Sneak preview: The Biden student loan forgiveness process is good!

The Department of Education designed a low-burden process that will maximize take-up

We are starting to see details about the application process for student loan forgiveness. [Update: The website with the application is now live as of Oct 17th]. This is the sort of stuff I obsess about, so whats the verdict?

The proposed student loan forgiveness process is well-designed, given constraints, and bears all the hallmarks of a presidential administration paying careful attention to administrative burdens.

Earlier this year I suggested that the effort to forgive student loans could be the “new Obamacare website”: a massive implementation own-goal. I am happy to report that I now expect that my concerns were misplaced (or more self-servingly, to claim that the White House was paying attention to my concerns!). Indeed, based on early communications, the White House will be touting the simplicity of the process as a key feature.

Much of my initial skepticism was centered on three factors:

The Biden administration made loan forgiveness means-tested, meaning that the Department of Education would have to sort out who was eligible and who was not based on income, making the process more onerous.

The Department of Education could not automate income-verification checks because of legal constraints on the use of IRS data. Which is sort of nuts when you think about it.

The Department of Education has a bad track record on student loan forgiveness programs when they have been unable to automate the process, though the Biden administration has improved many of these processes.

So why I am feeling more optimistic now?

What the application process looks like

Using administrative data where possible

The Department of Education is using administrative data where legally possible. In particular, it will use income data from non-IRS sources for about 20% of the 40 million beneficiaries to automatically erase their debt without an application process. It also has data on which users are Pell grant recipients, and so does not require documentation for those seeking to claim the $20K debt forgiveness.

An application process with minimal burdens

The White House has provided enough details about the online application process that we have a good sense of how it will work.

It is simple, available both for both mobile phones and computer, in English and Spanish.

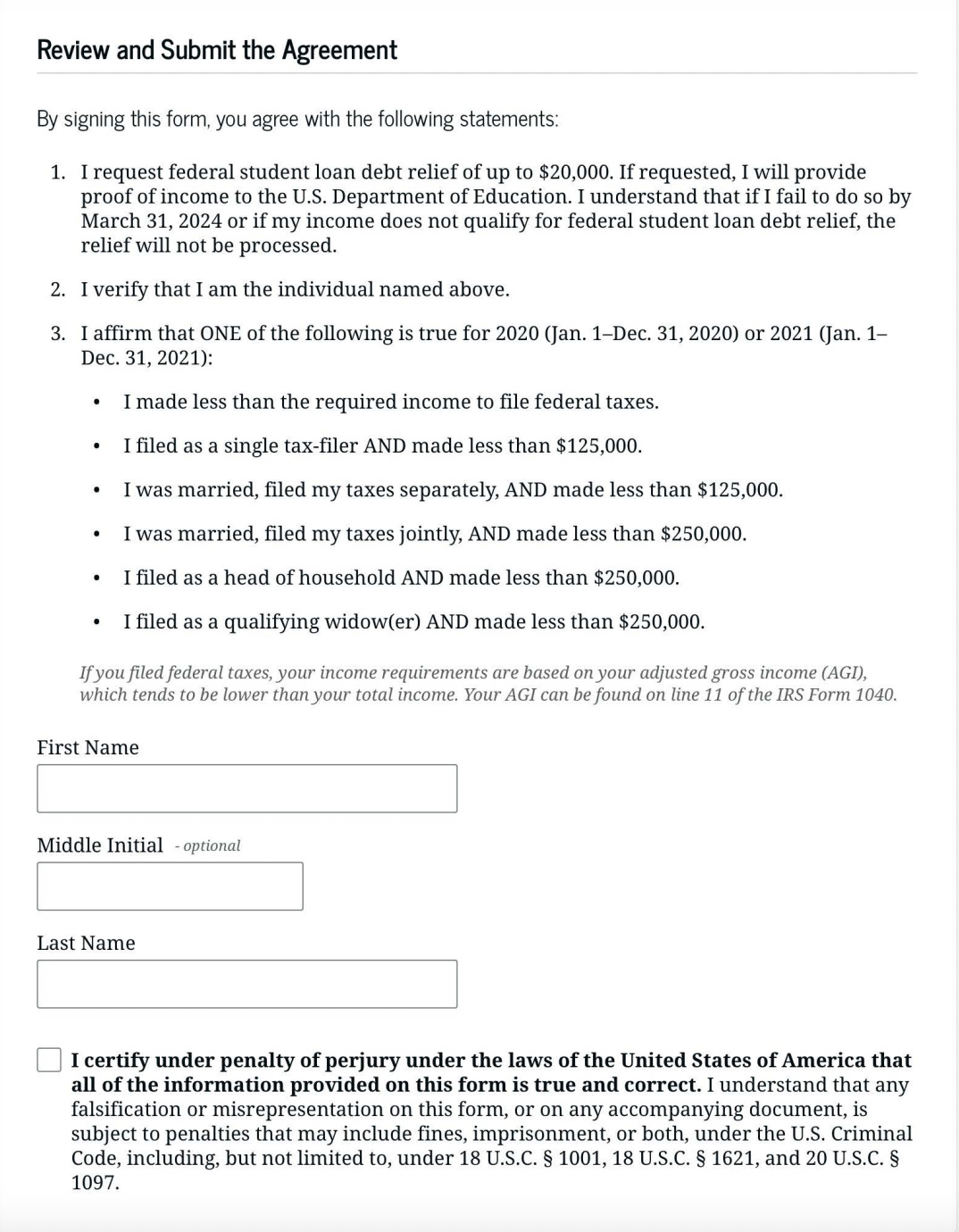

Here is what the application process will actually look like (hat tip to Politico education reporter Michael Stratford).

Simple intro:

Borrowers will need to provide 1) name, 2) Social Security Number, 3) date of birth and 4) phone number and 5) email.

Borrowers then declare that the information they have provided is accurate, on penalty of perjury.

Thats it!

This is a well-designed form! It looks good, does not ask for too much information, or information that individuals cannot easily remember. Users do not have to set up a user ID or password, or log into another website, other small but significant barriers.

Here are some other things that are good about the process.

Shifting burdens onto the state

Borrowers do not have to interact with private lenders, but only with the Department of Education, creating one-stop-shopping, and less room for confusion or miscommunication. This is a massive improvement in student loan processes that requires beneficiaries to jump back and forth between multiple actors. That work is left to the Department of Education. This follows a simple rule of burden reduction: shift burdens onto the state where possible.

Using self-attestation rather than documentation

A positive aspect of the design is minimizing the need for documentation, including the Federal Student Aid ID information. Instead, as I proposed in May, the Department of Education is using self-attestation, i.e. people will simply promise that they are telling the truth.

Self-attestation is a great tool to cut through bureaucracy, but it does create some risks. What if people are lying? For this particular benefit, the risks are low. The number of people who are over the income limit is small, meaning the pool of potential beneficiaries from fraud is also small. The government is not sending out money here, rather, it is reducing loan balances. This means there is little risk of criminal fraud. The only people who can gain a benefit are those who have student debt. And, the government can easily track anyone who engages with fraud and hold them accountable via a back-end audit process.

The effect of self-attestation will, I believe, be enormous. It exempts borrowers from collecting and submitting documentation that has stymied other loan forgiveness programs.

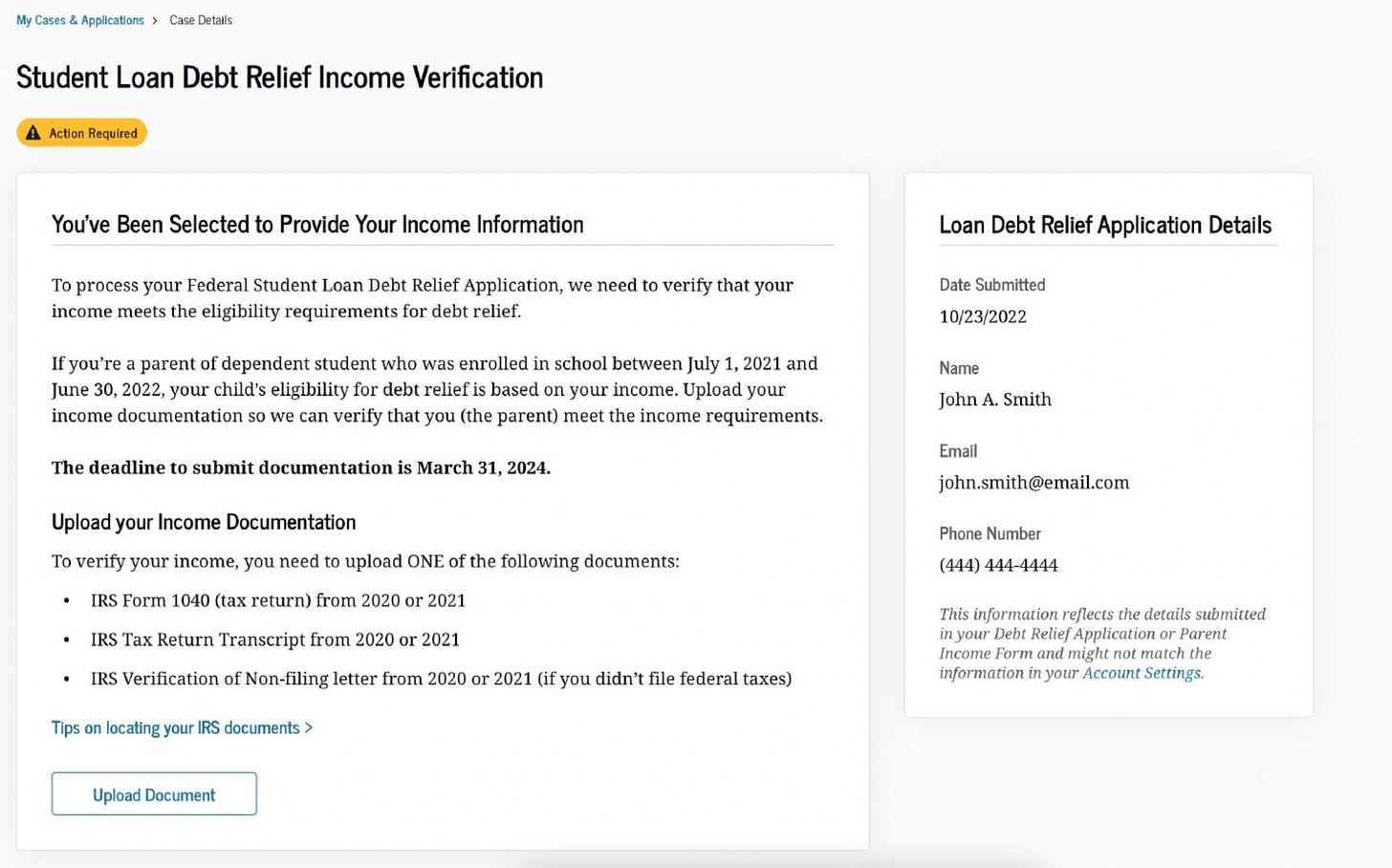

Initial reports are saying that the Department of Education will flag 1-5 million borrowers to provide extra verification before it processes their student loan forgiveness.

This would require accessing a prior year tax return and uploading it, and creating a login to provide this information. Not nothing, and could stymie some eligible beneficiaries, but also fairly feasible for most.

Where are the potential pain points?

People are much more likely to engage in routine processes that are familiar to them. Student loan forgiveness is a one-off, so there are learning costs that will depress take-up.

There are a few other reasons that might lower participation. One is that there are scammers out there, and people are wary. The barrage of lawsuits (and potential of delays because of them) may create confusion about the program.

The non-universal nature of the program means that some might be confused about their eligibility. Will people understand the difference between gross income and adjusted gross income? Then again, the cut-off is so high ($125K for an individual) that these will generally be people who are aware of their income and have easy access to tax returns.

Finally, the self-attestation comes with an acknowledgement that you are not lying and are subjecting yourself to a potential audit and legal liability. This feels like an inevitable requirement to minimize up-front documentation processes, but some might be scared off by the legalistic language.

There is always the risk of unknown pain points that don’t reveal themselves until a system is up and running. There may be problems in the back-end of converting the applications to forgiveness. And some people may never get to the website in the first place. This is the problem with administrative burdens. You can draw from past experience but still not predict all problems. But that prior experience does inform my belief that once people once get to the website, they should have a smooth experience.

A big unknown: The power of social persuasion

In the same way that elections are partly social events, where people are swept up by social networks to act, I think signing-up for loan forgiveness will occur in a context where the benefit will be widely discussed, and people will be embedded in networks that will encourage them to participate. The deadline for submission will be December of 2023, so there is a long period of time to reach and tinker with messages to motivate the hard-to-reach.1

The federal government will have its own outreach efforts, but community groups seeking to help their members will play perhaps a more important role. Student loan forgiveness comes at the end of a multi-year movement, where members of that movement have strong normative desire to help others to benefit.

This social effect also means that I don’t think there will be stigma or other types of psychological costs that might discourage you from spending time in the welfare office. People will want to join the party.

How well will the process work?

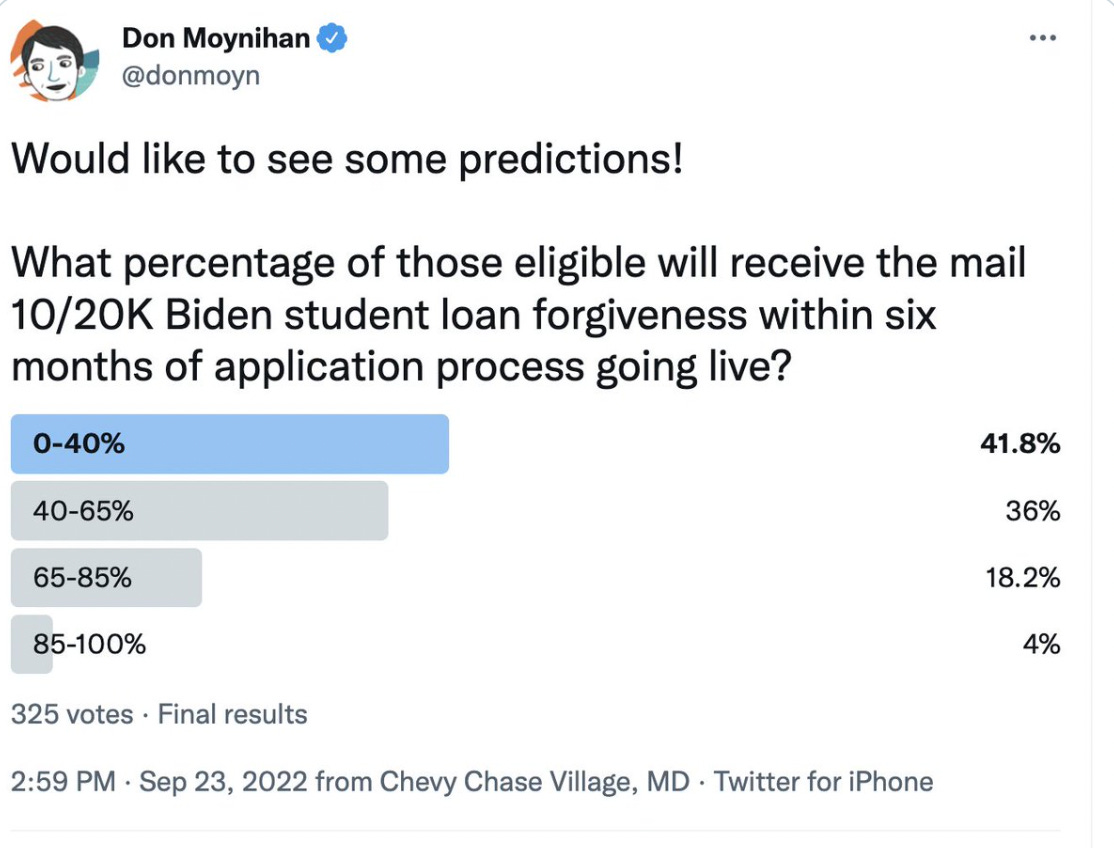

An entirely unscientific poll of my followers a few weeks back proved skeptical about the outcome of the application process in terms of take-up.

You might think: the $10K/20K on offer is a huge benefit. Who would not sign up for that? The short answer is that there is large variance in take-up of valuable benefits because, in no small part, of the learning, compliance and psychological costs that come with administrative burdens.

The Earned Income Tax Credit has one of the highest take-up rates of about 80%. But this still means that for a process that has relatively low burdens, occurs every year, and where people benefit from the professional help of tax preparers, about 1 in 5 who are eligible leave thousands of dollars on the table.

Maybe the closest comparison is selection into pension systems, where an individual has a strong financial incentive to complete a one-off application form. When the UK moved to change the default of such processes to be an opt-out rather than opt-in, take-up increased from about 61% to 83%. One implication is that that even simple opt-ins can be costly. Another is that some people will deliberately opt out of a process that, on paper, appears beneficial to them

Prediction

It’s quite hard to estimate what the take-up rate for student loan forgiveness because it is a unique benefit. In estimating the costs of student loan forgiveness, a bunch of economists at the Congressional Budget Office and the White House/Department of Education give their best guess as to take up. They are both fairly optimistic. CBO predicted a 90% take-up rate, while the White House proposed it would be 75%.

I don’t think anyone truly knows the answer given how unique the program is. In other words, both figures could be viewed as defensible, but both assume there will not be something like the Affordable Care Act website implementation failure.

All that said, there is my prediction:

80% of those eligible will receive student loan forgiveness.

I would like to be even more optimistic, but I would regard this as a success, certainly compared to my initial expectations and the record of previous student loan forgiveness programs.

It is also another example of the Biden administration being attentive to administrative burdens, and working to minimize them where possible. This does not mean other considerations disappear, like the politics of making it means-tested, but we should be grateful to have an administration that invests in making sure key citizen-state interactions work.

f you found this post useful, please check out the archive, consider subscribing, and share with others!

In the first version of this piece, I incorrectly implied that the deadline was December of this year.