ABLE is a Program to Help People With Disabilities Achieve Financial Independence: Why is it so Underused?

To Make ABLE Work, Reduce Administrative Burdens

Regular readers of this blog are familiar with the administrative burdens that many Americans face when accessing benefits for which they are eligible. Such barriers can be particularly high for Americans living with a disability and their loved ones. New research we have undertaken shines a light on significant burdens in ABLE, a promising new savings program designed to help individuals with disabilities achieve greater financial independence.

Americans who live with disabilities face distinctive financial challenges, many arising from the high costs of navigating life with a disability. Many people with disabilities depend upon Supplemental Security Income (SSI) and Medicaid for baseline income and otherwise unaffordable health costs. Yet asset limits associated with those programs hinder efforts by SSI recipients and their families to address these challenges and promote their financial security. Under current rules, SSI recipients cannot accumulate more than $2,000 in countable financial assets. The $2,000 cap constrains the ability of SSI recipients and their families to set money aside for emergencies, to invest in training and upskilling opportunities, or simply to spend on activities that are important to their independence and well-being. Despite various efforts to address this issue, the asset cap was last raised in 1989 and has declined by more than 75 percent in real value since the mid-1970s.

In 2014, Congress (with virtually unanimous bipartisan support) passed legislation to create “Achieving a Better Life Experience” or ABLE accounts. These accounts allow eligible persons who acquired a disability before age 26 to open tax-advantaged savings accounts. These programs are sponsored and administered by state governments. Modeled on the basic structure of 529 college savings accounts, ABLE accounts allow SSI recipients to save up to $100,000 without endangering their SSI benefits. When ABLE account balances exceed $100,000, SSI cash benefits are temporarily suspended until the ABLE account balance decreases to below that threshold. Medicaid benefits continue unaffected.

ABLE account assets can be used for nearly any expense that benefits the account owners’ health, independence, or quality of life. These can include car and wheelchair repair, transportation expenses, even rent and food. For many recipients, ABLE accounts effectively nullify the $2,000 asset limit.

Despite the program’s attractive features, and nearly 10 years since the ABLE legislation passed, very few eligible Americans own an ABLE account: roughly one percent of eligible SSI recipients. Particularly striking, only 2.6% of SSI recipients whose cash payments were specifically suspended because of excess income possess such accounts. In a recent survey of people with disabilities, only seven percent reported being familiar with ABLE accounts.

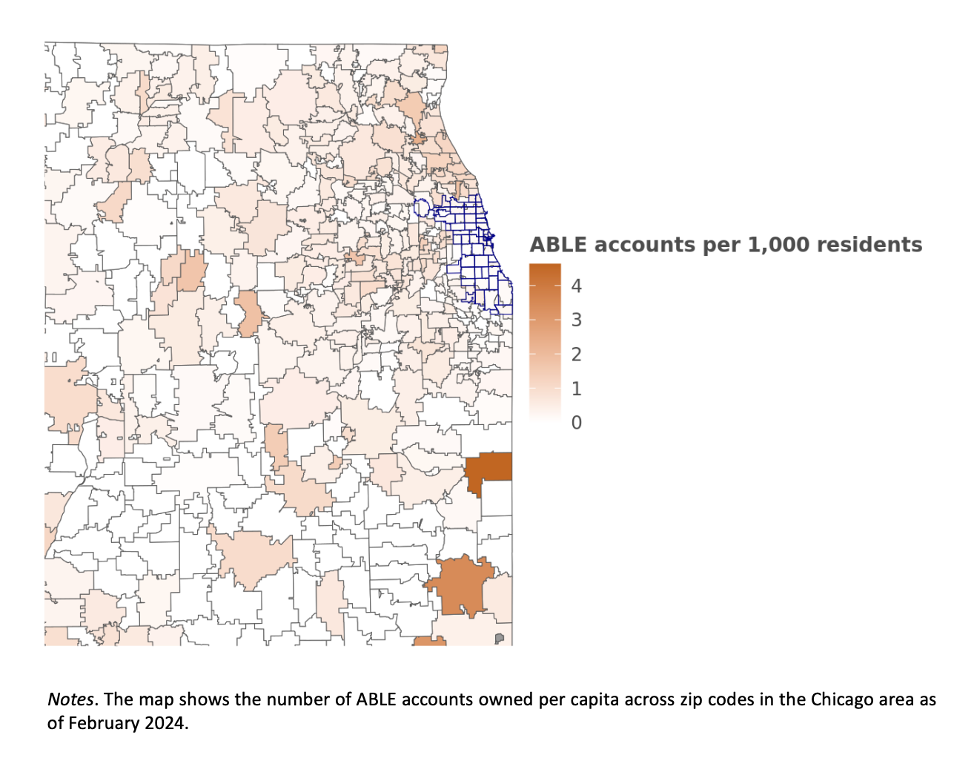

So why isn’t ABLE more popular? Our research suggests that—similar to other programs offering tax advantages—low awareness and compliance complexity associated with ABLE accounts exacerbate intersectional inequalities. Within Illinois, the areas with the highest rates of ABLE account ownership include greater Naperville and Chicago’s northern suburbs—areas known for their affluence. Meanwhile, low-income areas such as Chicago’s South and West sides, which include large populations of SSI recipients with disabilities, include virtually no ABLE account owners. The top 12.3 percent of accounts in Illinois hold fully half of the state’s total ABLE financial assets, while the bottom 50 percent of accounts contain less than nine percent of Illinois’ total ABLE account assets.

ABLE Accounts are Concentrated in More Affluent Areas

In our study, we offered a $100 sign-up bonus to anyone who opened an ABLE account. But the incentive had little effect. We worked with more than a dozen disability advocacy and service organizations and groups to send direct emails to thousands of people. We also worked with organizations to share the recruitment information on their social media platforms such as Facebook groups and during in-person events. Yet only 40 people (out of the 400 we budgeted for) took advantage of this opportunity and opened a new ABLE account.

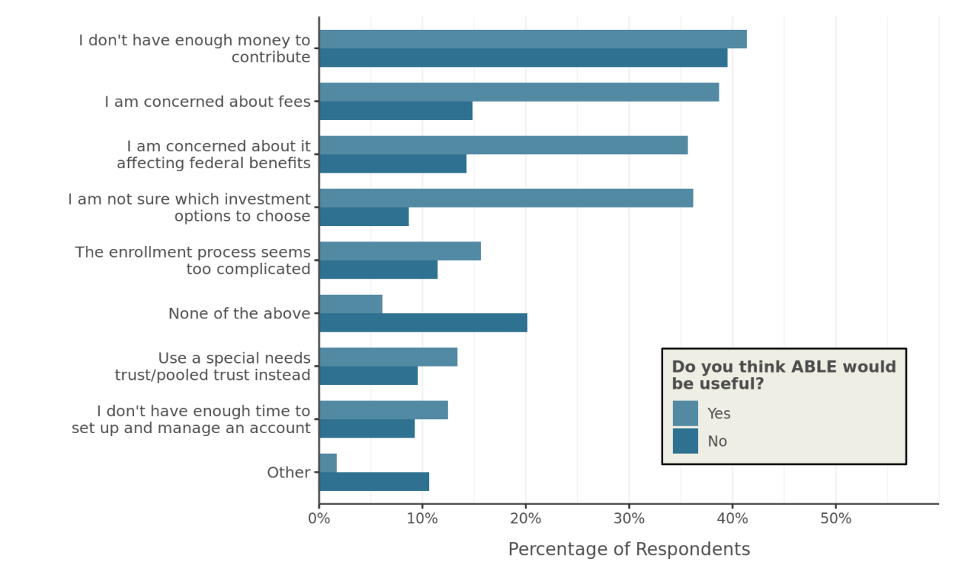

Through a mix of structured interviews, surveys, and analysis of administrative data, we identified three main barriers that make it difficult for people to open an account: (1) financial constraints; (2) learning costs; and (3) compliance costs. The latter two might be particularly familiar to readers of this blog.

Financial constraints

ABLE requires the ability to set aside money. People’s limited income and resources were the most widely cited barrier to opening ABLE accounts. Several interviewees and survey respondents who had not opened an account told us that ABLE accounts might not be useful given an inability to contribute to the account. Such constraints reflect the life circumstances of most SSI recipients. To qualify for SSI, people with disabilities must have quite limited earnings and assets. Thus, they may not have enough money to save. More generally, people with disabilities face substantial challenges to financial independence. As identified in national surveys, only 10 percent of people with disabilities were characterized as financially healthy (versus 30 percent of those without disabilities). Seventeen percent lived in households with less than one week of expenses saved.

Barriers to Opening an ABLE Account

Learning costs

Learning costs refer to the time and effort potential beneficiaries must invest to understand the program, determine their eligibility, and comprehend the nature and accessibility of the program’s benefits. In addition to low awareness about the program, an important barrier was understanding the program rules. One person we interviewed said:

I’ve had a special needs daughter for 20 plus years, and I do public policy research, … and I look at this stuff and it’s like “I can’t figure this out.” So, I think a lot of people just look at it, it’s like “Well, I’ll look at it someday.” But just don’t have the time to figure it out.

Even among people who opened accounts, some misunderstood features such as what their savings could be used for and how much money they could save without affecting SSI benefits. Respondents’ misunderstandings of these key features were essentially unchanged even when we surveyed them six months after they had opened a new ABLE account.

Compliance costs

Compliance costs include efforts and expenses that arise from gathering information and documentation required to demonstrate continued service eligibility and compliance with administrative requirements. Many eligible individuals remain erroneously concerned that opening an account may affect their SSI benefits. Among the small set of 40 people who opened a new ABLE account in our pilot, 35 cited the opportunity to save without impacting eligibility for federally funded benefits as a key motivating factor. Other compliance costs, including the perception of a difficult enrollment process and uncertainty around which investment plan to choose, also served as barriers.

Simple measures than can help

ABLE accounts are a new and valuable tool to address a serious policy failure: SSI’s $2,000 resource limit. ABLE accounts can help SSI recipients save for emergencies and for the future, and to invest in their own personal development without jeopardizing their benefits. ABLE program administrators state that while ABLE accounts cannot fully address long-standing barriers facing SSI recipients, the accounts provide many benefits: the ability for families and others to contribute to the financial wellness of a person with a disability, incentives to work, the protection of SSI benefits, and tax advantages for many families.

If policymakers want ABLE accounts to succeed, they should look to limit the learning costs and compliance costs that now dissuade many people from opening or using such accounts. Some easy fixes include simplifying the enrollment process and helping to assuage people’s concerns.

Using plain language would help. For example, the term “qualified disability expenses” might create uncertainty as to what counts as a valid use of funds. Instead, the terminology could be simplified to be clear that any expense that benefits the account owners’ health, independence, or quality of life is a valid use of funds.

Investment decisions can also be simplified by defaulting new account owners into a low-cost investment plan that offers modest returns with little risk, with an option to change investment selection at any time after enrollment to an appropriate moderate-growth fund or other asset that matches the life circumstances of the ABLE account holder. Finding ways to limit program fees, especially for those with low balances, would help people who already face extensive financial challenges to realize the benefits of these accounts. Further, building on and expanding targeted efforts to reach under-represented communities should be made to increase awareness of the program, in Illinois and across the nation.

Other, simpler tools are also needed, that match the life-circumstances of most SSI recipients and their families. The most-straightforward initiative would be to raise SSI’s resource limit to its inflation-adjusted value of the early 1970s. Bipartisan legislation, including the SSI Savings Penalty Elimination Act, has been proposed to implement such a policy.

ABLE is a relatively new program, which is both why people face learning costs and why we need more research to make it work better. Our team is partnering with SSA and the Illinois State Treasurer’s Office to launch a large randomized controlled trial in Illinois early next year to test cost-effective and scalable solutions to help more eligible individuals and their loved ones open ABLE accounts. If you would like to learn more about this initiative, please don’t hesitate to reach out.

Guglielmo Briscese is Research Associate at the University of Chicago Inclusive Economy Lab

Michael Levere is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Colgate University.

Harold Pollack is the Helen Ross Professor at the Crown Family School of Social Work, Policy, and Practice at the University of Chicago.

You know they’ve done a poor job of adverting these accounts when 40+ years social workers in children and families services have never heard of them.

The failure to inform has led to untold suffering for a few generations now.

The lack of funds in accounts that do exist has more to do with the shredding of the middle class, as families overall lost buying power due to government policies that have favored the wealthy now for those 2 generations.

Our personal experience as relatively high resource ABLE users for our son:

1. The state vendors offer crappy high cost products with crappy software. Big players don’t want this low revenue business.

2. You can’t get money out when appropriate because the software is so bad

3. The oversight is the usual “you are a crook and we will get you” set of impossible burdens.

4. NOBODY, including expert accountants, has much confidence about what will trigger an audit.