Here is one way to understand America today. A group of wealthy people were deeply unhappy about democratic institutions holding them accountable. So they set out to make them less democratic and less powerful. They used their money to make money the most essential currency in this democracy, more important than votes.

How did they succeed?

They realized that politicians, while valuable, could be unreliable. Better to capture the least democratically accountable seat of public power — the courts — and use that to weaken public oversight over their interests.

The decisions this week represent the culmination of some long-held goals. With Loper Bright, SCOTUS have dismantled Chevron deference and regulatory powers. Chevron deference is the judicial shorthand for the idea that as Congress writes vague laws (because it cannot anticipate every aspect of the law that needs to be specified), judges should defer to experts in the federal agencies to fill in the gaps. In 1984, John Paul Stevens wrote in a unanimous ruling establishing “Chevron deference” that “Judges are not experts in the field and are not part of either political branch of the government.”

Forty years later, the Roberts court disagrees. They believe they are experts enough in the field to second-guess agency officials. They welcome the opportunity to side with moneyed interests who have the capacity to bring such legal challenges. In her dissent, Justice Kagan declared: “In every sphere of current or future federal regulation, expect courts from now on to play a commanding role. It is not a role Congress has given them…It is a role this court has now claimed for itself, as well as other judges.”

The demise of Chevron is being widely interpreted as an expansion of judicial power. It is that, but it also and more profoundly an expansion of power of moneyed interests.

How big of a deal is this? We can measure this in a variety of ways.

First, how much case law is dependent on Chevron? Some 70 Supreme Court and 17,000 lower court decisions. Agencies will be more reluctant to use regulatory power in the future, knowing that the best resourced actors will challenge them in court, and will find a sympathetic audience in the Roberts court. Which is the point, since corporations and the Republicans they donate to, and which selected the majority, want fewer regulations.

Second, we can look at how much administrators rely on Chevron it to make judgements. My Georgetown colleague Mark Richardson recently wrote about this.

A shift in responsibilities from agencies to courts would be a fundamental change in the relationship between Congress and agencies that undergirds the modern administrative state. A survey of Congressional staffers found that a majority (58%) consider Chevron deference when drafting statutes. A similar survey of civil servants responsible for writing rules found that nearly all respondents (90%) reported that Chevron “play[s] a role in [their] rule drafting decisions.” These results illustrate the fundamental role of Chevron deference. Congress considers it when drafting statutes that delegate to agencies and civil servants consider it when interpreting those statutes to write regulations that implement laws.

Third, consider the range of policy impacts. The New York Times offered an explainer about how the fall in Chevron — centered on a case where government officials could charge boats that they were inspecting a fee — would have massive potential consequences in a wide range of policy domains.

“The result would quite likely be that stringent climate rules designed to sharply reduce emissions could be replaced by much looser rules that cut far less pollution. Experts say that could also be the fate of existing rules on smog, clean water and hazardous chemicals.

The elimination of the Chevron deference could affect workers in a variety of ways, making it harder for the government to enact workplace safety regulations and enforce minimum wage and overtime rules.

Abortion opponents say the ruling could work in their favor as they seek to bring another case against the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of an abortion medication to the Supreme Court, which rejected their effort to undo the agency’s approval of the drug this month.

The court’s ruling could affect how Medicare, Medicaid and Affordable Care Act insurance plans are administered, health law experts said, as opponents gain an opportunity to challenge how these huge programs operate.

Although Congress creates the tax code through legislation, the I.R.S. has wide latitude in how the tax laws are administered. Accounting experts have suggested that the court’s ruling could complicate the agency’s ability to administer the tax code without specific direction from Congress.”

Ask yourself, how confident are you that the current Congress will step in to fix the problems that arise in these policy areas? And what sort of vision will the Supreme Court impose as they have become policymaker-in-chief?

While Loper Bright is deservedly getting most of the attention, two other decisions further enhance the power of moneyed interests. The Jarkesey case, which involved a right-wing radio host accused of defrauding investors. The SEC investigated, fined him, and barred him from the industry. Jarkesey claimed that administrative law judges had no such power, that he deserved a full trial, and the court agreed.

With the Corner Post decision, the same 6-3 majority extended the statute of limitations to sue regulatory actions not from when the regulations were put in place, but from when the plaintiff claims they were injured. This essentially means that the Loper-Bright decision is retroactive, as businesses can go back through old regulations they dislike the most, and bring them to the court.

How we got here

In 1971, Lewis Powell wrote a memo that bemoaned the attacks on business interests. But he also mapped out a response.

Strength lies in organization, in careful long-range planning and implementation, in consistency of action over an indefinite period of years, in the scale of financing available only through joint effort, and in the political power available only through united action and national organizations.

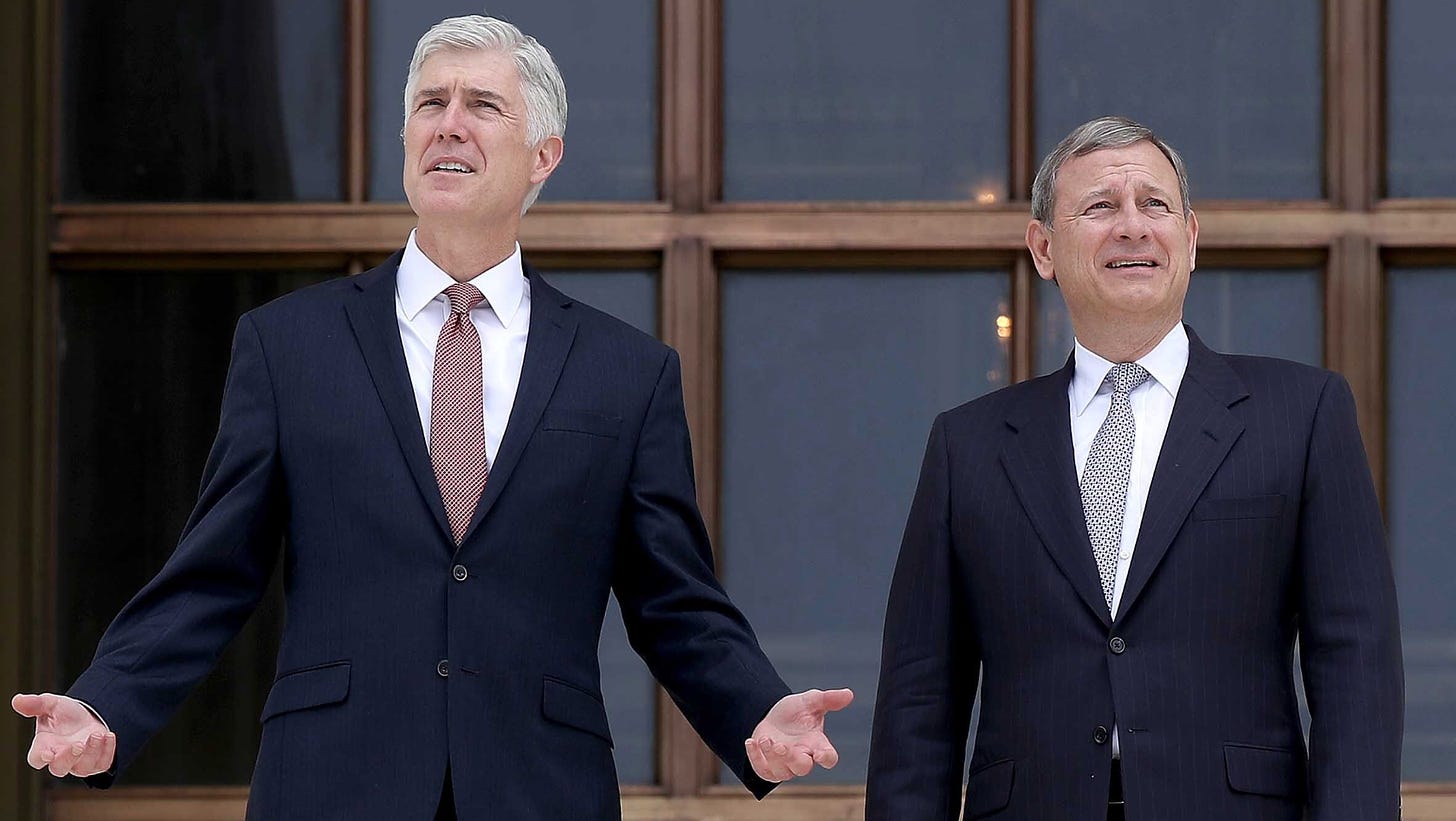

The Powell doctrine offered a roadmap by which money could became organizational and political capacity, and then, political power. Citizens United in 2010 was a key step to expanding the reach of money. The decision unshackled the very rich from any limitations in how they could use their money. As money became more valuable as a political tool, its ability to facilitate institutional capture grew. After the Citizens United decision, and the dismantling of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, Chief Justice Roberts directed attention to where he saw the real threats to democracy: “the danger posed by the growing power of the administrative state cannot be dismissed.” Associate Justice Gorsuch wrote that Chevron allowed “executive bureaucracies to swallow huge amounts of core judicial and legislative power.”

The Federalist Society, a private organization formed in 1982, represented the judicial realization of Powell’s roadmap. (Powell himself would become a Supreme Court judge). The Society quickly became a pipeline of conservative political appointees in Republican administrations and judicial nominees. It developed an elaborate operation to recruit and train law school students and sitting judges, direct them toward right-wing policy positions, and reinforcing that influence through ongoing retreats, training and events for judges. The majority of the Supreme Court are now affiliated with the Society. Since its beginning, the Federalist Society been supported by corporations and right-wing donors opposed to the regulatory powers employed by the administrative states. And the Federalist Society centered its energy on dismantling administrative power.

The Federalist Society is funded by and part of a broader right wing network of money, part of the “joint effort” that Powell imagined. They succeeded not just in mentoring lawyers in adopting an anti-Chevron position, they also screened them for fealty to this position when selecting Supreme Court judges. Don McGahn, the Federalist Society member who vetted Trump’s Supreme Court nominees, focused on Chevron in selection processes, saying:

It’s part of a larger, larger plan, I suppose…There is a coherent plan here where, actually, the judicial selection and the deregulatory efforts are really the flip side of the same coin.

They even managed to change the mind of some judges. Clarence Thomas had once been an ardent proponent of Chevron, the lead author of a 2005 decision that expanded the precedent. But years of spending time in the company of its opponents coincided with Thomas aligning with their views. He denounced Chevron in 2020. Now he frequently bemoans that agencies should not be give quasi-judicial powers, saying that Chevron: “wrests from Courts the ultimate interpretative authority to 'say what the law is' and hands it over to the Executive.” The Koch network staff found a case in Loper Bright that would allow Thomas to put his newly found beliefs into practice.

Less accountability to the public interest, more accountability to donors

Critics of administrative power denounce public officials as “unelected bureaucrats.” Which is sort of the point. They are unelected to provide some protection against the corrupting influence of money. Today, it is impossible to get elected without money. And our federal judges are then selected by those elected officials, having been screened and cultivated by moneyed networks over decades. As money became more central to politics, administrative insulation from politics became more important, and more threatened. The attack on bureaucracy represents an effort to dismantle or control the institutions that money has least control over. Threats like Schedule F, which aim to politicize the bureaucracy, are one part of that attack. Reducing administrative power is another.

This point was illustrated by Jarkesey, who claimed that internal adjudicator who heard his case of about financial mismanagement of a hedge fund had too much independence. Writing in The Atlantic, Noah Rosenblum, a Professor of constitutional law at NYU, described this claim as “galling”:

These adjudicators should be independent; the alternative would be to put their regulatory powers at the political whim of whichever administration might be in charge. They have long enjoyed some protection from removal, in order to insulate them from threats of reprisal.

I reached out to Rosenblum and asked him about how the two decisions will affect governance in the United States.

By overturning Chevron, the Supreme Court has undermined agency authorities and offered a major gift to those who seek to contest regulation. Agency enforcement will be chilled, since agencies will be less certain about the reach of their powers. And regulated parties will be emboldened to challenge all agency activities in court, raising the cost of regulation and hamstringing regulators. This will make it harder for democratic institutions to hold private interests accountable. The Loper-Bright decisions amounts to an invitation to judges to second-guess all government regulatory decisions. In place of the enforcement of our laws as designed by Congress and the President, we will get further rule by judiciary. In other words, the Court’s decision effectively transfers power from devoted civil servants to ideological and unrepresentative judges.

Rosenblum’s assessment reflects my own concerns. The court upends a century of precedent and practice forged between the three branches, and replaces it with no practical alternative. The Court assumes that courts are more neutral and capable experts than civil servants with technical knowledge. They are not. They assume Congress, at a moment of historic unproductivity, will suddenly be able to produce extraordinarily detailed legislation that will guide federal agencies. They won’t.

One reason is capacity. Managing a big, modern society is complex, requiring lots of judgement. Judges are not subject matter experts, and do not have the technical expertise to become so. For example, Judge Gorsuch recently confused nitrous oxide (laughing gas) with nitrogen oxide (a smog-causing emission) in a decision to block an EPA rule. Even if they were, they are simply too few of them to become the managers of the administrative state. The SEC was already struggling to regulate fraud. Now, imagine that every crypto scammer with a lawyer can simply demand a full trial. The courts do not have the capacity to manage the scale of malfeasance, and so more of it will simply go unpunished.

Ian Millheiser wrote about this capacity challenge:

Loper Bright transfers a simply astonishing amount of policymaking authority from federal agencies that collectively employ tens of thousands of people, to a judiciary that lacks the personnel to evaluate the overwhelming array of policy questions that will now be decided by the courts. This problem will be felt most acutely by the Supreme Court itself, which has only nine justices staffed by a bare handful of law clerks and a skeletal administrative staff.

Kagan’s scathing dissent was grounded in the reality of governing, pushing back at the majority’s insistence that they were well-placed to run the country.

A rule of judicial humility gives way to a rule of judicial hubris. In recent years, this Court has too often taken for itself decision-making authority Congress assigned to agencies. The Court has substituted its own judgment on workplace health for that of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration; its own judgment on climate change for that of the Environmental Protection Agency; and its own judgment on student loans for that of the Department of Education…But evidently that was, for this Court, all too piecemeal. In one fell swoop, the majority today gives itself exclusive power over every open issue—no matter how expertise-driven or policy-laden—involving the meaning of regulatory law. As if it did not have enough on its plate, the majority turns itself into the country’s administrative czar.

Unelected bureaucrats does not mean unaccountable. Indeed, bureaucrats are so beholden to multiple types of accountabilities that they struggle to get anything done, and are often too cowed to try. They remain accountable to Congress. Even without legislative change, Congress directs agencies through leadership approvals, oversight hearings, the power of the purse, and formal and informal communications between committee and staff. By contrast, the Court can declare itself to be following Congressional intent, but with no meaningful check on that judgment beyond the court itself. Ultimately, who is the Federalist Society SCOTUS accountable to? Chiefly, to its private, conservative donors. As SCOTUS asserts a larger policymaking role, they wield more power but with less accountability than the administrative state they disdain.

Consider on particular form of accountability, which is who can receive money or gifts from private parties. Politicians can benefit from essentially unregulated money from those who might benefit from their decisions in the form of campaign donations and super-pacs. John McCain called the power of money in American politics “a system of legalized bribery and legalized extortion” before the Supreme Court opened the floodgates with Citizens United.

Judges appear to be in a similarly happy position, with the difference being they can personally enjoy the benefits of the money in the forms of forgivable loans or lavish vacations. Justice Thomas has benefited disproportionately from the network of money that opposed Chevron, receiving millions in gifts. The Court has determined that such behavior is fine, as long as it is reported, and really, even if it is not. The same week that Chevron fell, the court also upheld the right of a Republican Mayor to receive personal gifts from a trucking company to whom he had directed more than a million in contracts. The decision further eroded the capacity of prosecutors to pursue cases of corruption of public officials.

And what about those “unelected bureaucrats” — they cannot receive more than $20 in a gifts, or more than $50 from a single source in a year. If you are an organization committed to converting money into influence, federal employees are simply not available in the way that politicians and judges are.

As money gushed into every fissure of American governance, the exceptional insulation of the bureaucracy became a problem to be fixed. And now the Supreme Court has done so, undermining the potential for running a large, complex state based on nonpartisan expertise seeking to serve the public interest.

“Dobbs for the administrative state”

This was a Supreme court that was built to do two things: remove federal abortion protections and dismantle state capacity. It has done both.

Marci Harris, an expert on Congressional modernization, described the end of Chevron deference as “Dobbs for the administrative state.” And indeed, there are some real observations about some parallels between Dobbs and the attack on the administrative state. Neither are broadly popular, the result of some democratic demands. Despite the fact that both decisions speak to democratic imperatives - allowing state voters to decide in Dobbs, or returning power from bureaucrats to members of Congress - they have used unelected officials to frustrate popular will and previously constructed democratic means of governing. Members of the court increasingly shown themselves to be unmoored from traditional legal reasoning and practice, such as stare decisis, as they impose their Federalist Society theories on society. If conservatism means incremental change, nothing about this is conservative.

The capacity problem is real under normal circumstances, but in addition to moving more decisions away from the administrative bodies with the capacity to deal with them, the court has also expanded the zone of conflict, by inviting more lawsuits over past and future regulation. Well-resourced plaintiffs can use legal strategies such as venue-shopping, selecting a judge from their shared network who is guaranteed to rule with them, and impose a nationwide hold on the regulation.

In her dissent for Corner Post, Justice Jackson wrote:

Doctrines that were once settled are now unsettled, and claims that lacked merit a year ago are suddenly up for grabs…At the end of a momentous term, this much is clear: The tsunami of lawsuits against agencies that the Court’s holdings in this case and Loper Bright have authorized has the potential to devastate the functioning of the Federal Government.

Indeed. The Republican majority on the Supreme Court has unleashed regulatory chaos, diminished the state capacity needed to manage it, while transferring more and more decision authority to the judicial-political-corporate triumvirate whose interests will be protected at all costs.

As with Dobbs, I think we all knew they were going to do this but it's still shocking when it happens. Except for the Tax Court, most judges do not have the necessary subject matter expertise necessary to deal with what's going to happen. And, it's not going to happen overnight. It's the old frog in boiling water analogy. It'll start slow and then become overwhelming. When the Supreme Court issues harmful decisions the impacts are momentous and not in a good way.