Policymakers in recent years have become more interested in reducing unnecessary administrative burdens on the public. But to do so, they need to first be able to identify those burdens, and that means measuring them. Because, as the old adage goes, what gets measured gets managed. If you can’t measure a problem in government, it is very easy to overlook it.

So for much of the last year, I have been thinking a lot about measuring the time tax that government imposes on the public. And I have three things I want to share about that topic.

Measuring the experience of burdens

How might governments judge if their programs are too burdensome? There are a few approaches. The obvious place to start is to look at at take-up levels - which programs have high or low take-up among their eligible population? Take-up is not the same as burden, but there is a good chance that if a program is offering a valuable service, and has low take-up, burdens are the problems.

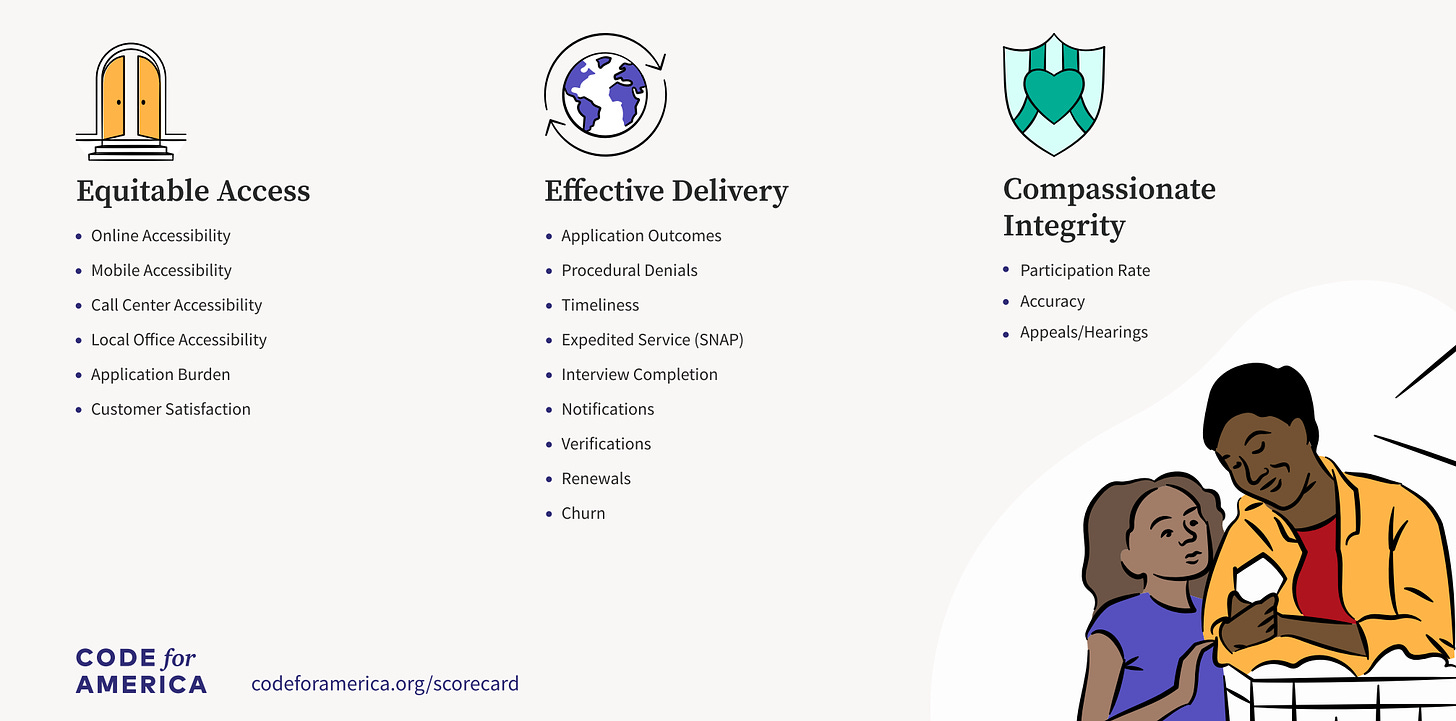

Another approach is to look at objective measures of user experience. Code for America has developed a comprehensive scorecard in the context of safety net services, including how much time it consumes. Each of the items below

The New South Wales government in Australia has taken Cass Sunstein’s idea of sludge audits, and developed toolkits to identify sludge in services. This is a useful tool for those working within government who want to gain a rough sense of where hassles lie in existing processes and to understand what best practices might exist to reduce them.

My insight from spending a lot of time studying performance management in government is that you need different tools and different measures for different purposes. One tool that has been missing is specialized measure of user-experienced burden.

So Sebastian Jilke, Pam Herd, Martin Baekgaard and I set out to create a measure of burdens that could be be easily adopted in user surveys, with research support for Schmidt Futures. Our goal was to create something short and easily adaptable, which could be embedded in user surveys when people interact with government, which we hope will become more and more common. We tested this on a sample of SNAP users. The results of this peer-reviewed research are now published and open access in The Journal of Behavioral Public Administration:

We developed both a single use item…:

Overall summary item: “We want to hear about your most recent experiences with [program/process]. This includes applying for AND/OR renewing your benefits. Please think about your most recent experience with the program when you respond to the question. How would you describe this experience overall?” (Response categories: Very difficult, somewhat difficult, neither easy nor difficult, somewhat easy, very easy.

…and a three-item scale that captures learning, compliance and psychological costs:

We want to hear about your most recent experiences with [program/process]. This includes applying for AND/OR renewing your benefits. Please think about your most recent experience with the program when you respond to the question.

Learning costs: How difficult was the process of finding information about the program, such as how to apply or what you needed to do to renew your benefit? (Response categories: Very difficult, somewhat difficult, neither easy nor difficult, somewhat easy, very easy).

Compliance costs: How was the process of filling out the paperwork, providing proof of eligibility (such as pay stubs, proof of residence, birth certificates, etc.), and/or attending interviews? (Response categories: Very difficult, somewhat difficult, neither easy nor difficult, somewhat easy, very easy).

Psychological costs (frustration): Please describe how you felt during these experiences? (Response categories: FRUSTRATED: Extremely, very, moderately, slightly, not at all).

You can read more detail about scale validation in the article, which includes tests of predictive validity. We find that people are more likely to report burdensome experiences when they have poorer health, lower education, experience financial scarcity, are younger and have less experience in interaction with SNAP.

We compared the scale to the existing customer experience survey items recommended by the federal government. The two scales are correlated, as one would expect, but not highly so, suggesting they capture different aspects of people’s experiences. The shorter burden scale explains more of the sources of variation in potential sources of inequality than the seven-item CX scale.

Having developed the scale, we are now testing it in field settings with Code for America to further validate it, and to learn more about why some people experience more burdens than others. Anyone is welcome to use the scale, but please let us know if you do so, since we are curious to learn how it will be used.

Measuring burden tolerance

Everyone has a story of frustrating encounters with government, so a profound puzzle is why we put up with them. Why do we tolerate burdens? A new research paper with Martin Baekgaard and Aske Halling, forthcoming in Public Administration Review, seeks to both develop a measure of burden tolerance, and to understand what drives burden tolerance in different settings. One reason for developing such a scale is that much of what we know about burden tolerance comes from asking people about burdens in social policies, which might reflect their attitudes toward social policies rather than burdens more generally.

Using data from 12 surveys in seven countries we developed a four-item scale of burden tolerance (1= strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree):

It is acceptable that people face some hassles when they are in contact with the government

If people want to access public services and benefits, it is only fair that they have to make a significant effort to get them

People should be responsible for figuring out how to access government services themselves; it is not the government’s responsibility to help them

It is acceptable that people sometimes feel that it is difficult and time-consuming to apply for government services and benefits

Across multiple countries, we find a number of consistent predictors of burden tolerance. Women, older adults, those with higher education and those in poorer health are generally more opposed to burdens. People who identify with a conservative ideology and trust the state are more likely to support burdens.

The scale is good for asking people about their general attitudes toward burdens, but can also be adapted to specific policy areas. Our generic scale correlates highly with the tolerance for burdens in such diverse domains as income supports, health insurance, passport renewals, and small business licensing. As with measuring the experience of burdens, we see this work as an early step in accumulating insights rather than a last word, so hope other researchers engage with the question.

What I’m reading:

Some pieces that grabbed my attention in the last couple of weeks.

Suicide Mission by Maureen Tkacik at The American Prospect: The destruction of Boeing's safety culture by executives should be a warning for our government: experience matters, leaders who hate the career experts don't have the capacity to manage the risk they create when they outsource core tasks.

The IRS Finally has an Answer to TurboTax by Saahil Desai in The Atlantic: I’ve written previously about the multi-decade battle for the IRS to create a free digital tax filing system, despite the opposition of the private tax return industry who prefer that taxpayers continue to pay them. This article gives a first look at an IRS pilot for this effort, and offers reason for cautious optimism.

On "Liberating Evaluation from the Academy": Jen Pahlka asks why there isn’t more implementation in public policy degrees, and whether its possible to embed an evaluation ethos into government.

Great work; this is really exciting. My daughter lives in a state where the IRS filing is available and I can't wait to find out what she thinks about it.

Since opinions about burdens in social policies might reflect attitudes toward social policies, would it be useful to also ask about burdens from corporations, to get a comparison? For instance, from cable companies or phone companies or airlines or anyone else famous for making us jump through frustrating hoops.