Strongman, Weak State

The dispiriting vision of American governance offered by the Roberts Court

The hinges of history, the moments that determine the shape of our world, are usually only obvious in retrospect. Sometimes, dramatic political events, like assassinations, announce their own importance. The last week of Supreme Court decisions manage to be both obviously and profoundly dangerous, and also overlooked. While they have garnered coverage, that coverage has been secondary to speculation about President Biden’s future.

The front page of the Times is not an exception. One the one hand, a casual consumer of the media would gain little sense of the momentous changes that have been paid out by the Roberts court at the end of its term. On the other hand, if you pay reasonably close attention to politics and government, the decision on Presidential immunity beggars belief, with long-term implications that can scarcely be imagined. As an example, Quinta Jurecic, a Brookings Institution expert on law and democracy, and contributor to The Atlantic said on BlueSky: “I really cannot emphasize how catastrophically bad the Court's ruling was. I do my best not to exaggerate about these kinds of things but I am still kind of in shock.”

Donald Trump, a profoundly corrupt individual, twice impeached, demanded that the Supreme Court provide him immunity protection for his misdeeds. Despite the obvious threat posed by a man favored to retake the Presidency while attacking democratic processes and promising retribution to his political opponents, the Republican majority granted his demand.

More specifically, Chief Justice John Roberts offers the President absolute immunity from criminal prosecution in official conduct. The President gains “presumptive immunity” in other cases. The decision offers Presidents broad cover. As long as they say their actions were “official conduct” investigations cannot question the President’s motives. Trump calling election officials or state legislators to pressure them to overturn election? Surely, the President can investigate election as part of his official conduct. Soliciting bribes for pardons? Offering bribes to foreign leaders for dirt on his political opponents? Official conduct. These are real allegations made against Trump, now washed away under the banner of official conduct. The court offers no test about what differentiates “official” from “unofficial” acts, also forbids the use of evidence related to his official acts for other crimes.

Writing the dissent, Justice Sotomayor offered an even starker, but plausible, parade of horribles:

When he uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he now will be insulated from criminal prosecution. Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune.

Some legal scholars presented a tension between Trump’s threats to violate the law and the threat that “responsible presidents by the specter of after-office criminal judgment.” One of these threats is a clear and present danger to democracy, and the other one is not. How frequently in American history have American Presidents been subject to excessive punishment for bad behavior? You can make a strong case, instead, that the tendency to forgive men in high office for their crimes has encouraged such behavior.

Trump, the first presidential felon, is only a partial exception. His impeachment for fomenting an insurrection was derailed by Mitch McConnell and other Republican Senators who insisted that the legal system would hold him accountable: “We have a criminal justice system in this country. We have civil litigation. And former presidents are not immune from being held accountable by either one.” Almost four years on, the legal system has failed to hold Trump accountable, and will not before he would gain authority to pardon himself. The only convictions has been for actions undertaken back in 2016, before he was President.

We live in an era where novel or an obscure legal theories have become part of our constitutional jurisprudence. Nonetheless, the idea that a President was above the law seemed like the longest of long shots. At the time Trump’s lawyers brought the case, it seemed so obviously ridiculous that the court was criticized as engaged in an attempt to delay, rather than prevent, the reckoning of Trump’s legal liabilities by hearing it. Rejecting Trump’s claims, the DC Circuit noted that they were “unsupported by precedent, history or the text and structure of the Constitution…Former President Trump's stance would collapse our system of separated powers by placing the President beyond the reach of all three Branches.”

The Supreme Court Judges that granted the President protection from the law not afforded to any other citizen insisted to the Senate under oath that the President was not above the law. From their confirmation hearings:

Alito: “no person in this country is above the law, and that includes the president”

Kavanaugh: “No one is above the law. And that is just such a foundational principle of the Constitution and equal justice under law.”

Gorsuch: “No man is above the law. No man.”

Roberts: “I believe that no one is above the law under our system, and that includes the president.”

Barrett: “No man is above the law.”

These were not idle questions. Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett were confirmed amidst a backdrop of questions of about whether Trump had violated the constitution, via, for example, the Emoluments Clause. Alito and Roberts were questioned amidst criticism about the excesses of George W. Bush’s 9/11 authorities, including allowing torture. It was not just confirmation hearings. As late as 2020, Clarence Thomas wrote: “The text of the Constitution … does not afford the President absolute immunity.” But in 2024 he declared that the executive demanded such immunity. I don’t think any reasonable person would believe this court would have made the decision if a Democratic President was the one that had asked the majority to change their mind.

A previous generation of the Supreme Court had rejected such an extravagant claim of Presidential immunity when Nixon advanced them amidst Watergate in 1974. Fifty years later, the Roberts court more or less embraced Nixon’s constitutional theory that “if the President does it, it’s legal.” According to Nixon aide John Dean, “the new ruling, in effect, decriminalizes Nixon’s conduct during the Watergate scandal.”

A court built on principles of “originalism” and “textualism” could not discern that the plain text of 14 Amendment prohibited an insurrectionist from retaking the presidency. They could not find that the emoluments clause had any constraining effect. And yet they imagined into the constitution that the founders were friendly to a criminal executive.

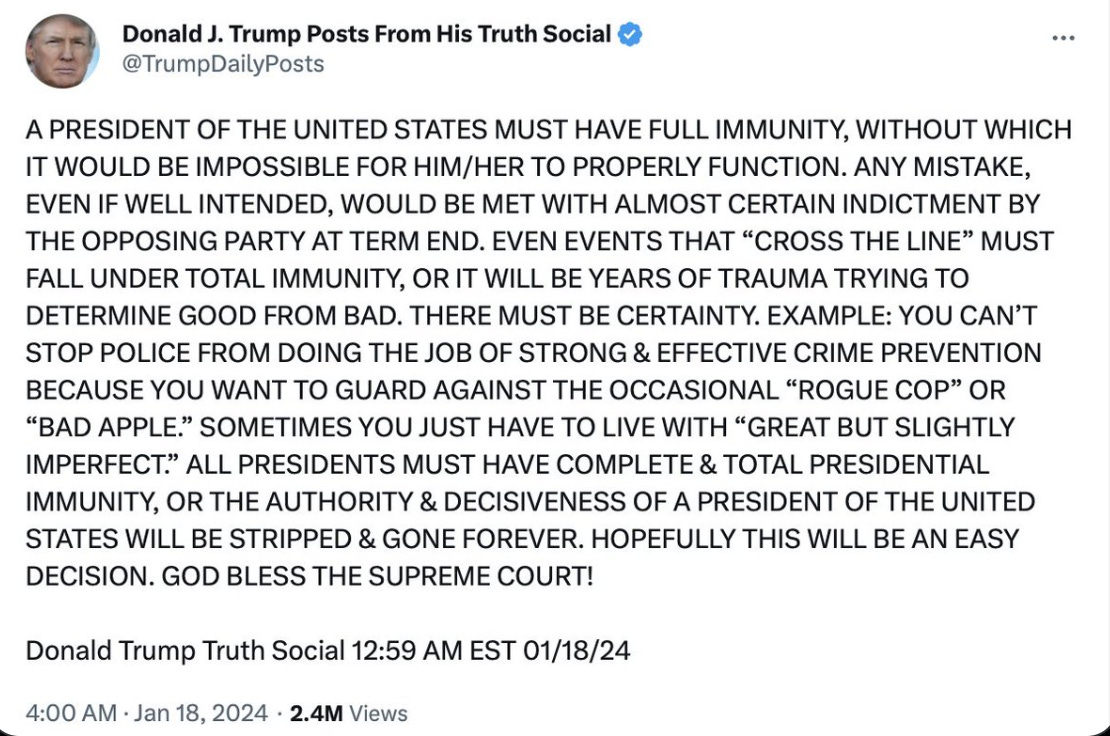

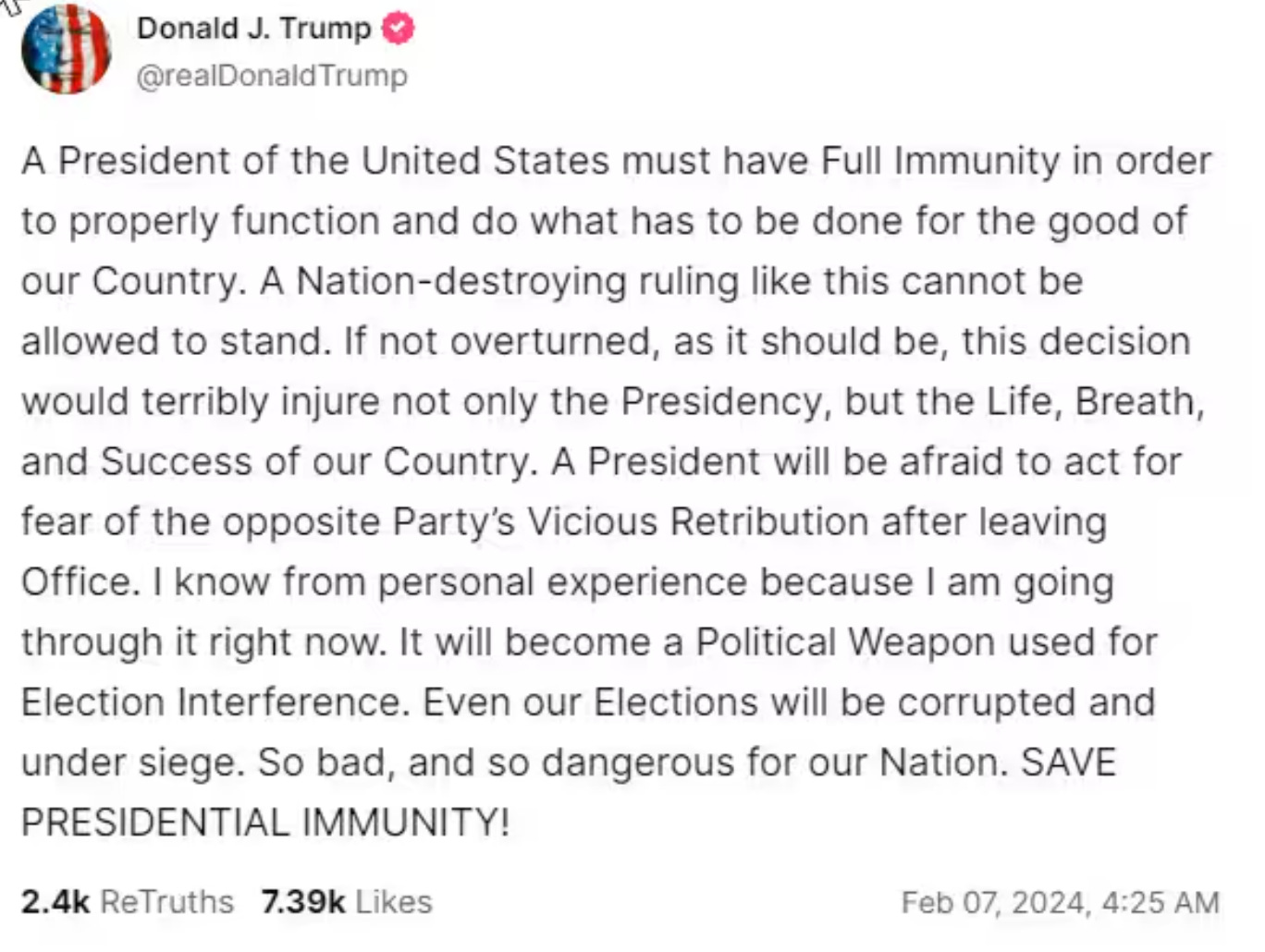

The fact that the founders, who built a revolution based on a series of complaints against a lawless executive, specifically refused to offer the President immunity for prosecution, mattered little. If the Roberts court could not find textual justification from the founders for their decision, they did find it in Trump’s speeches and social media:

These are the texts driving the court’s textualism, an originalism that dates all the way back to Donald Trump’s demand that the court bail him out of the consequences of his misdeeds.

The Court’s claim of the majority that “the energy of the executive” demands such immunity is put to the lie by their own actions. Days before acceding to Trump’s demands, the court released a series of decisions, most obviously Loper-Bright, that significantly weakened the executive, removing power from state actors as part of a long-sought goal of dismantling the administrative state. In the space of a week, the court reshaped American governance, prioritizing corporate power over the ability of the state to regulate, and prioritizing presidential power over the rule of law.

In their decisions, we can discern the future of American governance: strongman, weak state. The president is free to do bad, the state itself as a collective expression of the public interest must be constrained from doing good. The dangers of the court’s ever growing willingness to boil the executive branch down to the person of the President, when the person most likely to be President is obviously corrupt, has never been clearer. In the view of the Robert’s court, we do not have an executive branch; we have the President. If you think this is exaggerated, read Robert’s opinion: “unlike anyone else, the President is a branch of government, and the Constitution vests in him sweeping powers and duties.”

This is the unitary executive theory that will fuel the excesses of a Trump second term. For example, Trump and Project 2025 has argued that the idea of Department of Justice independence is a myth, that the President should be free to shape DOJ investigations. The implication is the President can redirect DOJ investigations away from himself, and towards his political enemies. It is a claim that Trump DOJ official Jeffery Clark has made, even as he was indicted with Trump for abusing their offices as part of a scheme overturn the election results in Georgia. In an aside in the decision, the majority appeared to grant the Presidential control over DOJ that Trump has sought: “The President may discuss potential investigations and prosecutions with his Attorney General and other Justice Department officials to carry out his constitutional duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”” Similarly, Roberts took pains to make clear that Trump’s pressuring Mike Pence to reverse the election outcome is likely protected.

Sometimes societies make bad decisions with the best of intentions, or under the influence of an inspiring figure. But the Supreme Court has done all of this for Donald Trump. They offered him immunity for his crimes, past and future, amidst his pledges to abuse state power to prosecute his enemies. The court has handed a constitutional arsonist a box of matches and a can of kerosene. The consequences are entirely predictable. It is the most degrading and unnecessary surrender of American sovereignty.

Hyperbole is a temptation. But I cannot recall a more shocking decision from the Roberts court than this one. The destruction of the administrative state via Loper-Bright, the end of abortion rights via Dobbs, the gutting of the Voting Rights Act via Shelby, and the embrace of money in Citizens United. All were appalling and destructive in their own ways. They were also, to varying degrees, expected, consistent with a perverse logic, with predictable enough in their outcomes. The Trump immunity decision defies all such logic. It makes sense only if the court believes that Trump’s promised retribution is their retribution. And it opens a Pandora’s Box of corruption and abuse of the Presidential office in ways we can scarcely imagine.

Once I was walking by the Supreme Court building and happened to notice the inscription; "Equal Justice Under Law." I'm such a Yankee-doodle softie, that I actually misted up a little. We'll probably never get there, but striving to provide equal justice to all is a very noble goal.

I'm afraid that when Roberts and crew look at the inscription, they're wondering how a new inscription would look. Something along the lines of "There must be some the law protects, but does not bind, and some the law binds, but does not protect."

Since Citizens United, through Dobbs and immunity, the Supreme Court has been paving the way for an easy implementation of Project 2025. It's past time to expand the Supreme Court. Both abortion and now the Supreme Court have become kryptonite for Republicans, and their arrogance and hubris will backfire on them.