"No SNAP for you"

The petty cruelty of a new bill in Iowa, and what it signifies for the future the safety net

Iowa Republican legislators proposed a sweeping bill that would curtail the safety net for Iowans. Changes to SNAP (also known as food stamps) drew the most attention: SNAP users would be barred from buying staples like fresh meat, butter, vegetables, white rice, sliced cheese and flour.

The proposed legislation is infuriating on many levels. It increases learning costs for recipients who have to keep up with the whims of state legislators. Imagine that every time you shopped you had to know a long list of seemingly arbitrary items that you weren’t allowed to buy? It also adds to the stigma faced by SNAP users. It’s not unusual for SNAP users to end up at register being told they bought the wrong kind of cheese.

Where did this pettiness come from? Dig deeper and you find the list of restricted foods is based on existing policies for WIC users, which provides food supports for women, infants and children.

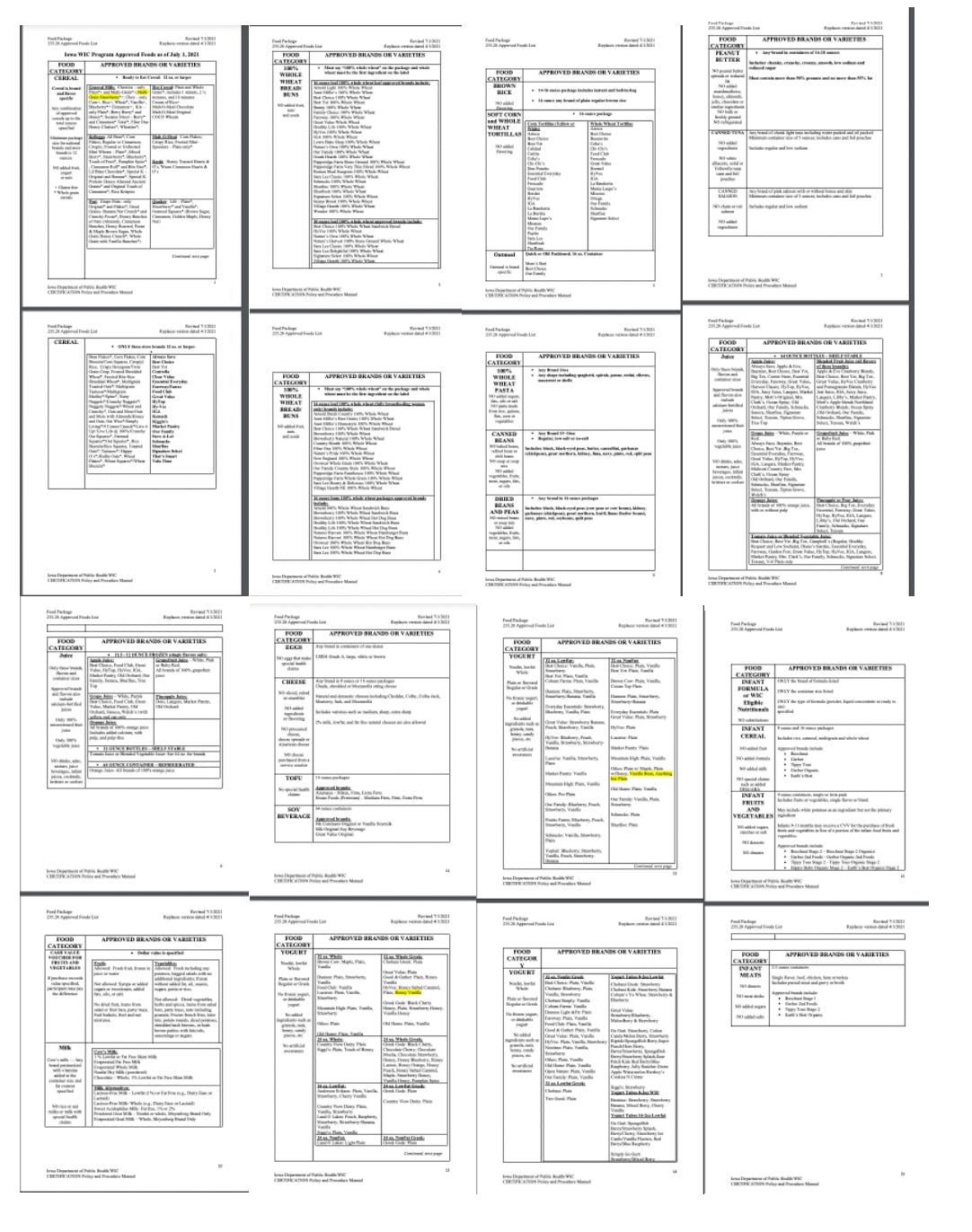

To give a sense of the learning and compliance costs involved, here is a visualization of the entire 16 page Iowa guidelines on what WIC, and now SNAP users, are expected to master.

Note that the guidelines don’t just restrict the types of foods that are allowed. Want to buy cereal? Only certain brands and specific cereals are allowed. Users also have to know their portion sizes. Cereals have to be more than 12 ounces. Some breads must be bought in 16 oz loafs, restricted to particular brands and types. Others must be 24 ounce loafs. Tuna can only be bought in 5 oz containers. Every page is a detailed list of what they are allowed to buy, drawing the inevitable comparison about what they can’t.

But this is for their own good? Right? Right?

Why the detailed food list? Proponents of such requirements rationalize that these guidelines will improve the health of mothers and their children. These lists will make people eat better, reduce obesity, and improve health, right?

Wrong.

The empirical evidence documenting obesity as the primary explanation for links between poverty and poor health is weak and the relationship between socioeconomic status, obesity and health is complicated. This is not to say that poor nutrition and metabolic disorders don’t matter for health, it’s simply that there’s little evidence that the solution to health disparities will come from focusing on obesity.

Further, many of the restrictions make little nutritional sense in practice. It’s hard to argue that restricting people from eating any kind of rice is good, or that canned meats are superior to fresh meats. And how does only allowing people to buy 5oz portions of tuna fish improve health? Indeed, the food lists reflect lobbying on the part of the food industry as much as health concerns. For example, the potato lobby objects to the exclusion of white potatoes from the WIC food list. Perhaps not surprisingly, Iowa allows for “any kind” of potato.

Most importantly, research shows that access to SNAP improves consumption of healthy foods and better health. As we detail below, these kinds of requirements mostly just limit access, reduce participation, and ultimately increase food insecurity and undermine health. Even when well intentioned, the actual result of trying to tightly regulate what people can eat makes them worse off.

The practical effect — and likely goal — of adding new burdens to SNAP is to reduce take-up

So what will happen if the bill is passed? Carolyn Barnes of Duke University does in-depth qualitative research about how people think about and use welfare benefits, including both SNAP and WIC. Her insights have changed our thinking about burdens by focusing on “redemption costs” — once people have a benefit, how easy is it for them to use it? Her research points out that there can be a lot of variation in these redemption costs that affect both participation in programs, and how people feel about them.

We asked Barnes about the likely effect of making SNAP as burdensome as WIC from the perspective of users:

In my work, beneficiaries of nutrition assistance have emphasized how easy it is to redeem SNAP benefits relative to WIC because there are no food restrictions. WIC participants, who also use SNAP, report trouble understanding what they can and can't buy with WIC and identifying "WIC friendly stores," (e.g. stores that keep WIC-approved foods in stock, label WIC approved foods, and train cashiers on how to redeem benefits). As a result, shopping experiences can be challenging. These proposed restrictions will create the same problem with SNAP. Right now, SNAP participants don't report stress and stigma in the store—just in the office—but they may soon if these restrictions are enacted.

In other words, it is burdensome to apply for and re-enroll in SNAP benefits, but has become relatively easy to use them. Innovations like electronic SNAP debit cards, or apps like Propel have helped. The proposed bill will make SNAP harder to use. WIC is not a model for SNAP to learn from. Indeed, while take up rates for SNAP are above 80 percent, take-up rates for WIC are closer to 57 percent.

The indefensible justifications

The bill has been sponsored by the House Speaker, Pat Grassley. So this is not one of those bills that sounds outrageous, but will never get out of committee. There is a good chance it will become law.

Speaker Grassley defended the bill by arguing that entitlements are at odds with other important goals, such as education:

If you look at the cost, if you want to look at a true budget impact on what things really are challenging in the budget for public education or private education, whatever it would be, it's these entitlement programs. They're the ones that are growing within the budget and are putting pressure on us being able to fund other priorities.

This is wrong for two reasons.

First, while some entitlement programs, like Medicaid, split the costs between states and the federal government, SNAP is federally funded. This is why even conservative state governments have generally welcomed SNAP, since it pours money into the state economy. It is also odd to emphasize costs at a time when Iowa is running an almost $2 billion budget surplus.

Second, if you care about education, SNAP is associated with better educational outcomes. Kids in families facing food insecurity do not learn as well. Kids in poorer families with SNAP are less likely to fall behind in school relatively to kids in the same situation without SNAP support.

SNAP also generates lots of other positive externalities that politicians should want. It reduces criminal activity, leads to better health and economic outcomes, provides a large economic stimulus, and lowers hunger and poverty.

The bogus nature of Grassley’s justifications is not unusual. As we have documented elsewhere, policymakers will often rely on defenses for burdens that fall apart on the slightest inspection. Why? Historically such burdens don’t receive close attention, being regarded as the dull details of administration. Here, the effort backfired, as the sheer pettiness of the food restrictions both defied common sense and increased the salience of the topic to the point that media gave unusual attention to the bill.

Snide side note: Grassley from Iowa? Yes, the primary sponsor of cuts that will impose the stigma of undeservingness on SNAP users is the grandson of Chuck Grassley. Senator Grassley can be seen swearing his grandson into office as Speaker, a position he earned entirely on merit.

The real reasons for such burdens? Political ideology, perceptions of deservingness, and paternalism

So what gives? Why make it harder to access a program that costs you nothing but makes your state better on many counts? Research points to political ideology and perceptions of deservingness. If we see a group as undeserving we tend to be more willing to impose hassles in their bid to access benefits. This is especially true for how conservatives think about welfare programs. By contrast, policymakers with direct experience of the hassles involved tend to be less supportive of them.

More broadly, paternalism, or the desire to control peoples’ behaviors, is endemic to most US poverty policy. It is rooted in the origins of the US welfare state, and is reflected not only in how we regulate food purchases for SNAP, but in the basic premise that instead of just providing poor people with a basic income to make their own choices about how to meet their needs, we create expensive and bureaucratic programs, ranging from food stamps to housing vouchers.

The fact that the Iowa GOP wants to ban SNAP users from buying American cheese is bizarre and petty. The fact that participants in the WIC program are already subject to these sort of nanny state restrictions should be a bigger scandal.

Will states increase or reduce burden in the post-pandemic era?

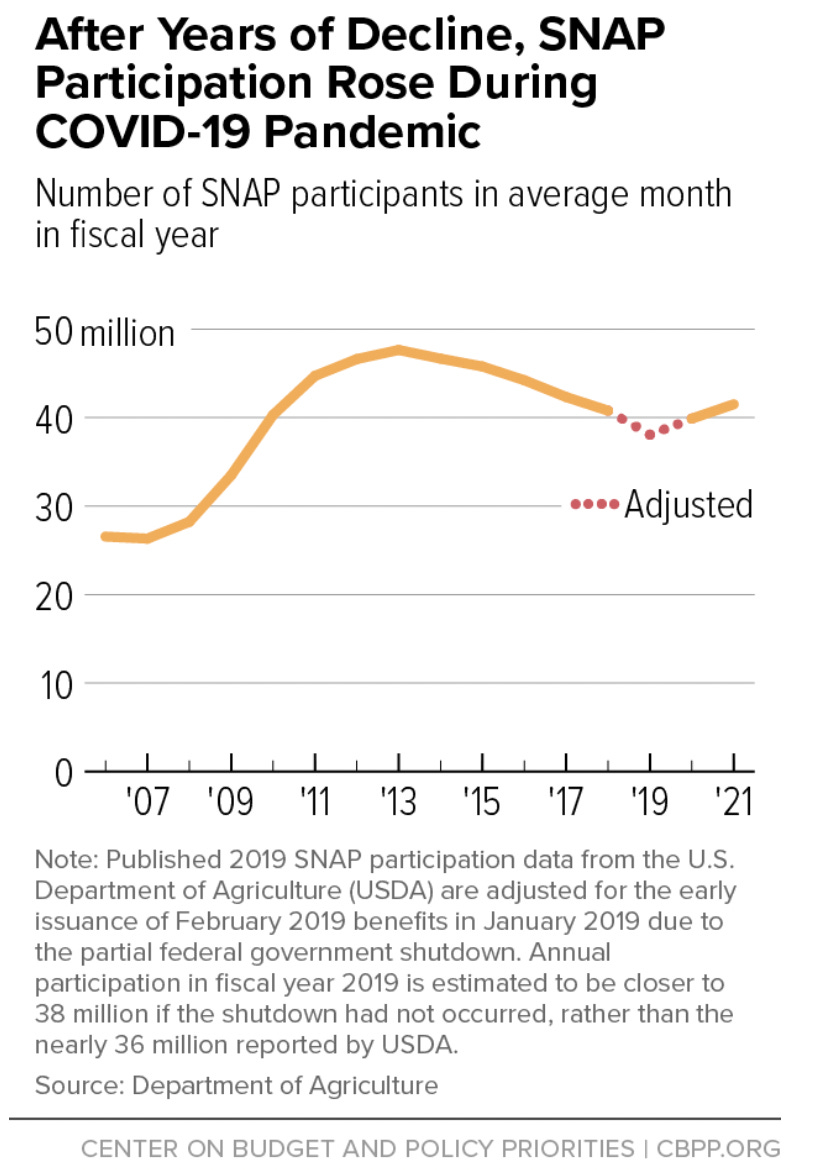

As the pandemic ends, we have an opportunity to rethink what the post-pandemic era looks like. Use of safety net benefits, like Medicaid and SNAP, increased during the pandemic, because Republicans went along with policies that broadened access and reduced burdens.

The pandemic paused Trump-era populist sentiment that SNAP was overused and needed to be constrained. The Iowa example illustrates that now that the pandemic is deemed over, GOP sentiment to constrain SNAP and other welfare benefits has returned.

Some decline in SNAP usage will occur if policymakers do nothing, and if the labor market remains strong. Some pandemic-era flexibilities to make it easier to keep people on SNAP, such as reducing the frequency of recertification, will end, also reducing participation.

States still have discretion about how to rethink their safety net. Iowa Republicans are using such discretion to make safety net processes as burdensome as possible. One relatively easy tell about the purpose of the Iowa bill is that in addition to the food restrictions, it also includes red tape that provides no functional value for its citizens but has a track record of reducing take-up among those who are eligible in both SNAP and Medicaid. The bill:

would enforce asset tests for SNAP beneficiaries: Very few people with low incomes and lots of assets seek public benefits. Asset tests therefore don’t solve a big problem. They are, however, effective at reducing take-up among those who are eligible because documenting assets is administratively onerous.

eliminate the state’s the ability to waive the 20 hour work requirement in SNAP for adults without children, including during recessions or for counties with high levels of unemployment. There is little evidence that these requirements will increase employment. Indeed, the resulting reporting requirements cause people who are working to lose their benefits. Combined with the the asset test, which extends to households with multiple cars, a basic requirement for workers in rural settings, the new bill discourages work.

requires Iowa’s Department of Health and Human Services to apply for a waiver from the federal government to impose a 20 hour per week work requirement for Medicaid beneficiaries.

tells state bureaucrats to seek a waiver to impose new burdens on Medicaid beneficiaries. The federal government requires states to use prefilled forms and to draw on existing administrative data to reduce frictions: if the government already has information about, for example, your income and number of dependents, it’s a pointless hassle to ask you about that information. Iowa Republicans are seeking to prevent state workers from using these burden-reducing tools that the federal government currently requires.

Such features make it very clear that Iowa Republicans are intent on making it harder Iowans to use these programs. Why else would you forbid state workers from making applications a bit easier to manage, especially in ways that likely reduce errors?

Other states can go in a different direction, drawing on lessons from the pandemic to reduce burdens. States can continue some pandemic-era flexibilities around interviews, a key source of reduced take-up and churn in SNAP. Many states switched from in-person to phone interviews during the pandemic. States can keep doing phone interviews, as long as they update their systems to meet federal requirements about how to authorize signatures and identities. Additionally, there are a range of ways, from doing on-demand interviews to improving scheduling options, to further reduce burdens and improve take-up and retention in SNAP.

The recent omnibus spending bill also included a seemingly small, but likely hugely impactful provision for Medicaid. States will be required to keep children enrolled in Medicaid for a year at a time reducing the need for recertification, a key source of people churning on and off the program.

Overall then, the federal government is offering a mixture of carrots and sticks to encourage states to learn from the pandemic in ways that will make the safety net more accessible. It will likely block some of the actions that Iowa is proposing. But it is hard to make administrative processes better when state leaders are determined to make them worse.

Excellent work, Pamela! It's more than a pity that policymakers ignore evidence, even when it is so plentiful. Welfare (to work) reforms in the mid-1990s shredded safety nets, yet requirements for assistance continue and are even being added. I was pleased that you briefly referred to a basic income guarantee as the obvious alternative to bureaucratic, paternalistic programs for the poor. I'd love to see more about that.