Biden deserves more credit on student loan reduction

How the politics of credit and blame intersects with the student debt crisis

At the State of the Union, President Biden boasted: “I fixed student loan programs to reduce the burden of student debt for nearly four million Americans including nurses firefighters and others in public service.”

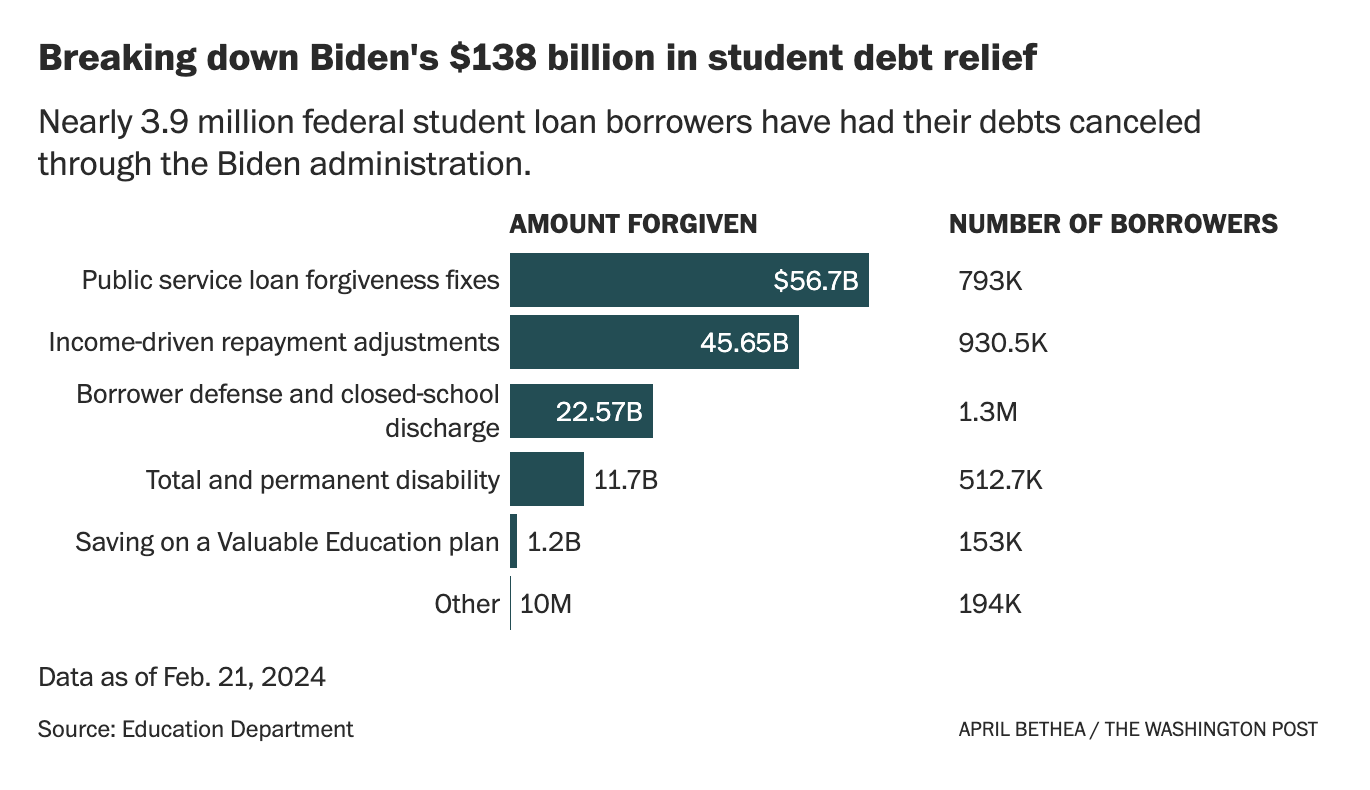

Will Biden get political credit for this? Republicans oppose Biden’s loan reduction efforts, and many on the left think he has not done enough. So there is a limited audience willing to sing Biden’s praises in this area. This is a shame, because there are real achievements that deserve credit. Biden has now erased $144 billion in student loan debt.

One hopeful sign is that John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight did an in-depth breakdown into the student debt crisis, and did, in fact, give a shout-out to Biden’s efforts to address the problem.

We might think about Biden’s progress on student loan reduction as a weird hero’s journey through the maze of American policymaking and implementation. He started with a bold goal of mass student loan forgiveness for all borrowers. This was thwarted by the Supreme Court. So he instead takes on a more laborious path, finding smaller tools and incremental fixes that allows him to hack his way through broken programs, and along the way may have discovered some long-term solutions.

The end of the story is unclear. As I’ve noted before Biden’s SAVE Income-Driven Repayment plan has enormous potential. The SAVE plan helps not just past borrowers, but also future borrowers. So it’s not a one-off solution. SAVE’s potential, and other initiatives Biden has started, could be reversed by an administration opposed to student loan reduction. The Heritage Foundation’s Mandate for Leadership, which represents the closest thing we have to a Republican Party platform, opposes the SAVE program because it is:

extremely generous to borrowers, requiring only nominal payments from most students. It would turn every policy lever to the most generous setting on record (e.g., lowering the percentage of income owed from 10 percent to 25 percent under existing plans to 5 percent, lowering the number of years of payment required from 20 or 25 years to 10 years, and increasing income exemption from 150 percent to 225 percent of the poverty line)…This plan essentially converts these student loans into delayed grant programs.

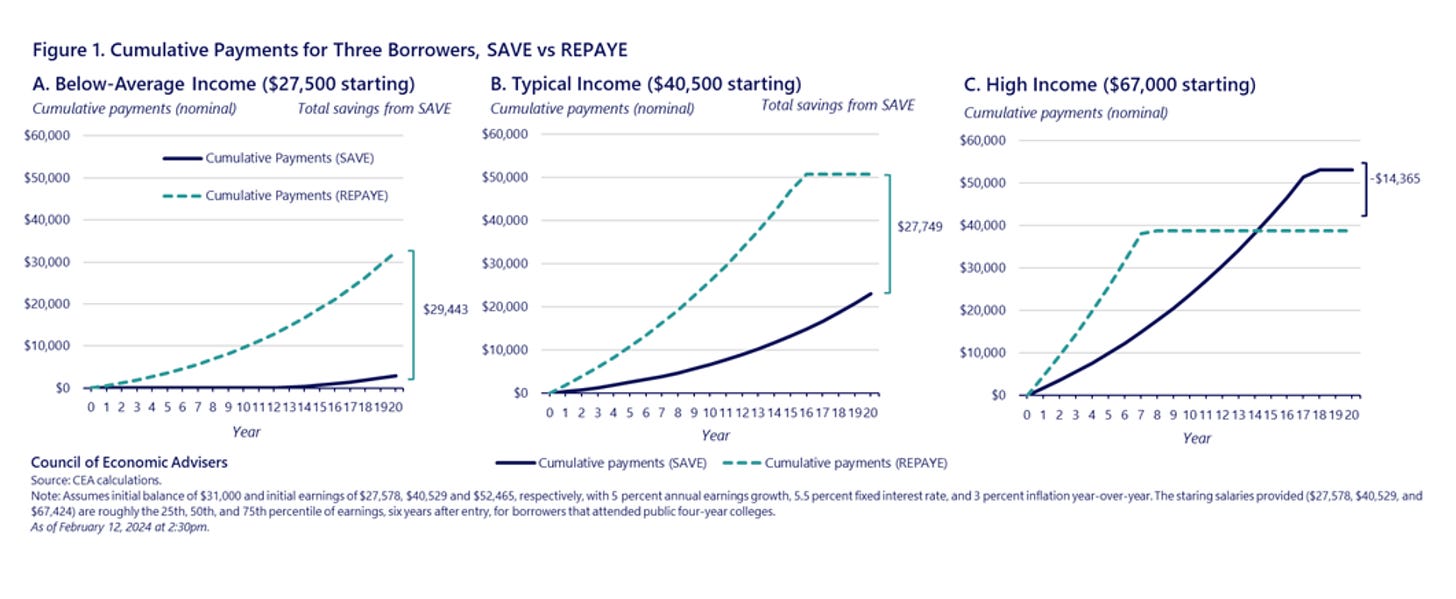

SAVE also targets the most needy. Biden’s original loan forgiveness program targeted people with $10,000-$20,000 in debt, which accounts for more than half of borrowers. Under SAVE, those who borrowed $12,000 or less see their debts forgiven after 10 years of payments. Simulations released by the White House show how much better SAVE is for lower-income borrowers than existing IDR programs.

SAVE has led to $1.2 billion in savings already, and will grow significantly if the program survives the next election. Ellie Quinlan Houghtaling wrote about the surprising inattention to SAVE relative to the scale of its benefits:

Under other repayment plans, the average borrower ends up paying more than the original amount they borrowed because interest accumulates. But the average undergraduate borrower who uses SAVE will repay only 60 cents on every dollar they borrowed. For low-income borrowers, the entire balance will be forgiven. For millions of Americans, SAVE will be debt cancellation in the form of debt repayment. In other words, the large-scale debt relief activists have spent years fighting for is finally here—it just didn’t arrive in the packaging anyone expected. And no one’s talking about it.

Part of the reason that SAVE has not drawn more attention is because it is starting small, and historically IDR programs have themselves been beset with problems. But if run well (and there is reason to believe it will be) they allow Biden to say that he is not just helping today’s students and past borrowers, but also the parents of school kids who hope to go to college. It could be a big inter-generational benefit, but has been treated as a side note in the debates on loan reduction.

Fixing Broken Programs

Before SAVE, much of the Department of Education’s efforts were directed to making Kafkaeqsue processes feel less arbitrary and more humane, while also fixing broken programs. A new report from the Better Government Lab at Georgetown University documents just how burdensome these processes were, and the degree of effort required to make them work. Dig into the details of some of these programs, and the combination of learning, compliance and psychological costs demanded of borrowers who were trying to do the right thing is infuriating. In some cases, the Department of Education used waivers or one-time fixes to manage around poorly-designed policies, or errors made by loan servicers that effectively and unfairly denied borrowers loan relief to which they were legally entitled. Fixes included counting prior payments that would not otherwise count toward loan forgiveness. Department of Education changes also made it easier for clients to learn about whether their employee qualified through an online system, and moving to digital applications that did not require wet signatures. When it had greater authority, it moved to automatically discharge loans, such as for those with total and permanent disabilities.

The bulk of student loan reduction comes from fixing the Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program, which Biden referenced in his state of the union address. The program offers loan forgiveness for people, like teachers, who go into the public service, but had gained a reputation for dysfunctional. Borrowers in many cases believed they had done what they were supposed to in order to qualify for the program, but then were told that they did not, or allowing late payments or payments made during forbearance. The program has made remarkable progress under Biden. The current number of people receiving debt forgiveness stands at 871,000 for a total of $62.5 billion. By contrast, just 7,000 people had received forgiveness through the program before Biden took office.

Progress Depends on Political Commitment and Capacity

One point the Better Government Lab report makes is that student loan reduction as a policy project has become polarized. Democrats want to do more, and Republicans want to do less. There are some exceptions. Groups perceived as politically deserving, such as veterans or those with disabilities have benefited from bipartisan support and saw some progress under the Trump administration. But mass loan reduction is much more divisive. This makes it harder to imagine a Congressional solution to addressing student loans that requires 60 Senate votes. This polarization extends beyond policy to implementation. A Trump administration will not only not seek to extend loan forgiveness programs, and may withdraw some, but it will also be happy to return to dysfunctionality again. We know this, because that is what they did while in power. As the Better Government Lab report notes:

Students were unsure of their application status and faced an agency led by political appointees, particularly then Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, who refused to allow the program to function. In fact, according to a lawsuit filed at the time, Sweet v. DeVos, the Department was intentionally, and illegally, preventing approximately 170,000 applications from being processed.

James Kvaal, the Under Secretary at the Education Department emphasized the centrality of leadership commitment to either encouraging or fighting such problems:

One important thing that has to come from the top is prioritization…and simplicity is not always the highest priority for everyone. In the aggregate nobody is trying to make the judgment of whether we are forcing people to wade through too many questions that are irrelevant for benefit delivery. That is the kind of thing leadership needs to do; to make sure that simplicity is a goal.

The report also points out how fixing existing programs, and processes that involve third party loan servicers, is complex, and requires capacity on the part of Federal Student Aid (FSA), the part of the Department of Education that deals with these issues.

Three significant limitations that have been most challenging for the Department of Education to overcome include: (1) The Department’s reliance on private loan servicers, and corresponding inability to impel these servicers to comply with its goals regarding the quality of the customer service that student loan borrowers receive; (2) Governmental barriers to cross-agency collaboration, particularly regarding limited data-sharing allowances that often result in Americans submitting the same information to multiple different agencies; and (3) Limitations in the agency’s leadership’s ability to handle the many complex, and growing, student debt relief programs.

Kvaal pointed to the capacity issues for FSA:

At an organization like FSA the leadership can only handle so many priorities, can only manage so many projects at a time, their deputies can only manage so many projects at a time, so you have to figure out what is most important and prioritize.

The Financial Hardship Strategy

So, we basically have the SAVE plan (massive long term potential, under-appreciated now), and fixing existing loan forgiveness programs (smaller but immediate impact). There is another gambit the Biden administration is pursuing, which is debt forgiveness based on financial hardship.

Debt forgiveness advocates are angry Biden did not take this strategy earlier, rather than relying on the HEROES Act for his prior student loan forgiveness program. But HEROES allowed quicker executive action. By contrast, the Higher Education Act, which can be used for financial hardship, requires a negotiated rulemaking process that is slow and onerous. The Education Department has drafted a proposal to cancel debt for those experiencing financial hardship. What constitutes hardship will be subject to disagreement, with loan forgiveness advocates pushing for more while the Department of Education has proposed a cap of $10,000. While legal experts say the plan has a firmer legal underpinning than the student loan forgiveness plan, SCOTUS in that case invalidated the program relying on major questions doctrine, so the more ambitious the scale of loan forgiveness, the more likely it is they will do so again.

Problems with FAFSA

At the same time, the program that allows student access to financial aid, FAFSA, is struggling. With the FAFSA Simplification Act of 2019, Congress directed the Department of Education to make the program simpler and more accessible, a laudable bipartisan goal. Delays in rollout of the new FAFSA, contractor problems, calculation errors, and a glitchy product has, in turn, created to delays in students being able to access financial aid.

Jen Pahlka, author of Recoding America, points to FAFSA’s problems as endemic of a broader state capacity problem. For example, she noted out that the contractor building the new system (because American governments do not build their own digital systems) is one that worked on the disastrous Affordable Care Act website.

We don’t know enough about what happened to know what exactly went wrong, and this deserves a separate analysis. But thinking about it in the context of student loans forgiveness, there are some plausible lessons.

Separation between policy and implementation: FSA staff input about the challenges of the new FAFSA system went unheeded. As complications arose, such as working with the IRS to share income data or building a new system rather than updating a decades old COBOL-based system, Congress did little to respond beyond extending deadlines by a year.

FSA is doing more without more resources: In addition to student loan relief, FSA was also involved in distribution COVID relief funds, modernizing its student loan servicing systems, and restarting loan payments after the pandemic. But Republicans have pushed against budget increases, and even called for cuts because of their opposition to Biden’s student loan reduction efforts. I reached out to Edward Conroy, an education expert at the New America Foundation, who said: “It remains a massive problem that ED is managing a vast array of tasks and projects, including bringing borrowers back into repayment, which no administration has ever had to do, and is doing it with very limited resources. You can’t ask more and more of an agency, keep funding flat, and then be surprised when some thing finally breaks. That is going to need to be fixed or it’s likely we will see continued problems.” Representative Virginia Foxx, the senior Republican on the education committee, has sent a letter to the Education Secretary Miguel Cardona accusing the Department of focusing “its time and resources on transferring student debt to taxpayers rather than on faithfully implementing the laws enacted by Congress.” There is some validity to the point that public organization taking on new tasks have less capacity to manage existing tasks. Resources are not just just money, but also time and attention, and as leadership focused on new tasks like student loan reduction, it may have diverted from FAFSA. On the other hand, Foxx and other Republicans have opposed any new fundings to enable the agency to take on new responsibilities.

Internal management problems: Prior to the current Chief Operating Officer, FSA had high turnover in this position, and in others positions, such as those overseeing human resources. While in theory the organization is a semi-autonomous Performance Based Organization, intended to be insulated from politics, that is not how it operates.

The FAFSA process will get better. Lots of families interact with FAFSA, and so the Biden administration has a strong incentive to make it functional. A good general rule of thumb is that governments are bad at novel tasks, but then get better as those tasks become routine. Ideally, problems are discovered during piloting of new systems rather than through systemwide rollouts, as we are seeing now. The Affordable Act website is a good example of a system that failed badly, and very publicly, and then got a lot better. The New York Times report shows senior leadership pushing aggressively to fix problems, and staff voluntarily working overtime to resolve them. So I’m optimistic that the administration can learn lessons to fix problems for next year, but this really does depend on an administration wanting to do so, and fixing the FSA capacity issues.

The Paradoxes of Public Service Improvement

This leaves some unresolved questions. One is whether FAFSA fallout will generate more political blame than the student loan success generates political credit? Research on negativity bias, which emphasizes that we pay more attention to negative rather than positive outcomes, suggests so. This creates a governance problem, where the gains of innovation in government services might generate clear benefits for the public, but the political risks of innovation generate losses for politicians.

Another behavioral explanation for how the public will, or will not, give political credit is people’s reference points, i.e., the basis of their expectations. If your reference point was mass loan forgiveness, only to see those hopes dashed, it is understandable that the incremental approach feels insufficient, even if the long term benefits are great. Counseling patience and understanding will not be greeted warmly. It is also the case that the progress made in this policy area reflects the ability of loan forgiveness advocates to successfully make their case, at least within the Democratic Party. By aggressively pushing the issue, they have pushed the Biden administration despite the fact that loan forgiveness may not be a big vote winner for the general public.

If your reference point is the past, or the immediate future, Biden has done a lot. He has cancelled more student debt than all other Presidents combined and created a better long-term equilibrium for borrowers. A Trump administration is likely to roll back many of the loan forgiveness programs, and return to a policy of deliberate neglect and dysfunction for those that stay on the books. If trying to fix big problems fails to generate a political return, we can expect both that these such efforts to be stalled and reversed, and a setting aside of the kind of good government tinkering that Biden engaged in to get there.

These questions of political credit are not just partisan issues. In a political system where there was a) broad agreement on how to fund higher education and address more than $1.7 trillion(!) in student debt and b) the need for sufficient administrative capacity to do this well, we would not be having this debate. But thats not where we are, and as it seems to be the case for many aspects of the American policy landscape, those who want to take on real problems are operating with one hand tied behind their back, and then blamed for not doing enough.

Great discussion of the student loan situation, and including the John Oliver video was very helpful. I do think that in areas where the government has to outsource, such as to student loan servicing companies, it should implement the same sort of system used in corporate America - customer service ratings. Every borrower who contacts the company should be asked to rate the interaction and every borrower should be sent an electronic annual questionnaire about the company. Companies with high customer satisfaction can receive incentives while those with low satisfaction will not qualify for incentives - a carrot and stick approach. This is something that is done with A.I. and it's fairly easy to implement. I feel certain that borrowers would love to comment.

Quite the contrast to the cruelty of the Trump/DeVos years....