Hello from the other side of COVID

Postcard from Denmark, where an entire country decided all at once that COVID was over

“One day everyone was wearing masks, and the next day no-one was.”

The COVID pandemic is over in Denmark. At least that is what it feels like. Since February 1st, there are no restrictions on bars and restaurants. It is no longer considered a “socially critical disease.” The most visible signifier of the pandemic, the facemask, has almost completely disappeared from everyday life.

Copenhagen’s most famous resident has moved on from COVID

It fascinated me that health-protective behaviors that were widely accepted and conformed with when the government required them were so immediately and universally abandoned when the restrictions ended. It struck me that such a collective change is not possible in the US, and that this difference says something about our countries and their capacity to govern. I was so curious I went to Denmark to better understand what was happening.1

What would it feel like if your entire community decided today that COVID was over? Some of you might say that that has already happened in parts of the US. But we are so polarized that our policies and daily interactions around COVID come with disagreements and resentments, minor acts of rebellion or resistance. What I mean is, what if *everyone* really agreed, it’s over, time to move on?

Consensus seems beyond us in the US. Thus, there is not going to be a single, agreed-upon point where we collectively agree that it’s over. Instead, COVID will have a long and contested goodbye, all the more so because COVID does not actually appear to be likely to ever really go away.

My observations comes with all sorts of caveats. I am not going to make any judgment about the wisdom of Danish health policies. Other countries have prematurely declared the pandemic to be over. Think about Boris Johnson spending the UK’s “Freedom Day” in isolation. My interest is more in how people understand the change in restrictions.

I talked to maybe 20 people on the topic, and could not find a single person who believed the restrictions had been lifted too early.2 Not only were the policies widely supported. If the virus took a negative turn, people believe the country would collectively bear the return of public health restrictions.

Normal — or a new normal — rather than freedom as the goal

I’m not going to pretend to be an expert in this travelogue-as-news stuff. But I know enough from the master of the craft, Tom Friedman, that the heart of the piece has to center on my conversation with my taxi driver.

My taxi driver wore no mask, as I did, during our 40 minute ride from Billund to Aarhus, and did not inquire about my comfort with her choice. As we approached my destination she observed, gently, that restrictions had been lifted here in almost all places except hospitals and airports. Maybe I was unaware of this!

So we chatted about it, and I asked her thoughts. The first thing she noted is Denmark’s high vaccination rate. And so many people had gotten the Omicron that there was herd immunity. Business was improving again. She was barely seeing her kids, who were catching up on two years of lost time hanging out with friends.

In the US we talk about freedom a lot when it comes to health restrictions. In Denmark people talked more about “normal” — or “almost normal” — much more. At some level, even relatively minor health restrictions feel intrusive because they remind us that something is wrong.

Like my taxi driver, the Danes I spoke to almost always brought up the high vaccine rates. It was a point of pride. The role of the state could be less intrusive precisely because the guidance of the state was more accepted. For the same reason, vaccination mandates were unnecessary.

People also felt that the Omicron wave had made the disease more or less endemic. “We’ve been triple-vaxxed and most people have had it” said one student. A solid majority of the people I spoke to had gotten COVID. In some ways, it provided a sense of relief. They had encountered the worst, and moved on. They didn’t seemed concerned about the risk of long COVID.

I stayed mostly in the the college town of Aarhus. On Friday night on campus, I joined a group of about 50 people eating and drinking to celebrate a dissertation defense. Walking home, I passed masses of undergraduates partying in the college cafeteria, and long lines at the nightclubs. Not a mask to be seen.

Photo credit: Me, walking past, but not actually going inside the cafeteria-turned-nightclub on the college campus

The “normal” they spoke about was different than before. It was a normal that assumed COVID was endemic and something you might catch sooner or later, but those risks were not enough to justify significantly altering behavior any longer.

More trust, less conflict

The restoration of normality seemed to hinge explicitly on trust in government. One professor of political science joked that maybe the Danes are too obedient, too trusting. But he also pointed to the benefit of such trust. COVID causes conflict about what is the right set of policies at any given time. If everyone agrees to defer to the policies of the government, even if they don’t always agree with those policies, this removes that source of conflict from the interpersonal sphere. We don’t face a daily negotiation with friends, work colleagues, or random people on public transport or the grocery store about what is the appropriate standard. We go along with the policy, we trust the government, we fight less.

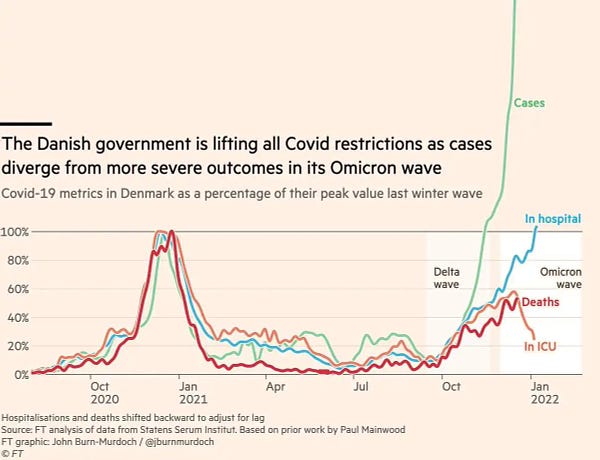

Danes frequently brought up how their relaxing of health restrictions were perceived by Americans. This is, I think, partly a function of being in a small country. Having grown up in Ireland, I noticed we were intensely curious about how others perceived us in a way that Americans are not. Some I spoke with felt a little stung by criticism thrown their way, especially those they perceived to ideological allies. Why was a good liberal like Paul Krugman judging them? They brought up the fact that climbing infection rates were not resulting in greater mortality, and when I pressed on this, made the distinction between deaths with and deaths from COVID.3 Did people not understand the statistics? Denmark was not America. Why were Americans viewing Denmark through their culture-war prism?

How it felt to be the one guy wearing a mask

My own behavior changed from setting to setting during my short stay. With smaller groups I did not wear a mask (for example when I gave a seminar to about 20 people) but in situations where there were lots of people, or many people eating and drinking, I was more cautious, and put the mask back on. This might make little sense, healthwise, but aligned with my personal “risk budget” where I spend a little more risk in some situations than others. It’s not a zero tolerance policy, but one which recognized the pleasures of some things — like going to a bar with some co-authors you have not seen in years — were worth the associated risks.

What I can tell you is that it definitely feels odd to be the only person in a room full of about a hundred people wearing a mask.

No-one cast me a hostile gaze, or questioned my choices. But human beings are social creatures. When one person is behaving in a way at odds with the herd, it sticks out. I also felt that I was perhaps reminding my hosts of the virus they had moved on from, had not, in fact, disappeared. They had not really forgotten, of course. People are still getting sick, including two colleagues I had hoped to meet. But I couldn’t help but feel that my facemask put the virus back to the front of mind.

How did it feel for me? Honestly, it was mixed. Maryland, the state where I live, has a similar population rate to Denmark, and similar vaccination rates. According to the New York Times, the infection rate is about about 6 per 100,000, while the infection rate was 270 per 100,000 in Denmark during my visit. So I was exposing myself in ways I had trained myself not to do at home. In Denmark, I veered toward quieter coffee shops, and enjoyed small dinners at someone’s home more than at a restaurant. My main concern was not catching COVID and being stuck in Denmark for an extra couple of weeks. And so, I felt more relaxed during my final day after I had gotten my required test for travel.

It felt undeniably liberating to be in a place where the visible signals of a two-year pandemic were absent. In the previous week I had been in New York at a small conference, and the group moved back and forth between positions, wearing our masks most of the time, except when we spoke, or dining together, but behind a plastic partition that made conversation almost impossible. We were trying to recognize that people had different risk profiles and preferences, but we also privately noted that much of what we were doing felt like safety theater. It felt good to be done with such half-measures while in Denmark.

Are we still governable?

Most of my writing on this blog is about government politics, policies and implementation. But governance is in many respects a co-production. It depends upon the co-operation of the public to function, and the trust — in government, and each other — necessary for such co-operation. In Denmark, I saw a people that trusted their government, and as a result could make real collective decisions, drained of the polarizing conflict that characterizes the United States. That sense of collective purpose — the sense that we are in this together, that we have restored normality after making shared sacrifices — has an intrinsic value to not just government outcomes, but also to how we feel about each other, for the type of society we live in.

If you enjoy my writing, please check out this piece about COVID and institutional distrust, consider subscribing if you have not done so, and share with others!

This is not true. I went to Denmark because I was part of a dissertation defense at Aarhus University where I am a visiting professor. But there is a genre of writing where declaring that “so I went there to find out” seems to be more important, so I am including it in the piece even though it’s not true.

This is my guarantee to you dear reader: any lies will be fact-checked in the footnotes.

Since I’m not a journalist, and didn’t present myself as one to people I talked to. I am not going to quote anyone by name, and hope no-one is offended if they recognize themselves being quoted! Since I spent time at a university, the obvious bias is that the folks I talk to are better-educated, but this sort of bias normally facilitates more support of health restrictions that I did not find.

Again, this is not a health piece, I am not a health expert, and so will not adjudicate these claims. It is the case that deaths recorded with COVID are certainly increasing. The Danish Ministry of Health has set up a page to counter what it sees as misinformation about the Danish approach and outcomes, arguing the current period is not associated with excess deaths. You can see a good account of the logic for the Danish approach laid out in the twitter thread below.