A pregnant woman in Texas nearly loses her life because the hospital doesn’t know whether the medical procedure to prevent rapid blood loss will qualify under the state’s vague ‘protect the life of the mother’ standard. A 13-year old rape victim in Mississippi is unable to access an abortion she is legally entitled to because exceptions to the state ban are too difficult to access. A single mother trying to use her food assistance benefits in Nebraska faces a wide array of restrictive food choices. She can buy a 12-ounce box of Cheerios, but not a 16-ounce box.

What do these people have in common? The answer is that both experience gendered burdens, i.e. coercive and controlling state actions that directly regulate gendered bodies, labor, and identity. Gendered administrative burdens are the administrative practices the state uses to enforce gender inequality—especially in regard to family.

Some argue that the state has not done enough to reinforce traditional family structures centered on marriage, with others decrying women for having fewer children as “demographic decadence”. Whatever one thinks of this diagnosis, it misses just how much gendered burdens coercively reinforce a specific type of family life, imposing more burdens and fewer choices on mothers who don’t fit into a kind of tradwife ideal, and generating racialized burdens in the process.

Everyone experiences administrative burdens in some ways. But women are more likely to experience them, in part, because of the gendered division of labor in families (which in practice means everything from dealing with the onerous safety net system for poorer women to the ‘cognitive labor’ of managing households). These types of burdens are growing, most obviously in the domain of reproductive care. The Dobbs decision repealing abortion protections reflects the influence of a White Christian Nationalism movement that embraces a greater willingness to use state power to enforce patriarchal ideals. The Alliance for Defending Freedom advocacy organization that coordinated the Dobbs case did so to “restore an understanding of marriage, the family and sexuality that reflects God’s creative order.”

Drawing on a new research paper in the Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory that examines gendered burdens in different domains, we highlight how these burdens control women’s bodies and reproduction, via abortion policy, and their care labor, via social welfare policies. Such burdens are not disconnected, but reflective of how burdens are used as tools to regulate and control women, especially racially marginalized women, including whether they have children and the family structures in which they have them.

Controlling Reproduction: Abortion Bans and Burdens

When abortion was protected by the Roe decision in the United States, administrative burdens were a key strategy used by anti-abortion opponents in so-called TRAP laws to prevent women from accessing them, a classic form of ‘policymaking by other means.’ States successfully imposed a wide array of different costs that made it very difficult to get an abortion. The limited women’s ability to control their own bodies, to choose whether and under what conditions they become mothers.

These burdens included learning costs, like requiring clinics to give women incorrect information about health risks associated with abortions, compliance costs, like waiting periods or medically unnecessary building requirements for abortion clinics that forced many to shut down, and psychological costs, which resulted from burdens like forcing women to have medically unnecessary vaginal ultrasounds.

Once states could simply ban abortions, wouldn’t the burdens associated with TRAP laws become unnecessary? In practice, however, the use of burdens around reproduction has become more widespread and is impacting far greater numbers of women.

The key issue is that abortion procedures, are in fact, a routine form of health care, one of the most commonly employed surgical procedures in the U.S. They’re used to treat miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, uterine bleeding, and for diagnostic procedures. Further, the drugs used for medical abortions, particularly mifepristone, are also used to treat illnesses, particularly Cushing’s disease and fibroids.

In states with new limits on abortion enabled by Dobbs, the resulting burdens have a broader scope than TRAP laws. Whereas in the pre-Dobbs era, burdens were targeted at women seeking abortions and abortion providers, now they are broadly applied to health care providers that follow standard medical procedures. Anyone who can become pregnant is newly vulnerable. Critical to the spread of gendered burdens, and their impact on women’s health, has been the criminalization of abortion, which can apply to both pregnant women and health care providers.

Nearly 20% of pregnancies end in miscarriage. But health care for miscarriages has become enmeshed in abortion bans. Woman have to show that a miscarriage was not, in fact, an abortion. A key source of burden is the ambiguous standard of proof applied; state actors may or may not accept evidence presented to them. Michelle Greenup, arrested in Louisiana after going to an ER with bleeding and stomach pain, was charged with second degree murder and imprisoned after hospital staff suspected she had given birth. Her medical records ultimately showed that she was not more than 15 weeks pregnant (so it was a miscarriage), and that she had received an injection that likely led to that miscarriage.

This cloud of suspicion has the most dire consequences for historically marginalized women. For example, among those charged under fetal homicide laws, present in 38 states, over half were Black women and 71% were low-income. Moreover, two-thirds of women charged were due to ‘risk’ of harm rather than actual harm, an even more ambiguous claim to disprove.

Providers are left to arbitrate ambiguous legal standards around key exceptions like allowing abortion to protect the health or life of the mother. As a doctor in Idaho noted, “There’s a lot of second-guessing and hand-wringing. Is she sick enough? Is she bleeding enough?” One physician argued that the “laws were designed to sow confusion and fear, and they're working. People want to stay out of trouble, and physicians are no exception to that.” Another doctor commented, “So you’re saying I have a 1-in-10 chance of spending two years in jail with a felony?…I got three kids. I mean, what?” At Supreme Court oral arguments about the Idaho law, Justice Barrett echoed the doctors concerns asking “What if the prosecutor thought differently” from the doctors? How hard would it be to find an expert witness willing to disagree with the doctor, and in doing so send them to jail. In such a scenario, the ambiguity resulting from such laws gives prosecutors, not doctors, with the final say in how physicians provide care for women.

The female members of SCOTUS highlighted the degree to which doctors would be second-guessed by prosecutors about what they were allowed to do under Idaho’s law. Nonetheless, the overall consensus is currently that the conservative majority believes the Biden Administration’s attempt to ensure women have access to emergency abortion access for to protect their health is unconstitutional: the federal government cannot compel states to protect women suffering extraordinary pain if the medical care needed involves an abortion.

If the Biden administration loses, there is no evidence that states will provide any clarity around health exceptions. Indeed, by some accounts it’s getting worse. For example, Texas’s Medical Board, which was tasked with providing clarification around when abortions could be performed, just issued guidance that only appeared to create more ambiguity and burdens. The Texas Supreme Court reversed a lower court ruling that would have provided more clarity. The confusion, it seems, is the point.

Not only did the Board not provide clear guidance on what practices were lawful, it recommended a series of documentation practices, that, as one physician noted:

are truly unworkable…The need for literature searches, attempts to transfer patients by any means available, documentation of how we determined a woman's danger of death or serious risks, the need for consultations or opinions of medical ethics committees, attempts at alternative treatments and determination of a woman's risk to support a particular method of termination. These are all incredibly cumbersome and time consuming.

The time consuming and bureaucratic processes are obviously dysfunctional in a context where physicians need to make decisions quickly—because if they don’t, women die or face irreparable damage, such as losing the ability to have children.

Not surprisingly, medical residents are increasingly avoiding states that prohibit them from protecting the health of female patients at the risk of prosecution. As a result, women in those states face even greater burdens to find care. States with abortion bans had a 10 percentage point drop in OB/GYN residency applications between 2022 and 2023, and more recent data points similar trends in 2024. Idaho lost 22 percent of its obstetricians in a 15-month period after their state ban passed in August 2022. Just half of Idaho counties have a practicing obstetrician.

Ambiguity around what actually constitutes criminal conduct around abortions is just one way that burdens matter. They’re also central to seeking exceptions for reasons other than health, such as rape, which often require extensive documentation and sometimes interacting with law enforcement, and have been left unused in practice for that very reason.

A Trump-led administrative state can add more burdens in other domains. This includes reinterpreting the Comstock Act, a law from 1873 intended to prohibit the transfer of “obscene, lewd or lascivious” materials through the mail to restrict contraception or abortion pills.

Controlling Care Labor: Social Welfare Policy

Women remain disproportionately responsible for children, even as their ability to choose whether or not to have them is weakening. Women are also left to manage much of the burdens in seeking social welfare policy supports. But women in married couple single earner households face fewer of them—and are less subject to bureaucratic coercive and controlling practices over their parenting.

The distribution of burdens in our social welfare benefit system makes it far easier to provide and care for children within married couple households. This is in no small part because the benefits to married couples carry far fewer burdens than those provided to single parents.

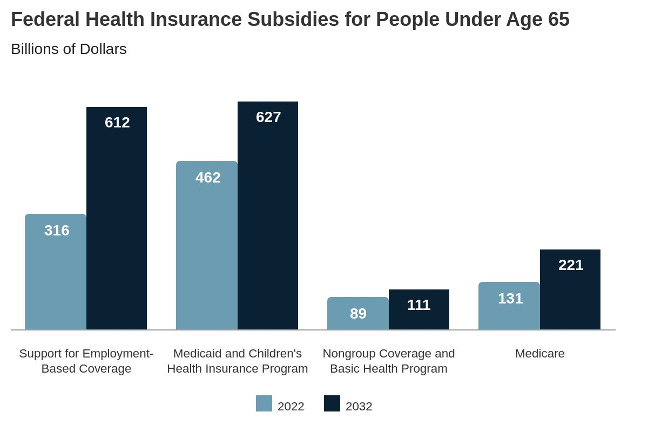

Let’s start with health insurance. Married women (and men) can access health insurance from their spouse’s employer. It’s a marital status benefit. And this insurance is subsidized by the federal government to the tune of $316 billion annually. Accessing the tax subsidy is so streamlined, many Americans don’t even realize they’re getting a benefit.

In contrast, those raising and caring for children outside of marriage, disproportionately women, are more likely to draw on Medicaid. The government spends roughly the same amount for both Medicaid and employer based coverage.

But unlike employer-based coverage, Medicaid comes with large burdens. Mostly mothers face lengthy eligibility forms, documentation, and the annual requirement to recertify, all of which enact huge costs. In the last year alone nearly 70 percent of those that lost their Medicaid coverage, almost 22 million people, did so due to ‘procedural’ reasons, like missing paperwork.

Other kinds of policies that also support caregiving for children, from food stamps (the SNAP program) to the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), all come with a wide array of burdens that affect access to the program—and ultimately the ability of largely women to care for their children outside of marriage.

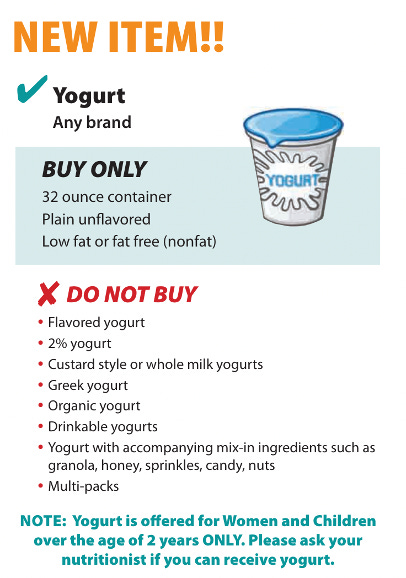

These programs can also be directly controlling and coercive. The WIC program, which provides food assistance to pregnant people and young children, tightly regulates what kinds of food can be bought. This 28 page booklet details what one can, and can’t buy. Actually navigating the grocery store with all of these requirements can be effectively impossible in practice. Here are the instructions for yogurt.

Social Security is the United States largest income support program, constituting almost one-fifth of the federal budget. It is also our least burdensome large social program (the government and employers keeps track of eligibility) and distinctly advantageous for trad wife (white) families. Eligibility for Social Security retirement and survivor benefits is tied to either employment or marital status. Over half of women receive benefits based on their marital status eligibility. To be eligible, one need never to have been employed, one needed only to have been married.

White married women disproportionately benefit. While over 90% of White women qualify for these benefits, just under half of Black women do. Moreover, the benefit design means that the households that benefit the most are one-earner households, which is more advantageous for White families given Black married women’s earnings constitute a greater fraction of household earnings than do White women’s. These benefits are designed to benefit married Women who stay out of the labor market.

In short, burdensome social policies make it harder for single women in poverty, disproportionately Black women, to receive support for their caregiving. The shift of the safety net supports to the tax system has reduced some of those burdens as long as long as single mothers engage in work, but their lot remains more onerous than for women in traditional family structures.

Burdens are especially coercive and controlling over racially marginalized women’s caregiving. If burdens condition access to supports needed to raise a family, they also directly constrain caregiving rights, best highlighted by child protective services. These services are a sprawling network of state surveillance and control, focused on disproportionately poor and racially marginalized women. As Edwards and colleagues note: “In many Black and Indigenous communities, being investigated by a child protection agency has become a routine part of childhood.” Social workers are not the only direct face of child protective services. There’s a vast army of mandated reporters, such as teachers or medical providers, who provide “eyes in the home” by surveilling children and caretakers for evidence of failure.

To provide a sense of scale and impact, 37% of all children experience a child protective services investigation with more than half of Black children versus 28% of White children investigated. It’s easy to fall under the eye of these surveillance systems, but hard to escape. Caregivers face a distinct array of burdens to extract themselves from the supervision of the state, including mandated participation in parenting classes, drug tests, and frequent home visits.

Administrative burdens are an opaque means by which the state uses power. This makes it hard to see them, and harder yet to connect them across multiple policy domains. We connect gendered burdens across multiple domains to reinforce the point that they are enmeshed in broader sets of (often implicit) assumptions about the role, rights and status of women. And many of them are designed to coercively support “traditional” family forms, with an implied pecking order where women are distinctly second to men. Identifying these connections is the first step in asking why they exist, and what can be done about them.

Excellent newsletter that highlights the systemic problems government has when dealing with women and children, especially when they are non-white. Gender "burdens control women’s bodies and reproduction, via abortion policy, their care labor, and social welfare policies. Such burdens are not disconnected, but reflective of how burdens are used as tools to regulate and control women, especially racially marginalized women, including whether they have children and the family structures in which they have them." These sentences succinctly sum up the issues. It should also be remembered that these burdens have been put into place by men, mostly white men, who do not directly suffer the consequences of their laws and policies. Most of our lives are controlled by others but we need to remember the importance of voting. Results aren't immediate but don't forget, it took a long time for the radical Republicans to overturn Dobbs. We have to persist.