What Does the Public Actually Think About the Access-Fraud Tradeoff?

Politicians are out of step with public views

A viral YouTube video posted by right-wing content creator Nick Shirley after Christmas claimed to expose massive fraud at Minneapolis daycares. Within days, the Trump administration froze federal daycare funding to Minnesota. And within two weeks, that freeze expanded to $10 billion across five Democratic-led states. Minnesota Governor Walz, as a consequence of the mounting pressure, dropped his reelection bid, and even Congressional hearings were convened.

However, there was just one problem. When Minnesota officials actually visited the nine daycare centers featured in the video, they found them “operating as expected”. Children were present. Services were being provided. It underlines that even though there were real problems with welfare fraud in Minnesota, much of the current policy response seems disproportionate.

The Trump administration’s justification for freezing billions in funding was straightforward: we need to prevent welfare fraud. Indeed, welfare fraud even served as one justification for the surge of immigration agents in Minnesota.

But that simple, yet effective, justification glosses over an uncomfortable truth. The proposed solutions to preventing fraud often make it harder for eligible families to access benefits. It means more documentation requirements, more verification steps – basically more hoops to jump through. Some families who genuinely need help won’t make it through these administrative burdens.

This is the tradeoff that often complicates welfare programs: more burdens, less fraud. To be sure, there are exceptions: Social Security features both low burdens and low fraud. But the default instinct of policymakers, especially those who might already be skeptical of safety net programs, is to add burdens whenever stories of fraud emerge. Policymakers rarely acknowledge this tradeoff exists, let alone tell us how they are weighing it.

So we decided to ask a question that has been almost entirely absent from public debate: How does the public think about the fraud-burden tradeoff? In other words, how much fraud are Americans willing to accept to ensure eligible people aren’t’ shut out?

The Tradeoff Nobody Talks About

Every welfare program faces a potential tension. Strict verification requirements help prevent fraud, but they also create barriers that keep eligible people from receiving benefits they are entitled to. This is what we call the access-fraud tradeoff.

Policymakers frequently invoke the specter of fraud to justify complex applications, repeated recertification, and extensive documentation requirements. But this rhetoric embodies an implicit value judgement about whether it’s worse for an ineligible person to receive benefits or for an eligible person to be denied them.

Consider the actual numbers. In SNAP (food stamps), fraud rates are typically estimated at 1 percent, or less. Meanwhile, about 18 percent of eligible households don’t receive benefits. That’s roughly one in five eligible families going without assistance they qualify for. Is that the right ratio? That is up to policymakers, but maybe they should understand how voters think about this tradeoff.

So we ran a national survey with 2,250 Americans to quantify the tradeoff people are actually willing to make. (Working paper here).

People Will Accept Some Fraud to Maintain Access

We asked respondents a straightforward question: Imagine reducing documentation requirements would allow 1,000 additional eligible people to receive benefits, but it would also let some ineligible people slip through. How many ineligible people would you accept?

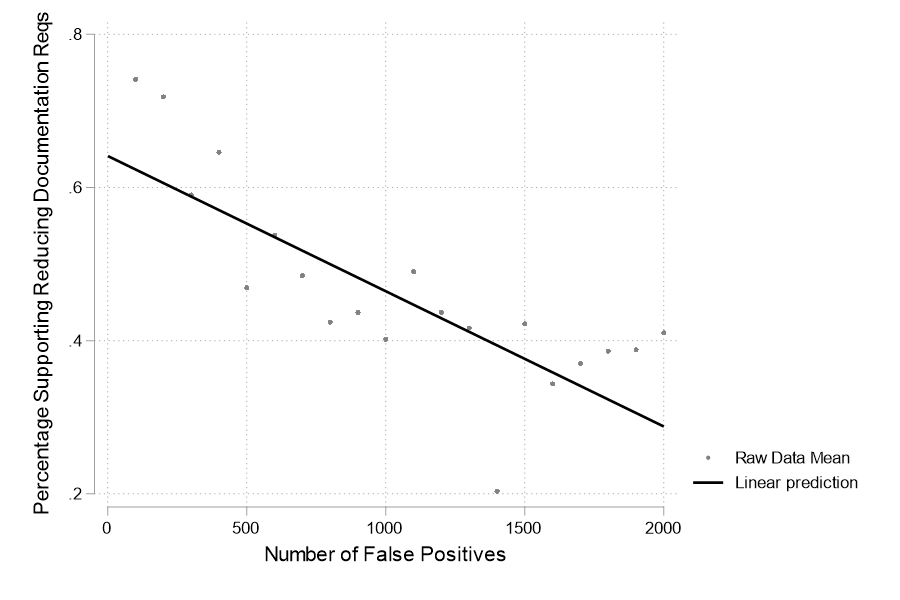

The answer surprised us. On average, respondents were willing to accept about 192 ineligible recipients to ensure 1,000 eligible people weren’t excluded. That’s roughly a 1-to-5 ratio. For every ineligible person who might wrongly receive benefits, Americans were willing to ensure five eligible people get help.

What does this mean? The public is far more willing to accept some fraud to maintain access than the current policy debates suggest. When forced to make a tradeoff, they do not default to a zero tolerance approach towards fraud, but put a high premium on access.

But Here’s Where It Gets Interesting

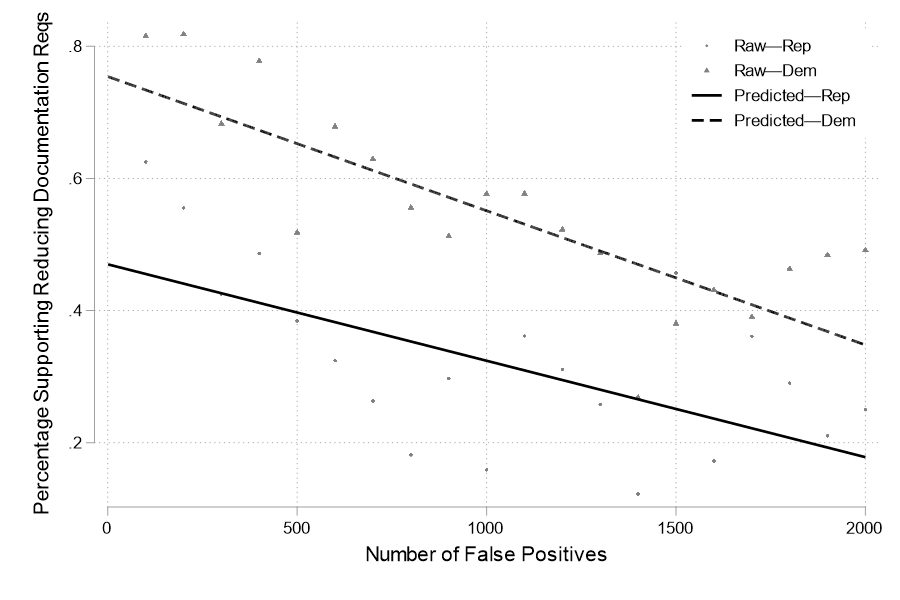

Political affiliation matters enormously. In general, Republicans are more opposed to welfare programs, and Republican politicians are more likely to rely on explicit messaging about fraud. As you might expect, Republican voters are generally less willing to trade access to welfare programs in return for minimizing fraud.

But political affiliation operates in some unexpected ways.

We randomly assigned respondents to evaluate either generic “welfare” or specific programs like SNAP or unemployment insurance. Democrats and Independents showed consistent preferences regardless of how we described the program.

Republicans, however, were different. When evaluating “welfare”, Republicans were willing to accept only about 3 ineligible recipients per 1,000 eligible ones. In other words, they were very intolerant of fraud and willing to add more burdens when welfare was an abstract concept. But when evaluating specific programs like “unemployment insurance”, that number jumped to 107. For SNAP, that number jumped to 16.

That’s a 5-to-35-fold difference purely based on how you describe the program.

This pattern aligns with decades of research of how the term “welfare” activates stereotypes. Ronald Reagan’s “welfare queen” rhetoric didn’t disappear. It embedded itself in how some Americans process information about government assistance. When they hear “welfare”, they automatically think fraud. But when they hear about specific programs with a defined purpose, they may be more likely to think about the actual beneficiaries. Once we get into the specifics of tradeoffs, Republicans are more willing to maintain access even if it means more fraud.

What This Means for Minnesota and Beyond

The Minnesota situation illustrates this dynamic perfectly. Before Shirley’s intervention, state and federal investigations of real fraud were proceeding. Then a Youtuber’s unverified claims about “welfare fraud” triggered a cascade of federal action that threatens childcare access for hundreds of thousands of families across multiple states. The administration justified cutting billions in funding by invoking fraud concerns.

Our research suggests this response is out of step with what Americans actually want. Even among Republicans, tolerance for potential fraud increases dramatically when the conversation shifts from abstract “welfare” to concrete programs serving people they deem “deserving”.

Policymakers should take note. The public is broadly supportive of access for services, even if it means some fraud. Democrats and Republicans might view our findings differently. Those who want to build support for maintaining or expanding access to social programs should talk about specific programs and their beneficiaries, and emphasize the cost of adding more burdens. Those who want to justify cutting access, keep the conversation focused on fraud, not tradeoffs, and abstract when it comes to program effects.

The Minnesota fraud scandals are real. The Feeding Our Future scheme defrauded taxpayers of $250 million. People should face justice for that. But the policy response we’re seeing goes far beyond prosecuting actual fraud. It uses fraud rhetoric to justify restricting access for millions of eligible families.

Our findings suggest that’s not what Americans want. When forced to make the tradeoff explicit, people across the political spectrum show meaningful willingness to accept some risk of fraud to ensure eligible families get help.

Maybe it’s time our policies reflect that.

Sebastian Jilke is an Associate Professor at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Georgetown University and Co-Director of the Better Government Lab.

Elizabeth Bell is an Assistant Professor at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin.

Fascinating, but not surprising. The word "welfare" has long been demonized by Republicans and people who believe the poor somehow deserve their fate. We also see that same sort of reaction to Obamacare versus the ACA or whatever state name is attached to health care plans. Words always have meaning and I agree that politicians should be careful how they name and discuss social plans.