Rethinking welfare fraud

SNAP clients are having their benefits stolen; governments are slowly catching up

If you are poor in America, you become accustomed to the accompanying indignities that come with seeking help. The political debate about whether you deserve support, and the burdens that come with getting it. Some of those burdens reflect fears about fraud - the idea that you are ripping off the system. But what if welfare fraud makes the welfare claimant the victim rather than the villain? How does the state respond?

For one particular policy, SNAP (also known as food stamps), this is a real problem. SNAP users use Electronic Benefit Transfer cards, which look like debit cards with one crucial exception. Debit or credit cards issued by banks or credit card companies now have chip technology that makes them more secure. EBT cards don’t. If someone is using your credit card for suspicious charges, banks or credit card companies will flag and pause the transaction. Not so for EBT cards. And until recently, SNAP clients were on the hook for fraudulent use of their cards.

The popular stereotype of welfare fraud might still be the welfare queen, but it should be that of a sophisticated criminal gang, adept at using technology. This requires a change in perspective, where welfare clients are viewed as victims, with rights, rather than under suspicion. It’s not limited to SNAP. There are plenty of examples of fraud in our health care system, but the really large scale stuff is driven by organized gangs, providers or insurers, not individual clients. Unemployment insurance fraud during the pandemic was a real issue, but as Jen Pahlka notes, the fraud detection systems were often efficient at trapping eligible claimants in bureaucratic webs, but not well-organized gangs who were committing fraud on an industrial scale.

EBT card fraud

All EBT cards are currently magnetic stripe only, which are vulnerable to a particular kind of skimming fraud, i.e. when thieves place a device on an ATM or a retailer’s card device. Other new types of fraud involve phishing for card information from SNAP users, which can be then used with cloned cards. The more sophisticated scammers pay attention to the times when when states governments deposit SNAP payments, and use the card immediately after to maximize the amount stolen.

I know a fair bit about the SNAP program, but was unaware of this form of fraud until I listened to a This American Life episode called “The Runaround.” The story, based on a story published in the Baltimore Banner by Brenna Smith, is about Renee, who had thousands of dollars of SNAP benefits stolen. She and Smith try to recover the funds by finding the culprits. Even if you care nothing about SNAP, its a fascinating detective-story-meets-welfare-state mash-up, as Renee bounces between state welfare offices, administrative law judges, stores where her card was used, and police officers who offer little help. Ultimately, she proves that someone else stole from her, but to no avail. The state of Maryland was not obligated to cover her losses.

The story has a happy ending, of sorts. Policymakers actually did something about it. An omnibus federal bill signed in 2022 provided funding to cover losses from fraud, at least until September 2024. Losses are covered for up to twice the amount of a monthly benefit, and can be claimed up to twice a year. The law also directed the US Department of Agriculture (which oversees SNAP) to require state plans for reimbursement and for EBT security. The law came too late to help Renee, but maybe it could help others.

New processes - new burdens?

Unfortunately, word of security vulnerability has gotten out amongst fraudsters, and the issue is getting worse. When other credit and debit cards are protected, EBT cards become a more attractive target for criminals.

To help me understand this topic I spoke to Betsy Gwin and Deborah Harris who work at the Mass Law Reform Institute, and have been working on this issue. They sued Massachusetts over this issue, helping to direct attention to the problem. Now the state is setting aside money to cover all losses that SNAP clients encounter.

How big of a problem is this? We don’t know, but historically state agencies have been doing a poor job of tracking it.

We do not have national data, but we know that this is a national problem. Some states, like Massachusetts, were hit harder and earlier than other states. We know that $1.6 million in SNAP was stolen from via skimming between June 2022 to Nov. 2022. Approximately 7000 Massachusetts households were harmed in the last year.

In many ways, the state agencies administering SNAP have more access to data and ability to identify and track skimming-related theft than individual households. Many, though not all, skimming-related thefts are characterized by certain patterns. For example, state agencies can see when there are multiple balance checks on an account, followed by unusually large withdrawals (often draining all benefits from an account), or a rapid succession of transactions on an account from another, often faraway, state. Households are not aware of the transactions or thefts until they attempt to use their card or check their balance and find the benefits are gone. We’ve had clients standing in the grocery store line, attempting to purchase a week’s worth of groceries, who had to leave their cart behind when they swipe their card can find they have a zero balance.

Other snapshots from states hint at the scale of the problem. Internal Maryland government emails report that $12.2 million was stolen and $11.7 million reimbursed as of August. 22. California is expecting to cover losses of $178 million in the most recent fiscal year.

The key point is that governments need to rethink their approaches to fraud. After the recent legislation, the USDA is prodding state governments in certain directions. Since the USDA released their guidance to states in January on how to deal with reimbursing fraud loss, states have submitted their plans. They look similar in many respects, but have varying degrees of administrative burdens. SNAP clients generally have 30 days to submit claims, and must replace their EBT or re-pin their cards.

The process of claiming fraud reimbursements can be more or less burdensome depending on the state. For example, Texas does not allow phone or online claims. Ohio requires physical signatures which seems consistent with an approach that also invites claimants to submit forms via fax. Some states require that SNAP clients produce EBT transaction reports to prove theft, even though the state already has access to that data. Another crucial difference is when the clock starts on claiming lost benefits: from when the theft was discovered or when it took place. The latter approach, employed by states such as Louisiana and Arizona, gives clients less time. It is also possible to see bottlenecks forming around mail times where clients have just 10 days to return paper forms. It is important that USDA collect and share data that casts a light on the nature and effects of these administrative burdens.

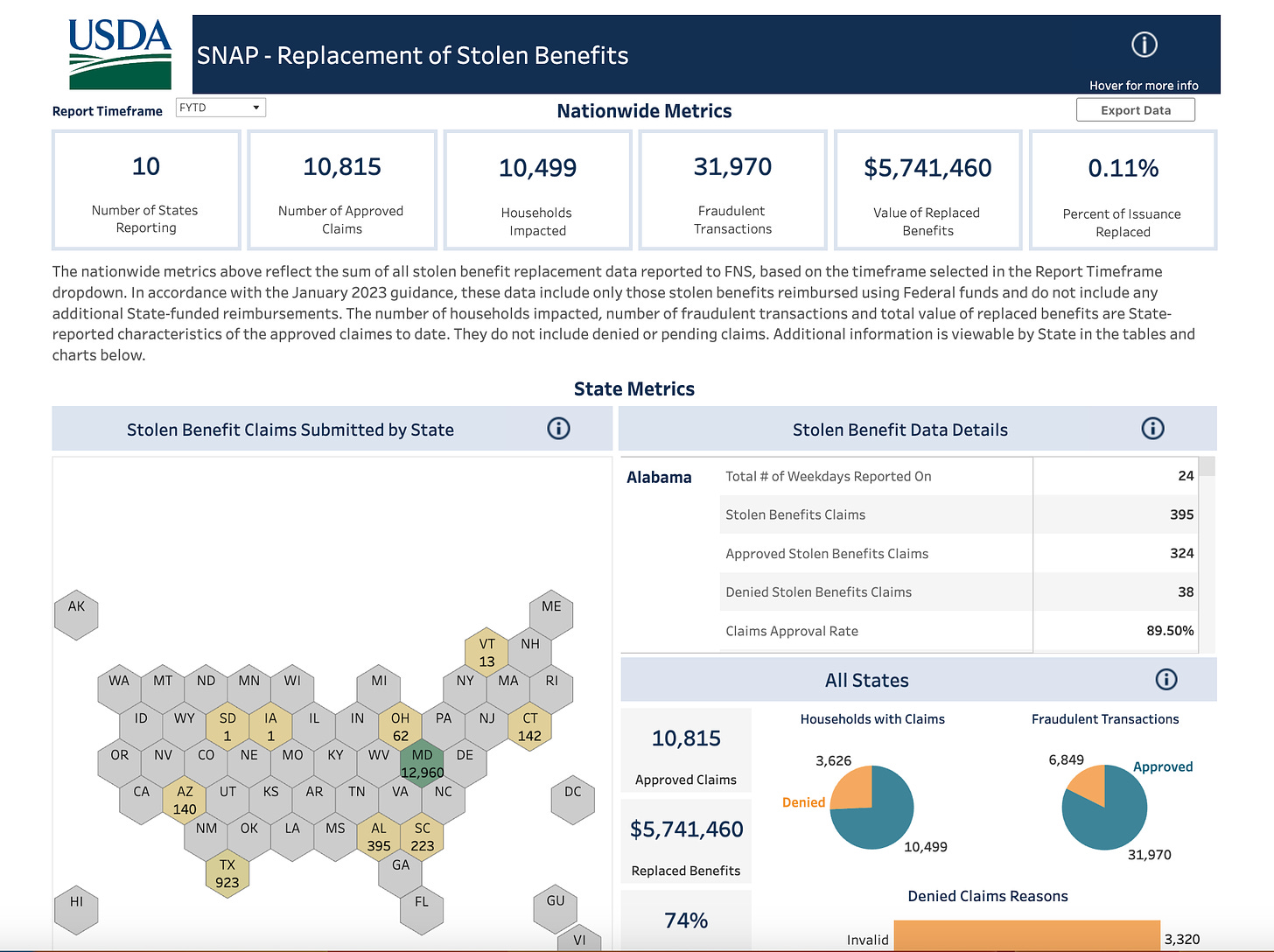

The USDA has created a dashboard, but only 10 states are reporting thus far.

Interestingly, the vast majority of claims are coming from Maryland. This may reflect that Maryland passed its own state law to supplement the federal reimbursement amounts, and was the first state to start doing reimbursements, partly because of stories like Renee’s. Continued reporting from Brenna Smith has pointed out that the USDA estimates of benefits reimbursed will likely rise and does not reflect actual losses.

Improving security

EBT cards could be covered by the Electronic Funds Transfer Act (EFTA), which would ensure that they cards must keep up with current market technology and security, as well as consumer rights to dispute potentially fraudulent claims. But EBT cards were excluded from these protections with welfare reform in 1996.

There are a couple of routes to fix this problem. One is that Congress will act, perhaps with the upcoming Farm Bill renewal. But we don’t have to wait. USDA could issue regulations allowing modern technology in EBT cards. The have been asked to issue a rule updating SNAP security policies, but this will not be released until late in 2024. States can also modernize by themselves. Governor Newsom has adopted chip and tap technology for California EBT cards, which may shift practices elsewhere. But its hard to make the case that any state should have exploitable security flaws. Instead, we need federal leadership to upgrade the baseline of security practices throughout the country.

One barrier to moving to better security is cost. At the moment EBT cards don’t have interchange fees charged by credit card companies. This makes them more attractive to retailers. Cards with chip technology do have such fees. So moving to chip technology could potentially increase the administrative cost of SNAP benefits. Retailers are calling for a carveout to avoid such costs for EBT cards. More than 40 million people use SNAP. It’s such a large market that it is difficult for retailers to simply abandon it, even with additional costs.

Currently, EBT clients do not have a legal right to their personal financial data that the rest of us enjoy due to Electronic Funds Transfer Act. This makes it more difficult for them to detect and rapidly report fraud. Making it easier for SNAP clients to monitor their financial data would help, and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau recently proposed a rule to facilitate access to financial data. The proposed rule is an improvement on what went before, but anti-poverty advocates say it does not move quickly or far enough to offer equal treatment for safety net recipients when it comes to their financial rights, or accessing comparable financial services as other card users.

Part of the underlying problem is that until recently no-one has been on the hook for losses, except for the SNAP clients. While credit card companies and banks have an incentive to closely track and minimize fraud, state and federal governments did not. The Omnibus bill puts the USDA and state governments on the hook, to some extent. They have to make some effort to track and cover losses, which gives them some incentive to reduce those losses. Fraud is not a violent crime, and Renee’s story in This American Life reflected a lethargic and uncoordinated police response. States reimbursing losses now have a financial incentive to target fraudsters and prevent fraud in the first place. But this means rethinking the existing fraud prevention framework to focus more on third party actors rather than clients.

California, for example, has created a special investigative unit to target this type of fraud. The chief of SNAP program compliance at the Los Angeles County Department of Public Social Services pointed out that he investigates 800-900 cases per month of people potentially claiming benefits they are not eligible for, which largely turn out to be negative. Meanwhile, several thousand people in LA are experiencing third party fraud per month which his team is not equipped to investigate.

At the broadest level, we might observe a story of halting progress. The adoption of EBT cards, replacing traditional food stamps, was intended to offer SNAP clients a modicum of dignity and convenience, reducing the stigma of welfare. As the security concerns with food stamps have arisen, both the federal and some state governments have responded to minimize losses, even if just temporarily, and not in a way that solves the problem.

A comprehensive approach would a) give SNAP clients the same financial rights as everyone else, including control of personal data and coverage for losses, b) modernize security protections on cards, and c) shift administrative resources to fraud protection that reflect the current threat. I worry that we might see a blue state/red state divide when it comes to covering losses, and that those opposed to SNAP will use increase in this new type of fraud to argue for minimizing the program rather than taking steps to solve the problem. But this should be a bipartisan issue. After all, no-one wants to see criminals steal public money intended to help people put food on their table.

I was not aware of the magnitude of this problem. Unfortunately, many of the "Christian" people in state legislatures and Congress do not have much empathy for people who need public assistance. They're stuck in the "welfare queen" world of Reagan, and note that the blame was placed on women in the system, especially black women. I agree with your solutions and the fact that administrative burdens should be kept as low as possible. Is there a phone app that people who receive SNAP benefits can use to check their balances, report fraud, and do other necessary things?