What will be the new normal for public health insurance after the Public Health Emergency ends?

Some useful research evidence on the effects of burdens and health

One of the most fascinating aspects of citizen-state interactions (for me at least) is the ways in which administrative burdens interplay with health. In America, we spend a lot of time and energy dealing with healthcare hassles, and those burdens lead to foregone care. This is true whether you receive health insurance from your employer, purchase it yourself, or are provided it directly through a government program, though the latter group face more hassles when it comes to simply staying on health insurance from one year to the next.

Two new papers add additional insight about burdens and health. The first shows the ways in which burdens limit access to health insurance for kids. The second shows that people with poorer physical and mental health struggle more with burdens. This new research can inform a looming crisis in America, which is the end of the Public Health Emergency (PHE) in 2023.

The end of the Public Health Emergency will see a lot of people lose health insurance

The federal government declared the PHE in the context of the pandemic, giving states more money but blocking them from kicking people off of public health insurance programs. This also meant that the thicket of burdens to get on those programs were temporarily removed. This has been good for increasing coverage of uninsured groups, and reducing churn of eligible beneficiaries cycling on and off the program.

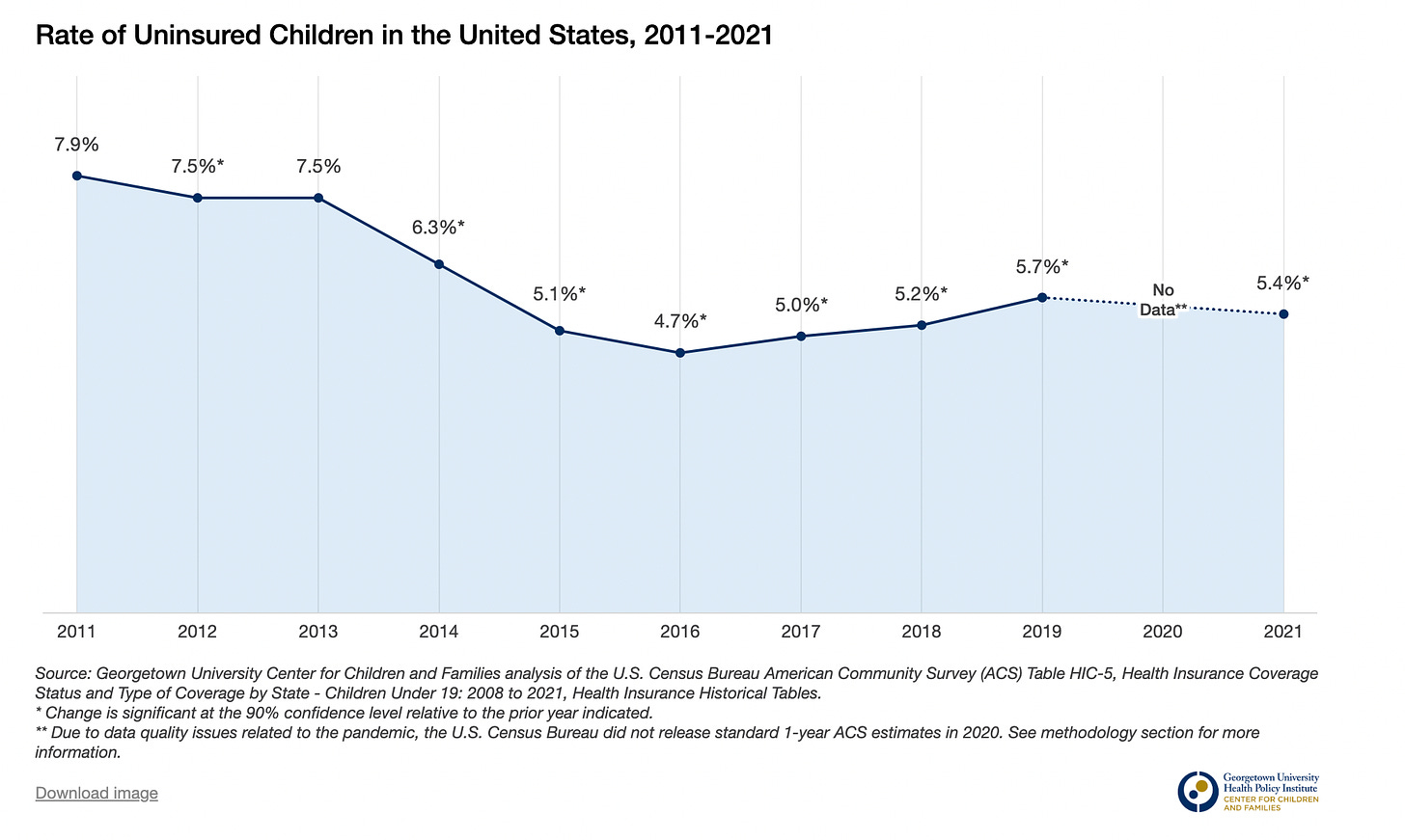

Step back, and the broader picture is that the US has been driving down the uninsurance rate over time, including during the PHE, with one worrying exception: the 2016-2019 period when progress actually reversed. This point is illustrated in a graph from colleagues at the Georgetown Center for Children and Families about the uninsurance rate for kids.

So what happens with the unwinding of PHE protections? Lots of people will suddenly face new forms and requirements they have not seen for a couple of years. And states will struggle to phase in huge new administrative demands: think of the collapse of Unemployment Insurance system during the pandemic when states could not manage the deluge of new applications.

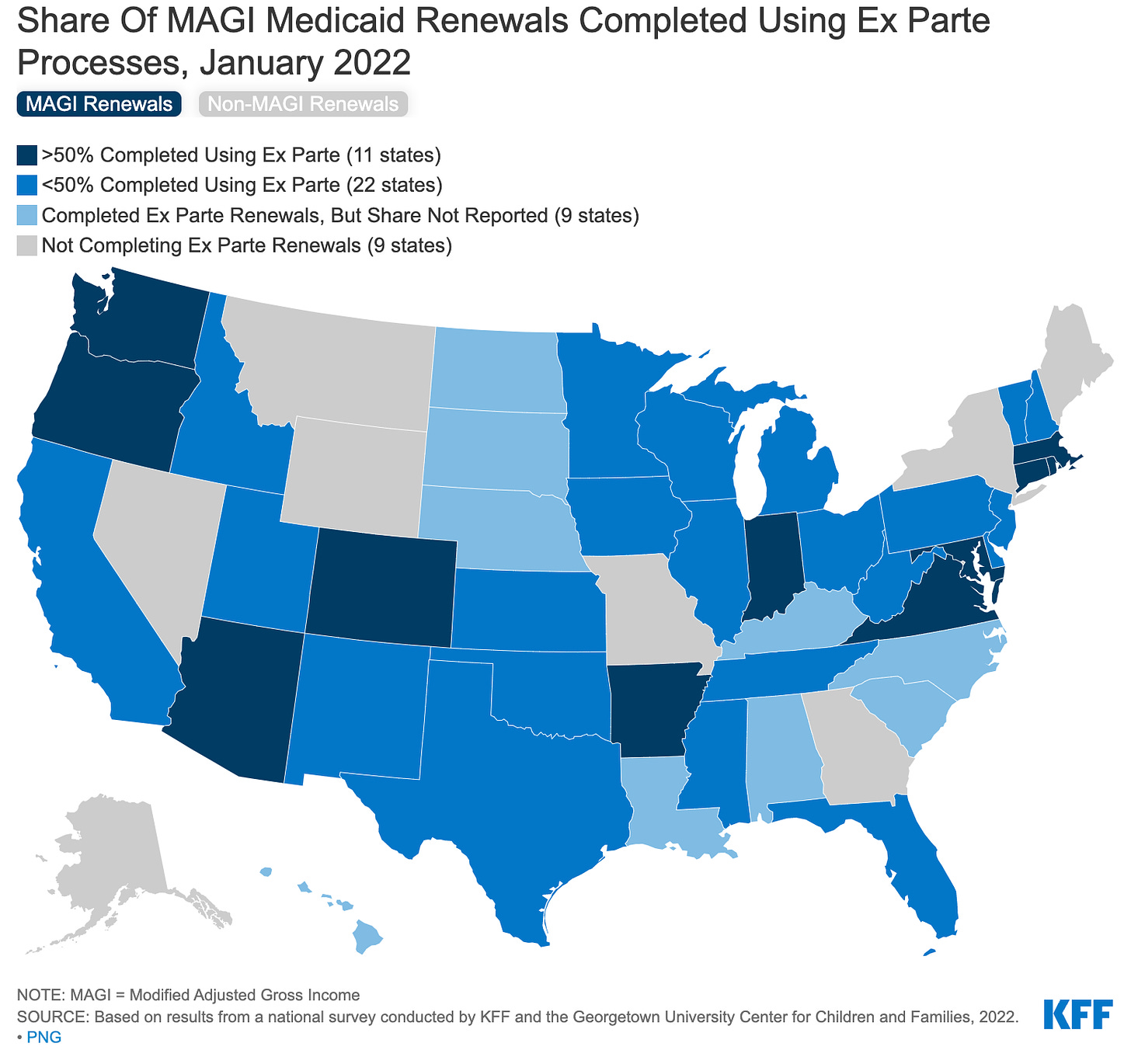

Of course, states know the end of the PHE is coming, and have been required to plan for it. But there are doubts about whether they are doing enough. For example, states could use administrative data to automatically re-enroll people who are clearly eligible ("ex-parte processes”), effectively shifting burdens from applicants and onto the state. But only 11 states report completing 50% or more of renewals using such processes according to data collected in early 2022 by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

This matters, because the evidence shows that small renewal burdens matter a lot, especially in health insurance, and that automatic renewals offer an effective tool to maintain coverage.

Administrative burdens in the pre-PHE era led to a decline in public health insurance for kids

Beyond this immediate shock of the PHE, what will the new normal of public health insurance will look like? What worries me is that it will look like the 2016-2019 period: states will return to imposing unnecessary administrative burdens on the public and the uninsurance rate will increase.

A new paper has examined the 2016-2019 era in greater detail, revealing the that state-imposed administrative burdens drove the loss in insurance coverage for kids.

The paper is released by NBER and authored by Iris Arbogast, Anna Chorniy and Janet Currie.1 They document new burdens created in each state, and how those burdens were associated with declines in enrollment, drawing on data from the American Community Survey to identify which groups were most likely to lose benefits.

They authors find that "increased administrative burdens placed on families reduced public health insurance coverage by a mean of 5.4 percent within the year following the implementation of these changes."

The authors use a variety of techniques to estimate these changes, but the basic story remains consistent. As new burdens are introduced, enrollment declines.

Some of these stories were already known, and their consequences predictable. For example, Tennessee saw 250,000 children lose coverage after it required families to re-enroll via a 49 page form sent in the mail. Many families never received the information, and the state kicked people off the program even when it had administrative data demonstrating eligibility.

Texas used information from credit-rating agencies estimates of individual income to assess eligibility. It did so for four consecutive months. If in any of those months income was above the allowed level, families had 10 days to prove income eligibility or lose benefits. Thousands of families lost coverage each month, but about half of them regained it, suggesting the process was screening out lots of eligible individuals.

As you ask people to jump through more hoops, they will lose coverage, regardless of their eligibility.

While the authors cannot generate a precise estimate, they conclude that “it is not the case that these administrative requirements acted mainly by weeding out enrollees who were in fact ineligible." In other words, states were adopting administrative processes that were causing eligible families to lose coverage because the families could not manage the paperwork.

Expect burdens to be more aggressively employed in red states

The PHE put a stop to these burdens, but states will be free to impose them when it ends. Where are such burdens most likely to return? While not a focus of their paper, the results seem consistent with observational evidence that the loss of coverage was higher in red states. Republican Governors are also the ones pushing for the end of the PHE, reinforcing concerns that they will use the type of burdens employed in 2016-2019 to cut Medicaid.

Burdens were harder for some groups to overcome than others

The NBER also paper provides evidence of distributive effects, i.e. that burdens fell heavier on some groups more than others. One important implication is that administrative arrangements that are nominally equal in their design and implementation can result in unequal outcomes because of differences in people’s situation.

The standard economics argument on this point, framed as ordeal mechanism, is that differences in outcomes reflect differences in preferences. The person who does not want to deal with administrative hassles simply does not need the benefit very much. This argument does not work so well in the context of health insurance. For one thing, we are collectively better off if as as many people as possible are covered. For another, public health insurance for kids more than pays for itself in future benefits.

Setting those objections aside, the ordeals perspective also misses the point that that unequal outcomes reflect differing ability to manage administrative processes, not just differing tastes. People with more educational and social resources will be better equipped to negotiate complex administrative processes. Those living in conditions of scarcity — they lack time or money — have less ability to focus on short-term administrative requirements that might generate long-term gains

Arbogast, Chorniy and Currie find that declines in insurance coverage amidst state-imposed burdens were three times greater for children without a college-educated parent, three times larger for Hispanic children, and four times greater for children with a non-citizen parent. The especially large effect on Hispanic and immigrant families likely reflects the intersection of state and federal policies (Trump's public charge rule) that combined to make an especially unwelcome environment for immigrant families seeking benefits.

Poor health makes it harder for people to overcome burdens

So burdens limit access to health services, and presumably better health. But it is also possible that people with poor health are less likely to overcome burdens.

A new paper in Public Administration Review co-authored by Julian Christensen, Elizabeth Bell, Pam Herd and myself(!) shows that people with physical and mental health challenges are more likely to report higher experience of burdens, and less likely to receive public benefits as a result.

We argue that health is another form of human capital that matters to how we engage with burdens. There is already some evidence on this point. Those with more severe disabilities are more likely to not seek disability benefits when a Social Security office closes. People with poorer physical and mental health are less likely to vote.

In our analysis, we focus on four specific health conditions: physical pain, anxiety, depression, and attention disorders in the form of Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD). These conditions are relatively common. Just two forms of pain disorders (headache disorders and lower back pain) and depression have been the leading causes of disability across the globe for the last three decades. An estimated 284 million experience anxiety disorders, 366 million experience persistent adult ADHD, and 73 million experience ADD.

To understand if health mattered in different settings, we looked at two cases that represent very different kinds of state-encounters (tax reporting and a means-tested financial benefit program targeted at low-income students) in two very different countries (USA and Denmark).

Attention disorders and pain are consistently associated with more intense reported experiences of administrative burden as well as lower take-up of benefits.

Our first case was tax reporting in Denmark. Actual tax reporting is pretty easy, certainly compared to the US, but the government asks that people update personal information. Failure to do so might create tax over- or under-payments that must be remedied later. Here, we found that the experience of pain, anxiety and the status of ADD and ADHD is associated with a greater subjective experience of the administrative process as burdensome.

In the second case, we examine student financial aid in Oklahoma. Unlike the first case, which did not offer an actual tangible financial benefit, here participants might earn a large benefit—state support that makes higher education affordable—but face a complex and intrusive administrative process to do so. Again, we found that pain, anxiety and ADD/ADHD were associated with higher experienced burden, with pain and anxiety also associated with lower take-up of benefits.

The effects of ill-health are cumulative

Modeling health effects is difficult, because they do not occur in isolation to one another. If you are experiencing pain, you are also more likely to be experiencing depression. To reflect this we examined the effects of multiple health conditions on the experiences of burdens. We found that those with multiple health problems have the most burdensome experiences in both cases, and lower levels of benefit take-up in the Oklahoma case.

The implication is that examining the effect of a single heath issue in isolation offers an incomplete picture. Instead, understanding the impact of health on the publics' ability to negotiate state processes requires attention to comorbidities.

Implications:

States need to commit to burden reduction as the new normal as the PHE ends

The pandemic was a period of giant experimentation when it came to the delivery of public services. As with any experiment, some things went well, and some did not. It is important that we learn from both success and failures. One lesson in particular is that many of the administrative burdens in health insurance were both consequential and unnecessary. The state can do a lot more to help people by permanently relaxing eligibility requirements that exclude far more people than they should, and by using administrative data and other tools to keep eligible families enrolled. We are now at the point where states need to pro-actively make that choice. If they don’t they are choosing to return to the 2016-2019 period where lots of needy families will lose help.

Target extra help to those with significant health problems

Collectively, the findings raise concerns about the human capital Catch-22: when it comes to administrative burdens and access to public benefits: those who are most in need of assistance also may struggle most to manage administrative processes. Therefore, policymakers and public managers can help by a) reducing burdens as much as possible for all with simple processes, and b) targeting extra help to groups who we know will struggle more, including those with significant health issues.

Currie is one of the OG scholars of administrative burden. Her work in thinking about why people do not take up social benefits was enormously influential on my writings with Pamela Herd.