Why do we tolerate administrative burdens?

The role of ideology, personal experiences, and deservingness

Administrative burdens — the frictions we encounter in our interactions with government — are ubiquitous. Long lines, delays, confusing requirements, stress about processes.

So why do we put up with them? Why do we tolerate burdens?

These are not abstract questions. Some burdens may be inevitable in many policy areas. For example, determining who qualifies for a targeted program means an administrative process to verify both identity and eligibility. But in many cases burdens can be reduced without too great a harm. Indeed, the Biden Administration has enacted a program of administrative reform for just that purpose. By contrast, the Trump administration embraced adding new burdens, like work requirements, onto the social safety net. Such choices reflect politician’s assumptions about what their supporters want and desire. For example, Republican governors turned to work requirements in Medicaid in response to conservative voter beliefs about health insurance becoming too accessible.

So what do we know about burden tolerance? In the last couple of years, I and a few other researchers have started to answer this question. Most recently, with Aske Halling and Pam Herd, we published a paper (which is open access at Public Management Review) that examines what factors are associated with burden tolerance in SNAP (food stamps) and Medicaid, based on responses from a nationally representative sample of about three thousand Americans.

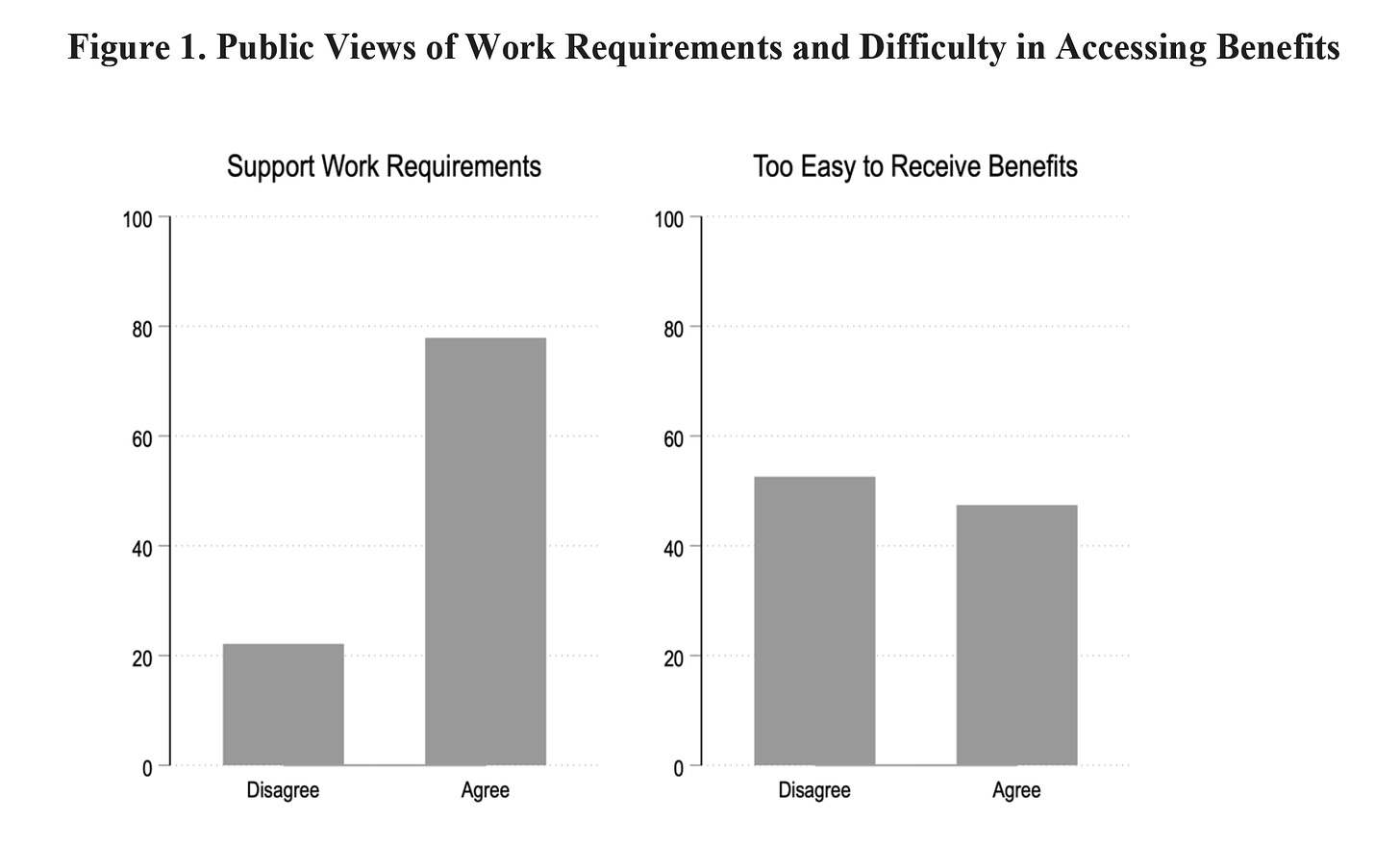

To assess burden tolerance, we asked people about the perceived difficulty in accessing benefits (‘It is too easy to get federal benefits like Medicaid and food stamps’), as well as support for a specific burden – work requirements – on recipients of those programs (‘Low-income adults who are able to work should be required to do so in order to receive benefits like Medicaid and food stamps’). The results were remarkably consistent.

So what did we find?

Support for work requirements, disagreement about how burdensome programs are

People are split in their views of whether SNAP and Medicaid are too burdensome, but there is stronger support for the specific burden of work requirements. Among the respondents who expressed a view, 79% either agreed or strongly agreed that low-income adults who work should be required to do so to receive benefits like Medicaid and food stamps, while 21% disagreed. A slight majority of 51% disagreed that it was too easy to get such benefits, compared to 49% who disagreed.

Such support for work requirements helps to explain why policymakers turn to them — think of Joe Manchin and the Child Tax Credit — despite evidence that they limit the reach and effectiveness of programs and are associated with decreased civic and political engagement. So it seems important to understand why people tolerate burdens.

Political beliefs: opposition to social programs and conservatism

Burdens can serve as a form of “policymaking by other means” — as a way of undermining policies that you oppose but cannot stop or eliminate. We found that as people expressed opposition to safety net programs more generally they also were more tolerant of burdens in Medicaid and SNAP.

Political ideology also matters. Conservatism makes people more opposed to social programs, for example. We found that even controlling for that opposition, conservatism still predicted support for burdens. This finding is consistent with prior research that shows that conservative politicians support burdens in welfare policies in Denmark, and that conservative bureaucrats support burdens in redistributive higher education funding policies they oversee in Oklahoma.

What we find implies that conservatism might make people more supportive of barriers in programs even beyond the effects of conservatism on their policy beliefs. In other words, conservatives have less of a problem with asking people to do more in state encounters. Some research suggests that personality traits associated with political ideology, like openness to experience, makes people more or less tolerant of burdens.

Personal experience

We also found that people’s policy experiences mattered. Those whose household benefited from redistributive programs were more opposed to burdensome processes. This might be down to self-interest, but it also may reflect people’s experiences. Policy feedback theory from political science argues that experiences teach citizens lessons about the political logics of policies, and their role in that logic. For example, direct experience of social policies educates people about how conditions like work requirements actually function: that they are excessively complex and demanding, psychologically draining, and do not serve their claimed purpose of increasing labor force participation.

Consistent with this logic, other research has shown that politicians who had received social benefits were more opposed to burdens in social policies, even ones they did not participate in. Another way of looking at this is that many people have little direct experience of how burdensome certain processes are — applying for welfare, or immigration services — which makes them blasé about the impact of imposing those burdens on others. This becomes a policy blind spot when we consider that policymakers and bureaucrats tend to be wealthier than the rest of the population, and thus lacking direct life experience of burdens associated with means-tested programs.

Deservingness

While we did not directly examine the issue of deservingness in our study, other research has, giving us good reason to believe that people are more comfortable imposing burdens on people they view as undeserving. This research typically uses experimental designs, varying the information about program recipients to make them appear more or less deserving, and then asking people to make judgements about how much burdens they should face.

For example, the study of Danish politicians found that they were more willing to impose burdens on those receiving unemployment assistance if told that they had quit their jobs. Another study found that people are more supportive of burdens in welfare programs relative to disaster aid, and less supportive of programs when they do not have high burdens on groups like former criminals relative to more deserving groups, such as military veterans.

Of course, deservingness may also be tied up in peoples racial views. One paper did not find evidence of racial solidarity in general when it came to imposing burdens, but but did find that White subjects were more likely to tolerate burdensome processes in vignettes that described White administrators dealing with Black welfare recipients.

Such findings help to explain why welfare programs, whose political framing emphasizes race and deservingness, are accompanied with high burdens. It also raises troubling questions about how to maintain equal treatment of citizens amidst an unequal distribution of burdens on populations who already enjoy lower political power.

More to read:

Our burden tolerance paper drew from survey data originally featured in a NY Times piece about the topic, which includes a very cool interactive quiz you can complete. Thanks to Margot Sanger-Katz, Emily Badger and Morning Consult for sharing the data.

The Center for American Progress published a fact-filled overview explainer about administrative burden and what to do about it. After years of neglect of this topic, especially among progressives, its good to see this sort of attention.

Pam Herd and I talked to Natalie Alms about why its so important to better measure people’s experience of administrative burdens.

I you enjoyed this, chances are you will enjoy reading the archive with posts about the Biden administration’s efforts to reduce administrative burdens, as well as new research on the topic. Please subscribe if you have not already, and consider sharing.