About Time - Part II: Cutting the Time Tax Created by Government

Five Lessons from Biden's effort to reduce administrative burdens

In a previous post we explained the Biden-Harris “Time is Money” agenda that aims to stop private organizations from imposing unnecessary hassles on the public. In this post, we focus on what the Biden administration has been doing to reduce burdens imposed on the public by the government. This agenda emerged early in the administration, and real progress has been made. As a result, it becomes easier for the federal government to tell the private sector to reduce administrative burdens when they are walking the walk.

A new report tells us about the progress the federal government is making, declaring that “reducing burdens to access public benefits and services is a central priority for the Biden Administration.” The report comes from the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, best know for performing cost-benefit analyses of regulations on businesses. Under Biden, OIRA has directed more attention to the experiences of burdens by members of the public. This is the second annual OIRA report on burden reduction. We wrote about the first report here.

The report offers some additional insights about how burdens matter to governing. Here are five that jumped out to us.

Lesson 1: Changing the Narrative on Fraud

Over the past three and a half years, a mixture of executive orders, rule changes, and OIRA guidance has pushed federal agencies to shift their perspective about how they should engage with the public. One particular change is how fraud is considered. Claims of fraud have traditionally been a trump card in justifying more onerous procedures, even when the risks are low and the procedures offer little value. OIRA is pushing for a more nuanced perspective on trade-offs between fraud risks and burdens:

While efforts to reduce administrative burden are sometimes cast as in tension with the goal of maintaining program integrity–that is, ensuring that the government delivers benefits and services only to eligible individuals, in practice this is rarely the case. Reducing administrative burdens, ensuring program integrity, and preventing wasteful spending, often go hand in hand.

For example, OIRA points out that a key advantage to automated program enrollment or renewals is not just that they reduce burden, it actually improves programmatic integrity by drawing on administrative data rather than less reliable self-reports. Social Security’s retirement program is one of the best examples of this very point. It is our least burdensome social welfare program. The process of collecting and verifying employment earnings is handled entirely by the government and your employer. It is also a program with high programmatic integrity. It shows how looking for “win-win” strategies that can both reduce fraud and burdens is possible, if government has the capacity to implement those strategies.

Lesson 2: Don’t Make People Feel Bad

OIRA highlights the need to address psychological costs created by government, not something usually front of mind when public service delivery is designed:

Administrative burdens do not just keep eligible individuals from accessing programs; they also sap Americans’ trust in the ability of government to meet their basic needs or operate efficiently.

An example: the OIRA report highlighted recent changes to the Supplemental Security Income program, which supports the elderly, blind and disabled. The program is means-tested and notorious for its bevy of burdens. One such example is a requirement that beneficiaries report any food assistance they received from family or friends. If a neighbor brings over a bag of groceries, you have to report it. If an elderly woman's daughter regularly brings her mother lunch, she needs to report it. Failing to report, a confusing process in and of itself, can lead to a ‘clawback’ or requiring beneficiaries to pay money back to the government.

Given that federal SSI benefits max out at 76% of the poverty level, or $943 a month for a single person, the requirement is mean spirited. SSA agreed and ended the reporting requirement. Here is what the OIRA report described:

SSA highlighted the distinctive psychological costs of food reporting. SSA acknowledged that questioning individuals about something as personal as food could be seen as too intrusive. Moreover, the previous policy of categorizing food, a “common human generosity” as something that must be reported might cause SSI recipients to experience frustration, anxiety or other forms of discomfort. As with the complexity of the reporting requirement, the psychological costs…may ultimately result in people choosing not to apply for SSI. As SSA noted, the change “has the potential to make our rules less intrusive and better protect peoples’ privacy and dignity.

OIRA laid the groundwork for this change in 2022 guidance, when it required federal agencies “to consider the psychological costs that information collections could impose on individuals.” As a specific example, they noted:

an application process that asks an individual to provide highly personal information about themselves or other household members without a clear explanation for how and whether this information is necessary to determine program eligibility may be perceived as unduly invasive. These factors, among others, can lead to individuals choosing to delay or abandon completing a form instead of gaining access to a benefit they are legally eligible to receive.

The capacity to recognize that not every basic human interaction needs to be formalized into a reporting requirement, and to be sensitive about how it solicits unnecessary information, enables a government to be slightly less bureaucratic and slightly more humane. The SSA is one of numerous examples where agencies are using their discretion to recreate categories or rules to better fit with how Americans actually live their lives.

Lesson 3: Make it Automatic

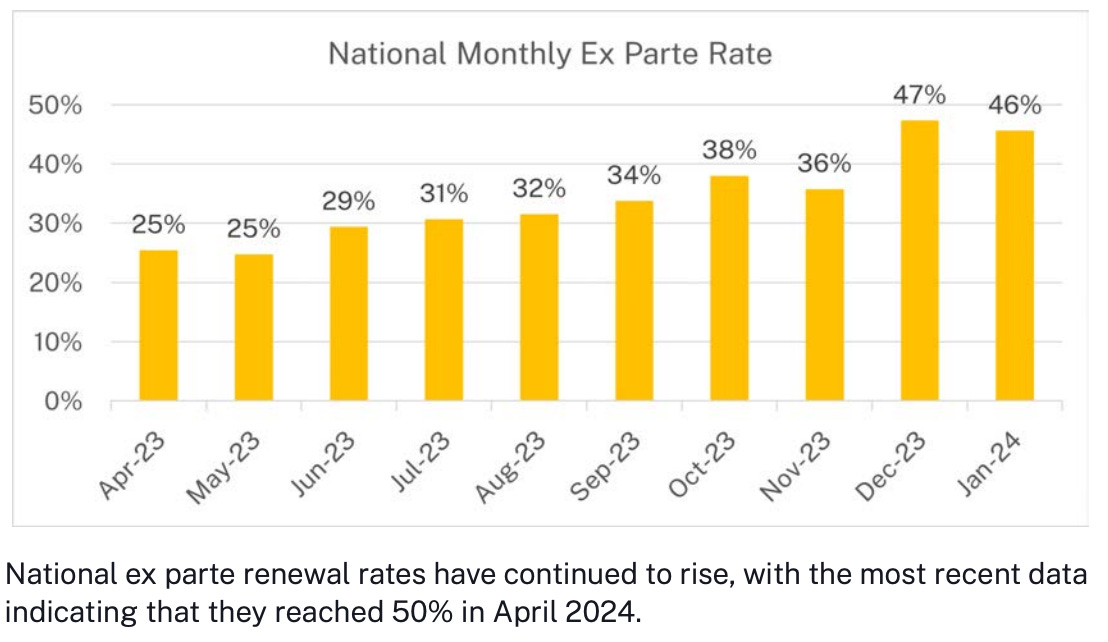

State governments are under a legal obligation to pursue automatic renewal for *all* individuals on Medicaid, using data that the state can access on its own. There is a good reason to use such ex parte renewal processes. Beneficiaries often spend enormous amounts of time and effort filling out forms and providing documentation to show they’re still eligible for Medicaid. And many eligible clients end up not completing the process, because it's too complicated, confusing, or they don’t receive the notification that they need to do so.

Automated renewals can fix that problem. But traditionally there is enormous variance in implementation: some states automatically renew as many as half of Medicaid clients, others renew as few as 1 in 10. This became a huge issue with the end of the public health emergency, when states had to deal with the largest ever population of Medicaid renewals.

The good news is that states have improved their ex parte rates, and the US Digital Service, and the Department of Health and Human Services are claiming some of the credit, reflecting their outreach to specific states, and encouragement to seek waivers to increase access. USDS officials also worked directly to improve ex parte processes for eight states, and claim that 5 million additional people maintained Medicaid coverage as a result. On average, automated renewals doubled over the course of a year.

These coverage savings come in the context of a massive loss of Medicaid coverage, underlining the degree to which routine annual processes where people have to show they continue to be eligible is a big tripping point for people who want coverage. More broadly it underlines a big lesson from research on burdens: informational nudges help at the margins, but to really reduce frictions and increase take-up, automating coverage is the way to go.

Where automation is not possible, governments can still reduce burdens via other tactics: data sharing between programs with similar clients, expanding the use of standard deductions that require less documentation, extending certification periods between mandatory renewals, aligning criteria such as asset limits between programs. Each of these types of tactics were identified by OMB two years ago, and all are being deployed in practice now.

Lesson 4: Burden Reduction to Improve Equal Opportunity

One of the elements of the Biden’s burden reduction efforts term is the idea that reducing burdens is a mechanism to reduce inequality. So lets focus on one process where this plausibly plays out, which is presidential pardons.

Many more people apply for pardons than receive them, and we generally only hear about pardons in cases where there is reason to suspect close ties, or financial interests between the President and the applicant. For example, Trump pardoned his long-term political boosters Roger Stone, Steve Bannon, and a host of others with ties to him or the Republican Party.

Less well known is that the pardon process itself is administratively onerous, and almost impossible to undertake without legal help. Consider these two quotes for applicants in the pardon process.

When I first began reading through the current application, I was somewhat overwhelmed and wondered if I could do this on my own or if I should hire an attorney for assistance.

I got a stomachache and a headache just looking through the pardon application form.

Burdens in the pardon process make it harder for those who might have compelling cases, but lack political connections or financial resources to submit their petitions. In fact, a Rand analysis found that the vast majority of pardon applications were incomplete, making it less likely they would succeed.

To reduce burdens, the DOJ simplified the language of the form, reduced the number of questions, the degree of detail required, notarization requirements, and explained the need for sensitive questions that could not be eliminated. It offered space for individuals to present their own narrative. As in multiple programs, the use of plain language and human centered design is touted as central to these changes. These might seem like small changes, but they make the process of accessing clemency a little fairer. We hope that the DOJ tracks how these changes matters to future applicants.

Lesson 5: Burden Reduction Must Be Co-produced by The Public

Writing about the new report, Sam Berger of OIRA calls for public input. One thing we have been pleasantly surprised about is the degree to which such pleas for public comments are sincere. For example, the quotes by the pardon applicants noted above were part of an information collection process tied to public comments.

OIRA provides guidance on how to weigh in on federal processes:

To share your views on government forms, you can visit OIRA’s website to see forms we are currently reviewing and that are open for comment. To make the process simpler, consider consulting OIRA’s guide to providing input on these forms. Your comments can make a difference, by helping us to understand the administrative burdens you face, as well as identify ways to address them.

This desire for public input also features in Biden-Harris efforts to reduce sludge created by private actors. The “Time is Money” announcement from the White House offered the public the chance to direct government attention to hassles.

What else should we take on? The White House is calling for Americans to share their ideas for how federal action can give them their time back. Interested parties can submit their ideas and comments at this portal.

Federal agencies take these comments seriously. Summaries of rule changes typically include reference to the comments they received, and they can change how rules are defined and implemented. Believe it or not, federal officials review all comments they receive, and typically systematically evaluate their content. This commitment to public input reflects the idea of burden reduction as a regulatory process co-produced by the government and citizens, one which is then better able to benefit the public more broadly, rather than just the well-connected.

Outstanding summary of some very good results towards reducing administrative burden in government. As you wrote "Social Security’s retirement program is one of the best examples of this very point. It is our least burdensome social welfare program." Having spent my professional career as an academic specializing in Federal tax law (PhD accounting) and as an associate dean in a business school I spent this career immersed in administrative burden, governmental and private. When I retired at age 69 and went to sign up for Social Security I was so very pleasantly surprised to find out how relatively easy it was. The process was also fairly quick. I had to talk to a representative twice, and these were both short conversations with a representative who was knowledgable and efficient. I'm on the autism spectrum and very introverted and I hate having to talk on the phone but both conversations went so well, and I understood why each one was necessary, that I did not have any objections. I've also found the SS website easy to navigate and quite helpful. I will add that I'm fairly vanilla and haven't had any problems with SS either before or after retirement; I never had a problem with employers reporting my earnings and never had any issues with identity theft. I did change my last name twice due to marriages, and then went back to my maiden name, but that's a fairly common occurrence. It's so nice when such a large government agency can work so well.