Ballots and Burdens

Why states are moving to automatic voter registration, and how it could be improved

Heretofore we have assumed that voting is a costless act, but this assumption is self-contradictory because every act takes time. In fact, time is the principal cost of voting: time to register, to discover what parties are running, to deliberate, to go to the polls, and to mark the ballot. Since time is a scarce resource, voting is inherently costly. - Anthony Downs

While many new election laws might not have easily detectable aggregate effects on turnout or election security, they may still impose or reduce burdens on citizens. In a new paper for the Institute for Responsive Government, who examine specific tactics to broaden participation, I argue that policymakers, the media, judges and the rest of us should be using burdens as the central way to evaluate voting laws. Moreover, we should have a bias towards reducing those burdens to eliminate barriers to basic political rights.

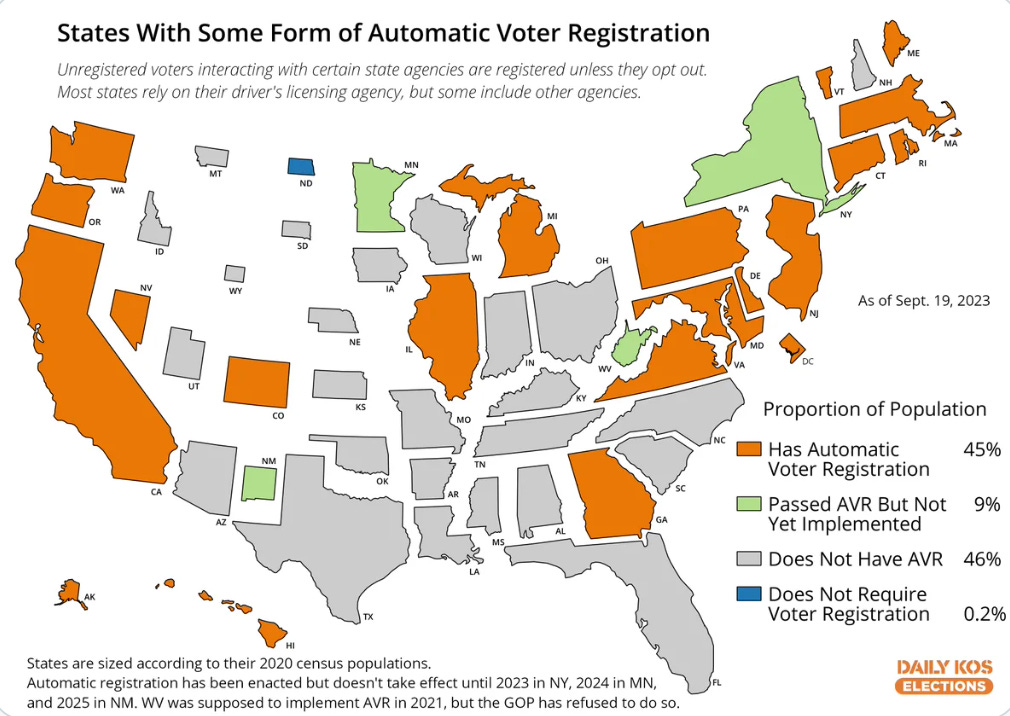

Automatic voter registration is the type of policy you should embrace if you care about minimizing burdens, since registrations impose a largely pointless barrier to voting. Oregon pioneered AVR in 2015, and now almost half of states and Washington, DC, have embraced some form of automatic voter registration at DMV offices.

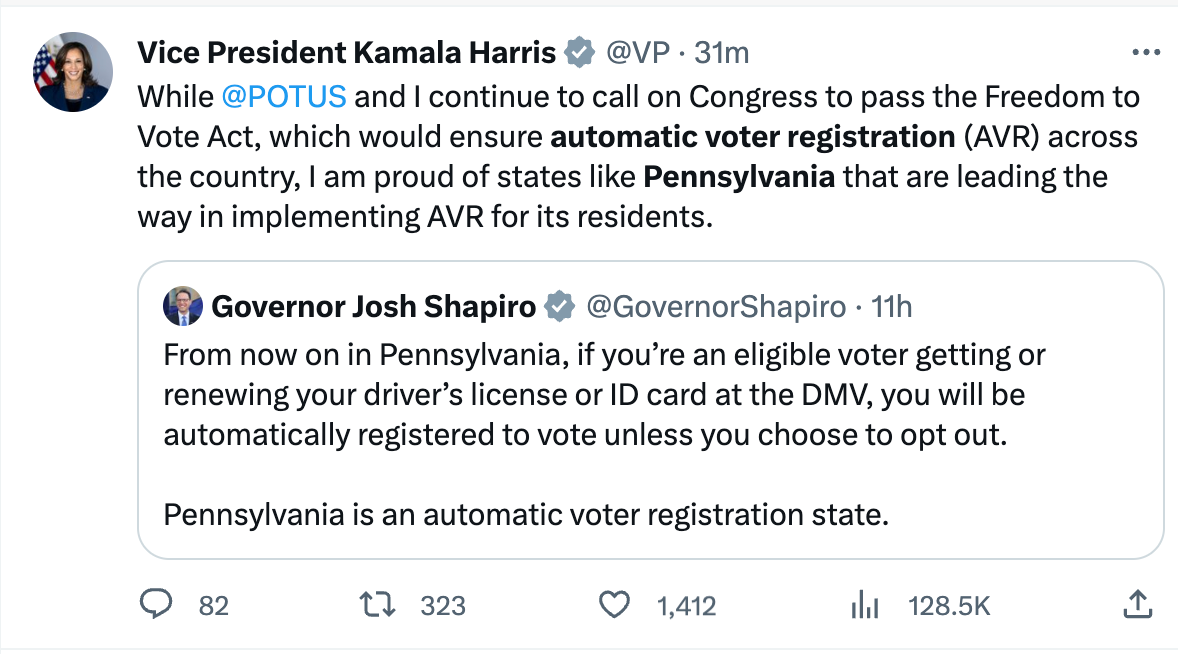

Pennsylvania is the most recent adopter under Governor Josh Shapiro. Since we live in a time when making it easy to vote has become a partisan issue, AVR is no exception. So on the one hand, Democrats cheered the change…:

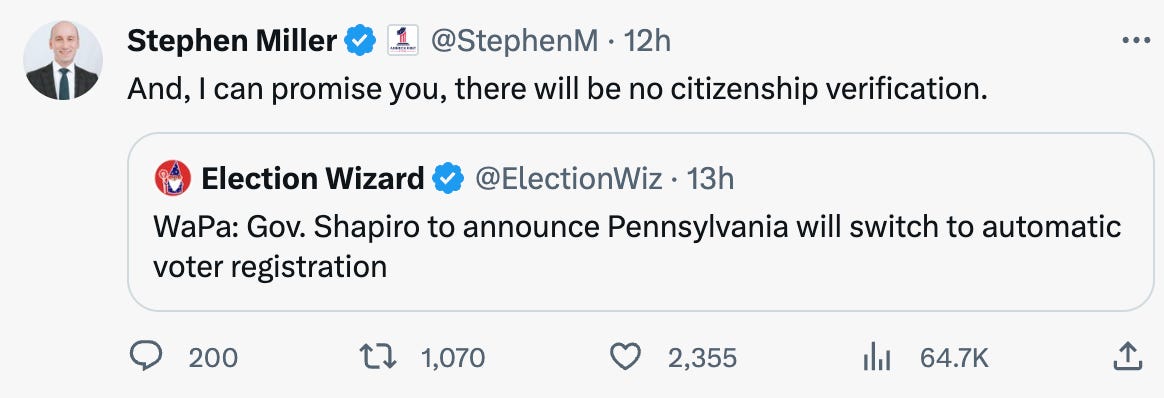

…while prominent white nationalist and former Trump official Stephen Miller claimed there would be no check on non-citizens voting.

This is false. For one thing, Pennsylvania DMV collects citizenship information to minimize risks of non-citizens registering. More broadly, AVR has the same protections against non-citizens registering as does other forms of voter registration. Maybe Miller would like to add new citizenship documentation requirements to all forms of registration, but this is illegal.1

Why even quote Miller, you ask? Astonishingly, both The Washington Post:

and The New York Times:

…and other outlets repeated Miller’s claim without a fact check. So someone has to! (Reporters: you do not have to uncritically use someone with a documented track record as a serial liar on the topic you are writing about! If you do, at least verify their claim. If you don’t know the policy domain, talk to an expert that cares about their reputation for accuracy).

But Miller and others shouting “fraud” fit comfortably with a shameful tradition. The adoption of voter registration processes relied on election integrity arguments as a rationale to exclude poorer, less educated, and later, Black citizens.

Today, the opponents of AVR believe that it will hurt Republicans, not because of fraud, but because they believe that they are less likely to win if more people vote. And so they search for arguments to justify maintaining election burdens. Back in 2022, Shapiro’s opponent for Governor promised to force everyone to re-register to vote: “We’re going to reset, in fact — registration, you’re going to have to re-register. We’re going to start all over again.” Guess what? AVR performs the same basic function of purging the voting rolls — ensuring the rolls reflect current voters — while minimizing hassles on citizens and ensuring that eligible voters do not lose the chance to vote. AVR therefore improves election integrity. But as is the case with Republicans abandoning the Election Registration Information Center, the goal is not so much minimizing election fraud as much as it is to maximize burdens.

While the basic logic of AVR is clear — the costs of registration are reduced by taking advantage of administrative data, most likely at the DMV — the details of implementation matter. What AVR means can vary from one setting to another, and the effects on registration differs depending on how the AVR system is implemented, and the degree to which it reduces versus eliminates burdens. So prepare for a deep dive on why we should focus on burdens, and why burdens might still make a difference even in interventions like AVR.

Why focus on burdens and not just turnout?

The centrality of election administration in policy discussions since the 2000 election reflects an assumption that election policies have partisan effects on turnout. But our standard for evaluating new voting laws and administrative practices should not only be “do they reduce turnout?” or “will they benefit one party?” but rather “do new laws impose pointless burdens on voting?” and “are those burdens targeted toward some groups more than others?” A good law should create benefits for the public and avoid unnecessary costs. Many election laws are restricting clear benefits to voters — convenience and access — while imposing pointless new costs upon them.

I’ve argued for focusing on burdens rather than turnout for a few years now, because I think burdens are inherently important. Indeed, the first chapter in my book with Pam Herd about administrative burdens centered on election. A provocative new paper by Justin Grimmer and Eitan Hersh has solidified my thinking. They argue that election laws are unlikely to generate partisan effects is because they often only affect a small group of voters, and that small group may be relatively bipartisan. However, that does not mean we should ignore the effects of election laws even if the turnout and partisan effects of election laws are limited.

Research shows that such laws can engender significant changes to learning and compliance on the voters affected, often minority voters. For example, non-white voters are less likely to receive helpful information about new voting laws, suggesting a bias that resulted in higher learning costs for such voters. Racial and ethnic minorities were also the most likely not to have IDs that would satisfy new election laws, meaning they bore greater compliance costs. We know that new voter ID laws do reduce turnout for those voters who previously lacked an ID, suggesting that the effects of compliance laws are specific to those who have to do the most to comply with new laws.

In short, election laws can still create new burdens, and even burdens that fall on some groups more than others, even if they don’t affect aggregate turnout or have partisan effects. The implication is that the effects of new voting restrictions may be best detected by looking at the burdens that are created, and how those burdens are distributed. Voter turnout is only one, and perhaps not the best, measure of the effects of laws that impose burdens on voters. Measuring administrative burdens provides a more direct measure of the effects of these laws, which may or may not result in changes in turnout.

Minimizing burdens through automatic enrollment

For the past thirty years, the federal government has encouraged easing registration processes. The National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), also known as the motor voter law, was built around the logic that the state should use a wide array of citizen-state interactions with citizens to make registration easier. The law encouraged the use of DMVs as a site of registration, but other parts of the NVRA were less widely applied, including agencies providing welfare benefits to provide voter registration opportunities. However, the minimum processes required by the NVRA still leave burdens in place for registration. While state agencies are required to offer customers the opportunity to register to vote, such registration is only required to occur on an opt-in basis, and individuals must assess their own eligibility and are typically asked to provide additional information or duplicate information already provided to the agency in order to complete the form. While the NVRA has improved registration opportunities at state agencies, it still leaves in place administrative burdens for those seeking to register.

Partial or front-end automatic voter registration

Roughly half of the states with AVR have what is sometimes described as partial or front-end AVR, including the newly adopted AVR system in Pennsylvania. Here, people at a DMV or other covered agency are told that their information will be used for voter registration (or updating of any existing registration), unless they opt-out. They are then presented with the option to decline registration. Partial AVR (PAVR) has increased registration and turnout. But it still leaves a significant amount of friction in place, requiring more effort to complete the registration process at that particular moment, even if it means minimizing effort compared to the basic NVRA system where DMV customers must affirmatively select a voter registration option.

Burdens still exist in a partial AVR system. Customers must answer questions during the transaction – about whether they want to register, about their eligibility to register, and various voting preferences, including party affiliation, mail ballot options, or language preference. DMV customers, believing that these voter registration questions will lengthen the transaction, may want to complete their primary business and move on, to the point that many will not take any extra time to register to vote, or verify their registration information.

A large share of eligible customers can decline unnecessarily due to imperfect information, because they incorrectly believe they are already registered to vote or that their registration is current, or because they are unsure of their status, in the case of teenagers, and individuals with past felony convictions. Other individuals may be confused about why they are being asked about voter registration at the DMV, or trust themselves to register or update their information later when they have more time. In a study of the PAVR process used by Colorado from 2017 to 2020, Grimmer and Rodden find that more than 70% of unregistered and potentially eligible people were opting-out of voter registration, even when presented with a default voter registration opportunity as part of their DMV transaction. Similarly, they found that one third of existing registered voters who declined to update their registration had out-of-date registration information and actually needed to update.

Secure or back-end automatic voter registration

A back-end or secure AVR (SAVR) approach creates a more frictionless process for registration than a PAVR system, and requires that an eligible individual make more effort to opt-out of the registration process than to be registered.

A SAVR system uses administrative data from state agency transactions to establish eligibility and automatically register clearly eligible individuals, while affirmatively filtering out ineligible non-citizens. Again, there does not have to be a tradeoff between greater election security and reducing burdens. If the state can establish a person’s eligibility (including definitive proof of U.S. citizenship) based on the information provided as part of a DMV or other agency transaction, the person is automatically registered. Similarly, any existing registered voter has their information updated based on address and name information provided to a state agency, to ensure that address and name records reflect the information most recently provided by the voter. Following an agency transaction that results in a new registration or a registration update, affected individuals are sent a mailer advising them of the change and providing a prepaid return mailer that allows them to opt-out or correct any information.

In the past eight years, Oregon, Colorado, and Alaska set the benchmark for this approach, which has now been adopted in six more states, and relies on structuring choice architecture to favor registration. In Colorado, which shifted to SAVR in 2020, fewer than 1% of people who are automatically registered to vote return the opt-out mailer, resulting in a system where registration is the strong default for anyone the state knows is clearly eligible to vote. Only individuals who truly do not want to be registered to vote take the additional step of returning the post-transaction mailer, whereas the remainder of the covered population remains registered without any additional effort required on their part. These individuals are free to vote, if they wish, with registration having been accomplished through an essentially frictionless process. Changing the default to a post-transaction opt-out relative to within transaction opt-out had a large effect at DMV voter registration in Colorado, significantly decreasing the number of voters who opt out, and effectively doubling the registration rate at the DMV, with disproportionate impact on younger voters. These are very large effects for relatively low costs, an estimated $86,000 to implement the new system.

According to the Colorado Secretary of State: “Registering to vote and voting itself should not be a burden. These are our constitutional rights. State governments should be seamlessly offering potential voters the option to register.” This reflects the basic assumption that underpins automatic enrollment: where it can, the government should eliminate frictions to valued rights and services.

In a SAVR system, learning and compliance costs for registering to vote are effectively eliminated. Eligible voters are automatically registered to vote or have their registration updated to reflect the most current information available, and are then informed of the change and provided an opportunity to decline. The decline in burdens and potential impact on voter registration is greater than in a PAVR system.

Some SAVR states have also sought to use Medicaid data to automatically register eligible voters who enroll in Medicaid. Like SAVR at the DMV, this approach builds on the requirements of the NVRA, which requires a voter registration opportunity as part of Medicaid enrollment. However, these states have faced implementation roadblocks due to a lack of clear guidance from the federal Department of Health and Human Services on how Medicaid data can be used in this fashion.

If you want to increase trust in elections, reduce burdens; if you want to decrease trust, lie about fraud

Those arguing for more burdensome requirements to reduce election fraud face the two-fold problem that a) there is little fraud to reduce, and b) new restrictions are often unrelated to fraud. It is, therefore, unsurprising that making elections more onerous does not increase trust in elections. States with ever more burdensome voting procedures do not have higher trust in their elections. For example, the addition of voter ID did not increase trust in elections. Indeed, we have much stronger evidence that claims of widespread fraud, even if unsubstantiated and even if corrected by fact checkers, are what drives declines in confidence in elections.

One way to actually improve confidence in elections is to make the process functional and accessible for citizens. Voters tend to agree in very high numbers (above 95%) that voting was a positive experience with minimal problems. Such surveys exclude non-voters, and so we know little about how negative experiences discourage any sort of participation. But it is clear that confusing or negative experiences are correlated with declining trust. According to Charles Stewart III:

Among the 94 percent of in-person voters who agreed their experience was mostly positive, 94 percent were confident their vote was counted as intended; for the 6 percent who had a negative experience, only 68 percent trusted that their vote was counted as intended.

An election system that took seriously the principles of administrative burden theory – that citizen-state interactions should be simple, accessible, and respectful – would do more to actively broaden who participates through tools like fully streamlined AVR, while doing away with pointless roadblocks that predictably trip-up the average voter.

The claim that non-citizens were registering unchecked in vast numbers was a theme of the Trump re-election campaign, mixing both xenophobia and false claims of massive election fraud. All people registering to vote must attest they are citizens and eligible to register. If non-citizens lie, they risk prosecution, loss of citizenship, and even deportation. Which is why this is extraordinarily rare. In other words, self-attestation under risk of prosecution is a good balance between maintaining integrity while not over-burdening voters. In a federal court case where Kansas sought to add citizenship documentation requirements, it could point to, at most, 67 non-citizens who had registered or even attempted to register to vote over the course of 19 years. Additional documentation burdens would predictably exclude vast number of citizens who could not easily obtain such documents. More than 31,000 citizens had their registrations suspended for not providing such documentation in Kansas over a relatively short period. The courts decided that the very remote risks of non-citizens voting did “not justify the burden imposed on the right to vote.” Nevertheless, Republicans in Kansas are determined to try the policy again in the hope that the more conservative SCOTUS will once again abandon precedent.

When a baby is born in the US the parents can easily request a Social Security number for the child and most parents do this. Each state records births. These infants are US citizens, not other proof required. Why can't this information be used to automatically register a child to vote on their 18th birthday? Obviously, the system would have to verify a local address so the person is registered to vote in the proper location but computers can actually be programmed to do remarkable things.