Debunking the false comparisons between European and American abortion policies

Why are conservatives talking approvingly about European abortion policies anyway?

With the Dobbs decision, a curious thing has happened. I’m not talking about SCOTUS stripping away a previously established a constitutional right, which is more deeply disturbing than curious. I’m talking the sudden enthusiasm among Conservatives to talk about European abortion policy.

Ilya Shapiro (in a now deleted tweet) pointed out that the abortion gestational cut-offs for France were 14 weeks, compared to the 15 weeks in the Mississippi law that the Dobbs case was decided on. Defenders of Governor Glenn Youngkin’s proposal of a 15-week cut-off in Virginia or Florida’s new abortion law are also surprising Europhiles.

It’s not just conservatives. After the draft Dobbs opinion was leaked Bill Maher told his viewers: “Like, in Europe, the modern countries of Europe, [are] way more restrictive than we are or what they're [the Supreme Court] even proposing. If you are pro-choice, you would like it a lot less in Germany and Italy and France and Spain and Switzerland.” Noah Smith posted this to his 257K followers after the Dobbs decision.

This claim also featured in the majority Dobbs opinion, and it’s likely to be a recurring talking point in the fall election and perhaps for years to come, so it’s worth taking seriously.

The point seems to be a) that US abortion laws were wildly permissive pre-Dobbs, and b) that a reasonable compromise on abortion can be found if liberals would just use the same standard as in their beloved Europe.

Is this right? It certainly feels surprising.

In short, it is mostly incorrect if you take a comprehensive view of abortion access. The argument strategically focuses on one aspect of abortion access — gestational cut-off limits — where America was generally more liberal than Europe, and ignores other criteria to paint a misleading picture. People might disagree on how much to weigh these other criteria, and Europe is not a single country, so there will be some exceptions (for example, Germany is more restrictive than most of its neighbors). But at the very least, we should avoid avoid the mistaken view that there is a single, valid measure of abortion access that can be used across countries.

A comprehensive view shows that abortion is generally mostly more accessible in Europe on most criteria than in the US. It was pre-Dobbs, and it is going to be dramatically more so post-Dobbs.

When Pam Herd and I wrote about administrative burdens in abortion policy we had ample opportunity to think about access from a comprehensive perspective, and so I will draw extensively from our book.

Gestational cut-offs

Let’s start with the gestational cut-off point, the key metric used above. The US, by allowing up to 24 week cut-off (though limited it to 20 or 22 weeks in many states), was indeed more liberal than most other countries on this basis.

The gestational cut-off is an attractive measure of access because of its simplicity. But that simplicity can also be misleading for three reasons.

First, the cut-off point is not representative of the actual practice of when abortions occur. Just 1% of US abortions occurred after the 21 week point, and 91% occurred before 13 weeks. So why allow a late and rarely used cut-off? Women are more likely to select an abortion at that point because of health risk either to themselves or the fetus. Having that option is important for women forced to make some hard choices.

Second, in other countries the gestational cut-off is more flexible than it appears. A legal brief prepared by international and comparative legal scholars summarized this point:

Looking at abortion laws in their broader context reveals that comparable countries which, on their face, set shorter time limits on abortion access than the United States, often provide greater flexibility in obtaining abortions after those limits pass, with exceptions for a broad range of circumstances.

For example in Germany, there is a nominal 12 week limit, but:

exceptions include when— “from the [pregnant person’s] point of view”—abortion is “necessary to avert a danger to the life or . . . grave injury to the mental or physical health of the pregnant [person],” taking into account her “present and future living conditions.”

Thus 12 weeks might not really be 12 weeks. The seemingly clear measure of access becomes more complex.

Third, gestational limits are only one aspect of abortion access. What are the others?

Access: Hospitals vs. clinics

In 1973, eight in ten abortions in America were performed in hospitals. The politicization of the topic after Roe made hospitals wary of being associated with such a contentious issue. By 1996, nine in ten abortion were performed in clinics. As the service became separated from hospitals, it also became even more politically and physically isolated. Women seeking abortions, or those working at clinics could be more easily identified and targeted with protest and sometimes violence for abortion providers.

In Europe, this Roe-era separation did not occur. Though clinics exist to varying degrees, the reliance on hospitals to provide abortion, and thus the treatment of the abortion as a normal health service, is more frequent. Where clinics exist, politicians in even fairly conservative countries like Spain can do more to restrict protest around the clinic.

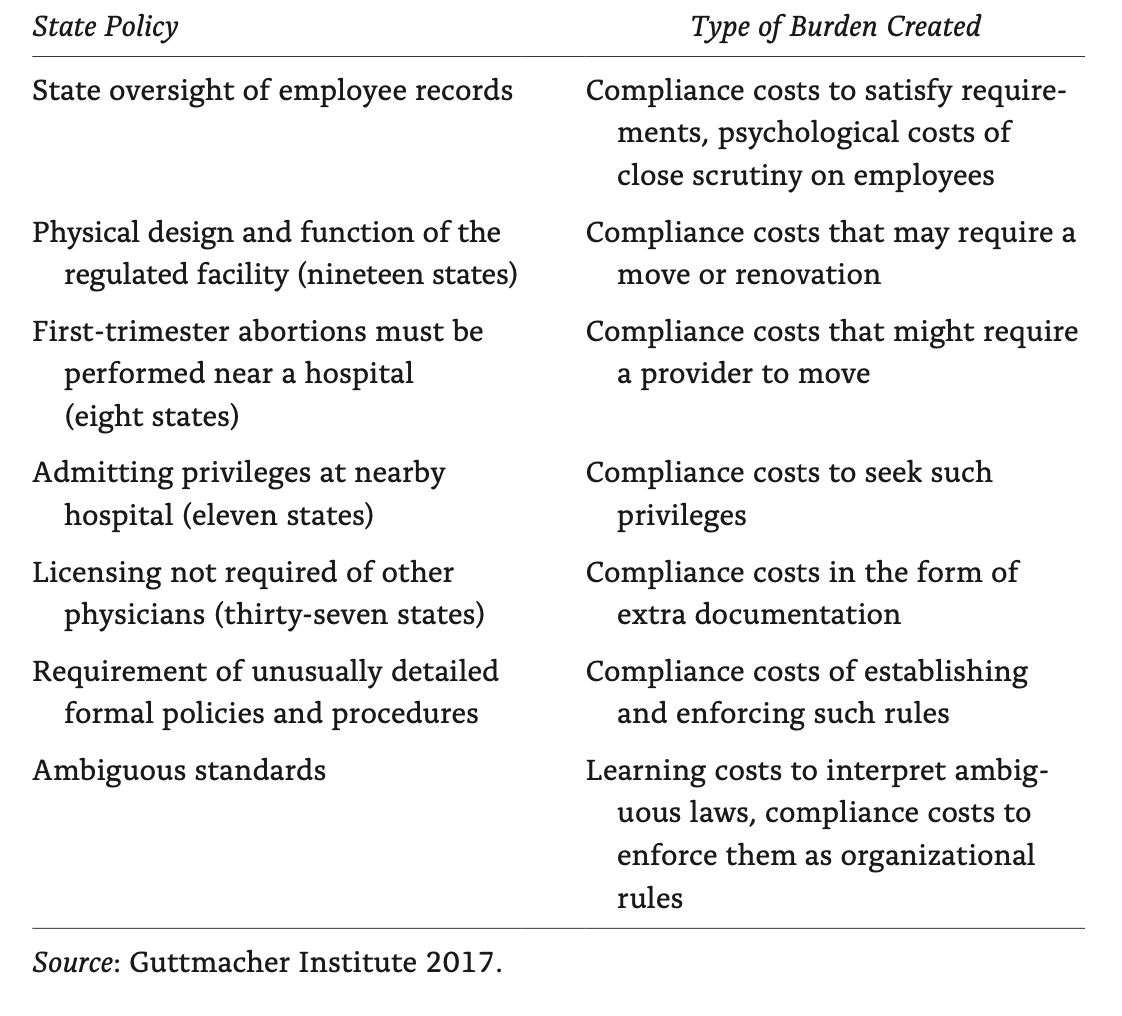

TRAP laws imposed on abortion providers

The separation between hospitals and clinics also enabled anti-abortion regulators to impose burdens onto abortion providers that they did not apply to other health providers. Thus, the isolation of abortion clinics beget Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers (TRAP) laws that made it infeasible for clinics to operate. In our book on administrative burden we identified the costs these laws for clinics and patients.

TRAP laws were effective in closing down abortion providers, making the service more geographically remote. By the time the Dobbs case went forward, there was just a single abortion provider for the whole state of Mississippi.

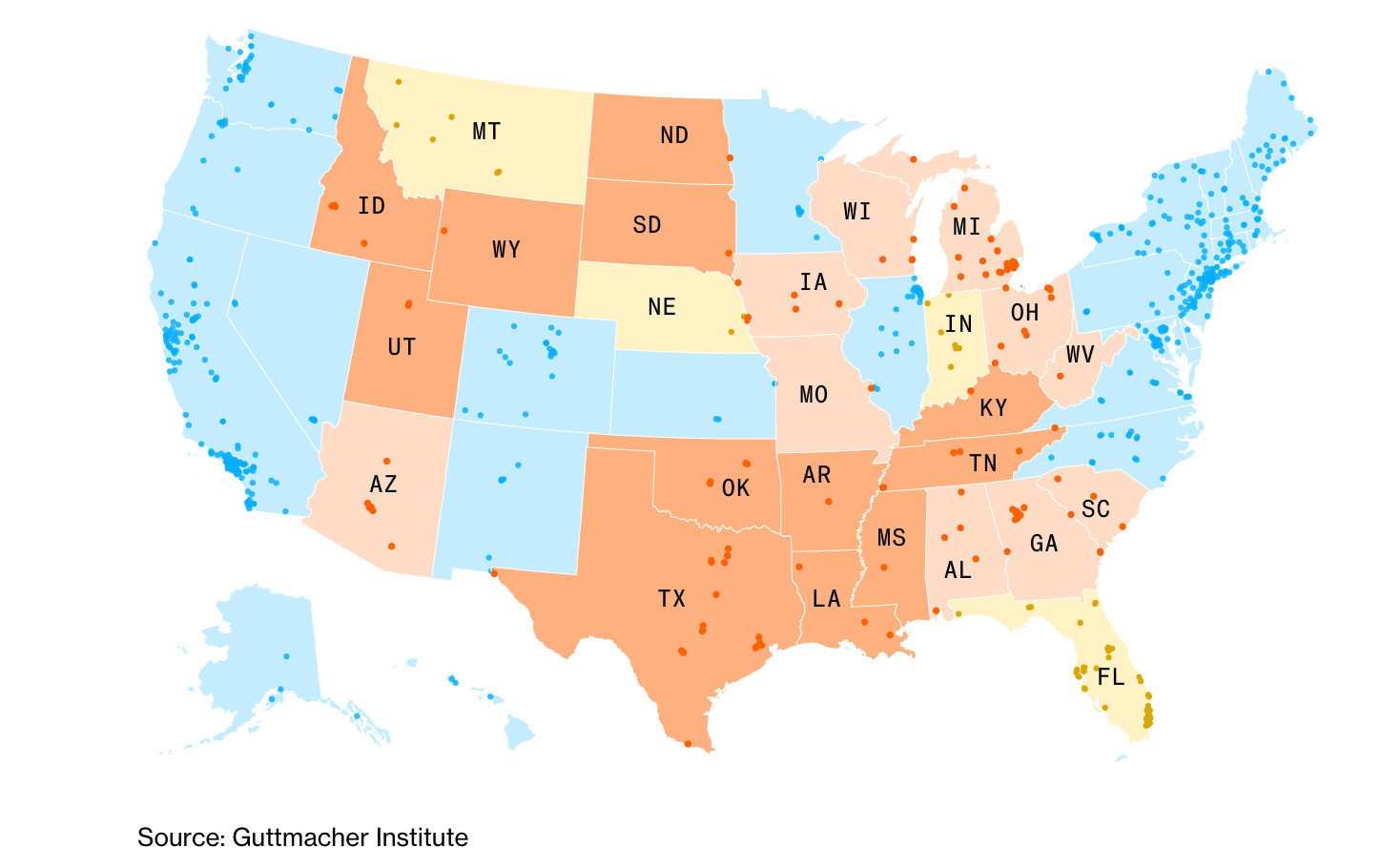

A map of pre-Dobbs providers shows the uneven distribution of access to abortion, which reflects the severity of TRAP laws in some states.

Post-Dobbs, such abortion deserts will get much worse. One quarter of clinics are expected to close, disproportionately concentrated in states where there are already few if any alternatives. Women in 26 states will have to travel an average of 552 miles for an abortion.

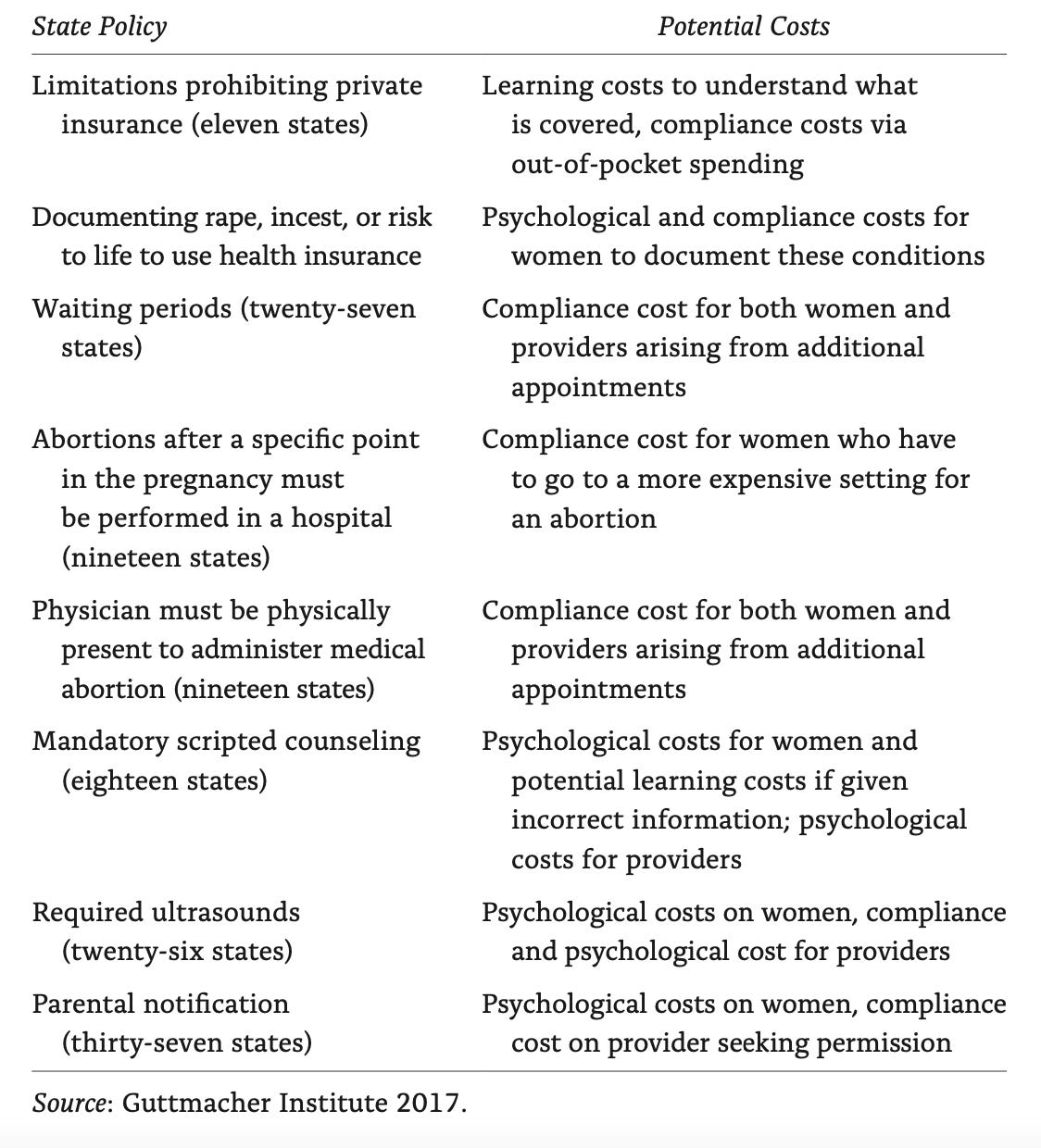

Compliance costs imposed imposed on women

TRAP laws did not just focus on providers — they also targeted women directly. Here is a list of those laws and how they deliberately sought to reduce access. Any discussion of abortion laws or access that does not account for these policies is hopelessly, and perhaps deliberately, incomplete.

TRAP laws do not just close clinics, they reduced abortions, and in doing so limited educational attainment and economic mobility, especially for Black women.

It would be wrong to suggest that Europe has no equivalent to American TRAP laws, but European versions are less frequent and severe in nature. For example, 16 countries have mandatory waiting periods, compared to 27 states in the US; 13 countries have mandatory counseling compared to 18 US states.

Financial costs

TRAP laws make the provision of abortion services more expensive, both for providers and clients. Women have to travel further to find a clinic. Because of waiting periods, they might need to book a hotel, and take time off work.

Women in the US have less financial support to overcome those costs. Because of public health insurance, abortions in Europe are generally free or highly subsidized. By contrast, in the US, the Hyde Amendment prohibits spending federal dollars on abortion services. Many states also limit public funding, and even private insurers from covering the service. The net effect is that women are generally personally financially liable for the cost of an abortion, unlike their peers in Europe.

How big is this effect? Again, from Administrative Burden:

In 2008, only 12 percent of abortions were paid for by private insurance. Many with health insurance still end up paying for the service. One survey of women at abortion clinics found that though only 36% of the sample had no health insurance, 69% were paying for the service out of pocket. The 46% of women who did not try to seek reimbursement believed (often correctly) that the service was not covered. For these women, the average out-of-pocket costs for an abortion was $485, increasing to $854 for a second trimester abortion. Lost wages (an average of $198), transportation costs ($44), childcare costs ($57), and other costs ($140) drove the compliance costs higher.

To put these costs in perspective, less than 4 in 10 families can raise $1,000 in case of a financial emergency. It is reasonable to assume that women who feel compelled to seek an abortion will be in an even weaker financial position.

Child-rearing supports

If abortion is relatively expensive in the US, so too is having a child. Giving birth costs an estimated $4,500 in out-of-pocket expenses, meaning that many new mothers leave the process with significant debt. Add in the lack of paid family leave, or a child allowance, two standard features of the European safety net, and women in America who are unable to cover the financial cost of an abortion because of state restrictions can’t count on much help with the ensuing birth. The best evidence we have, The Turnaway Study, finds that:

Women denied a wanted abortion who have to carry an unwanted pregnancy to term have four times greater odds of living below the Federal Poverty Level.

A false compromise, and real outlier status

One truly disingenuous aspect of the comparison between European gestational cut-offs and those in the Dobbs case is that neither the state of Mississippi nor the majority of the Supreme Court wanted a 15 week cut-off for the state. There was precisely one vote in the court for such a compromise, which was Chief Justice Roberts. The actual practical effect of the Dobbs decision was not to move to a 15 week cut-off but to trigger an older law that prohibited any abortions in the state with the exceptions for rape or the life of the mother. It is more likely that Mississippi will remove those exceptions rather than pass a more liberal law.

Even in the states where 15 week cut-off is a a real offer — lets say Virginia — this does not make it equivalent to access to abortion in, say, France because it would require changing social supports, financial barriers and physical location of abortion access. There is no American state that really looks like Europe for that reason.

Post-Dobbs, some parts of America will start to look more like some parts of Europe. Specifically, red states will look similar to the handful of countries where abortion is largely restricted and where just 5% of Europe live: Andorra, Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco, Poland and San Marino. Before Dobbs, 21% of American women lived in states with trigger bans that prohibit abortion in almost all cases, and this number will increase as other red states adopt similar policies, or as in states like Wisconsin, pre-Roe laws stay on the books.

If the goal of pro-choice actors in encouraging us to look to Europe was to suggest that the US was an extreme outlier pre-Dobbs, it achieves the opposite outcome: much of the US will now be an extreme outlier post-Dobbs.

In another way, the US stands as an outlier, in resisting a general trend toward liberalization.

Comparing abortion laws globally, a 2022 Council on Foreign Relations report said the past 50 years have seen "an unmistakable trend toward the liberalization of abortion laws, particularly in the industrialized world."

By its review, 38 countries have changed their abortion laws since 2008, and all but one of those changes "expanded the legal grounds on which women can access abortion services."

In short then, Europe had less permissive policies to abortion only if you consider gestational cut-offs, ignore flexibilities in how those cut-offs operate, and other important aspects of abortion access, such as physical location, intrusive TRAP laws and financial costs. In large part this is because anti-abortion American policymakers who could not ban abortion or alter gestational cut-offs because of Roe spent decades finding ways to restrict abortion on every other dimension they could think of.

Post-Dobbs, the comparison with Europe falls apart completely, except that lots of American women now face the same draconian policies as a tiny number of European women who live in places like Lichenstein.

Sometimes comparisons clarify, and sometimes they obscure. In this case, it seems better for Americans to focus on how to restore reproductive rights that were lost. If we are to look to Europe it should be to acknowledge and correct the many ways women in America already struggled to access what was, until recently, a constitutional right.

Please subscribe if you have not already, and consider sharing. You can read the archive, for free, here: