The demise of academic freedom in Texas

Two cases in quick succession shows how politicization has broken Texas A&M

My first full-time faculty job was at Texas A&M University at College Station. I stayed just a couple of years, but have fond memories of the place. So its been disturbing to see the institution go through a couple of scandals in recent weeks that point to politicization of higher education at the expense of basic academic values. The politically connected and powerful are undermining the key levers by which public institutions can serve their students and the public more broadly.

Here is the latest scandal, as reported by the excellent Texas Tribune:

The daughter of a Texas politician, Texas Land Commissioner Dawn Buckingham, went to a lecture given by a clinical professor with expertise on opioids. Something that the lecturer said bothered the student. The professor was critical of Lt. Governor Dan Patrick. Patrick had been a colleague of her mom in the Texas Senate, and had endorsed her mom’s run for higher office. Her mom called Patrick. She also called the vice chancellor for governmental relations at A&M. Patrick was unhappy. He called the Chancellor of the Texas A&M System to explain his displeasure. He also called the chair of the University of Texas System’s board.

All of this happened very quickly. Within hours the faculty member, Joy Alonzo, had been publicly censured and put on leave, pending investigation. The Chancellor texted the Lt. Governor, saying “Joy Alonzo has been placed on administrative leave pending investigation re firing her. shud [sic] be finished by end of week.”

The politicization of higher education

The most telling fact in this narrative is that all of the people exercising power in this story are all politicians. Most obviously, Buckingham and Patrick. But also the Chancellor, John Sharp, and the Chair of the University of Texas System Board, Kevin Eltife. Both are former elected officials, Sharp a Democrat and Eltife a Republican, who have now become political appointees overseeing higher education. Eltife became chair of the Board of Regents after donating more than $150,000 to Governor Greg Abbott, who appointed him. The practice of political donations, rather than knowledge of higher education, paving the way for such positions of power is common in Texas and other states.

The Professor was ultimately not fired. But this came after a suspension and public censure without any due process. The chilling effects of the case are unmistakable. If you say something critical of the Lt. Governor in Texas, you can expect the leaders of the institution for which you work to try to fire you rather than reflexively defend your right to do your hob.

“DEI hysteria,” and a job offer rescinded

The second scandal resulted in the President of Texas A&M College Station, Katherine Banks, resigning.1 Banks faced questions from faculty about her role in a botched effort to hire Kathleen McElroy, a University of Texas-Austin professor, to come and lead A&M’s new journalism unit.

McElroy was hired with great fanfare. There was even a public signing ceremony, something that is a bit unusual for academics!

But what, exactly, was McElroy signing? She was originally offered a tenured position, appropriate for someone leading a school. Then, the offer was watered down to a five-year contract. Then the offer became a one-year untenured position, at which point McElroy withdrew.

What happened? Conservative alumni were upset at the hiring of McElroy and made their views known. What exactly was so objectionable about her? Right wing advocates in Texas labeled her a “DEI proponent.” The evidence for this was pretty thin, beyond a couple of comments that McElroy had made about the value of diversity. The chair of the department recruiting her was more blunt saying the objection was about race. McElroy, an A&M alum came to the same conclusion: “I’m being judged by race, maybe gender. And I don’t think other folks would face the same bars or challenges. And it seems that my being an Aggie, wanting to lead an Aggie program to what I thought would be prosperity, wasn’t enough.” She was the victim, she concluded, of “DEI hysteria.”

Regents paid a million dollar settlement after discriminating based on political beliefs

Behind the scenes, A&M University Board of Regents were signaling their own displeasure. A&M President Banks said she heard from six to seven regents about the hire. There are ten regents in total. One, Mike Hernandez, explicitly stated that “granting tenure to somebody with this background is going to be a difficult sell for many on the [board of regents],” and encouraged the university to “put the brakes on this, so we can all discuss this further.” He went on to state that the Board must “look at her résumé and her statements made an[d] opinion pieces and public interviews. The fact that McElroy had worked with the New York Times as a journalist made her suspect, since “The New York Times is one of the leading main stream media sources in our country. It is common knowledge that they are biased and progressive leaning. The same exact thing can be said about the university of Texas. Yet that is Dr. McElroy’s résumé in a nutshell.”

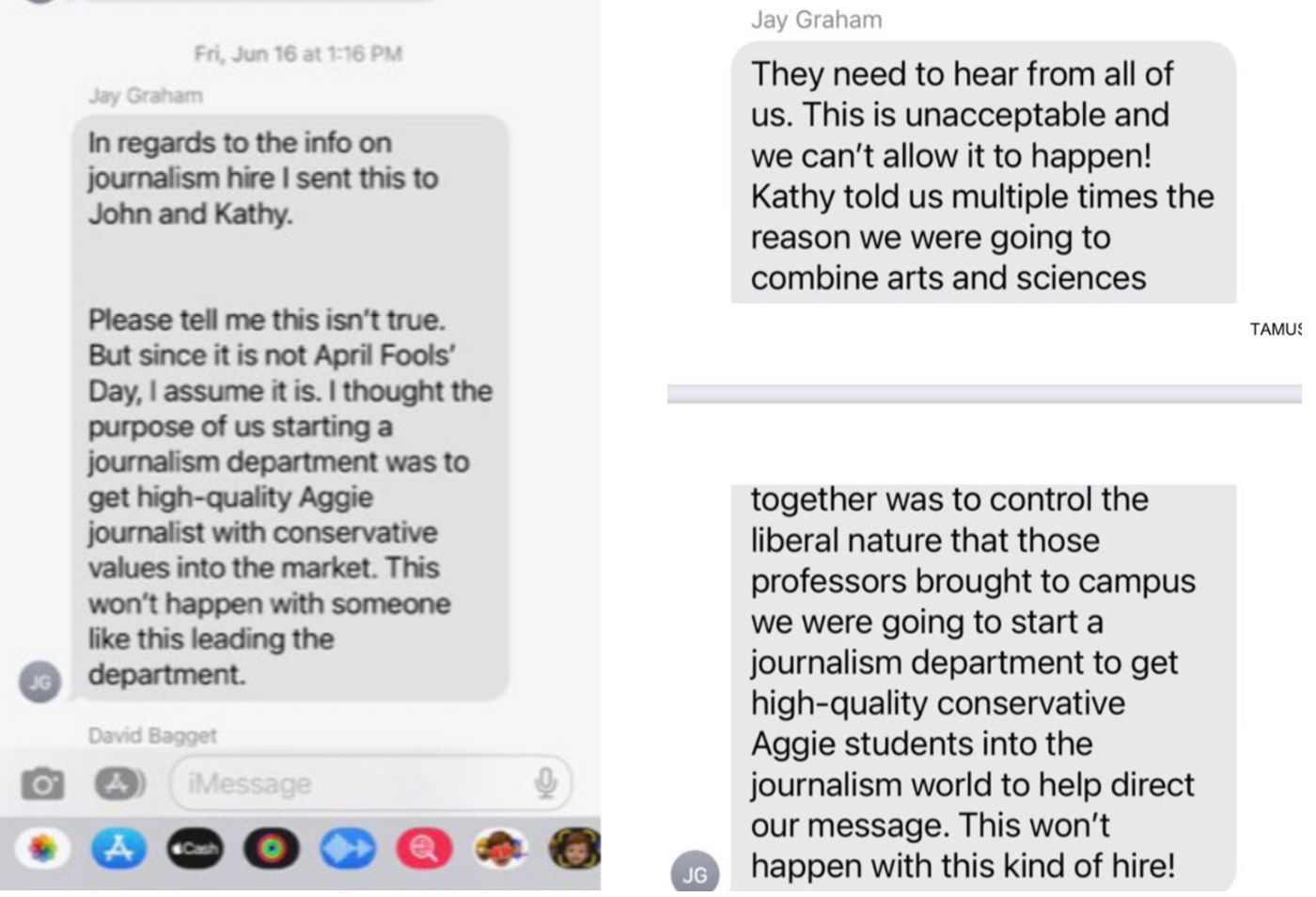

In texts with his fellow regent David Bagget, Jay Graham indicated that he told university leadership that he “thought the purpose of us starting a journalism department was to get high-quality Aggie journalist[s] with conservative values into the market.” He also indicated that A&M President “Kathy [Banks] told us multiple times the reason we were going to combine arts and sciences together was to control the liberal nature that those professors brought to campus. This won’t happen with this kind of hire.”

It is hard to overstate how extraordinary this all is on many levels. First, it helps to know a little about higher education to understand why. Regents are political appointees. They typically have no expertise in higher education. (Hernandez owns several car dealerships, Graham is the CEO of an energy company). They are also not a representative cross-section of Texas society. Instead, but are appointed because they are politically connected. One investigation found that two-thirds have donated to Governor Greg Abbott, who appoints them.

Even understanding that the Regents are partisan political appointees, here are four things that stand out as widely inappropriate in this case.

Regents have final say on tenure decisions. Given their lack of expertise, they typically defer to faculty recommendations, which are based on month-long review of research, and solicit outside letters from national experts. Tenure reviews come after a hire is made. But here, Regents signaled they would block a hire prior to any review, usurping a basic faculty role.

Regents very clearly did not use any defensible due process standards in evaluating McElroy, which is standard with faculty hires. No tenure file was assembled. Instead, the candidate was judged, negatively, for working at the New York Times, and at University of Texas-Austin, because they are perceived as liberal institutions. Right wing media sources mattered more than the candidate’s actual record.

The Regents also explicitly engaged in classic viewpoint discrimination: they opposed McElroy because they viewed her as liberal, and they wanted someone who would promote “conservative values.”

The Regents said they had been given reassurances by university leadership that major strategic decisions by the university — the creation of a new College of Arts and Sciences — “was to control the liberal nature that those professors brought to campus.” They view enforcing their preferred political views on the university as entirely legitimate, and expect university leadership to comply with this expectation.

Collectively, this reflects a broken culture of rampant political interference, where Regents do not feel obliged to follow university norms, rules or processes, or even the law, which prohibits discrimination based on political beliefs in hiring in public institutions.

What is clear is that McElroy was judged on her scholarly merits only when she was being recruited. That judgement was so positive that A&M wanted the world to know they had poached a prominent professor from their rivals at UT-Austin. Once the Regents got involved, her record of achievement did not matter. Her career, her value, was boiled down to some comments about the value of diversity. That was all they needed to know. That was enough for the university to renege on its offer.

Ultimately, the university settled with McElroy for $1M, and apologized. While initial reporting emphasized the role of “outside interference” by alumni it is clear that it was university officials, especially the Regents, that derailed the hire. The university lied to McElroy, first saying her hire was delayed for administrative reasons when the reality is that they did not want to announce it during the legislative session where legislators were making DEI illegal on state campuses. Then, the chair of the board of Regents, Bill Mahomes, wrote to McElroy to assure her that the Regents “did not discourage your hiring” despite the clear evidence that this occurred. The letter also said that that race and gender did not affect their hiring decisions. Maybe so, but McElroy’s perceived liberal beliefs and support for diversity and inclusion did clearly matter. Hence the $1 million settlement, which would have been unnecessary if it were just alumni complaining, but became unavoidable after a group of Regents who have fiduciary responsibilities to the university, but lacked any expertise in McElroy’s area, used their political biases to shape the hiring process.

Kafkaesque vagueness

Back to Joy Alonzo, the opioid expert. What did the professor actually do wrong? The public censure issues by the the university says it “does not support or condone these comments. We take these matters very seriously and wish to express our disapproval of the comment and apologize for harm it may have caused for members of our community. We hereby issue a formal censure of these statements and will take steps to ensure that such behavior does not happen in the future.”

This sounds very bad. But, oddly, it does not specify what the comments were. Based on the slides of her presentation, Alonzo seemed to have decried lack of resources devoted to fixing the opioid crisis in Texas, including:

how a lack of infrastructure limits the state’s ability to respond to the crisis, noting that many Texas counties lack a medical examiner; reporting on opioid deaths by emergency rooms is infrequent; and many law enforcement agencies and local health departments don’t track opioid deaths. This means the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considers Texas a nonreporter when it comes to opioid data, which makes it more difficult for researchers to receive grants to tackle the issue.

All of this seems like exactly the sort of thing that an expert on the topic should be talking about to students and to the public.

A pharmacy school dean mentioned in a memo to Alonzo that she had used “an anecdote and an interaction with a state official…I understand that your comment did not assign blame. However, some members of the audience felt that your anecdote was offensive.” Only one member of the audience, it seems, but the politically connected member of the audience matters, and their views and values matter more than the preferences of other students.

All of this makes it sound like Alonzo said something pretty outrageous. Buckingham would later claim in a tweet that Alonzo said: “Your Lt. Governor says those kids deserve to die.” Alonzo denies this. This seems like something so outrageous that other attendees would remember, but the university was unable to verify Buckingham’s claim. Other students at the talk were interviewed by journalists. None were offended. They did not know what any cause of offense might be. One suggested that Alonzo had said that Patrick had opposed policies that would have prevented deaths. The A&M investigation says that Alonzo “acknowledged that she had made a comment during her presentation about a meeting regarding the opioid crisis that occurred in 2015 or 2016.” You might consider this unprofessional, or an insight that seems something germane for the public to hear. But it is clearly covered by academic freedom.

Dan Patrick: Expect more of the same

Dan Patrick published a statement in the Houston Chronicle that not only defended his actions in calling the Chancellor about the faculty’s comments as appropriate, but warned faculty to expect more of the same in the future. Indeed, he argued, the real scandal, is that faculty were upset about him using his political power:

What follows is what bothers me the most. It is the ongoing outrage by the professors and their official “faculty senate” and, to some extent, the media. The A&M Faculty Senate has launched an investigation into, among other things, Texas A&M’s handling of Alonzo’s suspension. Their outrage seems based on the belief that anyone who dares ask a question about what is being taught or said in a classroom at a state university is somehow challenging their “academic freedom.”

The faculty senate is a real thing. No need for scare quotes! And they operate as a democratic body reflecting democratic values: a desire for due process, and transparency in the use of state power. Both of those things were lacking here, as Patrick well knows. He wasn’t just asking questions (unless the question was “can you punish this person who criticized me?”). He was using his exceptionally powerful position behind the scenes in a way that really did violate academic freedom. And what bothers him the most is that he was caught doing it, and that faculty, and to some extent the media, simply pointed this out.

This is what censorship looks like

Ultimately, this is not a close call. Unless faculty are calling for violence against someone, their speech is protected, and especially in a public institution where first amendment protections hold.

But the standard in A&M is quite different it seems. Unspecified comments that are offensive to some are all it takes. The vagueness feeds the chilling effect. Is any criticism of a public official for their policy actions out-of-bounds? What about the effects of abortion policies? Or immigration policy? Or a weakening infrastructure grid? Must faculty decorously elide questions of policy cause and effect to exclude the role of policymakers? If so, how are researchers whose work is related to public policy supposed to share their work with the public?

Faculty are left in a Kafkaesque situation, where they can be put on trial for unspecified utterances they supposedly made, without any real capacity to defend themselves.

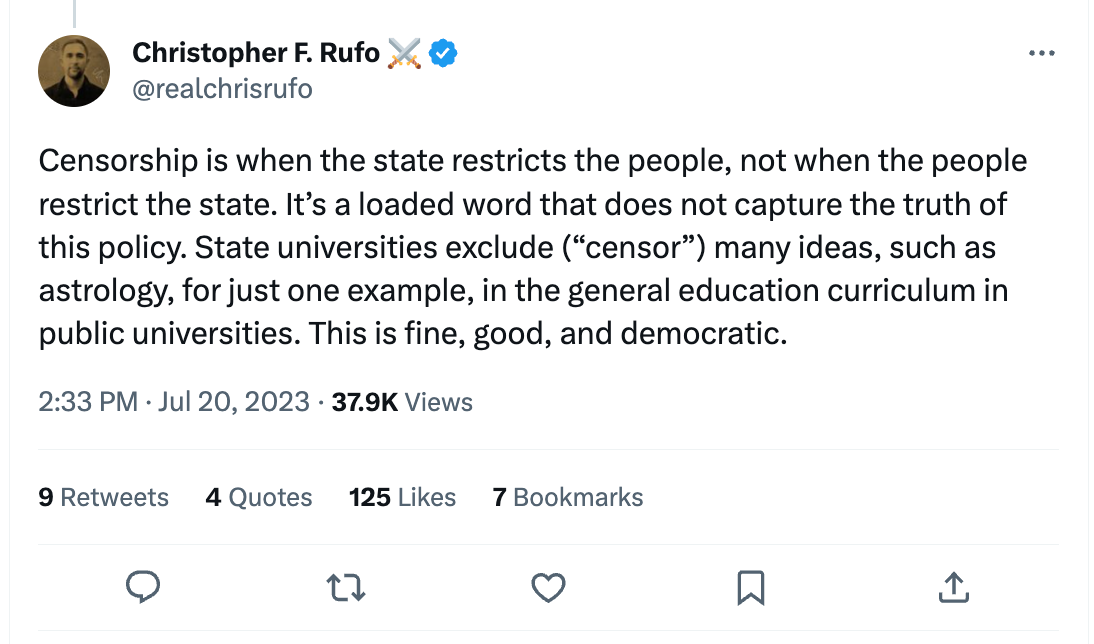

This is a scary proposition. The only speech that is allowed is politically approved speech. Censorship of such speech cannot be censorship, because the state is doing it.

The view of censorship advocate Chris Rufo sums up this point quite nicely. Censorship of faculty is fine, good and democratic, since they are not people. Rufo is a master propagandist, at least if you never stop for a moment to think through the Orwellian logic he is persuading politicians to adopt. For example, Rufo’s views are not meaningfully different from the state of Florida, whose lawyers have argued in court that faculty have no right to hold a view contrary to state positions, and they can be fired for expressing such contrary views.

Why have faculty with research or critical thinking skills, if their job is merely to uncritically parrot the pronouncements of the regime?

This isn’t just about faculty

It is not just faculty who are affected here. It is also students, and the public who depend upon academic expertise in domains like public health. Those who want frank discussions of what policy and policy implementation looks like in their state cannot be confident they will get it from a cowed faculty. Student education is shortchanged as a result. The only thing students can learn from a state apparatchik is how to conform to the regime. While none of the students interviewed by Texas Tribune reporters found Alonzo’s talk offensive, none wanted to go on the record “for fear of retaliation.” They are learning already how education and power works in Texas.

Incompetent and corrupt politicians are especially unwilling to accept both criticisms and the academic independence that enables it. This is why authoritarians routinely target academics and academic freedom. It is why Dan Patrick proposed stripping faculty of tenure protections last year. Patrick lost, because academic leaders told policymakers it would be impossible to recruit and retain faculty without tenure. But Patrick’s actions will send much the same message to current and prospective faculty.

If I was asked by someone contemplating a job at Texas A&M today about going there, I would explain the positives, but also suggest that if they want to have any capacity to speak to the public paying their salary, they may want to look elsewhere.

Texas has a great higher education system; for how much longer?

One thing I marveled about while living in Texas is that despite the very conservative nature of the state, there was real support for investing in state higher education institutions. Key policymakers tended to be alum, and there was a justified sense of pride in the contributions of public institutions offered to the state.

But that was a different era. Now key policymakers have persuaded themselves that higher education is the enemy, something that must be controlled, and if necessary, broken. Generations of people built these institutions, but they are being taken apart by today’s culture war zealots.

A core job of being an academic leader is to shield faculty from political potshots. But they face increasing pressure from political zealots, or are zealots themselves. The blurring of academic leadership with a political class at war with academic values has real costs.

Alumni should not be part of hiring processes. Job offers, once made, cannot be modified to suit the political powers-that-be. Politicians should not be able to punish an individual faculty member for speaking their mind. Academic leaders have to be able to tell those politicians, “like it or not, they have the right to say what they want.” In states like Texas, this is no longer happening.

Everyone involved knows this. Chancellor Sharp was happy to criticize outsider interference in the McElroy hiring scandal, saying it was “never welcome, nor invited.” Those were the right words, but when it came down to it he was perfectly willing to bend to outsider pressure when the Lt. Governor called. He staked his colors to the mast, which were pleasing his political masters at the expense of defending the most basic academic values.

Lets not excuse the participants. The first year medical student decided it was her job to tattle on a Professor. Politicians are used to receiving harsh criticism, but if they can punish the critics, they will, even if it means undermining the institutions they are charged with upholding. They shared a sense of political entitlement. Their feelings mattered more than anything else, and their political power was all that was needed to remedy the problem.

This, ultimately, is what is common across the two cases. A group of powerful political actors wanted to impose their political values onto what faculty are hired and what they are allowed to say. In both cases, they succeeded. They succeeded despite the fact that their actions were illegal or inappropriate, and clearly undermined foundational values that a university is based on. They will receive no punishment for this. They acted as if it is normal, because it probably is normal for them. But they are upset merely that their actions were exposed in a way that discomforts their certainty that the rules do not apply to them. (After the similar fiasco with the tenure denial of of Nikole Hannah-Jones at University of North Carolina, you would have thought that right-wing regents determined to go after progressive academics would have figured out not to target journalism professors who understand how media works).

Who are teaching the actual forbidden courses in America?

A while back Bari Weiss declared she was setting up a university - in Texas - to fight campus censoriousness. She got a lot of free media for this claim. See the headline below from the New York Times for example.

The Potemkin university promised a whole series of “forbidden courses” where its faculty could cosplay as brave truth tellers.

But who are teaching the actual “forbidden courses” in America? It is faculty in public institutions, who teach about the relationship between race, gender and power. It is faculty who are willing to criticize poor public policy. These are the ones likely to be punished for their statements, by state actors.

Much of the media, especially the national media, has completely botched this basic point over last decade, as I’ve mentioned numerous times before (see also this piece by Thomas Zimmer). The have pushed the idea that wokeness represents the greatest threat to our freedoms, and in doing so empowered actual censors like Dan Patrick or Ron DeSantis. It is, and always has been, thin-skinned government actors determined to shut down anyone willing to speak truth to power that we should be most wary of. The people who still cannot see this simply do not want to.

This post, originally made on July 25, 2023 was updated on August 4th to reflect the results of an internal Texas A&M investigation into the two cases.

This is a bit confusing, but there is Texas A&M System, with multiple campuses, of which Texas A&M College Station is the largest. The System is led by Chancellor John Sharp, a former politician, while College Station was led by President Katherine Banks, and engineering professor.

I'm a retired academic (PhD University of Houston, accounting), taught federal taxation mostly at the graduate level (more than 35 years) and was also an associate dean of a business school for more than 25 yrs. This type of behavior could affect any discipline as they are all linked, in one manner or another, to government policies. Business faculty frequently talk about laws, regulations and. policies including their personal opinions in these discussions. While tenured faculty should be alright, this behavior could also affect promotions, committee assignments, grants, teaching schedules, office space, and as you said, most definitely research. Any faculty in a discipline where demand exceeds supply will consider staying away from Texas and Florida and other Republican led states and this will affect those schools/colleges/universities for a long time. This is beyond hypocrisy, it's ignorance.