Like many political junkies, I complain about the media a lot: they miss big stories, or headlines get things wrong. With that said, there is no substitute (including blogs like mine) for deep investigative reporting. I was reminded of that this weekend, reading two blockbuster pieces from the New York Times and the Washington Post. The first, by Eric Lipton, David Fahrenthold, Aaron Krolik and Kirsten Grind, is about the baggage that Elon Musk would bring his proposed role in overseeing government efficiency in a Trump administration. The second, by Greg Jaffe, is about the anonymous whistleblower who triggered Trump’s first impeachment.

The Biggest Ever Conflict of Interest?

Trump has promised that Musk will oversee government efficiency if he wins the election. What has not been clear until now is the degree to which Musk has lobbied repeatedly for this role. On the first couple of occasions Trump demurred. But given that Musk is a massive funder of Trump’s re-election campaign, and is providing even more vital in-kind support by turning X into a Trump campaign site, Trump was hardly in a position to say no. Privately, Trump has described Musk as a “boring” weirdo, and as late as 2022 was publicly mocking him.

Musk is running four different companies, and also spends multiple hours each day on social media. So, what precisely is attracting him to government service? Why is he leveraging his access to Trump for this particular position? Well, when he posts about government, it is not exactly a well of insights about how to run public organizations. Instead, we get two types of commentary:

a) trammeling far right conspiracy theories about the deep state - most recently fueling disinformation about disaster response, or election security.

b) complaining how public agencies are limiting his companies.

Musk has two existing relationships with government.

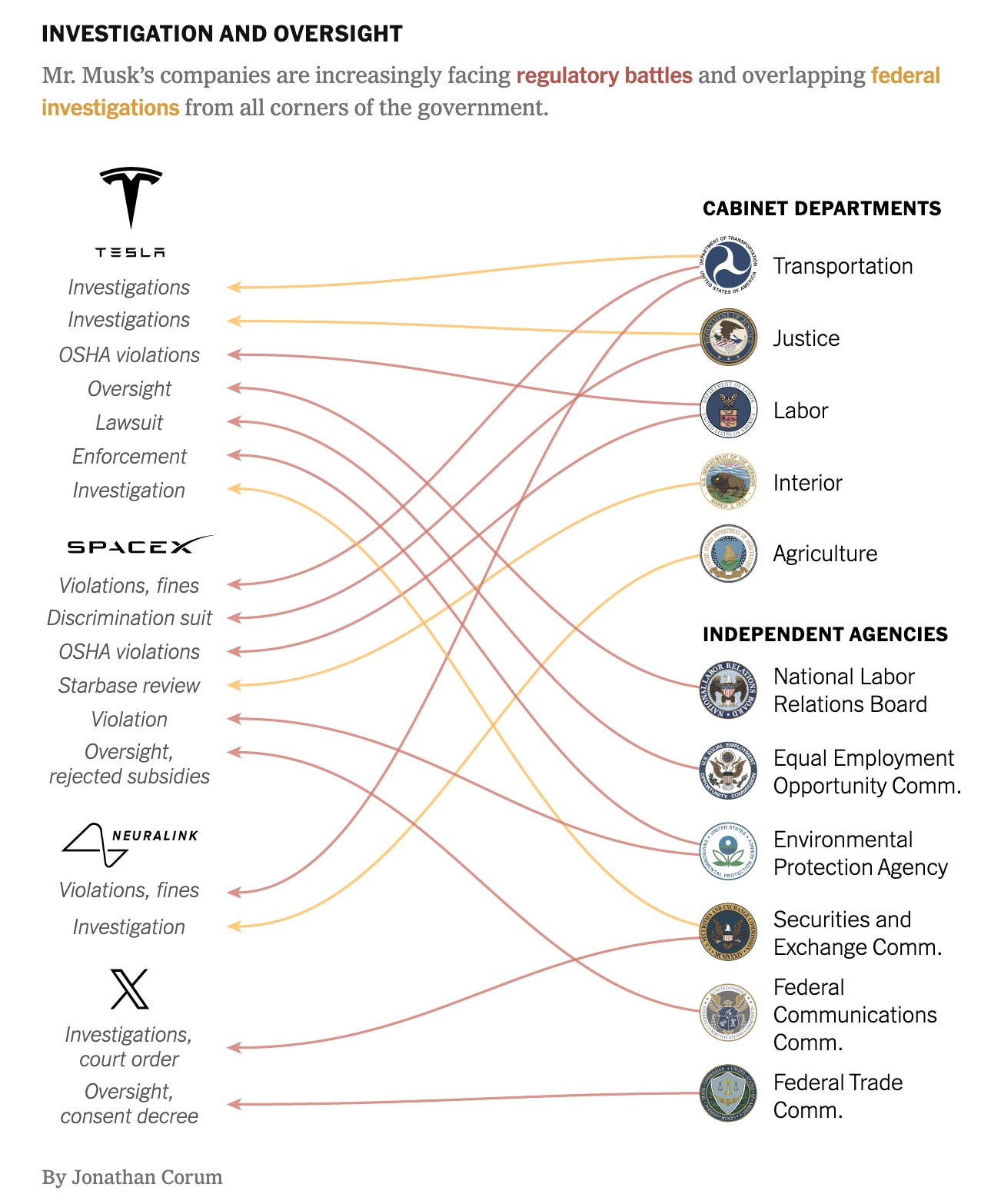

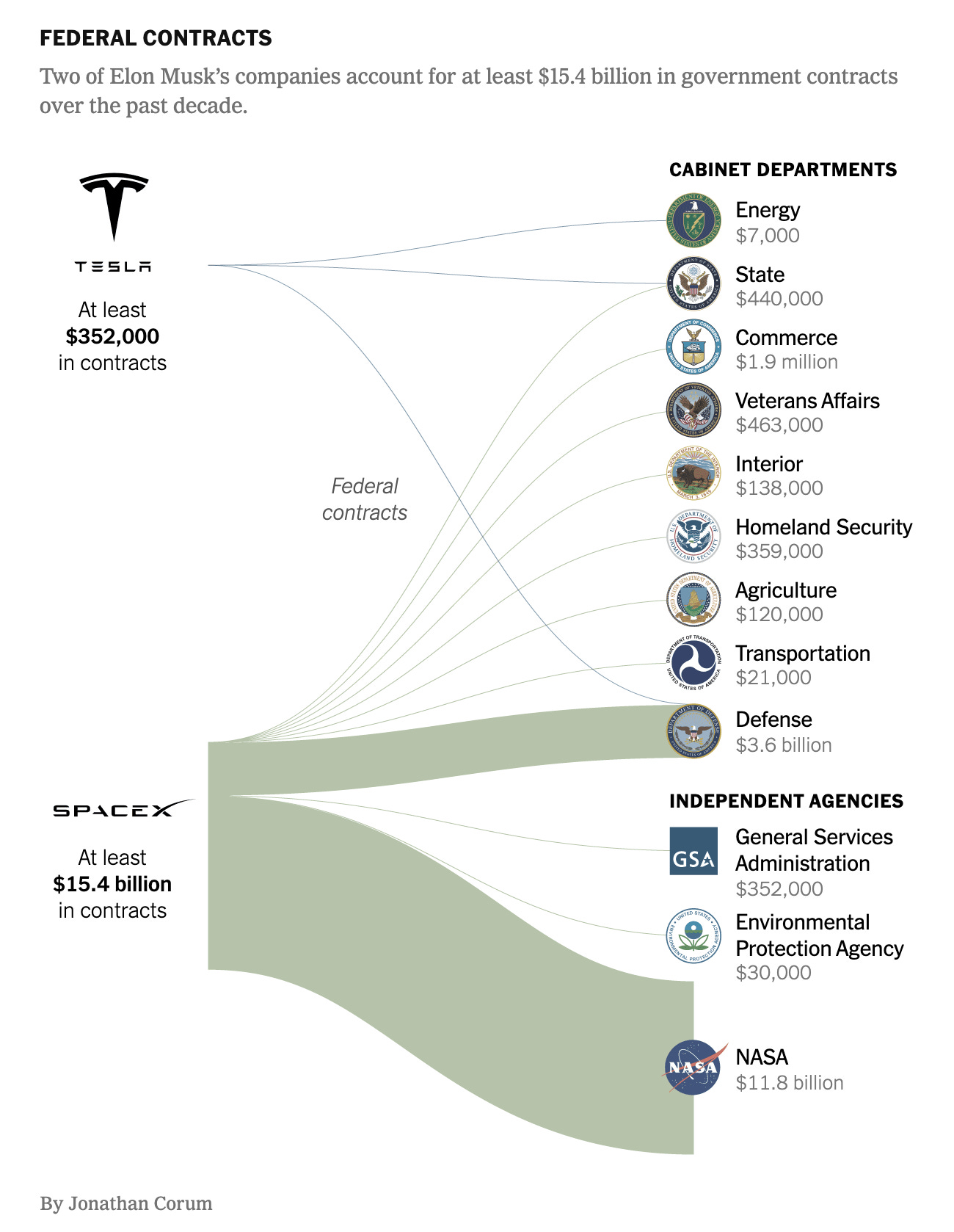

First, as a private businessman, he is subject to regulation. Musk tends to push or even ignore the law. This creates legal risks for him. For example, he has had a long-running feud with the SEC about public statements he has made about stocks and his takeover of Twitter, causing him to pay a $20 million fine and label the regulators as “bastards.” He has complained that other government regulators are limiting his Space X work, and has proposed that NASA should cancel a contract with Boeing, his main competitor in publicly-funded space travel. He is suing Federal Aviation Authority after a fine for repeated safety violations. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has multiple investigations into crashes associated with Tesla’s self-driving mode. He is fighting punishments by the National Labor Relations Board for his anti-union actions. The list goes on and on.

Second, he is also a major government contractor. Musk is already so important as a contractor — he has unique control over internet access in crisis zones, and is crucial to providing access to electric vehicles being able to refuel — that the federal government must already tread warily around him. A senior defense official discussing Musk’s threats to remove Starlink access in Ukraine said: “It wasn’t like we could hold him in breach of contract or something.” Another said: “Living in the world we live in, in which Elon runs this company and it is a private business under his control, we are living off his good graces.”

In other words, Musk is intimately involved in government, and vocal and litigious in opposing what he sees as government undermining his interests. It takes no great leap of imagination to identify that it is these business interests, rather than some abiding concern about government efficiency, that is motivating his sudden desire to be given a chance to threaten to cut specific public agencies.

There are cases of efficiency commissions in the past. The Grace Commission, under President Reagan, is one such example. Made up of businessmen, it offered a series of misleading claims that reflected their lack of understanding of government, which went nowhere. It might work out the same way with Musk. On the other hand, with Schedule F, an executive order that would give Trump the power to fire civil servants, Musk could tell Trump to remove regulators he deems to be inefficient (read: at odds with his business interests), which might suit Trump very well.

Handing Musk more power over government officials would be a disaster for regulation and accountability. Research shows that a more politicized government leads to government having less capacity and greater partisan favoritism in spending, resulting in higher costs, not greater efficiency.

I should note that not everyone agrees. According to the Times:

Maya MacGuineas, president of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, applauded the idea of an efficiency commission, and said that Mr. Musk’s experience in business could be good preparation to lead it.

It is hard to think of a more disqualifying comment from someone who is an expert on government. Charitably, maybe she added a lot of caveats that were not reported. But imagine being so committed to the Run Government Like a Business doctrine that you applaud the richest man in the world, currently engaged in an illegal voter bribery scheme in a swing state, trying to put his preferred candidate in the White House so he can cut the government agencies with which he has clear conflicts of interest. The most basic ethical standards should preclude him from serving in a position where he seeks to cut the budget, or fire senior officials, of agencies that relate to his work. But Musk and Trump’s experience boils down to this: do what you want, and bet that you can manipulate the political system to shield you from the consequences.

The Whistleblower

I am somewhat obsessed with Trump’s first impeachment, because it represents a Rorschach test for how people see the role of government. For me, it shows public servants being willing to warn Trump and his political appointees not to engage in illegal behavior (withholding aid in return for a foreign government smearing his political opponent), and then being willing to provide accountability to Congress and the public when Trump went ahead anyway. For Trump and his supporters, these were unelected bureaucrats, whose actions demonstrate the need for a Deep State purge. For example, when a Heritage Foundation official was asked on TV to give an example of how the bureaucracy stymied conservative policymaking, the only one he could offer was federal officials who raised concerns about Trump’s actions with Ukraine.

The impeachment occurred because one whistleblower assembled the evidence of Trump’s misbehavior. He did so on his own volition, drawing on his skills as a CIA analyst and his expertise about Ukraine. He has not given any detailed explanations for his actions until now.

When I teach graduate students about public management, we take some time to talk about ethics. Part of ethical behavior is following the legitimate orders of elected officials. Part of ethical behavior is responding to behavior you find unethical, or illegal. I use Albert Hirschman’s typology of exit, voice and loyalty to consider the options left to a bureaucrat. If you cannot in good conscience loyally serve an official you disagree with, it may be time to exit. Ron Sanders, who resigned from the Trump administration over Trump’s Schedule F plans, makes the case for exit. You can also stay within the administration, and engage in voice. Ethically, there is a strong case for relying on formal mechanisms of voice if they are available to you. This is what the official did, turning to a whistleblower law that allows intelligence officials to report on misbehavior.

Before using the whistleblower law, the official first sought use the organizational hierarchy. He went to the CIA’s General Counsel Office to relay his concerns:

which he hoped might be able to alert lawmakers on the Intelligence committees of the potential wrongdoing. One meeting led to a second, with even more lawyers, that finished around 8 p.m. The CIA lawyers seemed “at a loss” about what to do, the analyst said. He hoped they would notify Congress. Instead, they informed the NSC’s top lawyer that a CIA employee was raising concerns about the president’s conduct. White House officials hurriedly moved the call transcript to a server set aside for highly classified information and warned NSC officials not to talk about Trump’s call with anyone. Word of the White House’s actions got back to the analyst, who deduced that the senior officials were engaged in a coverup and sensed that there was now a target on his back.

When this approach failed, he talked to his supervisors about the option of the formal whistleblower complaint. They were not encouraging.

Lesson 1: The organizational hierarchy did not want to respond to Trump’s misbehavior until they were forced to do so. Far from the image of a deep state determined to bring Trump down, they were conflict averse, and for the whistleblower, appeared to be ready to sacrifice him.

Lesson 2: Pushing back against wrongdoing is an ethical decision framed by personal considerations. One thing I’ve heard again and again from officials placed in ethically difficult situation is the degree to which their personal circumstances matter. Many cannot afford to lose their jobs, or do not want to be put their family in danger. The whistleblower was single, and willing to deal with the consequences: “It was just me, the information and my conscience.”

Nevertheless, once the news broke, Trump tweeted about him more than 50 times, demanding that he be identified. The analyst received credible warnings that his identity would be exposed. Senator Rand Paul named the person he said was the whistleblower after much online speculation. His life was upended.

The analyst called his parents, urging them to lock their doors and contact the local police. A CIA security detail drove him to his home, handed him two black plastic garbage bags and told him he had 10 minutes to stuff them with everything he would need for the foreseeable future. They bought him a burner phone and began moving him every few days to a new hotel room.

The whistleblower would ultimately accept his supervisors urgings to work on topics other than Ukraine and Russia. He considered moving him away from the area of expertise he had spent years developing to be a demotion. He left the CIA in 2022.

Lesson 3: The process provided multiple checks against a frivolous complaint. The whistleblower complaint made multiple stops before it reached Congress. It went to an Inspector General, who had 14 days to determine if it was “urgent” and “credible” requiring Congressional notification. The Inspector General, a Trump appointee, determined that it did, while assuming (correctly) that it would cost him his job. The next step of the process was to send copies to the White House and Joseph McGuire, the Acting Director of National Intelligence, another official chosen by Trump. The Acting DNI queried the validity of the complaint that because the whistleblower was not a witness to what happened. He did not forward the report to Congress, but to the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, who suggested that what Trump had done was not an “intelligence activity” and therefore the complaint should not have been filed. Eventually, McGuire allowed the Inspector General not to forward the report, but to send letters to Congress suggesting that he was not being allowed to send an important report! Once Congress got involved, hearings followed, and the report broke.

Lesson 4: Trump has created conditions that make it much less likely that he will be held accountable again. The first impeachment motivated Trump to remake the federal government with the goal of stymieing accountability.

In a second Trump term, we will not see political appointees willing to put the rule of law before his interests. He brought John McEntee back into government to issue loyalty tests to his appointees. Trump fired the Inspector General who shared the report, and replaced McGuire with Richard Grennell, a MAGA loyalist with no national security experience. Grennell is the model for a second Trump term appointee.

Schedule F was an idea that had been bouncing around for a couple of years prior to the impeachment. Trump signed it later that year. Public officials like Alexander Vindman who provided information to the whistleblower, and Congress, would now simply be fired. If Trump and Schedule F returns, officials who want to keep their job will turn a blind idea to illegal behavior by their political masters.

Trump has perfected the art of intimidation of public officials, to the point where conditions of terror are becoming normal for anyone deemed a threat to Trump. How many public servants will raise complaints, even anonymously, when they know they will face enormous personal and career costs?

Trump will install lawyers across government, and take more direct control of the DOJ, to ensure a legal buffer that will quash complaints against him.

Even before these changes, the analyst paid a high price for his willingness to share information about wrongdoing. Today, he remains convinced that “the public needed to know” but is unsure if it made any real difference.

Reading the two cases side by side, it is hard not to compare the contrasting vision of public service offered by Musk and the impeachment whistleblower. One sees government as an impediment to his business interests, and public service as an opportunity to advance those interests. The other sacrificed his career and personal safety because of an idealistic belief that accountability mattered. It is very clear which vision of government will become more central if Trump returns to office.

Ethics is a top-down notion within organizations. Since Trump is amoral, completely unconcerned about whether an action is right or wrong, he set the tone while in office, within his business organization and within his campaign. Trump knows right from wrong, he simply doesn't care about the ethical ramifications of his actions; he just wants what he wants. The problem is that all ethical systems ultimately rely on the character of people. Voters need to understand how crucial it is not to vote for unethical candidates who hurt the system and everyone in it and affected by it. This is also why most systems have checks and balances.

What would stop a Harris administration seizing Starlink and SpaceX on national security grounds, and booting Musk out? Serious question.