The battle over abortion pills is also an attack on state capacity

Welcome to a public health regulatory regime where administrative expertise plays second fiddle to the preferences of conservative activists

You have a medical concern. The pharmacy sells a drug that claims to resolve it. But is it safe? You have two ways to answer this question:

Option A): Based on data analysis and testing, a group of non-partisan scientists will evaluate the efficacy and safety of the drug. They are accountable to elected officials, the media and courts for their failures.

Option B): A Judge, who opposes the resolution of your health concern, appointed by someone who pushed anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, selectively draws evidence from like-minded activists to make decisions. He has a lifetime appointment.

The answer should be clear enough. And yet, with a single opinion, a judge in Texas has made the choice for you, selecting option B.

Because Judge Matthew Kascmaryk’s breathtakingly broad decision to ban the abortion drug mifepristone is not just a nationwide ban on the most widely used abortion drug across the country. It sets a precedent that undermines the ability of citizens to rely on the state to ensure a safe and evidence-based process to approving medical products. The 5th Circuit order largely reaffirms this deeply troubling precedent.

The focus, understandably enough, on Kascmaryk’s decision has been on the immediate effects in extending the Dobbs-era prohibitions on abortion. But the implications are even broader.

I want to make four big points about how the courts have treated mifepristone:

It reflects a broader judicial philosophy of undermining state capacity.

Anti-abortion judges are willing to go especially far in this domain because of their personal convictions, reflected in a remarkable degree of judicial pretzeling.

The resulting decisions create a nightmare regulatory regime beyond the domain of abortion, most obviously for the pharmaceutical industry and government regulators.

It is built on hypocrisy: specifically the claim that the judges are acting to protect women’s health, when their real interest is in curbing abortion.

The anti-expertise judicial tide drowning state capacity

I am interested in administrative capacity, but not an expert on drug regulation. So I contacted Patricia Zettler, an Associate Professor of Law at the Ohio State University. She is an expert on health law and regulation, and also served in the FDA’s Office of Chief Counsel. How unusual is the Kascmaryk decision?

The Texas ruling is, without question, a change from business as usual. I am unaware of any previous case in which a court has removed a drug from the market over FDA’s objection. And the very strong reaction from biopharma companies (letter available here) is evidence of just how big of a deal this is. Everyone should understand that the stakes of the Texas ruling are not about one drug, but about pharmaceutical innovation and patient access more broadly.

Historically, courts have recognized and deferred to agency expertise on issues where the law was unclear, and especially where judgments were based on technical knowledge. This system that has worked fairly well. The logic of such deference was relatively uncontroversial a generation ago, when John Paul Stevens wrote in an unanimous ruling establishing Chevron deference that “Judges are not experts in the field and are not part of either political branch of the government.” Increasingly that is no longer true, and as I noted last year, Trump appointees, especially Supreme Court nominees were selected partly based on their hostility of the idea that they should defer to expertise.

I also asked Dan Carpenter of the Kennedy School at Harvard about the what is happening. Carpenter has spent a great part of his career writing carefully about the relationship between agency reputation and autonomy, specializing in the FDA. He has argued that the reputational incentives for the FDA are to avoid error, and thus to delay or not approve drugs that might be contentious — not to rush unsafe drugs to market, as they are being accused of doing in this case.

The FDA has accumulated a fair degree of autonomy and trust partly because of the scientific nature of it’s tasks, but also because it has managed to avoid making large errors. The new willingness to second guess that expertise occurs in the absence of evidence of failure. Mifeprostone is not a drug that has suddenly been discovered to be unsafe (more on that below) — rather, we have a new model of judicial politics willing to advance the claim that a drug is unsafe without evidence. If that means trampling on the expertise and autonomy of regulatory experts, so be it.

Here is what Carpenter said:

I think this decision does reflect a certain view among the right of agencies as political tools to accomplish ideological ends. If we’re certain about right and wrong and there is little role for evidence to persuade us, then let’s face it, that’s all that agencies are, and not just in the abortion domain. It’s all the more pervasive in abortion politics because there are strong beliefs across the spectrum that dispense with or ignore non-confirming evidence.

Judge Kacsmaryk is swimming with an anti-expertise tide, testing how far it may go. His views may reflect an extreme upending of how the administrative state operates, but it would be a mistake to conclude they are unusual. Twenty-two Republican Attorney Generals filed an amicus briefs supporting the ban, the same Attorney Generals who successfully pressured Walgreens, the nation’s second-largest pharmacy chain, to stop providing abortion pills, even though they remain legal.

Anti-abortion beliefs and judicial pretzeling

In a piece in the New England Journal of Medicine, Profesor Zettler and co-authors pointed out that when abortion is concerned, the normal rules don’t apply:

There is a well-recognized pattern of “abortion exceptionalism” in the United States, wherein legal rules and principles of legal interpretation aren’t followed in the context of abortion.

This is evident in the highly motivated judicial pretzeling that Kascmaryk performed to even hear the case. He ignored a six year statute of limitations, and launched an extraordinary broad definition of standing. As Mark Joseph Stern notes: “Kascmaryk said physicians who may treat patients who have side effects from medical abortions prescribed by someone else are sufficiently injured by mifepristone to sue.” If the Dobbs decision demonstrated a new conservative aggression in using the law to achieve a pre-determined purpose, Kascmaryk took it to a new level.

The 5th Circuit unwound some of Kascmaryk’s pretzeling but left a disturbing amount in place. This is not a final decision, but provides a sense of how far a relatively conservative court will go on abortion. It lays out a trail of breadcrumbs that the conservative SCOTUS majority might pick up.

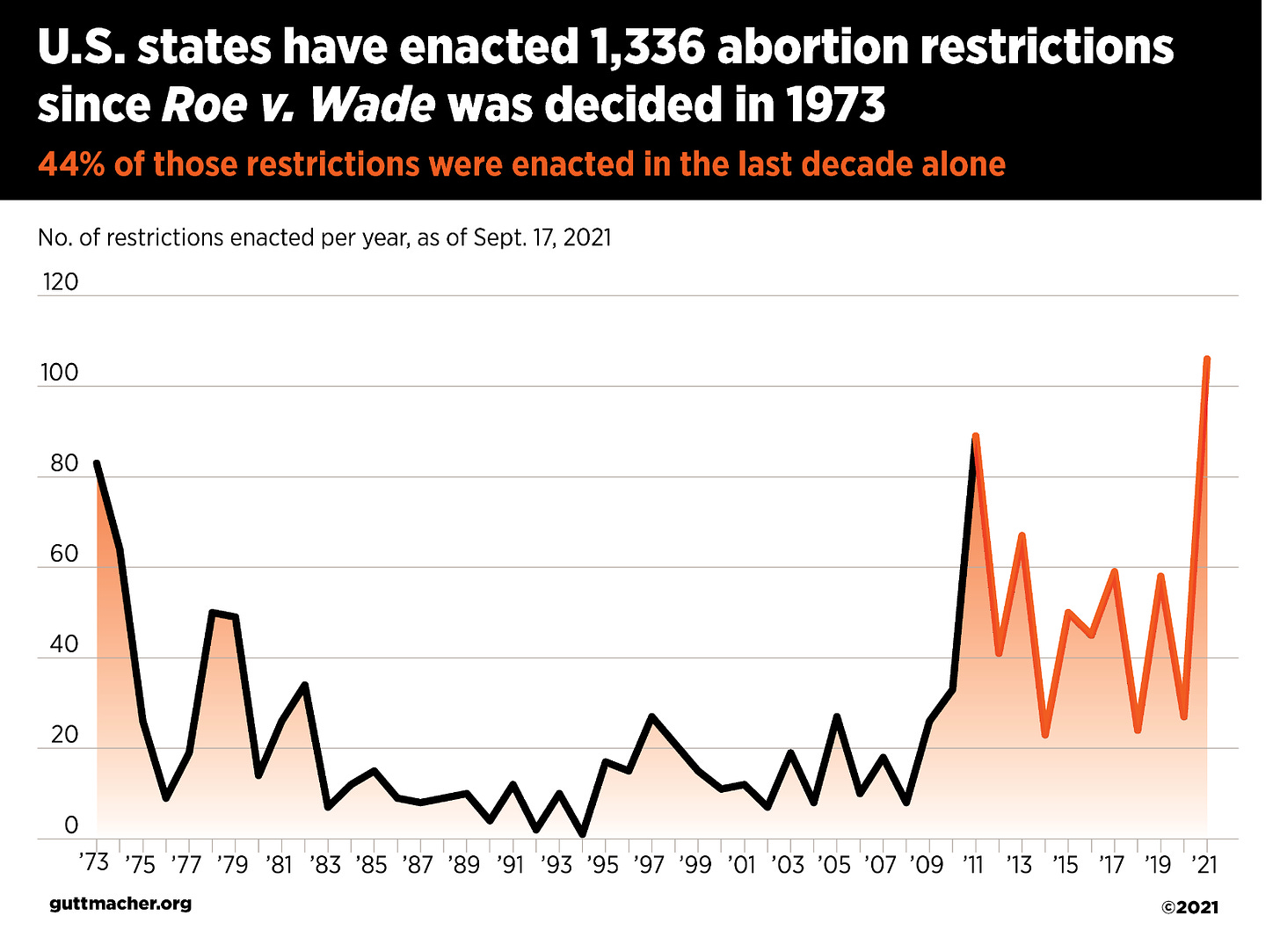

The 5th Circuit order tossed the claims from the initial approval of mifepristone decades ago, but allowed review of changes since 2016. Those changes made it feasible to get the drug for up to 10 rather than 7 weeks into the pregnancy, limiting the number of in-person visits required, and allowed non-physician health providers to provide the pills. The 5th Circuit claimed such changes were hardly crucial “given that the nation operated — and mifepristone was administered to millions of women — without them for 16 years.” The court ignores what compelled the demand for greater access to the drug, which was that state legislatures were closing off other means of access to abortion at an unprecedented rate. See the graph below from the Guttmacher Institute, tracking laws that had the effect of shutting down abortion providers and making abortions more expensive. Expanding the availability of mifepristone helped to partially offset these efforts.

The judges also accepted the standing claims. It is telling that the those bringing the lawsuit could not find a single woman who had taken the drug who would serve as a plaintiff. Instead, they rely on a group of doctors, including notable anti-abortion activists, who might experience a harm — “enormous stress and pressure” according to the 5th Circuit — but struggle to show that harm in any concrete way.

In separate pieces, Jonathan Adler and Adam Unikowsky eviscerate the standing claim, noting how the 5th Circuit relies on speculative rather than actual harms, ignores a clearly relevant opinion penned by a SCOTUS conservative majority, and employs shoddy statistical reasoning.

One wonders why the women who will be hurt by the decision are not considered. Giving declining access to abortion across the country, there will be greater demand for abortion pills. And yet, the “enormous stress and pressure” placed upon women who can no longer procure the least invasive and expensive means abortion does not merit consideration.

In a trick of legal jurisprudence, the courts have made the emotions that anti-abortion doctors express about a specific abortion drug more important than tangible harms imposed on women seeking abortions.

The 5th Circuit also shows an openness to Comstock Act claims. The Comstock Act is an 1873 law that outlaws the mailing “every obscene, lewd, lascivious, indecent, filthy or vile article, matter, thing, device, or substance,” or to mail any “thing” for “any indecent or immoral purpose.” It was broadly thought to be unconstitutional, but anti-abortion groups have sought to revise provisions that center on abortion. This has the practical effect of allowing broad criminalization of mailing abortion pills.

Most crucially, the 5th Circuit signals a willingness to overturn the judgement of the FDA on scientific matters. The FDA presented evidence that a) the drug has been widely used for decades in the US and elsewhere, b) there are “exceedingly rare” evidence of adverse effects, c) all drugs have adverse effects, including ibuprofen, but d) the FDA is asked to balance risk in relation to benefits, and on that basis there is no case for further restricting mifepristone. The court boils this down to “FDA’s principal contention to the contrary is that mifepristone is comparable to ‘ibuprofen’” — a claim it then dismisses.

This is another example of judicial pretzeling. Having bent over backwards to accept anecdotes and specious statistical reasoning from anti-abortion activists, the expertise of the FDA is dismissed, the evidence left unconsidered. The court faults the FDA for not initiating new studies after 2016, claiming this represents a violation the Administrative Procedure Act. But there is no requirement in the APA that the FDA perform such new analyses, the FDA could reasonably rely on clear evidence of safety across a mass population that had emerged at that point. Tellingly, the Courts cannot establish that the 2016 changes resulted in any tangible harm. But the court ploughs ahead anyway.

The Fifth Circuit seeks to establish that the FDA’s behavior was arbitrary and capricious using reasoning that can only be described as arbitrary and capricious. If this is different from Judge Kascmaryk’s original decision, it is different in degree rather than different in kind.

A regulatory nightmare for industry

What happens in abortion policy does not stay in abortion policy. Judges cannot neatly pull a Bush vs. Gore and claim that “[o]ur consideration is limited to the present circumstances.” They are establishing precedent that upends the regulatory landscape. The pharmaceutical industry released a statement expressing these fears:

If courts can overturn drug approvals without regard for science or evidence, or for the complexity required to fully vet the safety and efficacy of new drugs, any medicine is at risk for the same outcome as mifepristone.

This is not just whining from Big Pharma (who have provided disproportionate financial support to the Senators who voted to approve Kascmaryk). A group of scholars who study the FDA wrote an amicus curiae brief that issued the same warning:

If courts can unilaterally overturn safety and effectiveness determinations, manufacturers would simultaneously have to navigate a patchwork of judicial decisions regarding what is required for drug approval. This would fundamentally confound the expectations of industry, leave manufacturers vulnerable to challenges to their currently marketed drugs, and discourage investment in research and development of new drugs.

From a regulatory perspective, companies want simplicity and stability. The FDA process of approval may not be simple, but it is at least predictable. A process where any judge in the country can decide they know better destroys that regulatory stability.

According to Dan Carpenter:

…I would in fact be worried if I were a biotech company (they clearly are), because if this decision holds now anyone could go to court and either get a drug pulled off the market post hoc or, inversely, sue to get a drug under consideration approved immediately.

Think about the implications. All you need is a doctor who expresses some discomfort to act as a plaintiff, and a judge who is skeptical of a form of medication. It does not take much imagination to see how this could extend to contraception, or covid vaccines, medication for gender-affirming care or HIV prevention. This is not fanciful, since other conservative activists including elected officials have targeted such medications.

As Greer Donley and Rachel Sachs argue, the asymmetric right-wing drive to take control of medical regulation of groups viewed as undeserving has significant equity implications.

These concerns could exacerbate existing health disparities. The products most likely to be at risk are disproportionately used by women, LGBTQ people, those with substance use disorders, and other marginalized groups. These populations are already underrepresented in drug discovery.

And its not just the FDA and drug regulation. Unikowsky points out that by lowering the bar to standing will make any agency judgement subject to lawsuits by groups who do not need to show any harm.

Suppose an agency passes a rule that will increase the number of immigrants. Statistically speaking, an E.R. doctor will see an immigrant benefiting from the new rule at some point in the future which might divert resources from other patients, so apparently doctor organizations would have standing to challenge the rule. Now, suppose an agency passes a rule that will decrease the number of immigrants. Statistically speaking, some doctor in private practice somewhere will lose out on an employee at some future point that he hypothetically would have hired, so doctors can apparently challenge that too under the Fifth Circuit’s logic. I doubt the Fifth Circuit would actually reach these conclusions, they are too crazy, but this analysis merely underscores that the Fifth Circuit is applying unique rules to this case because it’s about abortion. Any judge can ban a drug nominally using evidence-based criteria that is the purpose of the FDA, but in reality using their own cherry-picked interpretation of evidence, drawing from activist organizations, and needing only a willing doctor to stand as plaintiff.

Fake concern about women’s health is still used as a means to deny abortion access

It is hard to engage in good policymaking based on dishonest claims, because sooner or later the falsity of the claims are revealed, and the credibility of the institutions that advanced them, and government more generally, is damaged.

One aspect of the pre-Dobbs world is the use of false claims by the anti-abortion movement. This was reflected in policies that sought to limit abortion by claiming they protected the health of the mother, e.g. by requiring medically unnecessary regulations such as ultrasounds, or specifying the physical layout of the buildings where women were treated. Such claims were at odds with the evidence and disputed by actual medical professionals. Yet key SCOTUS cases centered on whether the Judges were obliged to go along with transparent falsehoods about how policies that were designed to increase stigma or close health clinics would protect women.

This is the Big Lie of the abortion debate: that restricting abortions is motivated by a desire to protect the health of women.

Judge Kascmaryk continues this tradition, which provides a fig life of deniability to the reality that such restrictions have the effect of worsening health risks for women. He claims that lack of restrictions on the drug “resulted in many deaths” because the FDA “acquiesced to the pressure to increase access to chemical abortion at the expense of women’s safety.”

Needless to say, this claim is unsupported. Moreover, it is, not to put too fine a point on it, a lie, one that endangers women’s health.

First, lets look at the evidence on the drug itself. Echoing the FDA, Professors David S. Cohen, Greer Donley and Rachel Rebouche describe the evidence:

To be clear, mifepristone is one of the most studied drugs in this country. The evidence shows that it is safer than penicillin, Viagra, and thousands of other drugs the FDA has approved. There is no evidence that the FDA acted improperly in approving mifepristone; FDA law scholars and government agencies, like the Government Accountability Office, agree. (If you want to read more about abortion pills, we have a forthcoming law review article available here that explains all you need to know.) So the medical basis for this argument is meritless.

Second, what are the health effects of limiting the drug? Amanda Marcotte notes that a ban would not actually result in a safer alternative for women, but less comfortable and more dangerous medication abortions.

Right now, the standard practice is for a patient to take Mifepristone, which causes the pregnancy to stop developing, followed by Misoprostol, which expels it. However, Misoprostol-only abortions are "incredibly safe and effective," Dr. Brandi continued, just "not our first choice." That's because Misoprostol-only abortions "have more side effects." She explained that "It causes people to feel really crampy and uncomfortable. It can cause people to throw up and have fevers." It's also more likely to result in an incomplete abortion, requiring a patient to return for more follow-up care.

If women are unable to access a medication abortion because of the limitation, they are left with two options. A later term and more invasive surgical abortion, or childbirth which has significantly higher medical risks for women.

Judge Kascmaryk also claims that: “Women who have aborted a child—especially through chemical abortion drugs that necessitate the woman seeing her aborted child once it passes — often experience shame, regret, anxiety, depression, drug abuse, and suicidal thoughts because of the abortion.” This is another deeply held belief of the anti-abortion movement, and there may be cases where it is true (though not so many that the a woman could be found to represent this claim in court). But the best evidence we have is that compelling women to pursue unwanted pregnancies is bad for their mental health, and exposes them to greater poverty, instability and physical violence.

Undermining administrative expertise has costs

The willingness of judges to dissemble about the straightforward outcomes of their decisions when it comes to the public values they claim to care about — the health of women in this case — starkly illustrates the cost of undermining the capacity of a less polarized and more accountable set of administrative actors like the FDA.

The sheer chutzpah of the decision may create a backlash. In the same way that people balked when they hear of unqualified political appointees politicizing science, the Harvard Professor Dan Carpenter thinks that the decision “might end up strengthening the FDA.”

The judge’s opinion is so audacious that it begs the question of why anyone in his position would ever think to substitute his medical expertise for that of physicians, or why we would ever have a society that was set up to evaluate medicines through district court procedures. And it’s going to raise these questions for many other FDA procedures. If the courts push back and do so strongly, and/or of different societal interests and organizations rally to the agency’s defense, it might bolster the FDA in the near to long run.

The FDA is not perfect. But if it errs, it can be sued, or its leaders can be hauled in front of Congress, and big failures will be front page news. It is designed to a) prioritize evidence and b) be subject to legal and political forms of accountability. It has a strong incentive to get the science right because ultimately that is all it has to stand behind.

None of these things are true of Judge Kascmaryk and the 5th Circuit. The form of judicial accountability they offer is no accountability at all. It is not one that credibly claims that the FDA got the science wrong. Rather, it asserts that the FDA is not allowed to determine the science in certain policy areas, which will instead be decided by a group of people with strong anti-abortion views, including a potential SCOTUS majority.

The people who complained for years about activist judges and unelected bureaucrats want their activist judges to replace those bureaucrats. This reduces both accountability and expertise. It blocks society from addressing real problems, and it does so via constitutional Calvinball, relying on inconsistent, unrestrained and faulty judicial reasoning. Deconstructing the administrative state may be an appealing theory when promised by Steve Bannon, or articulated by Federalist Society judges. Now that they can actually undertake that deconstruction, the costs are starting to become more and more apparent. Because sooner or later people will notice when your de-facto alternative to the administrative state is much more arbitrary, capricious, incompetent and incapable of doing basic things like protecting the safety of the public.