You Should Be More Worried About Politicization of the Career Public Service

Protecting the civil service has become critical as anti-democratic threats mount

Hypocrisy is a quality that is not exactly in short supply in politics. Recently, as President Biden removed Trump appointees from various advisory committees, we were treated to some remarkable examples.

Kellyanne Conway, serial violator of laws against federal employees engaging in campaign work bemoaned the “politicized” nature of being asked to resign from the Air Force Board of Visitors. It was, she declared, “a break from presidential norms”

Russ Vought, Trump’s former Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) was similarly defiant.

First, let’s clear up whether Biden was is his rights. The answer is yes, both legally…

… and in term of norms. Trump had already booted qualified people like the former Comptroller General of the GAO from a defense advisory board to make room for luminaries like Corey Lewandoswki.

Vought’s pronouncements on this are particularly hypocritical. While advisory boards are not an especially big deal, Vought championed some truly damaging politicization when he was in power. It’s this type of politicization, the use of political control to undermine the career civil service, that I want to talk about. Trump and Vought tried to move the US back toward the era that necessitated civil service systems in the first place: the Jacksonian populism that gave rise to the spoils system, inefficiency, and wide-scale corruption.

Big takeaway: If you are concerned about attacks on US democracy, you should be worried about efforts to politicize the civil service. Any proposed changes to the federal public service should be evaluated in the context of current anti-democratic risks.

Politicization comes in different forms, but the most basic one is the number and use of political appointees – who typically serve at the pleasure of the President, and are selected at least in part for political loyalty.

The US has, in relative terms, a lot of political appointees. About 4,000. That makes us an outlier compared to other rich countries. Despite all the talk of the “deep state” the career civil service – that is employees who can only be fired for cause – is relatively weak in its policy influence and scope. As a percentage of the population, the federal workforce shrank from 1.13 percent in 1967 to 0.64 percent in 2018.

Politicians justify the outsized influence of appointees as providing political responsiveness. Of late, there is an emerging and I think dangerous argument for more politicization: that the President has a constitutional right to fire career employees, which is accompanied by the claim this will improve public sector performance and accountability.

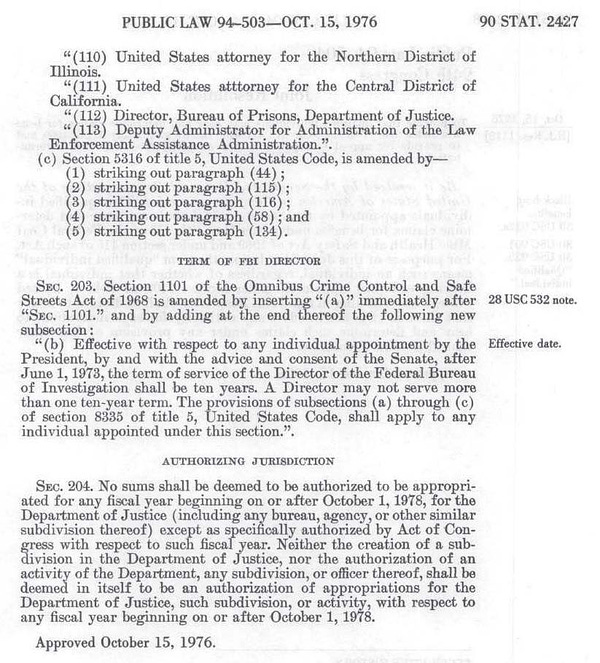

This argument was represented by Executive Order 13957: Creating Schedule F in the Excepted Service, which Trump signed on October 21 2020. Coming right before the election, it drew little attention. What it meant in practical terms is that the President could convert any career official who offered policy advice – which could be hundreds of thousands of employees – into political appointees, stripping them of their career protections, allowing the President to fire them.

Biden reversed Schedule F. But the Trump officials who created it are marketing it as a blueprint for the future of the US public service, and it is very possible that some version of Schedule F will return. So, lets dig in to how it came about, what it entails and why it’s so dangerous.

The idea of Schedule F dated back to 2017. A White House memo proposed that “Article II executive power gives the president inherent authority to dismiss any federal employee. This implies civil service legislation and union contracts impeding that authority are unconstitutional. If so the President could issue an Executive Order for dismissing federal employees.”

The underlying logic of Schedule F draws from unitary executive theory. Conservative lawyers developed this theory justify strong presidential authority for Republican presidents. For example, Trump’s one-time acting head of the Office of Personnel Management and Deputy Director of Management for the OMB, Mike Rigas, questioned if the 1883 Pendleton Act, which forms the basis for the modern civil service, was constitutional, since it impedes upon President Trump’s unitary executive powers. (Aside: the Heritage Foundation has played an outsize role in Schedule F. The author of the 2017 memo, James Sherk was an alum, as was Rigas and Vought).

Schedule F and similar applications of unitary executive power are a bad idea for three reasons: they will worsen public sector performance, lead to more extreme swings between a hyper-politicized public sector, and most importantly, remove an important protection against anti-democratic Presidents.

A more politicized public service leads to worse public performance

Unitary executive proponents of politicization tell a simple story: the President is the only governmentwide officer responsive to the public as a whole, and therefore the only one with a strong incentive to think about administrative performance. This theme has emerged in a string of Supreme Court expansions of presidential removal powers: Lucia v SEC, 2018, Selia Law v. CFPB, 2020, and Collins v. Yellen 2021. For example, in Selia, Chief Justice Roberts claimed that “entire ‘executive Power’ belongs to the President alone” and that “the Framers made the President the most democratic and political accountable official in government.” In Collins vs. Yellen, Justice Gorsuch wrote: “It is the power to supervise—and, if need be, remove—subordinate officials that allows a new President to shape his administration and respond to the electoral will that propelled him to office.” It is perhaps unsurprising that the current SCOTUS is open to such claims, since the majority of the court were themselves political appointees as well as tied to the conservative legal world that created the unitary executive theory.

What is the problem with this argument? The story of how a powerful president improves government performance is confounded by the managerial missteps of the Presidents whose administrations most avidly embraced unitary executive theory, George W. Bush and Donald Trump.

The politicization of the public service under Trump offered a preview of how Schedule F would be used. Trump routinely ignored experts, sidelined those whose evidence ran contrary to his views and stacked his administration with unqualified appointees. In a context where the President routinely misrepresented information, including during a pandemic, the ability of a civil service operating under Schedule F to insist on evidence-based policymaking and communication would be undermined, and public trust in government processes would decline.

Researchers, most notably David Lewis of Vanderbilt University, have tried to systematically understand the effects of politicization. Their work shows that appointees are associated with lower federal government performance and less responsiveness to the public. There simply is no body of evidence that suggests that allowing partisans to fire career officials in highly politicized settings improves performance. Indeed, what evidence we have suggests the opposite.

Civil servants develop expertise precisely because a stable public job provides an environment where they can pursue their motivation to make a difference. Stephen Skrowonek, the great scholar of the administrative state, notes the unitary executive theory is in direct conflict with administrative expertise: “It discounts the notion of objective, disinterested administration in service to the government as a whole and advances in its place the ideal of an administration run in strict accordance with the President’s priorities.”

Let’s go back to Russ Vought, who enthusiastically embraced Schedule F, and set a target of converting 88% of his career OMB staff to political appointee status. How did they respond? OMB employee engagement scores plummeted from 76% to 55% in the last year of the Trump administration, the lowest among all small agencies. The perception that OMB leadership was effective dropped from 45% (already low) to 30%. Again, this fits with rigorous studies that show that instability and politicization makes public service less attractive, leading to higher turnover of experienced civil servants, and giving public officials less reason to develop expertise.

Politicization leads to a polarized public service

We bemoan the polarization of our political system. Increasing the number of political appointees would create a new venue where such polarization could undermine the quality of governance by replacing moderates with extremists.

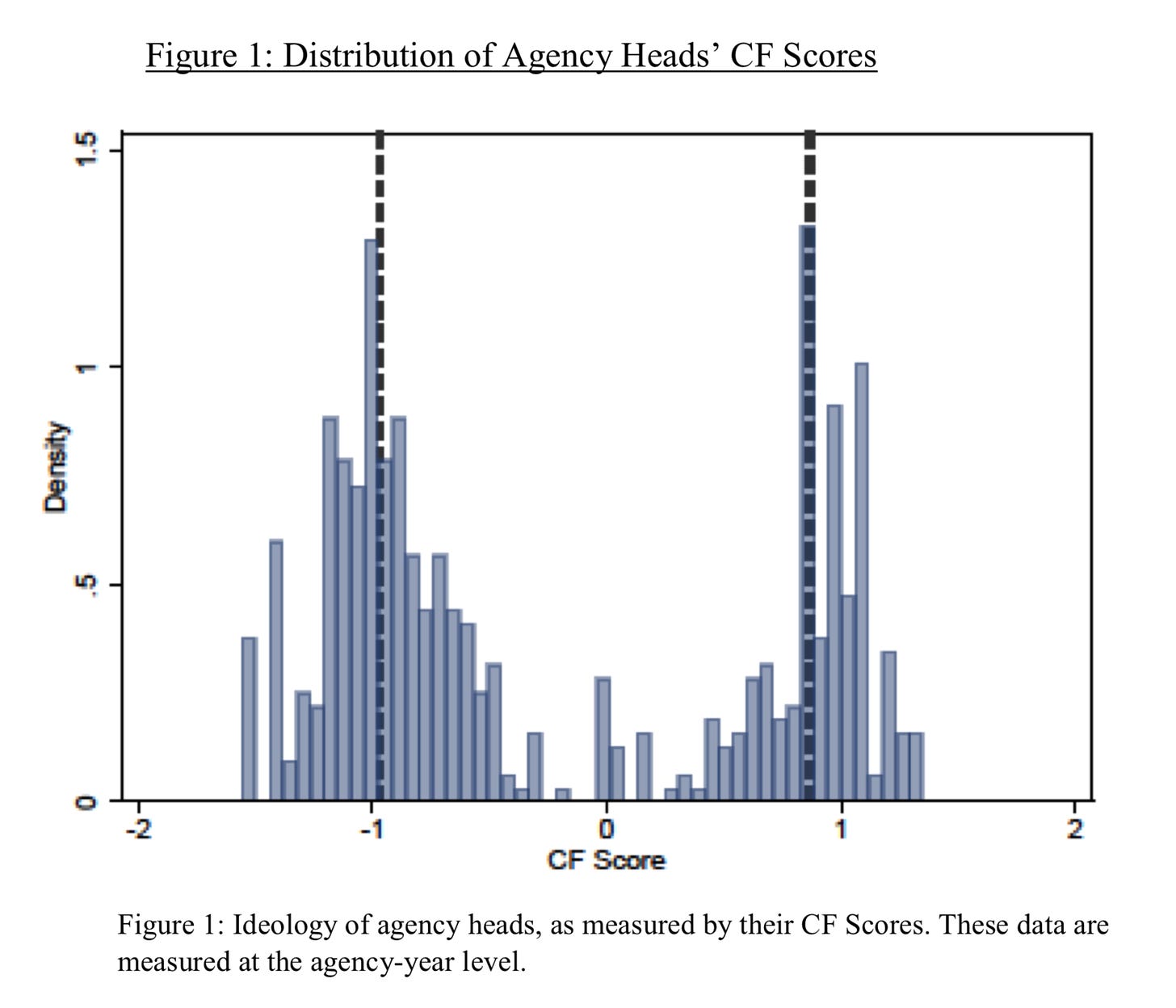

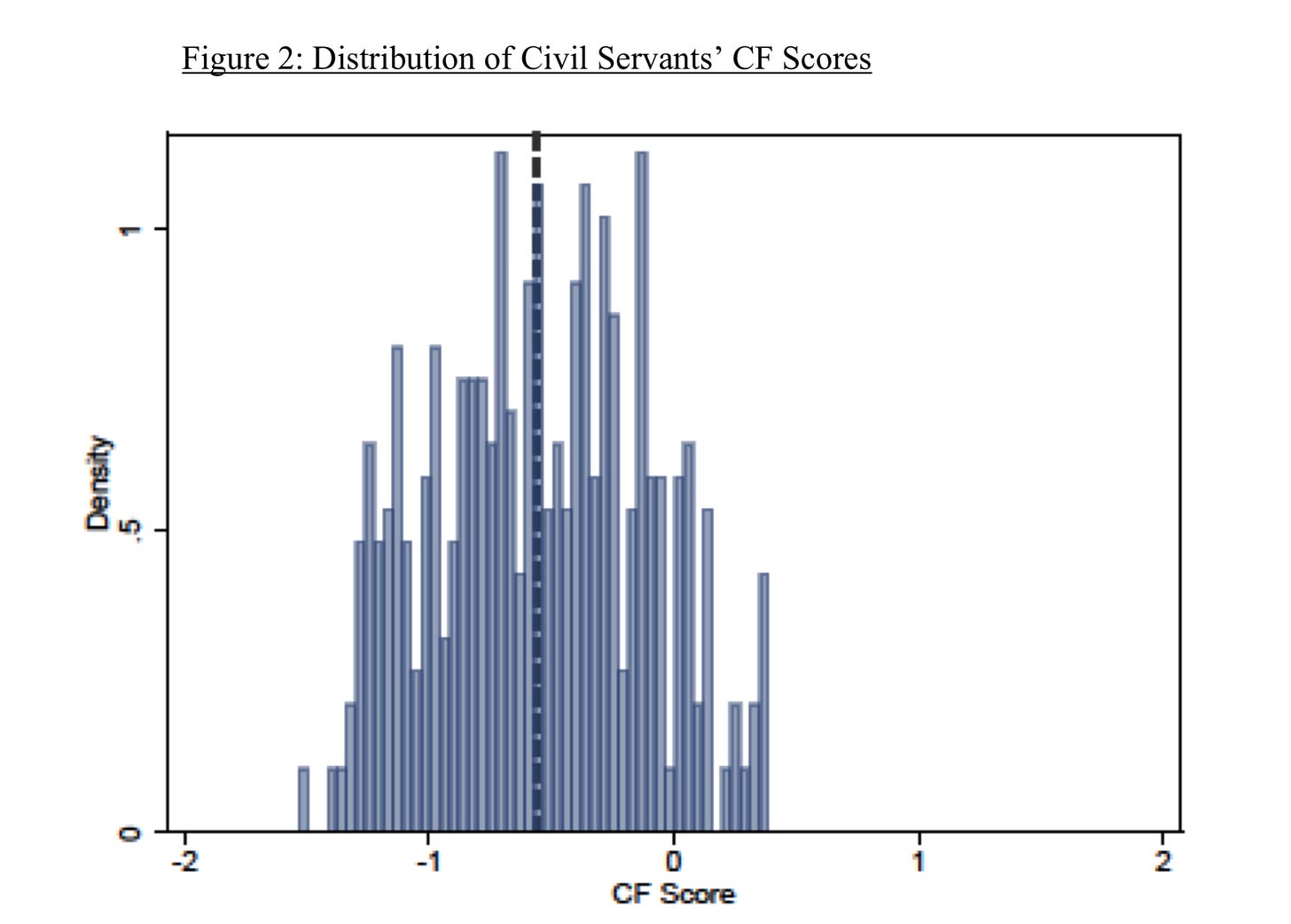

Based on donation records, a new paper by Brian Feinstein and Abby K. Wood illustrates that political appointees tend to be more be found at ideological extremes, while career officials tend to be more moderate.

Thus, politicization is an especially bad idea if we want some continuity and moderation in policy implementation, rather than massive ideological battles every time a new President arrives.

Politicization increases anti-democratic risks

Thus far the arguments have been either managerial – how politicization relates to performance – or legalistic – how do we interpret the political power of executives. But the Trump era and the events of January 6th should compel us to broaden our view, to acknowledge that a competitive authoritarian regime is quite likely in the near future, and prepare accordingly.

In short, those concerned with protecting US democracy should also want to protect the career public service.

Public officials with career protections are more likely to follow their oath to uphold the constitution, accept democratic values like transparency, and ensure that statutory goals are implemented. Public officials selected because of loyalty to a particular leader are less likely to do so. Bureaucrats can oppose, undermine or shine a light on the sort of legal and norm-based violations that come with a shift toward authoritarianism.

Again, we saw examples of this during the Trump administration. Most obviously, and disturbingly, military leaders saw a coup as a real enough possibility that they discussed it, with the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff reportedly saying “You can't do this without the military. You can't do this without the CIA and the FBI…We're the guys with the guns.” While the military was preparing to resist a coup, some Trump appointees were trying to move it along, in ways that we are still learning about.

In less dramatic ways, career officials drew attention to a wide range of misdeeds during the Trump administration. Let’s go back to Trump’s first impeachment. Political appointees like Vought oversaw an illegal effort to withhold Congressional funding to Ukraine to gain political leverage. They offered a secret legal justification that once more drew on the unitary executive theory, holding that the President could break the law in cases when national security is at risk.

Career officials at OMB and the Department of Defense warned their political counterparts that withholding the funds was illegal, at odds with the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act of 1974, and a Supreme Court decision, Train v. City of New York 1975. Some of these officials resigned in protest. Ultimately a career intelligence official used legal whistleblower channels to raise concerns with an Inspector General. Some career officials also broke Trump’s attempt to stonewall Congress.

After his first impeachment trial Trump did all he could to name, harass and punish those individuals. The Department of Defense finance official who had raised concerns saw her nomination to a senior position pulled. A White House military official who testified was removed from his position. The Inspector General who had informed Congress of the whistleblower complaint was fired. Schedule F powers would have allowed an unscrupulous President like Trump to more easily put proverbial heads on pikes as a warning to anyone who would resist his illegal actions.

Trump could have avoided impeachment by listening to his career officials. When he didn’t, they helped to reveal presidential wrongdoing to Congress and the public. By contrast, Trump loyalists enabled corrupt and illegal actions, covered it up, refused to answer Congressional questions, and then participated in exacting Trump’s revenge against those who actually kept their oath to the constitution.

Should Trump return, so too would the authoritarian pattern of using of state resources to reward or punish political opponents – holding back federal aid, providing material support to political campaigns, or encouraging legal investigations of political opponents. Schedule F would place the administrative state more firmly under his thumb, giving Trump would a smoother path toward competitive authoritarianism.

The anti-democratic dangers of the unitary executive theory and its applications have been largely ignored by its advocates in the Federalist Society and the courts. The dominance of the President in this theory leaves little room for other sources of democratic accountability – such as accountability to Congress or the public – or the possibility that the President would himself threaten public values. It is perhaps no coincidence that John Eastman, an architect of Trump’s legal justification to overturn the election is another advocate of the unitary executive theory, claiming impeachment is the only basis to remedy Presidential misbehavior, even as the unitary executive theory gives the President the means to cover up his crimes.

Where do we go from here?

One obvious solution to these problems is to simply reduce the number of political appointees. This is not a new idea. In 1989, Paul Volcker’s commission on the future of the public service called for exactly this. What happened since then? The number of appointees has grown from about 3,000 to 4,000. It turns out that both parties like having political appointment positions to reward supporters.

Congress needs to act. If Schedule F was an attempt to expand executive strength, it also revealed legislative weakness. As Congress fails to directly respond, there is little reason to believe that some version of Schedule F will not return. As such, Congress has a clear institutional incentive to revisit civil service reform, finding ways to address valid criticisms of inflexibility in hiring and firing, but also ensure personnel processes are firewalled from partisan control.

Unfortunately, these changes are unlikely to happen without mobilizing the public. People are rightly concerned with other anti-democratic practices that could lead to the subversion of elections. It’s easy to see the link between these actions and a weakened democracy. The link between a politicized public sector and creeping authoritarianism is less obvious. It is, however, very much on the agenda of those seeking to take control of the administrative state, which is why we should be worried.

This piece drew from a new paper published in Public Administration Review and you can find an open-access copy here