Fake Jobs and Fake Facts

By Misrepresenting Constitutional Law, Muskawamy Prove Brandolini's Law

Imagine you have earned science, engineering and business degrees from MIT and Oxford. You are interested in climate and sustainability, and so you choose to work for government. at the U.S. International Finance Corporation, as the Director of Climate Diversification. You are paid $172,000 per year, which is not bad, but likely much less than you could earn in the private sector.

And then Elon Musk, whom President-elect Trump has tapped to run the Department of Government Efficiency, says that you have a fake job, boosting a tweet from an anonymous right-wing poster that says you should be fired.

You have never met Musk. He has no idea what your job entails or whether you are good at it. The most likely reason he decided your job has no value is that “diversification” is in your job title, and Musk is too lazy to figure out that “diversification” and “diversity” are different things.

Ashley Thomas, the government employee in question, does technical work on how to make agriculture more robust under conditions of extreme weather. This seems like pretty important, with a classic public goods justification — the government is trying to figure out and share solutions to a problem that affects lots of people, and for which the market is unlikely to generate a solution by itself. Her organization’s diversification efforts include trying to expand the number of suppliers of battery metals that EV companies like Tesla rely on. Musk also attacked the chief climate officer of the Department of Energy’s loan program, which seeks to fuel green industrial development. Musk had no problem with the program when it gave Tesla a $465 million loan in 2012.

But of course none of this matters if you are fundamentally incurious about what government does, and absolutely sure that you know better. Your assumption that government is useless is so strong that you attack an office that is actually helping your business. That combination of ignorance and certainty is generally a bad condition for democracies, but a disaster when it characterizes whose who govern us.

To give a sense of scale, 33 million people saw Musk’s post. Ashley Thomas has since made her social media accounts private after the wave of online harassment from Musk’s followers. She is one of an increasing number of public officials who are learning that bullying and intimidation is part of the game plan for how the right governs now. She might reasonably infer that she will be fired from her job for no reason other than the fact that one of Trump’s courtiers wants to show that he can follow through on his threats.

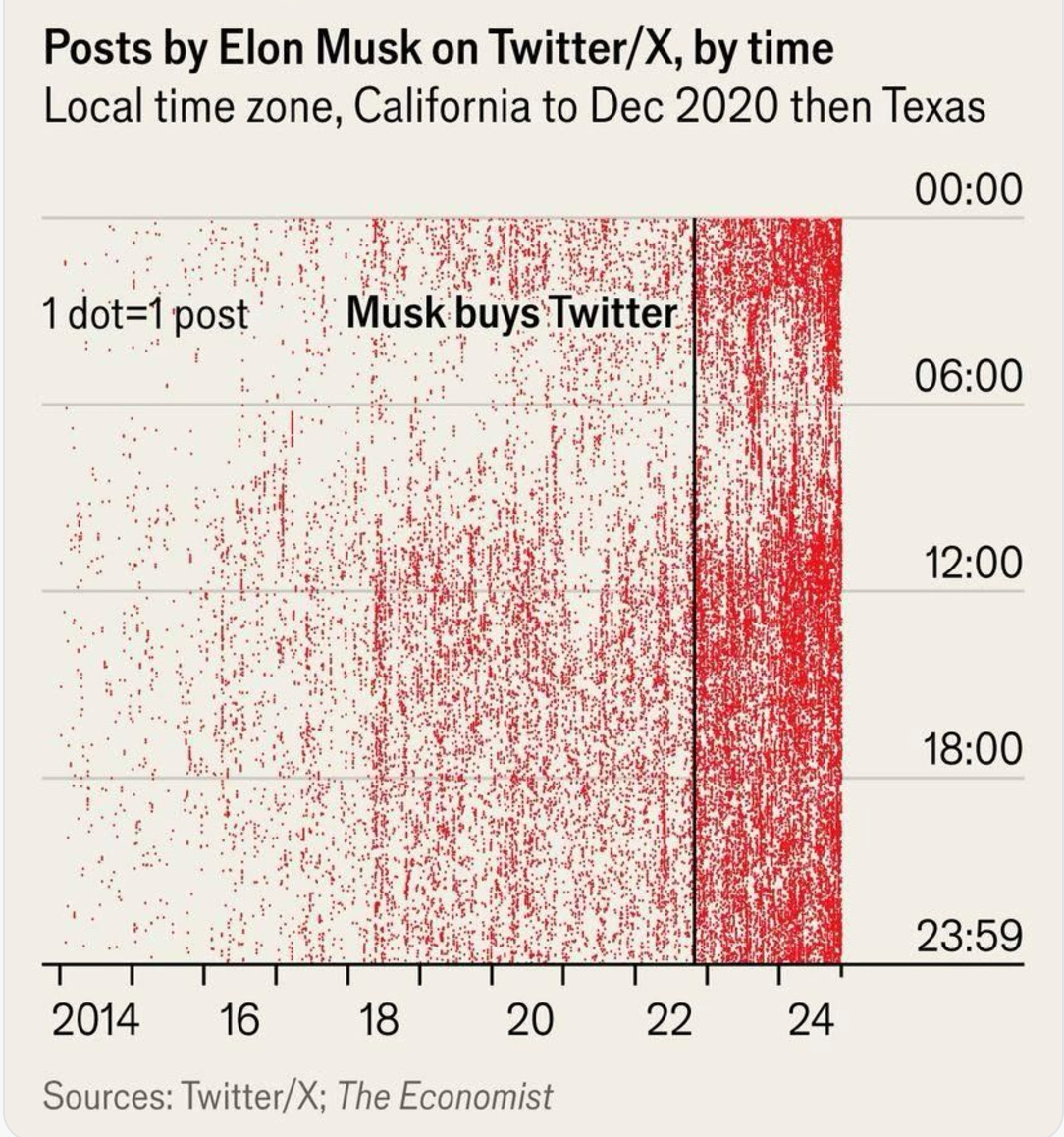

To provide a sense of perspective, would you hire a guy who spent this much time on social media?

If the answer is no, why on earth would you put him in charge of overseeing government operations that he is entirely ignorant of beyond his conspiracy theories, and conflicts of interests.

Outsourcing Public Sector Reform to People Who Hate the Public Sector

Of course, Musk is the one holding a fake job, since there is no real Department of Government Efficiency. In fact, we don’t really know what form his group will take. The obvious answer is that Muskawamy would serve as a Federal Advisory Committee, which is a standard way to structure input from outside advisors. But perhaps not. In an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, Musk and Ramaswamy say: “We will serve as outside volunteers, not federal officials or employees. Unlike government commissions or advisory committees, we won’t just write reports or cut ribbons.”

The problem with Federal Advisory Committees is that they must follow some basic transparency rules about how they operate. A shared belief between Musk and Trump is: “Transparency for thee, but not for me.” After railing against the corrupt deep state for years, Trump is refusing to explain who is funding his transition operation, a break with existing norms. Musk released “the Twitter files” to portray a (massively exaggerated) case that the website was co-operating too closely with the government. Now that he and his website helped to elect Trump and implement his policies, he has no problem with such close coordination. As Mike Masnick pointed out “Turns out for the “Twitter Files” crew, “creeping authoritarianism” isn’t so creepy when it’s your team doing the creeping.”

The Federal Advisory Committee Act has some persnickety language requiring fair balance and minimizing conflicts of interest, values that again do not score highly in the Trump or Musk worldview. Trump also saw some commissions he formed delayed and halted because they failed to follow these legal requirements, such as fair balance on a commission on law enforcement. Trump even issued an Executive Order to cut the number of number of Federal Advisory Committees in his first term.

For all of the above reasons I am increasingly skeptical that Muskawamy will operate under any kind of federal oversight or supervision.1 Instead, it will be an unofficial working group feeding ideas to the White House and Congress. Trump’s head of OMB, Russell Vought, has declared he will work with Muskawamy. But the Federal Advisory Committee Act is also supposed to extend to outside actors that agencies communicate with to avoid the type of shell game that Muskawamy seem to be pursuing. In other words, if Muskawamy are acting like a Federal Advisory Committee, they can be sued as if they are such a Committee, regardless of what they call themselves.

If I am correct, we are seeing what is effectively a privatization of government reform, where the richest man in the world is treated as a powerful Cabinet official while avoiding even the most basic forms of accountability that would come with the job. The Washington Post reports that Musk is not incorporating input from people who understand government, but instead is drawing from private sector billionaires who have been redpilled on Twitter and whose common interest is hostility to regulation:

Top Musk surrogates from his business empire — including private equity executive Antonio Gracias and Boring Company President Steve Davis — are involved in planning, the people said, along with a coterie of Musk friends and Silicon Valley leaders, including Palantir co-founder and investor Joe Lonsdale, who funds a libertarian-leaning nonprofit dedicated to government efficiency; investor Marc Andreessen; hedge fund manager Bill Ackman; and former Uber chief executive Travis Kalanick. Ramaswamy, Musk and the Silicon Valley cohort plan to work on technical challenges to collecting data about federal employees and programs, which they believe is siloed in antiquated systems. Andreessen is acting as a key networker for talent recruitment, one person said.

Remember again that Federal Advisory Committees must have some transparency and fair balance, and minimize conflicts of interest, and you can see why I’m skeptical that Muskawamy have any intention of accepting such values.

At the same time, Muskawamy assume massively expanded executive branch power, a vision that seems mostly detached from the constitution, and in some cases from reality. Immediately after Muskawamy released a Wall Street Journal op-ed abut their plans, I was asked by reporters to comment on which parts of it would be implemented and which would not. As I started to do so, I was reminded of Brandolini’s Law: The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than that needed to produce it.

Muskawamy’s claims sound plausible enough. They cite court cases. They assert specific Presidential powers. Responding to this requires sinking a lot of time into investigating the claims, and explaining why they are wrong. I also don’t want to fall for two competing follies: assuming Trump has King-like powers and all that Muskawamy declares will come to pass vs. dismissing Muskawamy as a non-entity.

I won’t be able to go through everything in the Muskawamy op-ed in this post, but can offer some push-back on a couple of points, and hope to return to other aspects in a later post. Let me just start by noting that they declare that “The president owes lawmaking deference to Congress, not to bureaucrats deep within federal agencies” even as they seek to set up a policymaking body contrary to Congressional guidelines.

The President Cannot Make Regulations Disappear Overnight

Muskawamy promise a “drastic reduction in federal regulations.” To do so, they rely on the Loper Bright Supreme Court decision that overturned Chevron deference. To simplify a bit, the decision said that the courts, rather than federal regulators, have the final say on federal regulation, and that the Courts should not defer to administrative judgements in cases where Congressional intent is unclear. The implications of the decision are a very big deal. Even so, Muskawamy manage to exaggerate it, and the decision in West Virginia vs. EPA, saying that the two cases mean that:

…a plethora of current federal regulations exceed the authority Congress has granted under the law. DOGE will work with legal experts embedded in government agencies, aided by advanced technology, to apply these rulings to federal regulations enacted by such agencies. DOGE will present this list of regulations to President Trump, who can, by executive action, immediately pause the enforcement of those regulations and initiate the process for review and rescission.

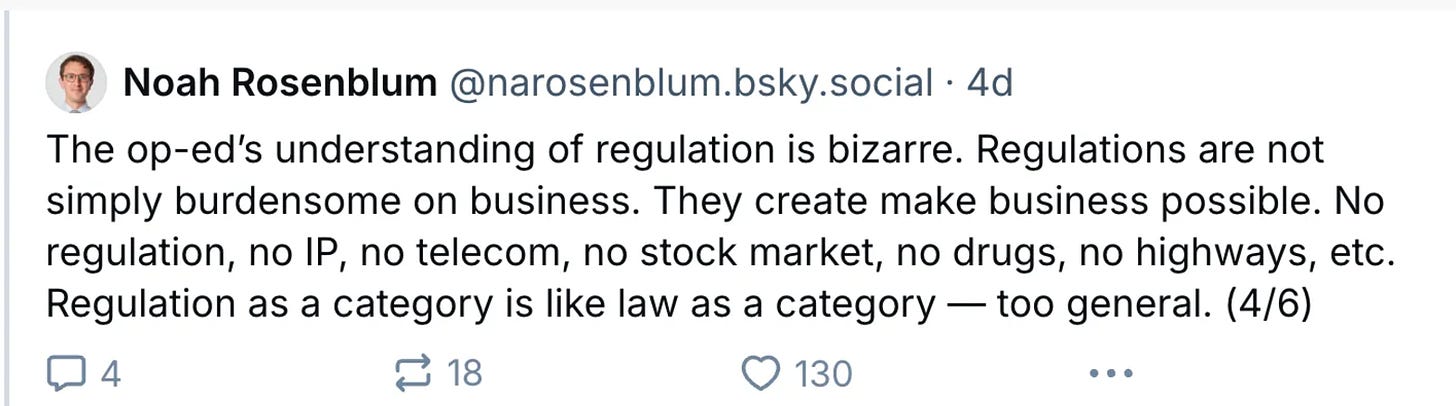

Administrative law scholar Noah Rosenblum on BlueSky that underlined the basic anti-regulatory philosophy driving Muskawamy:

Moreover, the claim that Loper Bright provides the President with power to “immediately pause” regulations is a dramatic exaggeration for a couple of reasons. Bridget Dooling, another administrative law Professor who has served in government, responded to the Muskawamy op-ed by saying:

Where to begin. Well, to achieve “drastic” reg reduction you’d have to get Congress to repeal their earlier laws requiring the agencies to write those rules. Exec branch can’t “nullify” the vast, vast, vast majority of rules on its own. And even then it would take months if not years.

Some context here is useful. Federal regulations already have to go through cost-benefit analysis to make sure that businesses are not overburdened. So it is not the case that such regulations are random. The years involved in revoking existing regulatory includes justifying why prior cost-benefit analyses were incorrect.

Dooling’s comment also reminds us that Chevron rollback focuses only on cases where there is ambiguity created by statutory guidance. Removing Chevron defense is not a license to remove regulations where there is clear statutory intent. Moreover, SCOTUS itself emphasized that Loper Bright decision did not have a retroactive effect:

By overruling Chevron, though, the Court does not call into question prior cases that relied on the Chevron framework. The holdings of those cases that specific agency actions are lawful—including the Clean Air Act holding of Chevron itself—are still subject to statutory stare decisis despite the Court’s change in interpretive methodology.

I emailed with Nicholas Bednar, an administrative law professor at the University of Minnesota who said:

the Supreme Court said that prior decisions reviewing agency interpretations of law deserved respect as a matter of statutory stare decisis. Loper Bright does not invalidate any of those regulations. It's certainly not the case that President Trump could issue an executive order to repeal any regulations. They still need to go through the standard notice-and-comment rulemaking process under the APA [Administrative Procedures Act]. That includes providing a reasoned explanation for the repeal. I am even skeptical that President Trump could issue an executive order with a list of thousands of regulations and instruct the agencies not to enforce any of them.

Richard J. Pierce, a George Washington University professor who specializes in administrative law, also cast doubt on the idea that Trump could unilaterally pause the implementation of regulations:

There is nothing in the statute that comes anywhere close to authorizing what they want to do, and no permission in the Constitution. I can’t even imagine what the argument would be beyond, ‘Gee, there are a lot of regulations and we want to get rid of them.’

Agencies have discretion on which regulations they prioritize with implementation, but cannot simply ignore the law and refuse to do their job without a risk of lawsuits.

Another basic flaw in Muskawamy’s reasoning is an assumption that regulatory rollback provides the justifications for cutting federal employees. They say:

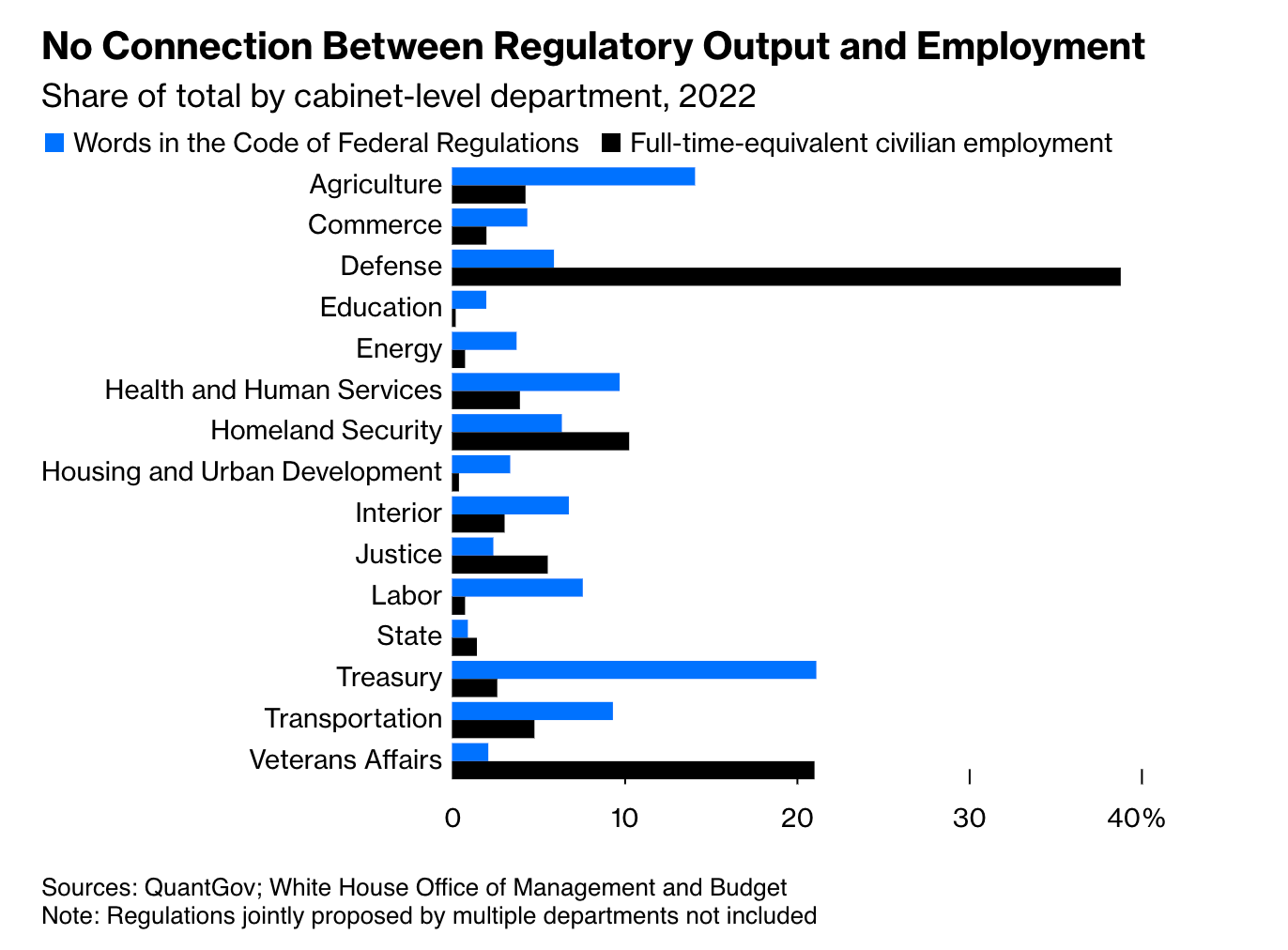

The number of federal employees to cut should be at least proportionate to the number of federal regulations that are nullified. Not only are fewer employees required to enforce fewer regulations, but the agency would produce fewer regulations once its scope of authority is properly limited.

The logic here, that there is a tight correlation between the number of regulations and number of employees, does not make sense. Some regulations are more complex than others, and some require more employees than others. And, more importantly, federal employees do a lot more than manage regulations. Justin Fox, in an excellent piece at Bloomberg Opinion, pointed out the low correlation between the regulatory footprint of different agencies, and the number of employees. The math just doesn’t match with the claims made. Also, if you cut all the regulators, who is going to do the painstaking working of cutting the regulations?

The President Cannot Refuse to Spend Money that Congress Has Ordered Him to Spend

Muskawamy also propose that the President can cut costs by not spending money that Congress has appropriated, a process known as impoundment. In their op-ed they say:

Skeptics question how much federal spending DOGE can tame through executive action alone. They point to the 1974 Impoundment Control Act, which stops the president from ceasing expenditures authorized by Congress. Mr. Trump has previously suggested this statute is unconstitutional, and we believe the current Supreme Court would likely side with him on this question.

So, a couple of factual things here. The idea that any President, but especially Donald Trump, believes something is unconstitutional is not an argument. Trump was impeached for violating the Impoundment Control Act when he withheld aid to Ukraine. So we can assume he approaches the Impoundment Control Act less with the perspective of a constitutional lawyer, and more from the perspective of a crook wanting to see the law that saw him punished wiped from the books.

The Act emerged from actions by the Nixon White House when Congress got tired of the President cutting their spending. Is the Act unconstitutional? Well, in Train v. City of New York 1975, the Supreme Court also also said that if a President cannot impound funds that Congress wants to spend. So, in short, no.

Russ Vought, the Trump head of OMB who oversaw Trump’s withholding of Ukraine aid, is an avowed fan of impoundment powers. Since he is nominated to return as OMB head, and will have direct control over spending of funds, we should take impoundment plans seriously. If nothing else, Trump et al. see no reason not to test the willingness of the Supreme Court to reverse itself and overturn Congressional intent.

Matt Glassman is a Congressional expert at Georgetown University. Here is how he characterized the plans to impose impoundment processes (emphasis in original):

if the president can choose to not spend money that Congress has been appropriated and directly demanded be spent, then the president can essentially cancel any program Congress sets up that requires funding. That’s an immense amount of power. And in my view it is a violation of the Take Care clause of the Constitution, which requires the president to faithfully execute the law. It seems totally illogical that the president could legally refuse to spend any money appropriated for the Department of Justice, simply because he decided we shouldn’t have a federal criminal code, or because Congress wouldn’t go along with his reform program…The power of the purse is the last and strongest power of Congress. The ability to appropriate will be greatly diminished, as the executive will have discretion to ignore any monies it doesn’t want spent, and the president will be able to leverage that reality to bargain for appropriations Congress does not otherwise want to provide.

You can read a longer review of the case against impoundment law here, from Professor Zachary Price, which concludes:

In sum, appropriations statutes are laws that the President must faithfully execute. When a statute mandates expenditure, as is now often the case, the President must therefore comply, unless the law infringes on some specific resource-independent power of the presidency…Renewed claims of impoundment authority, then, would not draw support from longstanding practice. Instead, they would fit within a more recent, and more troubling, pattern of executive behavior, namely, the recurrent penchant of recent Presidents for self-aggrandizement.

Muskawamy say that even without impoundment power, they can cut:

$500 billion plus in annual federal expenditures that are unauthorized by Congress or being used in ways that Congress never intended, from $535 million a year to the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and $1.5 billion for grants to international organizations to nearly $300 million to progressive groups like Planned Parenthood.

Again, I am going to rely on Matt Glassman:

this is mostly nonsense. Musk and company want to make you think that we are paying for things that nobody wants—$516 billion for programs whose authorization previously expired!—but that’s not at all how this works. Congress supports programs in two ways. First, they provide authorizations that detail the purpose of a program, the tools available, and any policy directions. These authorizations are often for a limited period of time, and often they expire before Congress has a chance (or the will) to update them. Second, they provide money for those programs, usually on an annual basis. If the authorization lapses, Congress can still provide money for the program, and that annual appropriation is evidence (legal and political) that Congress wants the program to continue.

In short, if you are the sort of person who believes that the President — or more specifically Trump — has king-like powers, you are likely to believe that Congress and previous Supreme Courts are wrong, and that the current Trump-inflected court might grant him those powers. This is where Muskawamy are right now. They have offered no compelling vision of restoring American state capacity beyond gutting regulations and eliminating employees. This might suit their businesses, but sounds less promising for the rest of us.

If there is a shade of uncertainty here about both regulatory rollbacks and impoundment power, it is not really about the law, but about how far an ever-more conservative court might move the goalposts. The point is that it would require some extraordinary shifting. Extraordinary does not mean impossible, and we have seen jaw-dropping decisions in recent years. But thats still a vast distance from the confident assertions made by Muskawamy. We should not accept their claims at face value, and we should note the real damage that will be done if others do so.

I am indebted to professors Anne Joseph O’ Connell and Don Kettl for better understanding how Federal Advisory Committees work, and for reasons to be skeptical that DOGE will follow this framework. Kettl has promised to write more on this and I will share when he does so.

Thank you so much for highlighting that DOGE is not an actual department of the federal government. It has been so frustrating to see normally competent journalists acting as if it is already a department on a par with real departments that were created & funded by acts of Congress. It feels as if we've gone into some sort of alternative history where the legal structures & safeguards fundamental to the US government has become distant mirages rather than reliable facts of everyday life.

As you point out the most this so-called department can be is an advisory body. Right now, unfortunately, it is not subject to the requirements of the Federal Advisory Committee Act. But as soon as Trump takes office, it almost certainly will be subject to FACA. (BTW, Elon & Vivek being volunteers is irrelevant to that.) Hopefully, some good government group will be taking action to do what it can to compel the Trump administration to comply with FACA. It may not be a strong tool against Trump's attacks on our government, but it is at least a tool.

FACA was passed in 1972 to assure that advice given to the federal government by advisory committees is objective and accessible to the public. In this case, it is particularly important for there to be full disclosure and lots of sunshine on the work of this so-called "department".

“They have offered no compelling vision of restoring American state capacity beyond gutting regulations and eliminating employees. This might suit their businesses, but sounds less promising for the rest of us.“ HELL yeah. as a rich plutocrat, Musk doesn’t need the protections these laws and regulations provide. The rest of us really do, though, and I think one of the things I find most confusing about voters in this election is how they couldn’t see that.