Fewer burdens but greater inequality?

The implications of moving more of the safety net through the tax system

The past 30 years have been characterized by a radically shifting landscape in social welfare supports for American families, including both retrenchment and expansion of key income supports. A defining feature of this change has been an increasing reliance on the tax system To deliver social benefits. In a new paper in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, we think through what this means.

The good news is that the safety net programs that have been growing tend to have lower burdens. The bad news is that the most economically vulnerable Americans are clustered in programs that are shrinking and where burdens are growing.

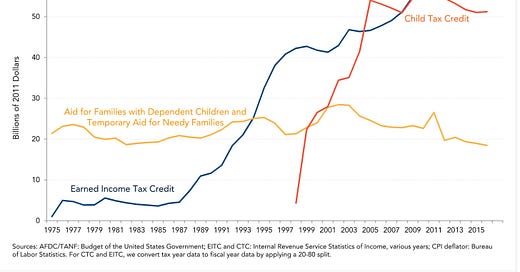

The figure below, though somewhat dated, gives you a broad sense of these changes. Traditional cash welfare (Aid for Families with Dependent Children and later Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) has flatlined, while two tax credits, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Child Tax Credit have grown dramatically.

Fewer burdens in targeted programs

A useful way of distinguishing between social programs is that some are universal (available to all in a broadly defined population) and some are targeted (only available to a specific population).

The idea that targeted programs are more burdensome than universal programs is almost axiomatic. Means-testing requires satisfying often paternalistic rules and requirements that can impede access to benefits. But changes to the U.S. social welfare safety net over the past 30 years complicates this narrative. On the one hand, means-tested programs, like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Program (SNAP), remain more burdensome than more universal policies, like Social Security.

On the other hand, key means-tested programs have seen significant declines in burden, which are reflected in rising take-up rates, even as, or likely because, eligibility for these programs has broadened.

One reason for this progress is that delivering benefits through the tax system has decreased burdens on average. The EITC, which subsidizes wages for low income workers via the tax system, has grown by over 30 percent since the mid 1990s and by some estimates substantially decreases poverty impacts for over 28 million Americans. One only needs to fill out the relevant part of their annual tax form. There is no extra bureaucracy, welfare office, or administrative process to deal with. De facto work requirements can be satisfied with tax documents collected directly by the IRS. People can complete the process with free tax preparation software or benefit from either free or paid tax assistance. Given this professional tax help, individuals eligible for the EITC and CTC generally access their supports via the tax system.

A traditional concern about welfare is the role of psychological costs, including stigma. Providing benefits through the tax system largely does away with this. There is no welfare office to visit, no concerns that an extra set of bureaucrats will treat you unfairly, or no incentive to play a role perceived to engender more sympathetic treatment. Claimants either fill out their own tax returns or work with a tax preparer who they can expect to treat them with the courtesy due a client rather than with the suspicion of an unwanted claimant. Because the benefit is tied to work, it is experienced as a tax refund that people feel they have earned rather than welfare. This has historical precedent. The idea of having ‘earned’ the benefit, was a key part of Social Security’s design and was intended to ensure the popularity and political sustainability of the program.

There is a strong case that expanding income supports via the tax system is an effective tool to reduce poverty. The expanded CTC offers the most compelling evidence here, but the EITC also matters a lot. Hoynes and Patel estimate that for every $1,000 increase in the EITC benefit there is a 9.4 percentage point reduction in poverty among families below 100 percent of the poverty line.

Even outside the tax system, take-up is relatively good for SNAP, a program that has grown in terms of size and generosity over time, with about 8 of 10 eligible individuals receiving the benefit, similar to the EITC. This take-up, however, has grown substantially since the mid 1990s when it was as low as 60 percent. This reflected consistent effort to reduce burdens by relaxing requirements around asset tests, in-person interviews, and allowing online applications, as well as innovations like the use of EBT cards.

It would be naïve to argue that targeting, on average, does not increase burdens. All else being equal, the more complicated the conditionality, the harder it is to reduce a program’s burdens. We’ve consistently argued that policymakers who want their policies to reach the people they are trying to help should avoid layering in more conditions.

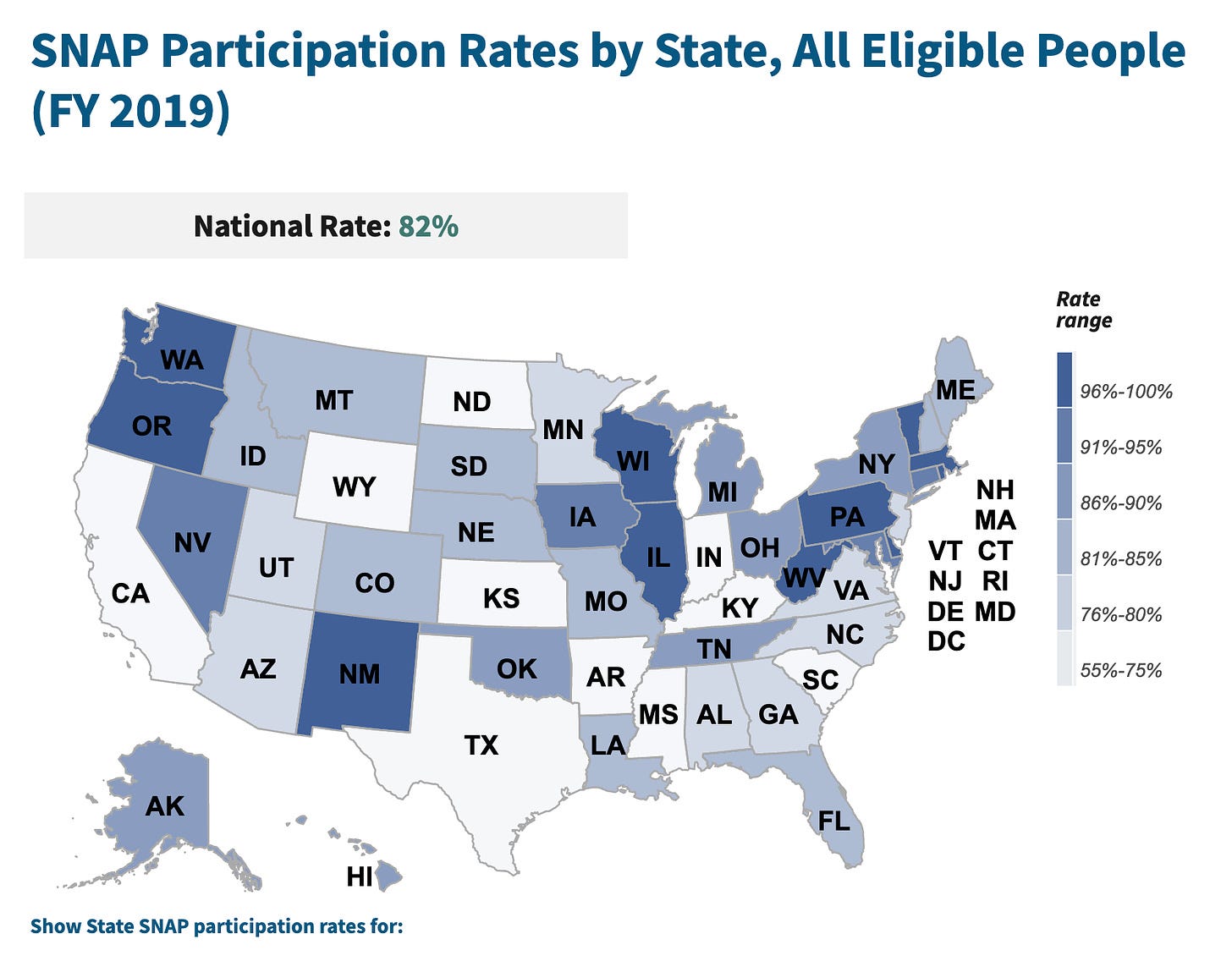

But debates over universalism and targeting can be simplistic—at least when it comes to burdens. The past three decades have shown that policymakers can, if they want to, maintain conditionality, reduce burdens, and increase access. Indeed, in states like Oregon, Washington, and Pennsylvania, SNAP take-up among eligible populations is nearly universal. There is reason to acknowledge and celebrate efforts to make these increasingly generous programs more accessible, since it means that on aggregate, those seeking support from the safety net can get more while dealing with fewer hassles.

Three reasons for inequality in the experience of burdens

At the same time that burdens have been declining on average, there have been increased inequalities in the experience of burden among beneficiaries. The source of these inequalities can be traced to three key factors.

Federalism

First, federalism in the U.S. has established a system in which the burdens safety net clients face vary substantially depending on geography. While the expansion of the EITC reduced this variation for those with high enough earnings, the creation of Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) in 1996 substantially increased this state variation, and related burdens.

The block grant nature of TANF allows states extraordinary discretion. According to advocates, this feature would encourage states to design and run programs that best suited their populations. But it also gave them significant incentives and resources to introduce burdens to limit cash welfare payments. As all states have funneled TANF funds into a wide array of different programs, such as job training, childcare support, and tax credits, they have created a confusing web of services and supports—often run by private contractors, including for-profits—that make the benefits and services opaque to those trying to access them. Indeed, only 22% of TANF dollars are spent on cash assistance. In five states, nearly 90% of applicants for TANF are rejected—even as states have accrued nearly $5 billion in unspent block grant funds. State “laboratories of innovations” are often just generating new ways to restrict access to help.

Unlike TANF, SNAP remained a federal program with significant federal oversight. But SNAP was not immune to burdens, which fell more heavily on people in some states than those in others. State variation in participation rates is significant, and here the relationship between a state’s political ideology and take-up is not straightforward. Take-up is high in states like Oregon (98%), Washington (99%), Wisconsin (92%), and Florida (86%). States with some of the lowest participation rates include California (70%), Minnesota (77%), and Mississippi (71%). The explanation for this variance seems to be structural. Devolution generally increases burdens, and both California and Minnesota administer benefits at the county level and consequently see reductions in take-up and increases in administrative costs.

Relying on the tax system

The shift to the tax system has reduced burdens in aggregate but has also exacerbated inequalities in the experience of burdens in a number of ways.

Tax benefits like the EITC and CTC are clearly less burdensome than alternatives like TANF. By contrast to those claiming benefits through the tax system, those with lower incomes have to navigate far more complicated welfare programs, are often disconnected from the benefits of the tax system, and are at higher risk of burdens via tax audit processes.

Even those claiming tax credits have uneven experiences. Individuals who earn below a certain level (currently $12,500) are not obliged to return tax forms. Those with very low incomes often don’t file taxes and are therefore unaware they’re eligible for the EITC, or even if they’re aware, may have earnings from multiple jobs or self-employment that is difficult to document.

As a result, they face much higher challenges in accessing tax credits. Roughly two-thirds of those eligible for, but not receiving, EITC benefits, fall into this category. This problem became even more apparent with the temporary expansion of the Child Tax Credit to cover those with lower or no earnings. During that time, the IRS automatically provided benefits to families where it had prior tax returns. But those disconnected from the tax system had to claim a benefit via a separate and initially poorly-designed process. This helps explain why receipt of the expanded CTC was lowest among families with the most intense poverty. See the figure below from Zach Parolin and colleagues. Other analyses show similar findings: people with no earnings received only 58% of their eligible CTC dollars compared to 74% for those earning between zero and $5,000, 89% for those earning between $5,000-10,000, and 93% for those earning more than 10,000.

Even those claiming tax credits, however, have uneven experiences. The highest burdens for EITC recipients is not in claiming the benefit, but the potential to be audited. In 2019, 53% of IRS audits were conducted on those with incomes below $50,000, and 82% of those individuals had claimed the EITC. This audit pattern also disproportionately targets Black EITC recipients, a form of radicalized burdens. The current IRS leadership is promising to do better, and new resources allows it to better target higher income earners rather than EITC recipients.

Privatizing welfare service delivery

The growing privatization of social welfare service delivery, particularly after the 1990s, has had significant implications for burden. In short, when private actors manage and distribute benefits, burdens tend to increase, as do inequalities in their distribution. This phenomenon is evident with the administration of TANF.

The reliance on private actors to deliver TANF benefits is driven by two factors. First, the shift to block grants empowered states with a preference to privatize government. Second, TANF focused more heavily on the delivery of services—job training and childcare provision—rather than the delivery of cash aid, which has a better record in reducing poverty. Nearly 80% of TANF spending is on services. As a consequence, states turned to a range of nonprofit and for-profit agencies to deliver these services.

Broadly, the private delivery of services makes it difficult for beneficiaries both to understand what benefits they are eligible for and then to actually receive them. Individuals must work harder to discern the state’s presence in the system and to find points of entry. And so, a new learning cost is created. The reliance on private actors also fragments service delivery; because individuals must engage with multiple organizations, they run the risk of falling through the cracks between state, local, and multiple private and nonprofit actors. This fragmentation also affects service providers, who may fail to engage with one another. Moreover, the incentives for private actors may not be aligned with the interests of their clients. For example, to maximize their profit, for-profit providers may “cream skim” beneficiaries—that is, work with the easiest clients. In doing so, they are more likely to penalize and discriminate against beneficiaries even when they are meeting programmatic rules.

Will these patterns continue?

The broad pattern of change reflects what has been an under-appreciated consensus around parts of the safety net, which have become both bigger and less burdensome in the post welfare-reform era. Families who are earning some income have more support than in the past, and lower burdens. Those disconnected from the tax system are worse off, facing substantially higher burdens.

Will these trends continue? Progressives and a growing number of Democrats have gotten better at identifying burdens and prioritizing their reduction. The success of the expanded CTC in reducing poverty has reinforced the preference for the tax system as a means of achieving their goals. Republicans have more mixed feelings about expanding the safety net, and the degree of conditionality they would like to impose. But they prefer safety net tax credits tied to work to a range of alternatives, like traditional cash welfare, or increasing the minimum wage, and become especially open to expansions of tax credits in exchange for expanding tax cuts. (Which raises the question of how we actually pay for this in the long run). On the other hands, Republicans have also become more willing to fight for burdensome work requirements in big ticket programs like SNAP and Medicaid, and to give states more discretion to impose burdens. In the coming months and years, fights over the Farm Bill (which governs SNAP) and a potential return of the expanded CTC will be pivotal battles.

Excellent essay and a great discussion of the benefits and burdens of the different approaches for the safety net. The Internal Revenue Code (IRC) has long been used to provide both targeted benefits (different filing statuses, tax brackets, dependents, etc.) and penalties. Politicians learned a long time ago that if they want something funded they could go through the IRC without having to take a public stand for or against that something. That something is hidden in plain sight in the thousands of pages of proposed tax legislation. But, there are two problems with this approach. The Congressional staff writing and revising tax legislation sometimes tries to foresee every problem and write solutions into the law. This makes the law cumbersome and difficult to enforce since the English language is frequently not precise, jargon is used, and it matters whether a simple word such as "and" along with "or" are used. Many times the audits of lower-income taxpayers is due to innocent mistakes concerning how to comply with the law. Tax preparation software has helped and the new IRS free tax filing program (still in pilot stage) will also help. The other problem is the constant defunding of the IRS by Republicans which not only helps those at higher-income levels but hurts those at lower-income levels. I've always thought that tax law should not be written by anyone who hasn't prepared tax returns for at least two years. I think the same can be said for safety net rules. Politicians should shadow someone who needs these benefits for six months to see what's it's really like. Since I'm wish casting, I'd also like to see cities use some of the empty office buildings to build out one-stop shopping for citizens having access to multiple safety net services, SNAP, the IRS, Social Security, voter registration, DMV, etc., or even kiosks easily available for some problems. Unfortunately, no one is eager for me to run this part of the administrative universe.

"Families who are earning some income have more support than in the past, and lower burdens. Those disconnected from the tax system are worse off, facing substantially higher burdens." We learned from the American Rescue Plan experience with a fully refundable CTC that the tax system can be used to reduce poverty. I have proposed a negative income tax basic income guarantee at the poverty level ($15k/yr) for all adults. Unfortunately, as you noted, we are accustomed to imposing work requirements for welfare. We need to detach our sentimental attachment to this burden before we can have a rational discussion of significant cash assistance to the poor.