Biden's new student loan plan is a BFD

Automatic renewals can vastly expand the reach of more generous income-driven repayment plans

When you are living through a policy moment it is sometimes clear what is, as President Biden once put it, “a big fucking deal.” And sometimes it is not. For the past couple of years almost all of the headlines and energy around student loan reduction centered on Biden’s plan to forgive $10,000 to $20,000 worth of loans, a plan that the Supreme Court shot down.

But what if another part of the plan, income-driven repayment (IDR), ends up being the BFD?

Like lots of people, I was interested in the student loan forgiveness plan, with a particular focus on how administrative burdens might play out.1 At the time, I remember chatting with others about how IDR had the bigger longer term potential, but policy scholars, like everyone else, tend to focus on the short-term rather than long-run change. With IDR, I am, again, interested in the role of administrative burdens, in particular the use of automatic enrollment and renewals. I’ll explain why that matters so much below.

Biden has already done a lot on student loan reduction

Before we get into the details of IDR, its worth recounting what the Biden administration has already done. The focus on the broad student loan forgiveness program has obscured other actions that Biden administration has taken that are expected to lead to more than $116 billion in student loan reduction for 3.4 million people:

$39 billion for 804,000 borrowers by fixing errors with IDR plans;

$45 billion for 653,800 public servants through improvements to Public Service Loan Forgiveness Programs;

$10.5 billion for 491,000 borrowers who have a total and permanent disability; and

$22 billion for nearly 1.3 million borrowers who were cheated by their schools, saw their schools precipitously close, or are covered by related court settlements.

Some of these were existing programs or initiatives that started before Biden, but it is fair to say that no prior administration has worked as aggressively to push student loan reductions. The central theme of these initiatives has been to reduce burdens in existing programs to make them more accessible and functional. The new initiative follows this pattern. IDR was already a tool in the toolbox, but not one used to the degree it could be. If the Biden administration succeeds, the new IDR will be transformative both in terms of its generosity and reach.

What the SAVE plan would do

The Biden administration unveiled SAVE (Saving on a Valuable Education) earlier this year, but more details became clear this week as it opened for enrollment. The Biden administration will invite 30 million borrowers to benefit from the initiative.

SAVE has a number of features. It limits loan balances from growing if borrowers fail to make interest payment. If they keep making payments, their balance will not grow due to unpaid interest growth.

But the heart of SAVE is expanding IDR, which ties repayment to a percentage of income and number of dependents. The SAVE plan improves these terms of IDR, limiting payments on to just 5 percent of discretionary income for undergraduate loans and 10 percent for graduate loans. SAVE also expands the dollar amount of income protected from repayment. This is expected to save the average borrower about $1,000 per year, but the effects are greater for borrowers with less money to spare. The New York Times notes that “a single person who makes less than $32,805 a year would make $0 monthly payments. The same goes for someone in a household of four with income below $67,500.” Low balance borrowers will see their loans forgiven after 12 years rather than 20.

I asked Professor Dominique Baker, an expert on educational access if SAVE has the potential to to eclipse student loan forgiveness.

I think it will definitely be as big of a deal. One of the “big” pieces about SAVE is that it is reshaping how student loan repayment happens. That, paired with one-time debt cancellation and reforms to the price of college is how we both fix the harms of the past and change the system so that it doesn’t happen again. I think of it as part of a larger scale project to reorient higher education back to being a public good, with public institutions primarily funded by public dollars (a fun mix of federal, state, and local monies).

IDR deals with some of the criticism that student loan forgiveness faced.

Loan should be repaid!: IDR centers on repayment, not forgiveness, but making the terms of repayment more generous to borrowers.

Generational equity: Loan forgiveness was designed to help today’s borrowers, not those from a previous generation, or future borrowers who end up in the same hole. IDR will be available to both current and future borrowers.

Loan forgiveness is both too expensive and not progressive enough. Research by Sylvain Catherine and Constantine Yannelis suggests that automatic enrollment into IDR serves as the least expensive and most progressive policy option they considered. According to the New York Times: “the lowest earners may see their payments fall 83 percent, while the highest earners would receive only a 5 percent reduction.”

IDR is a great opportunity for borrowers, but it is beset by administrative burdens…

Even before SAVE, IDR was already a great deal for most borrowers. But about half of those with low incomes and high student loan debt don’t enroll. Why hasn’t it been more broadly embraced?

The short answer is that its a classic case of administrative burdens, where learning, compliance and psychological costs are enough to keep people from using a program they would benefit from.

Baker explains:

In the US, you had to know about IDR, sign up for IDR (it’s not the default program), certify your salary every year, track your payments yourself because servicers (the contractors the government uses to administer student loan repayments) don’t, and more. That’s a lot of hoops for borrowers to jump through to ensure they can have their debt cancelled…Up until these more recent changes, the US made it incredibly challenging for borrowers to learn about the IDR program, sign up initially for it, to remain enrolled, and to know when you have reached cancellation. These factors all combined to make it incredibly unlikely that anyone would get their debt cancelled (which is exactly what happened). So in fact, it’s rather astounding that folks signed up for the program given all these hurdles.

Elsewhere, Bryce McKibben, a former Senate staffer who advocates for college affordability wrote that:

the documentation requirements for income-driven repayment have created significant hurdles and disparities for the borrowers most in need of relief from their debt.

Adam Goldstein and colleagues provide a detailed account of the burdens in IDR programs, which stem in no small part from the reliance on a network of private servicers, concluding that

borrowers with lower socioeconomic status (SES) are disproportionately excluded from the very federal programs intended to help borrowers manage the costs and risks of debt-financed higher education.

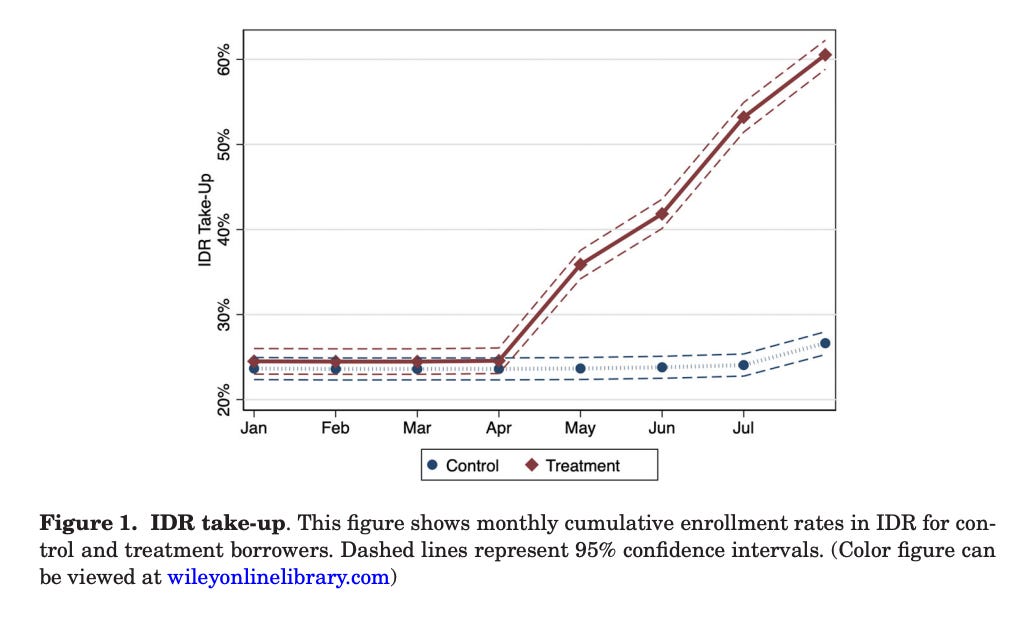

To give a sense of the scale of the barriers in IDR programs, I’m going to share one of my favorite burden reduction graphs:

This comes from an experiment where Holger Mueller and Constantine Yannelis compared take-up in IDR programs from the status quo (where take-up is about one in four of eligible borrowers, surprisingly low) to an experiment where eligible borrowers were emailed pre-filled forms that required them to only sign and return the application to participate. Using pre-filled forms to reduce burdens increased take-up to over 60 percent. The experiment demonstrates the tremendous room that reducing administrative burdens can do to expand IDR.

…which is why automatic renewals will matter enormously

A lot of the attention to administrative burden reduction efforts goes toward improving application processes, as with the experiment above. After all, you can’t help people if they don’t engage with the program in the first place. The Biden administration plans to automatically enroll anyone already in an existing IDR (REPAYE) plan into the SAVE plan. This will move lots of people onto a better path.

But once you people on a program, there is no guarantee that they stay on. Programs with frequent and complex renewal processes lose lots of eligible beneficiaries. We are witnessing exactly this right now for Medicaid with the end of the Public Health Emergency, where millions of eligible people are struggling with renewal processes.

A powerful way to fix this problem is to automate not just enrollment but also the renewal process in cases where government has the data to verify that the person remains eligible. In the case of student loans, the IRS has this data. But we have made it very difficult to share IRS data with other agencies. It literally requires an act of Congress. In 2019, the passage of the FUTURE Act enabled such data sharing for the purposes of educational access.

The FUTURE Act still requires borrowers to agree to allow the IRS to share this data. But once they do, the Biden administration can use this consent each year to verify that the participant remains eligible. In other words, the government will do its best to renew borrowers in the program rather than asking borrowers to do it themselves, and losing them in the process.

This sounds like a small change, but those familiar with both IDR and the effect of administrative burdens see it differently. On Bluesky, Professor Sue Dynarski, an economist at Harvard who has done a great deal to examine how to reduce barriers to higher education, posted that:

Baker explains that automatic renewal “removes a substantial burden that was placed on borrowers…I think this is an exceptional step forward.”

If the Biden administration can get people on the new IDR, they have a tool to keep those people in place, benefiting from the improvements in place. This still requires persuading current non-participants to sign up, and to provide permission to share their IRS data, which may be no small challenge. But for lower-income borrowers, this means that IDR becomes not just a much better financial deal, but also that the benefits of IDR are not wrapped up in ongoing burdens that they have to renegotiate every year.

In short, Biden is putting more money on the table, and making it a lot easier for borrowers to claim it.

Administrative capacity is a potential stumbling block

We can read the Future Act as a framework to reduce administrative burdens and make government work better. The Biden administration very much wants to exploit it. But that framework is not self-executing. It needs competent administration. And this creates a real potential stumbling block that could undermine student loan reduction.

The IRS is a good example of what can happen when a government agency has a clear idea of how to improve services, and gets the resources to do so. With new funding, the IRS has almost eliminated a massive paper return backlog, and cut phone wait times from 29 minutes to 4 minutes, and has started to invest in new digital tools like return-free filing.

If the Biden administration wants to see its ambitious goals for student loan reduction to come to pass it will have to solve a capacity problem. Congress has kept funding flat for the Office of Federal Student Aid that will implement these changes. Accounting for inflation, this effectively amounts to a cut in resources available. Professor Baker notes that: “It’s a challenging policy environment to get meaningful policy passed in Congress, but it’s an even more challenging environment to ensure that the federal government is adequately funded to implement those policies.”

Since IDR removes many of the objections that the GOP had about student loan forgiveness, maybe Republicans will return to the more bipartisan approach for funding that once characterized education spending. If not, the Biden administration will be in the difficult situation where it has an ambitious plan to make public services more accessible but is stymied by a lack of government capacity. This matters because SAVE will be complex to implement, partly because of the complex nature of IDR programs that Goldstein et al. point to:

IDR is intended to personalize debt payment to borrowers’ individual situations, and to do so dynamically in response to the reality that many Americans experience fluctuations in income. However, the complexity and frequent documentation that accompanies this adaptiveness—along with the multiplicity of program variations that create further choice burdens—together create confusion for borrowers and street-level bureaucrats alike.

Ultimately, if the SAVE plan is to work it will be over the long haul, rather than on one triumphant day when people see their loans disappear. It will have built on decades of incremental coordination between agencies, and dependent on administrative capacity and the management of private contractors. This is the business of government, slow and often unflashy, even if the long run effects are transformative.

I wrote first about how enrollment process could be an administrative nightmare, and then when it was unveiled, about how it was actually a triumph of simple, user-centered design. Happy to be proven wrong!