Ezra Klein recently wrote a provocative and thoughtful piece about administrative capacity in the modern American state. The key claim is summarized here:

I’ve spent most of my adult life trawling think tank reports to better understand how to solve problems. When I go looking for ideas on how to build state capacity on the left, I don’t find much. There’s nothing like the depth of research, thought and energy that goes into imagining health and climate and education policy. But those health, climate and education plans depend, crucially, on a state capable of designing and executing policy effectively. This is true at the federal level, and it is even truer, and harder, at the state and local levels.

So this is what I have become certain of: Democrats spend too much time and energy imagining the policies that a capable government could execute and not nearly enough time imagining how to make a government capable of executing them. It is not only markets that have failed.

At least two parts of this argument seem right to me.

We don’t pay enough attention to administrative capacity in general. (I study public administration, so I’m always up for more attention to this topic!)

Progressives are so devoted to policy design that they neglect administration, and then are surprised when their carefully designed policies don’t work.

From there I want to offer a set of stylized facts about American administrative capacity that are different in content, but similar in spirit to the ones that Klein offered. These claims are provisional — I could be wrong — but are plausible and not closely considered in Klein’s account, which does not pretend to be a comprehensive take on the topic. They incorporate some of my favorite research in this area, and some thoughtful responses from when I tweeted a bit about the topic.

Administrative capacity may be too broad a unit of analysis, but we should talk about it anyway

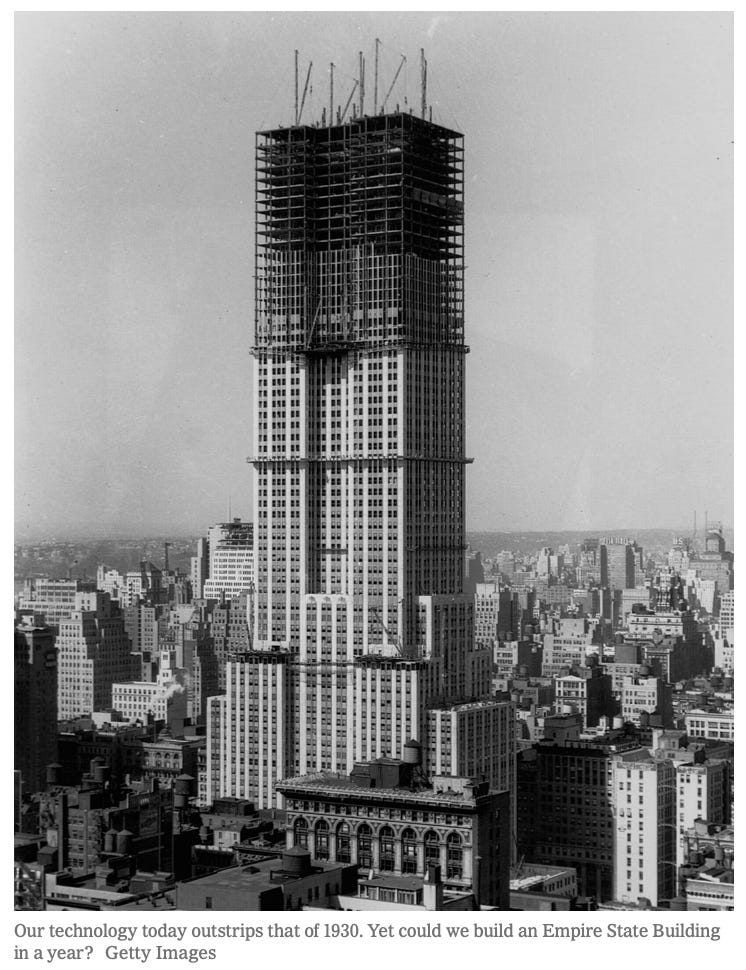

Klein measures the decline of American administrative capacity in terms of our ability to build stuff. He points out how much more expensive it is to build rail in the US compared to other countries and shares photos of a yesteryear when America was capable of building the Empire State Building in a year. This is a common concern. Subways, buildings, or other major infrastructure takes too long to build and costs too much, and liberal enclaves like New York or California are no exception.

Such comparisons are useful. But they also raise the question of how we think about capacity across administrative functions and tasks. In some areas, US administrative capacity remains world-beating, most obviously the military, which enjoys bipartisan and popular support, and vast investments of resources.

The US administrative capacity problem is not uniform then. Moreover, the root of capacity problems may differ from one task to another. The reasons why it’s hard to build stuff may be different from why our health care is inefficient, or why we can’t collect taxes.

The Niskanen Center, which Klein draws inspiration from, uses a definition of state capacity as “the ability of a state to collect taxes, enforce law and order, and provide public goods.” Sean Gailmard, a political scientist at UC Berkeley who has written about how governments maintain expertise, raised the question of whether this definition was so all-encompassing as to not be terribly useful for public functions which operate under very different conditions.

I share the misgivings about “administrative capacity” as a unit of analysis. It feels so broad that it becomes victim to the problem of conceptual stretch: if administrative capacity is everything, maybe it’s nothing.1

But the term is useful if only because it pushes analysts, researchers, and policymakers to think about the big picture in a way we typically don’t. A reasonable critique of much of the scholarship on American public administration is that it is focused on the micro level (think behavioral analysis of the individual) and sometimes meso level (e.g. public employment systems), but fails to connect to a macro picture that deals with what Alasdair Roberts characterizes as “strategies for governing.”

Some of the decline in administrative capacity is a political choice

Going back to the example of tax collection, the story of declining capacity seems fairly obvious: we don’t invest in administration, partly due to ideological opposition to the ability of government do its job. Brink Lindsey neatly sums up this ideology and its base:

…a radical libertarian ideology that went beyond mere skepticism about government expansion and instead condemned the entire public sector as inherently dysfunctional and morally illegitimate…libertarianism’s heated anti-statist rhetoric aligned nicely with the interests and predispositions of important and powerful constituencies—first, the business community, which had massively expanded its lobbying operations in response to the equally dramatic expansion of federal regulatory activity; next, the growing “donor class” of extremely wealthy and extremely tax-averse individuals, whose numbers expanded with rising income inequality and the increasing skew of incomes toward the top end; and finally, members of the white working class, whose growing cultural alienation from governing elites came to eclipse their awareness of their considerable economic reliance on government spending programs.

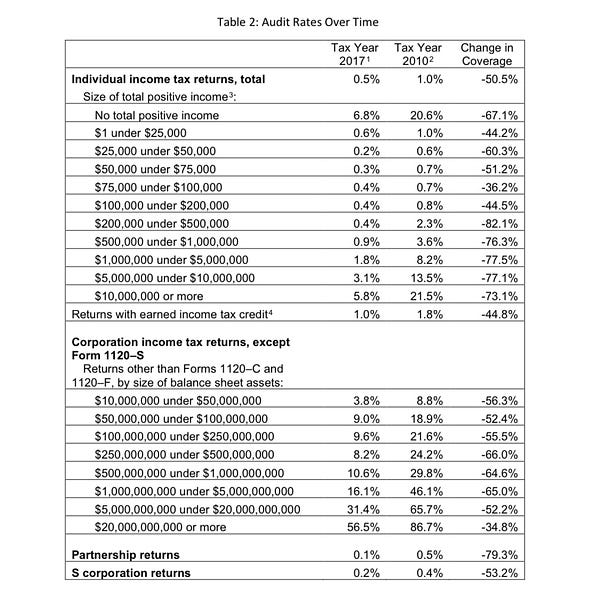

You don’t have to look hard for examples. There are simply fewer federal government employees relative to the tasks we ask of them. As a percentage of the population, the federal workforce was 1.13 percent in 1967 but shrank to 0.64 percent by 2018. We see a similar decline with the IRS, which deals not just with a more complex tax code, more taxpayers and increasingly the provision of social programs like Child Tax Credit and EITC even as the agency itself keeps shrinking.

The results are predictable. The agency currently has one staff person for every 16,000 calls it gets, and increasingly gives a free pass to the wealthy who engage in cheating.

New IRS spending would more than pay for itself, and yet Republicans routinely call to further gut it.

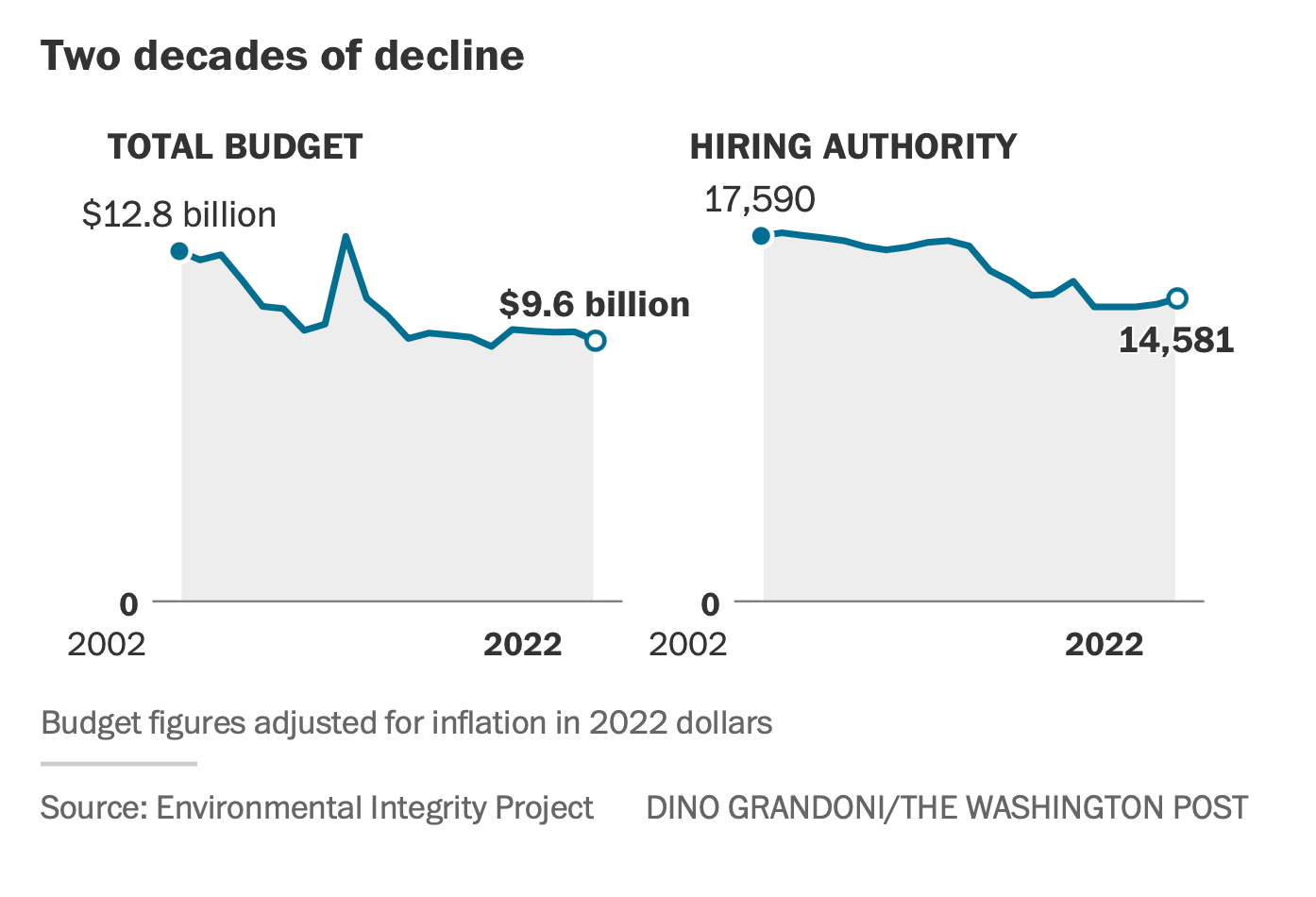

Let’s take another example: We are in the midst of a climate crisis, but have fewer climate scientists and resources in the Environmental Protection Agency than we did 20 years ago.

While Republicans are the political actors most responsible for this source of administrative decline, the Democratic preferences for policies over administrative matters means they don’t treat administrative capacity as a priority, seemingly failing to understand in a way that Republicans do that progressive goals depend on a capable state.

A “procedure fetish” or judicialization of the administrative state?

Another suspected source of administrative decline is what Nicholas Bagley bemoans as a “procedure fetish.” Here is how Klein summarizes Bagley’s explanation of the source of this fetish:

He suggests, provocatively, that that’s because American politics in general and the Democratic Party, in particular, are dominated by lawyers. Biden and Kamala Harris hold law degrees, as did Barack Obama and John Kerry and Bill and Hillary Clinton before them. And this filters down through the party. “Lawyers, not managers, have assumed primary responsibility for shaping administrative law in the United States,” Bagley writes. “And if all you’ve got is a lawyer, everything looks like a procedural problem.”

The clear implication is that politicians, especially progressives, have a taste for procedure over outcomes, and embed that preference into our governance. I am not sure that this is the right causal story. Lots of state administrative systems are dominated by lawyers, some more than the US. Germany is a prime example, and is also one of the example Klein points to as a country better able to build stuff.

An alternative account is that in the US the courts have increasingly claimed supremacy over administrative matters (which Bagley acknowledges), compelling agencies to become more judicial in their actions. There is even a term for this: judicialization.

A new paper by Scott Limbocker, Jennifer Selin, and Bill Resh offer evidence of judicialization. They find that as agencies are increasingly exposed to the courts via litigation, they invest more in legal staff. This finding is not just a function of the task of the agency: it holds true even within agencies over time. The authors spell out the basic logic here:

Because the judicial branch lacks the technical and institutional capacity and incentives to micromanage the substance of thousands of bureaucratic decisions issued on an annual basis, courts emphasize procedural considerations (Bressman 2007; Stephenson 2006). The underlying logic of modern judicial doctrine is that agencies should “eschew quicker, less inclusive decision-making in favor of more intensive, multipolar forms of deliberative rulemaking” (Michaels 2017, 183). Agencies graft those preferences onto bureaucratic structures so that agencies can, in turn, appease the courts. Agencies have adopted more extensive administrative procedures, strategically adjusted the timing of regulatory decision making, and supplemented administrative records with technical and legal information to ward off litigation.

In other words, the emphasis on procedure is less a political preference than a strategic response to the courts. The courts value individual rights, formalism and due process. They care less about administrative capacity or outcomes. The increasing supremacy of the courts therefore comes at the expense of state capacity.

A very good example of this comes in the form of a recent 5th Circuit decision that essentially gutted the ability of the SEC to do much of its job. In Jarkesy v. Securities and Exchange Commission, the court ruled that the SEC’s use of administrative hearings violated the right to a jury trial, and therefore was unconstitutional. This is a major break from almost a century of precedent that accepted that the SEC could employ administrative hearings and administrative law judges.

From an administrative capacity perspective, the decision makes it extraordinarily difficult for the SEC to regulate industry. The decision is symptomatic of a skepticism of the administrative state more broadly among conservative jurists which is likely to undermine state capacity in the coming decades. The National Law Review, not a publication given to hyberbole, put it this way:

The decision also calls into question nearly all administrative agency action. Dozens of federal agencies use similar processes, including the Environmental Protection Agency, Commodity Futures Exchange Commission, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Federal Trade Commission, and National Labor Relations Board. Should the decision stand, it is likely dozens of lawsuits challenging the administrative actions of these other agencies will follow.

If my interpretation is right, the Republicans who are creating administrative dysfunction described above are also contributing to declining state capacity by picking judges inherently suspicious of administrative power. This seems like a bigger threat than the preferences of Democratic lawmakers with legal backgrounds.

Let me sketch out more briefly three more hypotheses on why US administrative capacity has been in decline in certain areas.

Hypothesis 1: Private participation is an essential part of state capacity, but can result in capture and rent-seeking

The historian Brian Balogh argues that the development of the American state has always depended upon public-private partnerships. Such partnerships both serve to hide the role of the state in ways that both allow myths of rugged individualism while taking advantage of non-public expertise. For the motivating example of building stuff, such partnerships are essential. The government does not generally build stuff. At most it’s involved in public private partnerships, and regulates the conditions of work. The standard hypothesis is that excess regulation, including multiple veto opportunities for opponents of construction slow the process, disrupt such partnerships and drive the decline in capacity.

I want to suggest a different hypothesis: it is harder for governments to maintain control over public-private partnerships when the private partner can convert their market power into political power. In the US, this conversion is very easily done. In recent decades, corporations who serve as the private partner have been offered more opportunity to give money to policymakers who decide on the conditions of their partnership. Their employees can become political appointees for a spell. They can hire their current government overseers to lucrative post-government careers.

Public-private partnerships work well when the goals of the government and private actors are aligned, but that becomes a more difficult when the private actor can rewrite those goals for the purposes of rent-seeking, extracting private benefits from arrangements intended to help the public.2 For example, the tax-preparation industry undermined a partnership with the IRS to provide free tax e-filing. I don’t know how common this phenomenon is, but the underlying logic of the conditions of capture and rent-seeking are straightforward.

Hypothesis 2: Federalism undermines administrative capacity

When I moved to the US, I was intrigued by the idea of states as laboratories of democracy, but the more attention I’ve paid to federalism, the more persuaded I am that they are instead laboratories of dysfunction.

In the 1930s, federal policymakers talked about making Unemployment Insurance a federal program like Social Security. Does anyone seriously doubt that a federal UI system would be better run than the state-run versions that collapsed during the pandemic? More decentralized administration is harder to monitor, more vulnerable to threats from interest groups who are mobile, and adds another veto player at the state level that can essentially kneecap an intergovernmental policy they dislike. (See this discussion from Jamila Michener and Jake Grumbach). If one complaint about US administrative capacity is that it is too responsive to the public, the experience of federalism hints at the opposite claim: insularity from traditional processes of accountability make them less effective, laboratories against democracy as Grumbach puts it.

Hypothesis 3: Data-sharing concerns and lack of investments in technology reduces capacity

One big insight from my research on administrative burdens is that underinvestment in technologies and tech capacity, and legal prohibitions against data-sharing are a big problem for the US administrative state. There is no real way to square the fact that the US is the home of Silicon Valley, but many parts of the government rely on decades-old technological infrastructure. Moreover, limitations on data-sharing make the government unable to fully exploit technology, even when it would benefit users. For example, we can’t do basic things like target student loan forgiveness to lower earners using administrative data without changing the law.

There is growing philanthropic interest about how “civic tech” can fix government. For example, Code for America, a nonprofit, recently raised $100M to help states with their social safety nets. The need for their role speaks to the gap in governments to address these problems, the failure to cultivate a certain type of administrative capacity for the digital era.

A conversation worth having

The final thought is that the conversation that Klein elevated is one well worth having, and I hope others respond in the same spirit. It connects to even broader questions, like whether liberal democracies can still do big things to satisfy citizen expectations. There is also issue of how to fix the capacity problem. But these are topics for another day.

If you enjoyed this, chances are you will enjoy reading the archive with posts about the Biden administration’s efforts to reduce administrative burdens, as well as new research on the topic. Please subscribe if you have not already, and consider sharing.

Some more concerns about the use of administrative capacity as a term raised by Martin Williams of Oxford University here. In general, some of the best research on administrative capacity comes from researchers like Williams looking at developing country settings.

Private partners have their own gripes, many justified, about the unreliability of public partners, and their inability to define their goals in a consistent fashion.