Why averting the shutdown matters to administrative capacity

Research shows that shutdowns undermine policy implementation, federal employee morale

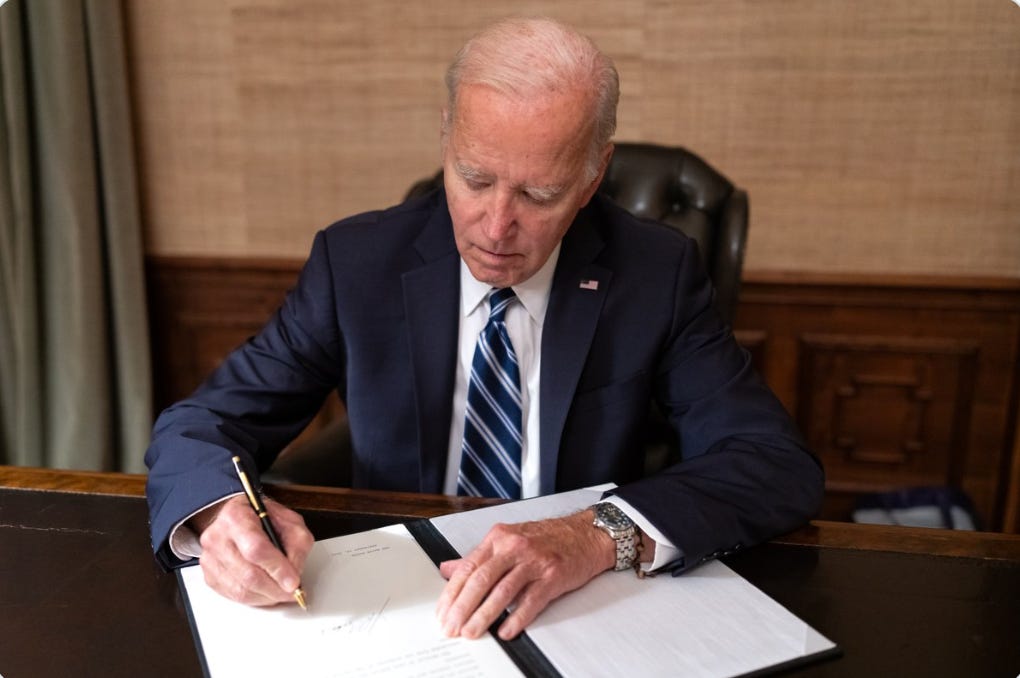

Shortly before the Saturday midnight deadline, President Biden signed a continuing resolution averting a government shutdown, at least for another 45 days. The outcome ended a dramatic day, when, after refusing to work with Democrats to avoid a shutdown, Speaker Kevin McCarthy finally did.

Peter Baker in the New York Times noted that most Americans did not seem all that engaged, reflecting a normalization of dysfunction. But in newly published research with Yongjin Ahn, in the journal Governance, we show that shutdowns really do matter, undermining the quality of public services in ways that are difficult to repair. Moreover, shutdowns diminish employee morale at a time of crisis for the federal workforce in terms of talent recruitment and retention. This quiet erosion of government capacity is the cost of political dysfunction.

Shutdowns are both distinctly American and modern phenomena. Other countries do not routinely stop providing public services when their politicians cannot produce a budget. Indeed, in parliamentary systems, a failure to pass a budget will often trigger a general election, a strong incentive for legislators to pay the bills. For most of US history, budget disagreements did not lead to shutdowns. Then President Carter’s Attorney General, Benjamin Civiletti, decided that they did. At the time, government leaders labeled the opinion “idiotic” and “absurd” and Civiletti later admitted he never imagined the ways in which it would pave the way for today’s version of the shutdown as a form of political warfare.

Federal government shutdowns are increasingly frequent and severe. The first four occurred under President Reagan, but none lasted for more than a day. Under George H.W. Bush, a three-day shutdown occurred, but affected less than three thousand workers because it fell over a federal holiday weekend. President Clinton’s administration experienced two shutdowns: one for five days in 1995 and one for 21 days in 1995-1996. The 16-day shutdown in 2013 under President Obama came as a result of demands to reverse the Affordable Care Act from the Tea Party wing of the Republican Party. President Trump experienced two shutdowns, first in January of 2018 affecting all agencies during the 3-day deadlock, and then in December 2018 to January 2019, for 35 days, affecting some agencies.

Shutdowns are becoming more likely because many legislators on the right see no real cost to stopping government services that they do not believe in in the first place. As Freedom Caucus member Chip Roy put it: “I’m not worried about a fight over funding a government that most of the people I know can’t stand.” President Trump called for a shutdown, and his political supporters saw it as an opportunity to pursue their anti-statist doctrine.

Shutdowns may be the preferred outcome for those that despise the government, but they have real costs for the work of public organizations. Strategic plans have to be set aside, and programs delayed. Scientific agencies stop the flow of grants, time-dependent lab work may be abandoned. Parks employees are unable to protect against vandalism. Regulatory inspections are backlogged. IRS employees lose time to be retrained in tax code changes. Federal court proceedings are slowed. When the shutdown ends, the simple administrative hassles of catching up with emails, completing time cards, creating new passwords, or designing new contracts distract from core tasks. These implementation hurdles slow government activities, To give a sense of scale, the 2019 shutdown caused an estimated $18 billion delay in federal spending.

We documented these costs for those who see the effects of the shutdown more closely than anyone else, drawing on hundreds of thousands of survey responses from federal employees who lived through both the 2013 and 2018-2019 shutdowns. These responses allow us to examine how shutdowns affect both policy implementation processes and employee morale.

Our analysis takes advantage of the fact that during the 2019 shutdown some agencies had seen their appropriations bills passed and some had not. This allows us to compare the responses of employees who were directly affected by the shutdown to those that weren’t. We found that employees exposed to shutdowns were more likely to report administrative dysfunction reflected in unmanageable workloads, missed deadlines, projects that were abandoned or delayed, and time lost to restarting work. Employees working in shutdown agencies also reported a greater number of these negative outcomes. At the same time, because agencies partner across so many different policy domains, even agencies that were not shutdown suffered some implementation losses, albeit at a lower level to their shutdown peers.

When it comes to employee morale, we find that the 2013 shutdown had an acute and lasting negative effect. However, we do not find the same impact for the 2019 shutdown. We speculate that the 2013 shock provided agency personnel a basis for anticipating what the 2019 shutdown might entail. In other words, employees have come to internalize workplace instability as part of how America governs now. Other research shows that the 2019 shutdown also increased turnover in agencies that were shutdown relative to those that weren’t. And so, those who experienced the most negative morale effects may also have voted with their feet, their views no longer recorded by surveys.

At a time when the federal workforce is aging rapidly, talent needs are not adequately being addressed, overall morale is low, and employees face the threat of overt politicization of their workplace, the impact of yet another shutdown may be an inflection point for our civil service. Even a near miss can be costly. Federal workers spent much of last week preparing for a shutdown rather than focusing on their core tasks. They might ask themselves, not unreasonably, why they put up with this.

McCarthy’s willingness to look for a bipartisan solution, albeit belatedly, represents a welcome prioritization of stability over chaos in governing. Will it hold? Matt Gaetz has promised to lead an effort to remove McCarthy as Speaker. But other House Republicans are promising to try to expel Gaetz, nominally for his ongoing ethical problems, but really for his challenges to McCarthy. By the time the next shutdown deadline rolls around, it is likely that McCarthy will have either consolidated his position as Speaker, perhaps with some help from Democrats, or he will be gone.

Shutdowns, like debt-ceiling crises, are a self-inflicted and unnecessary wound on American governance. They empower radical politicians who do not have popular support to pass their anti-government views, but can still exert a veto on the budget process. The resulting disruption and delay undermines the quality of government services that we all rely on.

William Resh is C.C. Crawford Professor in Management and Performance and Associate Professor at the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy.

Great post explaining the larger issues involved in a shut-down. I am also appalled at the increasing chaos by Republicans in Congress who ignore democratic principles and use their "leverage" to force everyone else to adopt to what they want (Tuberville and others). This is not governing.