Using automatic renewals to reduce Medicaid coverage loss

Early evidence from Minnesota offers a model for other states

Pam Herd and I wrote in Slate about how some Governors (cough - DeSantis - cough) are making zero effort to stem massive Medicaid coverage loss at the end of the public health emergency, but how some states are doing better, and what can be learned from them.

You can read the full piece here, and it is excerpted below. Full disclosure: Along with Professor Sebastian Jilke, we are working with The Better Government Lab to evaluate the effect of interventions to broaden access to the safety net that the civic tech nonprofit Code for America is enabling across states. Some of this will hopefully turn into academic papers down the line. But some of it has real policy relevance now, and so we want to share what feels like a promising and feasible innovation for state governments interested in reducing Medicaid coverage loss.

Florida Is Trying to Kneecap Medicaid. Blue States Can Do Something.

Pam Herd and Donald Moynihan

America remains the only well-off democratic country without universal access to health insurance. The 2010 Affordable Care Act, informally known as Obamacare, substantially increased access by offering Medicaid coverage to millions of low-income people who were previously denied coverage.

Progressive efforts in recent years to grow the effects of the ACA—such as by adding a public option—have failed to gain traction in Congress. During the pandemic, however, the government made a seemingly minor bureaucratic change that had a radical impact on insurance rolls. Typically, people have to re-enroll in Medicaid every year to show they’re still eligible. The federal government suspended this renewal process at the onset of the pandemic, meaning people would not be disenrolled for failing to complete the required paperwork.

The result? Simply not requiring Medicaid recipients to complete an annual renewal process saw a greater increase in health insurance coverage than Obamacare had over an equivalent time frame.

The lesson? Onerous administrative procedures are a key reason why even eligible Medicaid recipients lose coverage. Finding ways to reduce the administrative burdens in those processes—or better yet, to automate them so eligible clients never have to complete forms just to keep health care coverage—would be a major step toward ensuring people can access health care.

This lesson is especially important because an estimated 7 million eligible Medicaid clients are about to lose their coverage. Now that the pandemic is over, as well as the pandemic-era federal rules preventing automatic disenrollment, states are reinstating those renewal procedures. More than 1.6 million people have already lost their Medicaid coverage, and most states haven’t even begun these reviews. This is a slow-moving and largely preventable administrative disaster in the making.

Eligible beneficiaries are once again encountering unwieldy bureaucratic obstacles to keeping their coverage. Some states have done little to prepare for the great unwinding, despite persistent warnings. Florida has dropped more than 300,000 residents from Medicaid since April. Nationally, 71 percent of disenrollments are occurring due to “procedural reasons,” like missing paperwork, or simply because notifications were sent to an old address so people didn’t realize they needed to recertify.

Red states were quick to begin disenrollment once the public health emergency officially ended. This fits with a long-standing pattern of Republicans strategically using administrative burdens as a form of “policymaking by other means” in health and welfare programs. For example, Florida is just one of two states, along with Montana, that has declined to use any of the flexibilities offered by the Biden administration to minimize the effect of the great unwinding. But blue states, like Maryland and Connecticut, are also experiencing high rates of disenrollment for procedural reasons. Political motivations aren’t the sole source of burdens. A lack of capacity, innovation, and technology also matters, and importantly, can be fixed.

Indeed, there is some good news from the front lines. Some states are implementing practices to reduce the risk of catastrophic coverage loss.

Automatic renewal, referred to as “ex parte renewal” in the context of Medicaid, means that clients avoid needless paperwork and maintain coverage. And state officials spend less time, and money, on administration.

Processes of automatic renewal rest on a fairly simple premise: When the state has the data to verify that a client is eligible for a program, it should go ahead and renew them, rather than ask them to repeatedly provide that data.

In some policy areas, states have become more willing to apply this principle, such as in automatic voter registration, or using data to register people in other safety net programs once they have demonstrated eligibility for one program. But it is not used as effectively and aggressively as it should be as a standard policy tool for a variety of reasons including outdated views around privacy concerns in this area.

A more pressing challenge is the administrative and technological capacity required to move to a new approach. Minnesota, like many states, uses ex parte renewals for some clients whose eligibility is based on income, ultimately processing 25–50 percent of renewals this way. But to help manage the great unwinding, they recently expanded to another population: the aged, blind, or disabled. This required retraining employees, developing new approaches to compiling and presenting eligibility data to employees, and automating some of the most repetitive parts of their job, such as notices sent to employees.

About 70 percent of the state’s 200,000 aged, blind, and disabled qualify for a new ex parte renewal process, and of those, preliminary analysis shows 85 percent will be auto-renewed. This means that more than half of the most vulnerable Medicaid beneficiaries will be spared an onerous administrative process, as well as the substantial risk of losing coverage. Assuming that ex parte renewal protects 10 percent of people who would have been rejected for procedural reasons, this results in an extra $636 million in benefits.

Tools like ex parte renewals offer a win–win when it comes to reducing burdens. They reduce administrative barriers for clients who no longer have to complete confusing forms and provide complex documentation. They also help caseworkers, who no longer have to chase down missing documentation or deal with renewals when clients realize they have lost their coverage, which generates an estimated $500 per case in administrative costs.

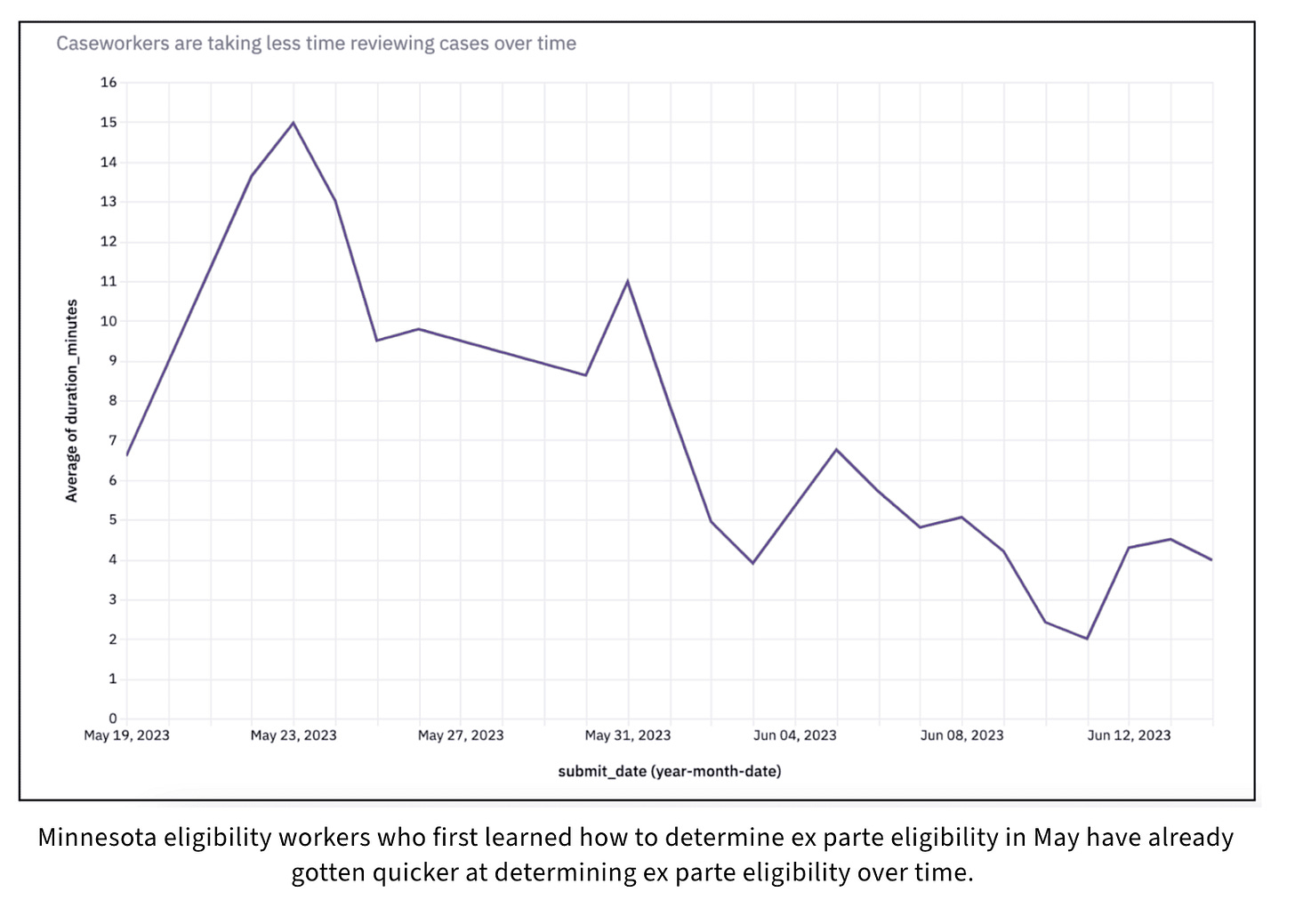

It also saves time, a resource in short supply amid the barrage of renewals. In Minnesota, state employees spend an average of 70 minutes on a standard Medicaid renewal process, but ex parte renewals took a fraction of the time—about 10 minutes per beneficiary as caseworkers learned the new system. This translated to about $4.6 million annually in the value of caseworker time saved, allowing the state to direct that time to more complex renewal cases.

For state leaders, more aggressively employing ex parte renewals should be a no brainer. The Biden administration has been pushing such tools, and surveys of the public show that almost 7 out of 10 people support using automatic renewals to maintain coverage. The end of the public health emergency offers a moment when state governments can re-imagine how they manage their relationships with citizens. Expanding the use of ex parte renewals would reduce the expensive “churn” of recipients cycling off and on programs, as well as the time both they and state officials spend on paperwork. It would show the public that their government is ready to innovate to help them, rather than willing to settle for outdated processes that drown citizens in paperwork.

If you are interested in learning more, take a moment to read a blog from Nalleli Martinez and Ashley "Tez" Cortez of Code for America and Jennifer Wagner on the Center of Budget and Policy Priorities. Again, excerpts below, where they get more into the nuts and bolts of the intervention.

Building Human-Centered Benefits Renewal Processes with Client Equity in Mind

Lessons from piloting expanded ex parte renewals

Nalleli Martinez, Ashley "Tez" Cortez, and Jennifer Wagner

Policy and dated legacy systems do not have to be blockers. We started with a two-county pilot, and then later a four-county-pilot. At each stage of the process, we worked closely with county and state workers in policy, operations, and tech to understand how to roll out a process change in MAXIS, their legacy benefits management system from 1989. In both pilots, we held working sessions, giving county eligibility workers the opportunity to troubleshoot through live cases with Minnesota Department of Human Services (DHS) policy and operations experts in the room.

We can say that it’s absolutely possible to build and pilot human-centered processes in legacy benefits management systems—if the right people are on board for the change. We regularly met with policy and operations experts at the state level to align on creative ways to interpret policy during the development of the ex parte process. Building side-by-side with caseworkers who understood the intricacies and complexities of the process allowed us to turn their feedback into process improvements and ensured we stayed aligned with requirements and constraints. We were surprised to find that the state’s legacy system, although dated, was adaptable. This made it easier to develop automated notices and other efficiencies to streamline processes and save worker time.

Pre-determining and identifying the ex parte eligibility pool speeds the process. During the pilot, county leads identified and pulled cases for the renewal month and had to manually check each case to see that it fit certain criteria. It took a lot of time and energy to evaluate whether each case would be eligible for an ex parte renewal based on certain state issued criteria.

To make this process simpler, we worked with Minnesota IT Services (MNIT) and DHS policy and operations experts to develop policy guidelines for identifying cases likely to be successfully renewed ex parte. From there we supported the creation of an automated list of eligible cases per renewal month, removing that time-consuming burden from the county. Now, the state delivers a monthly report to counties ahead of the renewal timeline that indicates which cases the counties should try to renew ex parte.

It’s necessary to write clear policy and operational documentation to support caseworkers in processing renewals for people with complex cases. The hardest moment for a caseworker is when they come across a case where the details don’t align with any instructions or policy they’ve been given. During the pilot, we worked side-by-side with counties and the state to develop clear process guidance with edge cases in mind—for example, what to do if a client moves out of state between phases of the enrollment process. Code for America shared process guidance in multiple formats including a worker-facing website, a training deck with step-by-step guidance and screen shots, and a recording of a case walkthrough that met rigorous Medicaid privacy standards. Looking ahead to the statewide rollout, DHS is using these learnings to provide training and materials that will support caseworkers in processing renewals for complex cases.

Minnesota eligibility workers who first learned how to determine ex parte eligibility in May have already gotten quicker at determining ex parte eligibility over time.

Strategically leveraging automation eases administrative burden while increasing accuracy for clients and caseworkers alike. During the pilot working sessions, Code for America staff noticed that the majority of caseworker time was spent manually producing a notice that would be sent to a client alerting them of their ex parte renewal. In a legacy system where word processing has not matured since 1989, this was a long and tedious process. It also introduced the possibility of human error—for example, a caseworker manually inputting a client’s name into a notice could accidentally share another’s personal identifiable information.

Automation is ideal for workers, because it makes for an efficient process and ultimately gives them more time to work on their caseload or other work while eliminating risk of manual errors. We worked with MNIT, as well as DHS policy and operations experts, to create state- and federally-compliant approval notices that clearly inform clients their Medicaid had been renewed, and to develop an approach that generates a notice when a worker identifies the case as ex parte eligible.

The impacts of these changes:

Clients are successfully renewed and relieved of the burden of navigating the confusing renewal process. These people are no longer susceptible to benefits churn—meaning they won’t experience a lag in critical access to medications, doctors, or other medical needs.

Caseworkers now have more time to dedicate to more complex cases and are spending less time on cases that have churned through the system.

Office support staff are no longer spending time supporting the intake and tracking of renewal paperwork—and can instead spend that time on new enrollments.

The right moment for scaling renewal work

Minnesota isn’t the only state facing an impending mountain of benefits renewal work—but we hope that our collaboration in this arena can serve as a beacon for states facing similar challenges. We know this work can happen in states with both legacy and modern benefits management systems, as long as the right stakeholders come together at the table to build an ex parte process with equity at the center of it. Dedication like that can help build an improved benefits renewal process for state administrators, caseworkers, and clients alike.

Thanks for another encouraging post! Are there reads you would recommend that tackle head on the issue of privacy concerns weighed against administrative burdens, toward improved government services and non-profit collaborations?

Nice example today in the NYT about Philadelphia slowing evictions simply by requiring tenants and landlords to seek mediation if the amount in arrears is under a certain threshold. Landlords get paid, fewer evictions, the rising tide floats pretty much all the boats, and it's a pretty simple tweak in process that came entirely from people in government who are involved in the process.