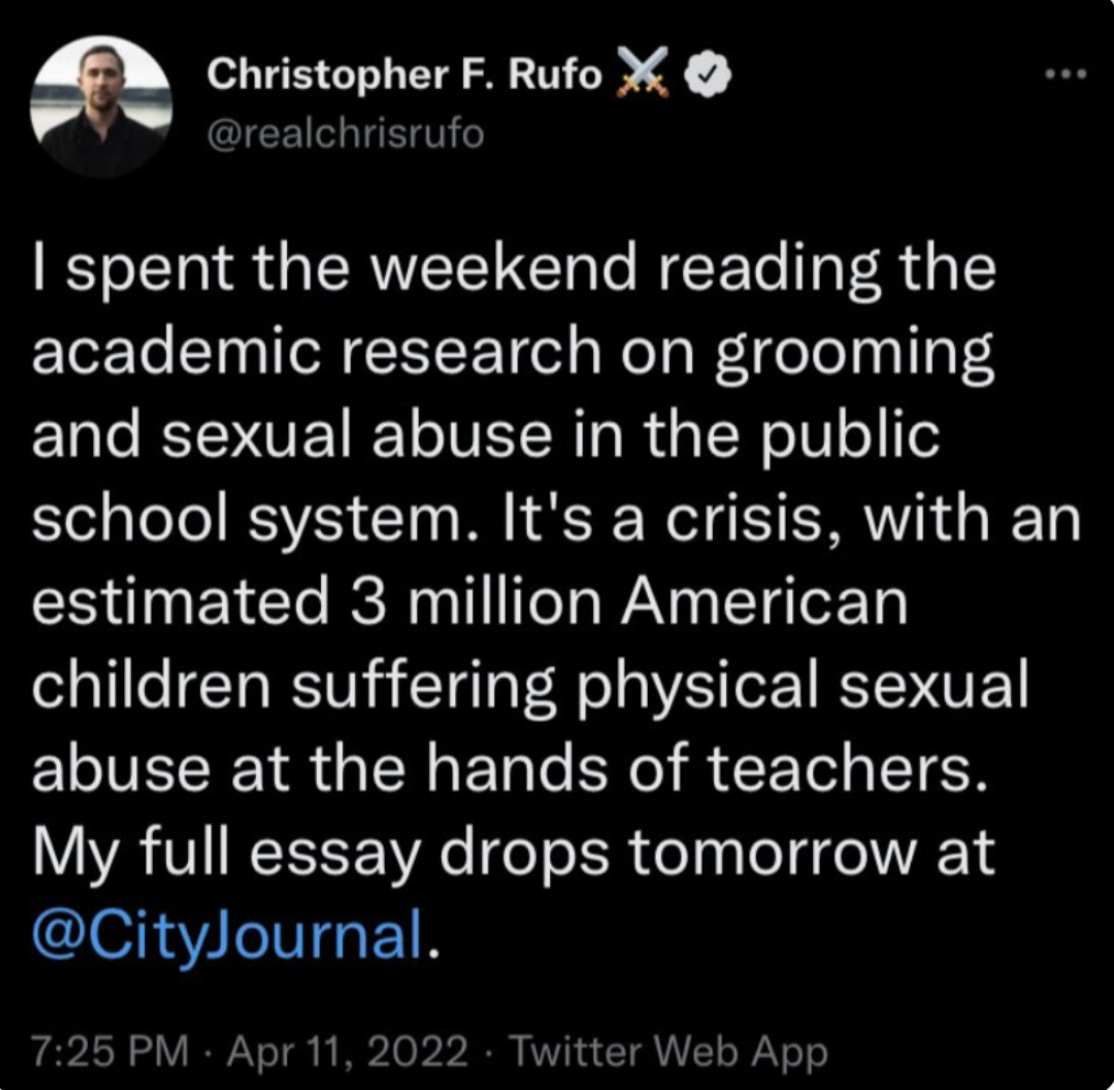

As the campaign to label educators as “groomers” has taken off (thanks Manhattan Institute!)…

…there has been more reason for educators to worry about their personal safety.

What do teachers think?

In a narrative that is largely driven by pundits and advocates, it is clarifying to hear from the teachers being put in the crosshairs of the culture wars. Some of my students at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University interviewed public school teachers from all over the country about the changes they have seen in their jobs. The overriding sense is that they feel less empowered and under greater negative scrutiny for reasons that are unrelated to student performance.

Some talked about new “transparency” requirements that demanded they provide teaching materials at least three weeks in advance, making it impossible to use discussions in the news:

I've tried to be very proactive about sending stuff in. But if I find a video about a current event in the morning before class, I can't use it. It’s one more thing to slow us down.

Some discussed the difficulty they have in addressing legitimate student concerns or accurately covering history and race:

*There are questions that arise in the classroom that you can't answer, you have to give ambiguous answers, and that's the part that really hurts kids. It's crippling, it's awful.

*It's hard to talk about the Chicano Farmworkers’ Association and where it originated without talking about inequities…I'm not going to even touch that right now because all it takes is one parent to complain and there you go…I find myself tiptoeing around language.

*I would do a huge unit on Black History Month and Women's History Month, but I can't do it at this school because I don't want the pushback. So I'm just reading from a textbook.

*Parents have been outspoken about me speaking about racism in the classroom. I had a parent complain during conferences and said that racism doesn't exist anymore…In our curriculum, there was this reading written from MLK's sister's perspective. And the parent was saying I don't know why this is being discussed anymore, this was so long ago. The textbook had a question about why someone is being racist, and the parent crossed it out and wrote ‘was’ to show that racism isn't happening anymore.

At a time when “self-censorship” is treated as a major concern on college campuses, we have seen less discussion of how terrified teachers feel afraid to say the wrong thing, when the “wrong thing” might be an accurate account of history, power or race in America.

*But there's been this trickle of fear…there are new laws where if a student is uncomfortable with what's being discussed in the classroom, a teacher could get fired. So there's just this fear.

*I do think twice before I answer questions because I know that at this point anything goes, and certain powers out there want a martyr or to make an example out of someone, which is sad. I would be out of touch with reality not to think about that.

And some considered the long-term effects on their profession:

*There’s a lack of trust in educators and it doesn’t make sense because educators are professionals who are extremely well trained and I have never met an educator who went into the profession to harm a child.

*What’s education going to look like ten to twenty years from now? Fewer quality teachers, fewer lively discussions than we need. If we’re not preparing kids to have difficult conversations, what are we doing?

Who would want to be a teacher under such circumstances?

Teaching is already not the most attractive profession. It is not terribly lucrative. Fewer people are taking education as an undergraduate course of education - it was about the 200,000 per year in the 1970s, and it’s about 90,000 now, in part because women have a broader array of economic opportunities.

As populists make the profession impossible, removing autonomy to do the job, creating a culture of fear, intimidation and censorship, more and more talented teachers will head to the door, or never join the profession in the first place.

Such unanticipated consequences may not be wholly unanticipated or even undesired. Advocates like Chris Rufo see their public schools as inherently corrupt: “Public schools are waging war against American children and American families,” so families should have “a fundamental right to exit.” Such a radical view justifies a campaign either asserting ideological control of schools (as we are seeing in red states) or a deconstruction of the public school system by making them so toxic that politicians direct more public money to private schools instead.

One big problem with this scorched earth approach is that the vast majority of students are in public schools. Making schools an ongoing culture war battleground will generate massive and ongoing damage to a core American public institution, leaving teachers with less ability to focus on their job of educating well-rounded students. Republicans might win this battle — in many places they already have — but it comes at a real cost to the educational experiences of our children.

I would love to hear from educators in the comments about their experiences. If you found this post useful, please check out the archive, consider subscribing if you have not done so, and share with others!

Governor Stitt also says there are financial irregularities to be audited, but given how scandal-plagued his administration has been (including handing out $18M in federal education funds with no oversight), and the amount referred to was $20,000 two years ago, which was already reported by the district Superintendent, it is hard to give this explanation much credence.

I am a Professor at a major State University and my wife is a high school teacher.

This essay is wildly inaccurate about what is happening in education, and Rufo is totally correct.