When Volatile Work Schedules Meet SNAP Work Requirements

New policies put low income workers in jeopardy of losing vital supports

A father of three works at a pizzeria where his schedule resembles a roller coaster: 40 hours one week, 48 hours the next, then plummeting to just eight hours before rising to 24.

Under new work requirements for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly called Food Stamps), the main US program that helps low-income families afford food, a slow month with this erratic scheduling could strip him and his family of vital assistance. That’s despite this dad averaging 32 hours of work per week—well above the 80-hour monthly minimum the law will soon require.

Proponents of this new policy–a part of July’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act that is scheduled to take effect in March 2026–say that this policy will encourage parents to do more to provide for their kids. But the dad working at the pizzeria is not lazy or unwilling to work. In fact, he is doing everything he can to work more hours, taking on extra last-minute shifts when offered. But sometimes his shifts are cancelled or he is sent home early when business is slow.

He is one of the parents in a study we have been conducting with over 1,000 service-worker parents, as part of our decade-long research collaboration on the realities of low-wage work and parenting in the 21st-century United States. His story reveals that today’s low-wage work environment is defined by extreme volatility that workers cannot control.

The low-wage labor market has fundamentally changed. With the decline of middle-skill jobs and the economic shift away from manufacturing, workers with low levels of formal education— especially parents—are now concentrated in the service sector.

Service sector jobs are volatile, with work schedules, like this dad’s, fluctuating in response to factors such as foot traffic, weather, local sporting events, and corporate profit targets. These unstable schedules are already hard on parents, worsening mental health and sleep quality. And the new SNAP requirements will amplify the harms of instability.

That’s because work requirements with a set monthly work-hour threshold are poorly matched to the reality of these jobs. They will penalize workers with demonstrated strong labor force attachment—that is, workers who meet that requirement on average across the year but who experience volatility in hours.

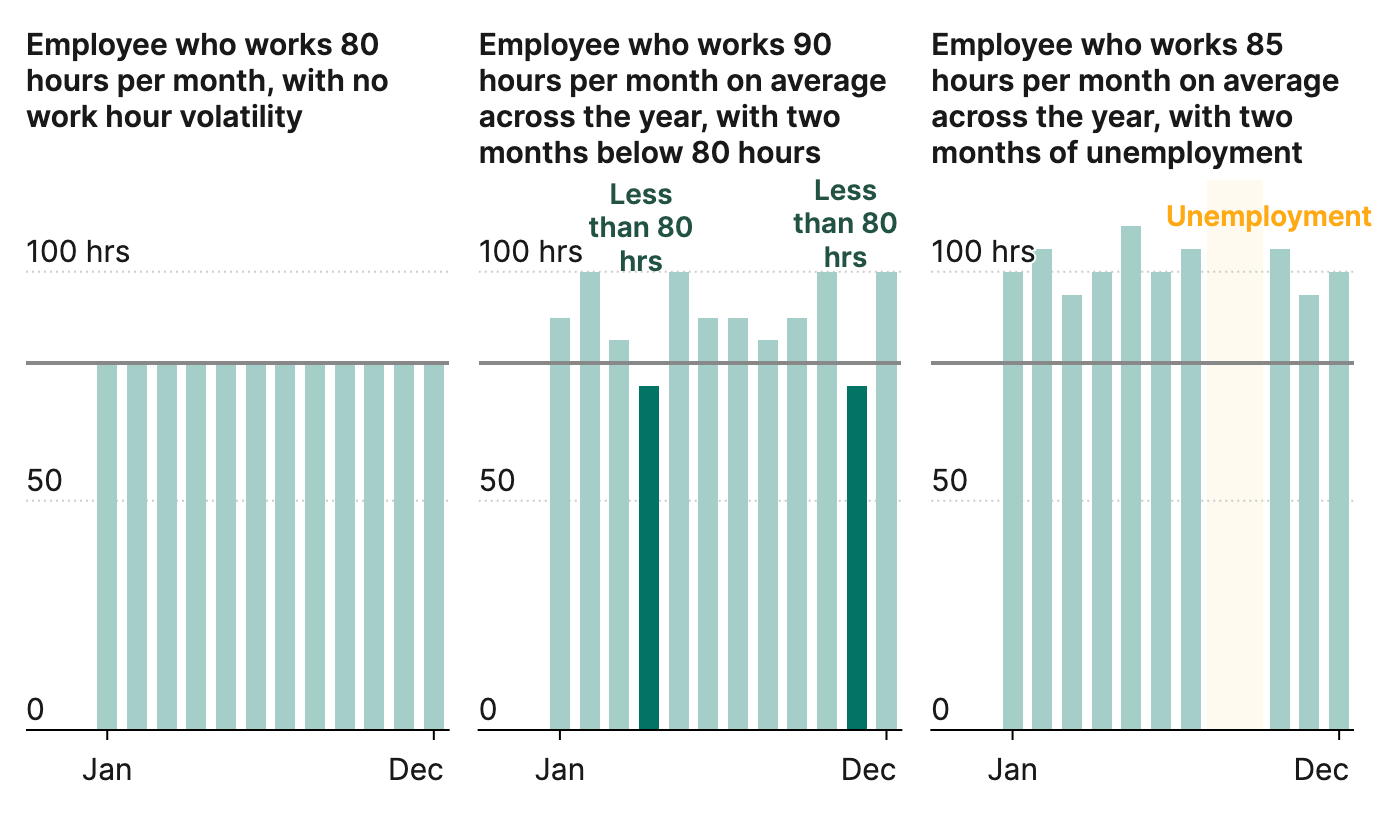

How could that happen? Figure 1 provides illustrative examples for how a person who meets a work requirement threshold on an annual basis could accrue penalties on a month-by-month basis, either by having a slow month at work (middle panel) or by losing their job and experiencing a period of unemployment (right panel).

Figure 1. Illustrative examples of how work volatility can cause a worker to fall short of a monthly SNAP work hours requirement

Our research with Olivia Howard using national data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation shows that such scenarios are common.

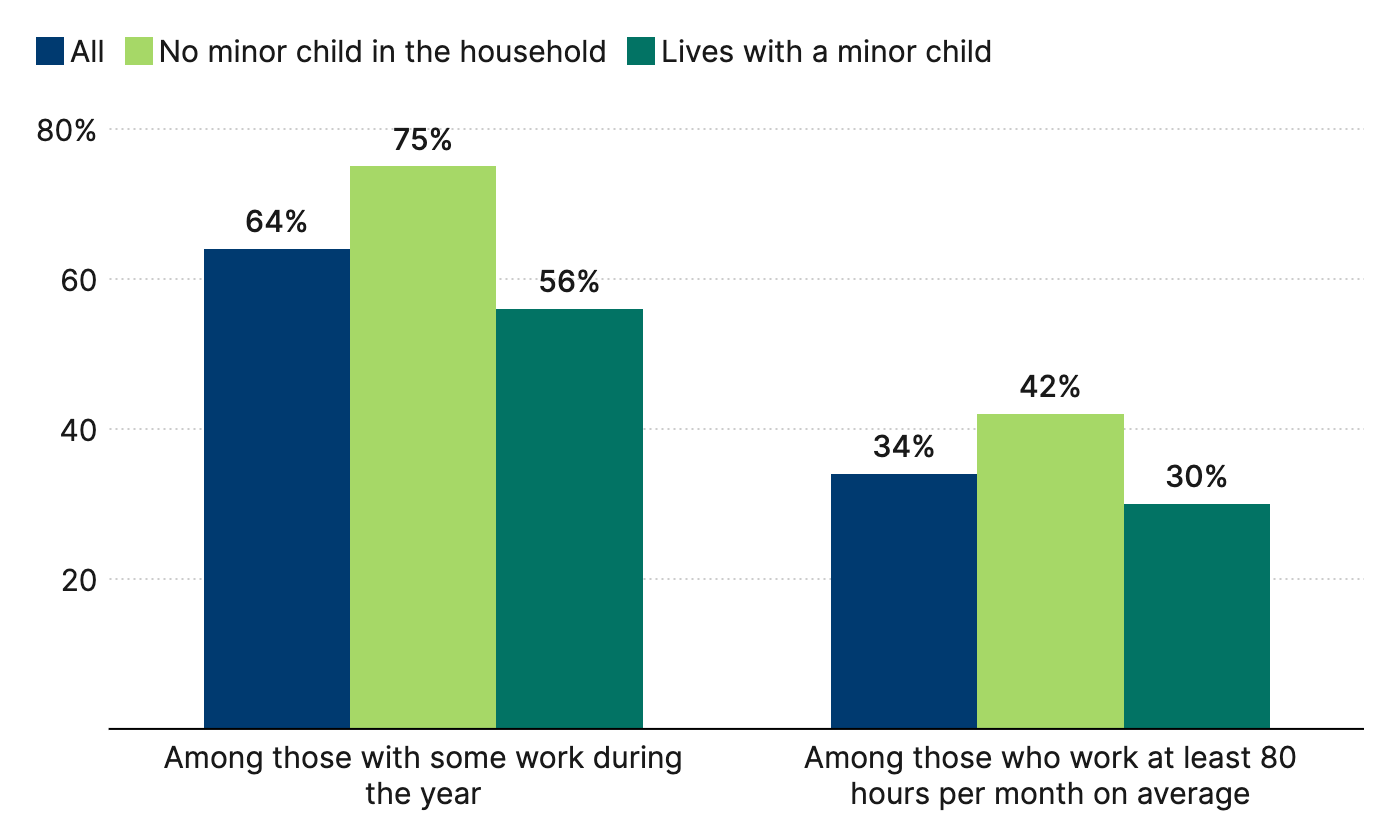

Many low-income service workers are already working more than 80 hours per month on average across the year. But, according to our calculations, one in three such workers nonetheless fall below an 80-hour-per-month threshold in at least one month in a year because of hours inconsistency or spells of unemployment (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Share of low-income service workers who worked 80 hours/month on average who worked less than 80 hours in at least one month, 2022

Hours volatility threatens workers’ ability to meet required thresholds even for those who are continuously employed. Our results show that even among those who both work 80 hours per month on an annualized basis and who avoid unemployment, 1 in 5 experience at least one month in which they work less than 80 hours.

But turnover is also high in the service industry: 41% percent of low-income service workers experience at least one month of unemployment during the year. Many such workers make up for bouts of unemployment by working well over 80 hours per month in the months when they have a job—so much so that their annual average monthly hours are above what the threshold would require, despite the time spent unemployed.

We find that nearly 1 in 6 low-income service workers who work at least 80 hours per month on an annualized basis would nonetheless fall short at least once in a year due to temporary unemployment.

Strikingly, these numbers come from data on workers’ experiences in 2022, a year with historic low unemployment and particularly strong demand for service sector work. It is likely that in a recession, even more workers with strong labor force attachment would, if facing monthly work hours requirements that ignore service-work volatility, lose food assistance.

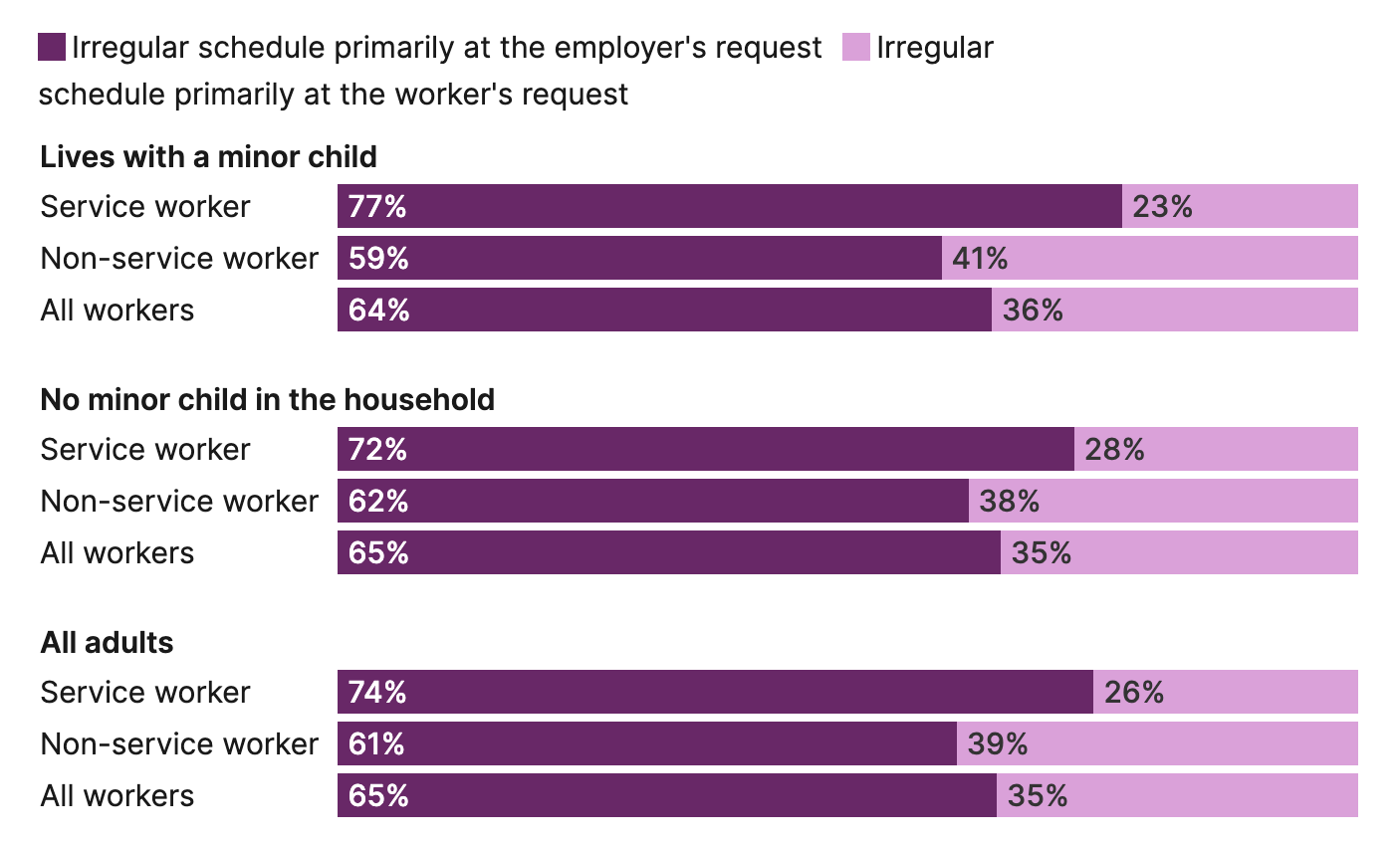

For some adults with care obligations, these months with lower hours could reflect a temporary need to cut back on work in order to focus on family responsibilities. However, the data show that overwhelmingly this volatility is driven by employers’ fluctuating needs, not workers’ preferences. Our analysis of the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) shows that some 65 percent of low-income workers with irregular schedules report that the irregularity is primarily at their employer’s request, including more than three-quarters of service workers in households with children (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Share of low-income employees with irregular schedules who report schedule irregularity is primarily at the employer’s request, 2023

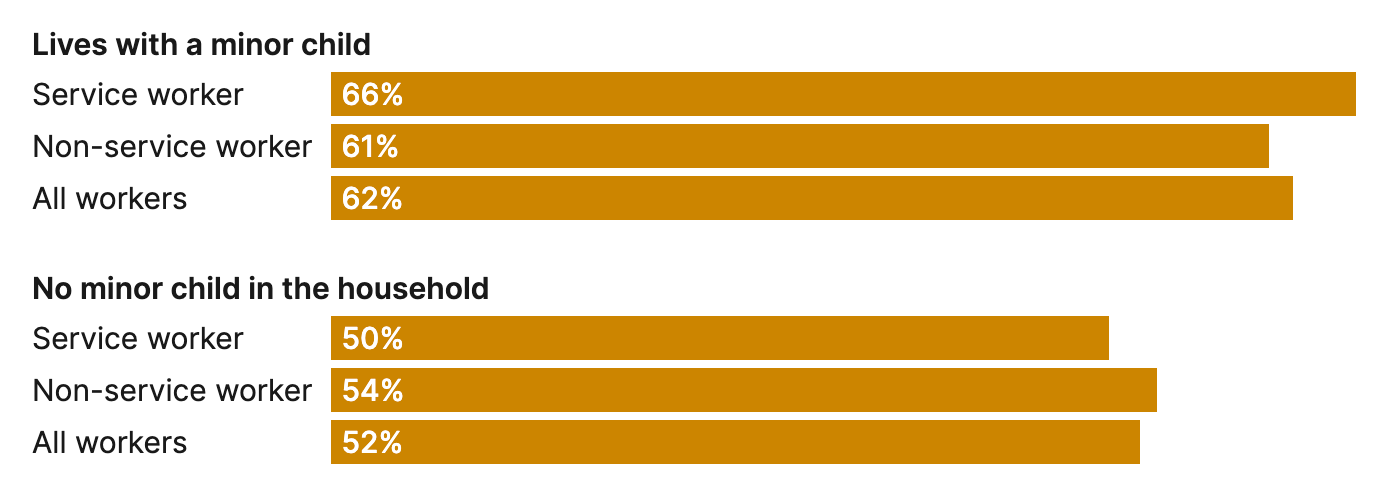

Our analysis of the SHED further shows that nationally, most low-income workers say they want more hours (Figure 4). This is even more true of low-income workers with children and especially of low-income service-worker parents: two-thirds of this particularly overstretched group say they want to work more but cannot get the hours.

Figure 4. Share of low-income employees who want to work more hours, 2023

Solving this problem is not as easy as just getting a second job: businesses in the service industry all want staff for the hours when customers want to shop and eat, meaning that many demand workers be available for the same set of times. Unlike during the heyday of manufacturing, there are very few “graveyard shifts” to be had.

Nonetheless, the heads of several federal agencies recently wrote that “if you want welfare and can work, you must.” What they are really saying is that “if you want food, you must work.” Yet research shows that they have it exactly backward. When people are—essentially randomly—either approved or denied for SNAP, workers who get access to SNAP work more over the next three years. Basic needs supports make the volatile, exhausting reality of low-wage work sustainable for families.

If policymakers who care about work were taking the long view, they would be especially cautious about restricting support for households with kids. Research shows that children who grow up with SNAP grow up to get more education, be healthier, and work and earn more.

In fact, every dollar spent on SNAP and other basic assistance programs has a return of nearly 10-to-1 on government investment, thanks to lower long-run health care costs, higher taxes paid, and less crime. That return is much higher than the “modest at best” return that researchers calculate we got from the 2017 tax cuts–the very cuts that policymakers have now slashed SNAP in order to extend.

These expanded work requirements will not save money or increase work in the long run, because workers can’t control their hours volatility–that’s an employer choice. If lawmakers really wanted to encourage steady work, they would be supporting Elizabeth Warren and Rosa DeLauro’s Schedules That Work Act, which would require employers to provide advanced notice and predictable schedules to their employees; evidence from localities that have passed similar laws shows that they improve worker well-being.

Stable schedules (which are relatively straightforward to implement using commonplace scheduling software) have even been shown to increase firm profits, by reducing worker turnover and increasing productivity–meaning that employers have every reason to decide on their own to shield workers from falling short of these work requirements by giving them stable schedules.

But the OBBBA’s work requirements don’t encourage, much less require, employers to do right by their employees. What they will do is punish workers–like the dad with his nose to the grindstone at the pizzeria–for labor market circumstances beyond their control.

Anna Gassman-Pines is Professor of Public Policy & Psychology and Neuroscience at the Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University. Elizabeth Ananat is the Mallya Professor of Women and Economics at Barnard College, Columbia University.

As a society, we need to stop punishing low-wage workers and start requiring employers to work with their employees. Employers sometimes use taxpayers to support their employees (SNAP, Medicaid, etc.) instead of accepting the responsibility for their employees without whom, they cannot operate.

Thanks for calling attention to this. Work requirements are not working. Workers need UBI yesterday.