"Unelected Bureaucrats" Are More Accountable Than You Think

Democratic accountability takes many forms other than elections

“Bureaucrats” is often sneeringly used as an insult rather than a descriptor, but apparently that is not enough. Adding “unelected” sweetens the attack.

Trump’s impeachment defense attacked “unelected bureaucrats” who dared to offer evidence to Congress. Criticism took off the pandemic. Ron DeSantis, for example, contending that “During COVID, unelected bureaucrats used ‘public health’ as a pretext to deprive citizens of their rights.” Trump has said that “Unelected, unaccountable bureaucrats must not be able to operate outside the democratic system of government.” The point is clear: “unelected” is a proxy for “unaccountable.” Accountability flows only from elections. Not elected, not accountable.

That’s not quite how the nation’s founders drew up the playbook. After all, they created a Supreme Court independent of the other institutions and of popular pressure, which made it the "least dangerous" branch of government, as Hamilton put it in Federalist 78. The court had "neither FORCE nor WILL, but merely judgment," and that gave it the political independence it needed. They certainly weren’t allergic to accountability, but they recognized that democracies depend upon different forms of accountability.

That cuts to the core of the problem. “Bureaucrat” is a universal term of disgust, and it has been for centuries. But it’s also clear from a June 2024 survey by Frank Luntz that about a third of all Americans, across the political spectrum, agree that government is “too politicized.” And by overwhelming majorities, supporters of both parties prefer a nonpartisan civil service to a politicized one. For example, 9 out of 10 people agree that the federal government is less effective when decisions are driven by politics, and 7 out of 10 believe that partisan politics makes government less effective. The public is not, in fact, calling for elected officials to play a bigger role in managing government, which is why the effort to delegitimate “unelected bureaucrats” is such a critical strategy for those that do.

The people who use the “unelected bureaucrat” sword typically point to the Constitution, which says that the president “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” The president is elected, has responsibility for executing the law, and therefore ought to control everyone who has a part in doing that–like government administrators. That closes the case for them.

But public servants are actually far more constrained by democratic values and processes than people realize, and perhaps even more than elected officials. Again and again, the public is told that unelected bureaucrats represent some sort of secret cabal, invisible to the public and intent on undoing a president’s policy. Or that it is impossible to fire public servants, which implies a lower level of accountability compared with private sector employees. But there are lots of different kinds of accountability layered into the system.

Accountability to Rules. There is a grain of truth to some of the criticisms. In the US, federal employees really do enjoy more job security than peers in private organizations. That’s on purpose. We had big problems in the 19th century where new administrations would sweep out the old employees and bring in new ones whose primary qualification was political loyalty, not competence. The government suffered mightily as a result.

Civil service systems are often described as a source of protection for federal employees, but they are also a source of constraint. They impose an extraordinary amount of rules about how employees should behave. The rules are there to reduce the risks of corruption, inappropriate political influence, or abuse of powers. The purpose of these constraints is to provide accountability. Lousy private organizations sometimes go out of business. Lousy public organizations do not, and end up making people’s lives worse off. And so we layer on a lot of rules and process to constrain how they act, or in more positive terms, to imbue democratic values into the public sector workplace, such as responsiveness, transparency, participation, due process, and equal treatment before the law.

Accountability to Performance: A legitimate concern is that the focus on rules precludes attention to performance. There might be no substitute for the bottom line of profitability, and the threat of going out of business, but agencies have to, by law, report their progress on specific performance metrics overseen by Congress. Another frequently articulated concern is that it is too hard to remove poor performers. Research by David Lewis shows that slightly less than half senior federal managers agree that it is possible to deal with poor performers, compared to one quarter of private sector executives. On the other hand, public managers were more confident that promotions were based on merit than their private sector peers, and more likely to recommend their organization as a place to work. The government’s turnover rate of 2.1 percent per year isn’t wildly different from similar private sector industries, like financial services, IT, and health care, especially after accounting for the government’s benefits which are designed to keep good employees around.

Accountability to the Public, part 1. While bureaucrats do not stand for elections, many have lots of ongoing, daily interactions with the public that they serve. These interactions create direct responsiveness to what the people want. Think about street-level bureaucrats like teachers, cops, and benefits counselors in Social Security field offices. Trust by vets in the care they get at the VA is 92 percent, far higher than at non-VA facilities. These close interactions force accountability that orders from the top never can.

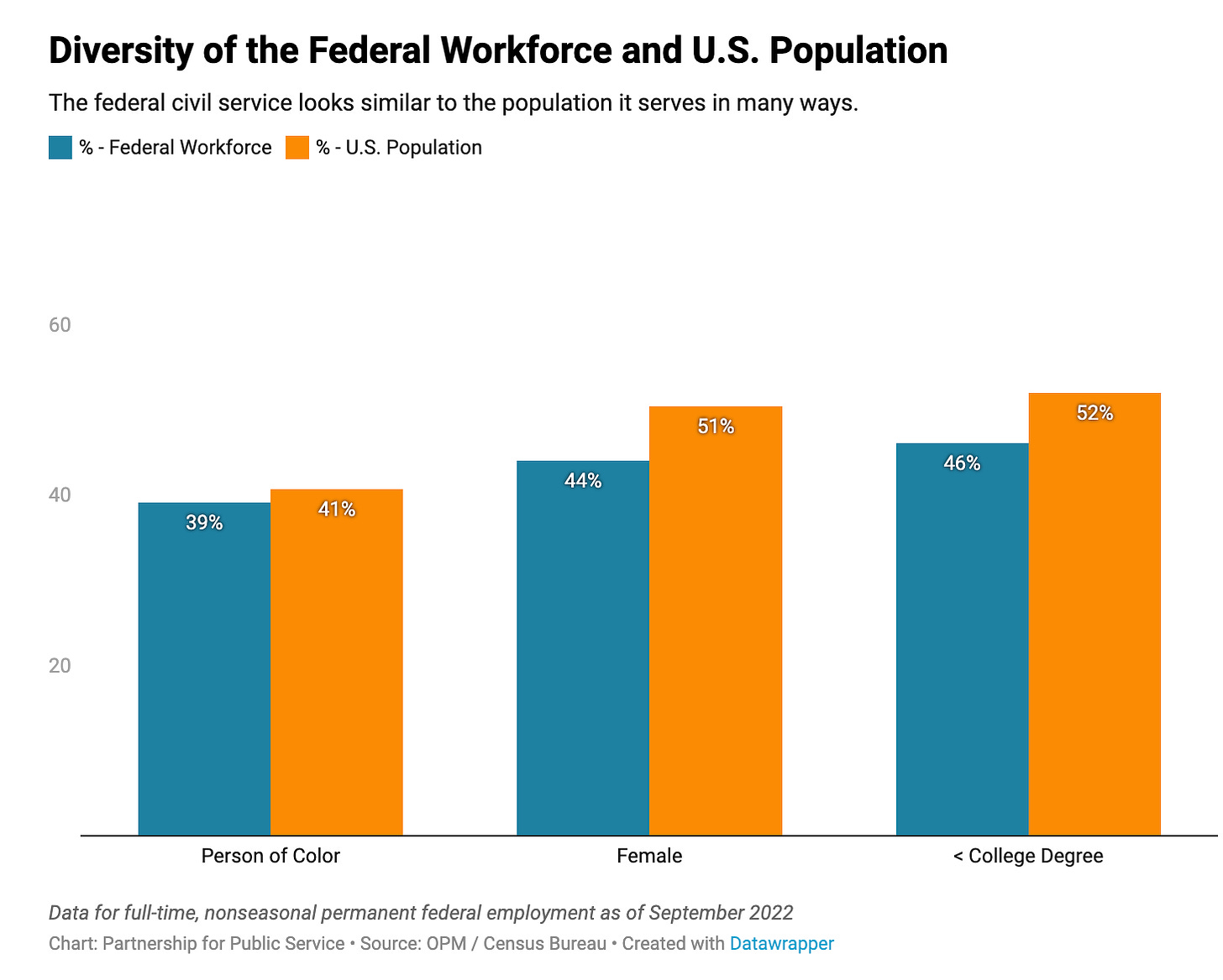

Accountability to the Public, part 2. Trump is pledging “to move parts of the federal bureaucracy outside of the Washington Swamp.” That, he said, would shrink the agencies and make them more accountable. But he’s pretty late to this idea. About 85 percent of all feds already work outside Washington. In fact, of the 10 states with the largest number of federal employees per capita, 7 went for Trump in the last election. They’re people that most Americans shop with, worship with, and stand next to on the soccer field. They are a relatively diverse bunch.

By contrast, the median net worth of members of Congress is over $1 million, and all necessarily work in DC. It is safe to say that while most public servants might not be perfectly representative of the public, they live a life that is a lot closer in terms of income and experience than the officials we elect to represent us.

Accountability to the Public, part 3: When Congress delegated authority to the executive branch to make rules, they also instituted democratic values into those processes. These include a requirement that draft rules must be posted for public comment, and that agencies have to read and respond to those comments. Final decisions are also subject to judicial review and can be overturned by Congress via the Congressional Review Act. This guarantees a seat at the table for the public, even if there are debates about how representative the process is. It also slows decisionmaking. Another critique of participation requirements is that it creates a vetocracy, where minority interests can use public input processes to slow or block progress in, for example, housing development.

Accountability to Congress and Oversight Tools. Then there’s the fact that government isn’t like a private company, where decisions flow from the top to people at the bottom in charge of carrying them out. The programs that government delivers, the structure of the agencies in charge of delivering them, the people who work in them, and the money they spend are all legislative decisions. The president can propose and negotiate, but he can’t unilaterally decide. He is not, in fact, a CEO. That means government employees always have to keep an eye on Congress and its expectations. And Congress is not shy about exerting that accountability.

Congressional oversight committees love to hold hearings about missteps. Congress has its own investigative arm, the Government Accountability Office. Congress also created a series of oversight tools. These include the positions of Inspectors Generals to seek out waste, fraud, and abuse, and whistleblower laws to report wrongdoing. As a public employee, your emails are subject to Freedom of Information Act requests. And if you do screw up, your actions are newsworthy, with the media or government critics looking for examples of failure.

Accountability to Professional Expertise. And, of course, administrators are hired because they’re supposed to be expert and accountable to the knowledge and standards of their profession. That might sound a little amorphous, but when you look at specific functions, it often means defending the integrity of evidence, science, and expertise even when it is not politically easy to do so.

For example, the former head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics warned how data could be imperiled if politicians seek to overturn professional standards to “speed up or delay release dates, add spin to release narratives, change methods arbitrarily or with political intention, replace career national statistical experts with unqualified candidates, grant early or special access to data for nonstatistical purposes, such as personal enrichment, political advantage, or enforcement activities.”

Another example: passengers on United Airlines can get a peek into air-traffic control by listening in on Channel 9 of their audio system. Listening into even a few seconds of communications around O’Hare on a snowy day is enough to convince even the most jaded taxpayers that they need the best experts possible. We’ve never heard anyone on final approach to the runway complain about “unelected bureaucrats.”

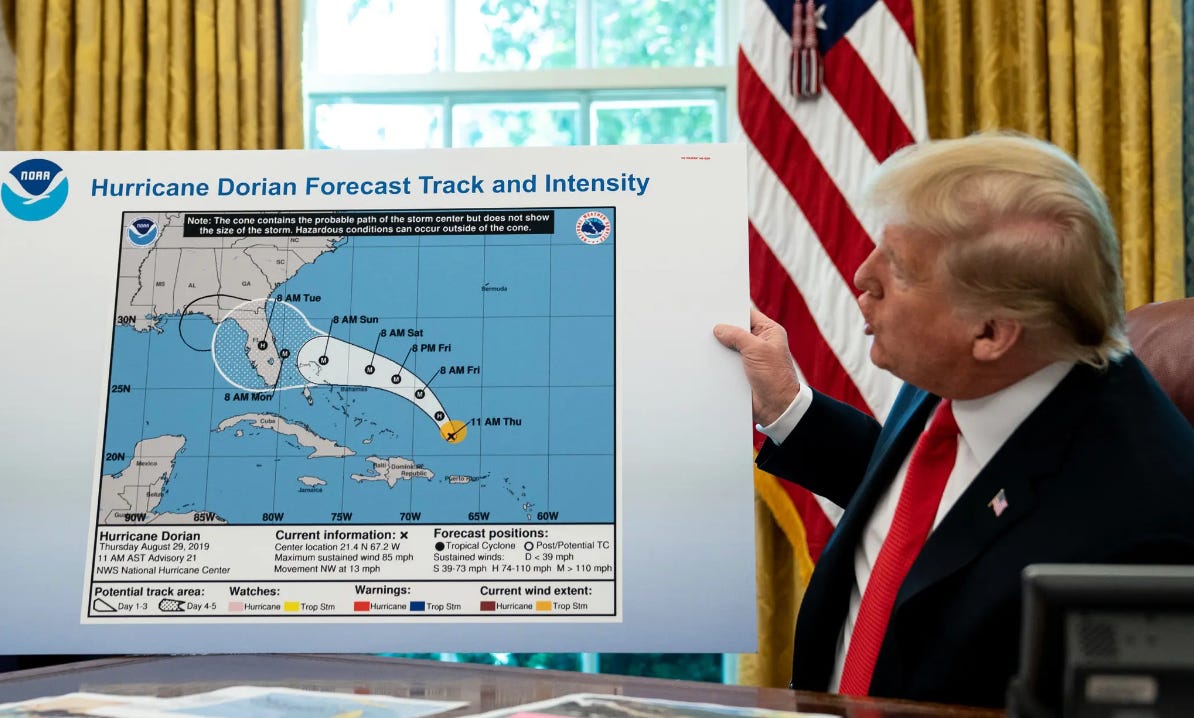

The forecasters in the National Hurricane Center have gotten really good at predicting the strength and impact of storms. The Center nailed both the power and landfall of Hurricane Milton days in advance. But the implications of imposing more political control over these “unelected bureaucrats” made headlines back in 2019’s “Sharpiegate” escapade, when Trump claimed that Hurricane Dorian was on track to affect Alabama, the local National Weather Service Office stuck to its forecast guns and said otherwise. Trump showed a “corrected” map with Alabama circled in with a Sharpie and department officials pressured the local forecasters to change their forecast to save the president more embarrassment. That kind of pressure to force forecasters away from their best scientific judgment undermined trust in the emergency warnings and created a “chilling effect on NWS forecasters’ future public safety messages,” as the Department of Commerce’s Inspector General later found in a report. Trying to leash scientists to the political needs of an administration, quite simply, can cost lives.

Taking Money: If you are an elected official, you can essentially accept unlimited bundles of campaign donation cash from stakeholders who are seeking to influence your decisions. Direct quid-pro-quos are illegal, but it's very difficult to prove such relationships and very easy to duck that proof. If you are a federal employee, in contrast, you cannot receive more than $20 in gifts from any source or $50 over the course of the year. At a time there is more and more money in politics, civil servants are sheltered from its influence in a fundamental way, able to make decisions without having to worry about satisfying donors.

Spending Money: Public employees are also significantly constrained in how they use resources. This is because misuse of public funds triggers scandal and blame. So, you can’t spend public money on resources that are inappropriate (like alcohol) even if your private sector peers can. For example, when the General Service Administration held an event in Las Vegas, it was national news. It felt inappropriate, but of course private companies bring employees to Vegas all the time. The upshot was that it became much harder for any federal employee to engage in travel for years. The perception of appropriate behavior was valued more than normal workforce development spending.

Typically federal employees have to get permission ahead of time for even minor spending, and they must have open competition for larger spending items, like hiring an employee or procuring goods and services. The sheer volume of administrative burden adds up, meaning that lots of public employees spend their time filling out forms. For outsiders, contracts are won not necessarily by the most qualified bidder, but by those best able to negotiate complex procurement processes.

Accountability to the Constitution. One of us once served as a real-life federal unelected bureaucrat–and still remembers the day swearing the oath that all unelected bureaucrats take: “I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States” and “I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter.” It was a deeply moving moment, as it is for all feds.

So we can always fight over whether federal government officials are sufficiently accountable to the policies of elected officials, but we can never forget that they’re responsible not only to the president but also to lots of other expectations as well – and that they rarely all align.

That’s worth thinking about the next time a TSA official screens your baggage or you see a television film about a Forest Service firefighter on the front line of a wildfire.

We don’t want to make the claim that there are not ways to improve the performance and accountability of public officials. Indeed, we have both made the case for government employees being more agile and able to pursue outcomes, which necessarily implies revisiting some of the rules and constraints they work under. In other words, it is possible that public servants are too accountable to too many rules, rules that were created via democratic processes to serve democratic values. These values are profoundly important, but create tradeoffs when it comes to delivering the services that the public cares about. But that's a different argument. For now, the next time you hear the claim that bureaucrats are not elected, don’t fall for the misleading implication that unelected means unaccountable.

If you found this post valuable, you might enjoy this series about the work of bureaucrats in government from the Washington Post.

Guest writer Don Kettl is professor emeritus and former dean at the University of Maryland School of Public Policy. He is the author of 25 books about American government, a senior adviser at the Volcker Alliance, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and a fellow of the National Academy of Public Administration.

Great insights supported by research and evidence

This is an important and timely article; thanks to both of you for working on and publishing it.