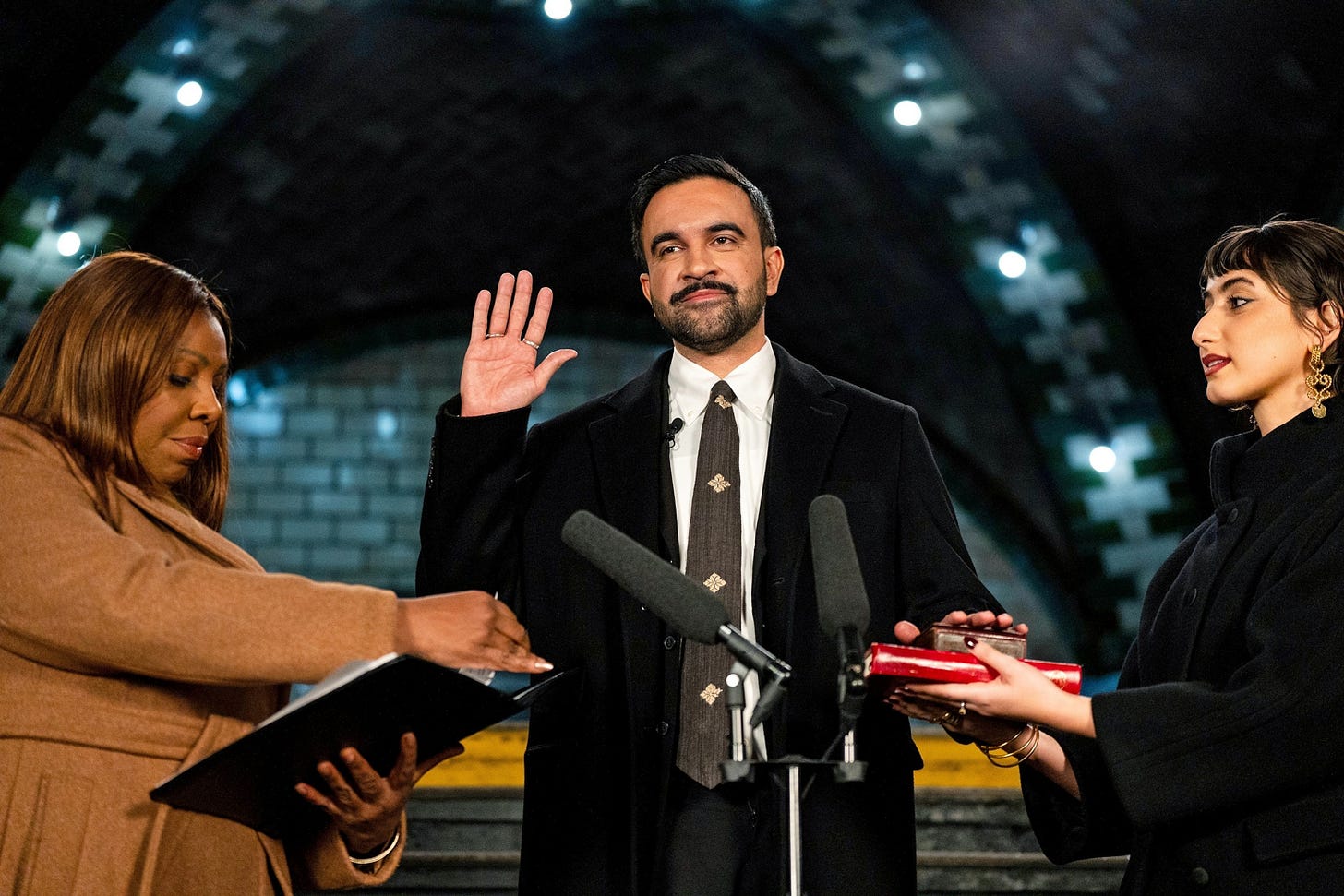

Understanding Mamdani's Vision

His inauguration speech challenges the left to govern

Whatever your views on Zohran Mamdani, it is worth paying attention to his inauguration speech. He is the first executive of a major American government in the long time to lay out a vision that is unapologetically and explicitly left-wing. He recognized the importance of presenting such a framework at a moment of extraordinary upheaval in American democracy:

What we achieve together will reach across the five boroughs and it will resonate far beyond. There are many who will be watching. They want to know if the left can govern. They want to know if the struggles that afflict them can be solved. They want to know if it is right to hope again.

As a pair of public policy professors, we identify the themes that jumped out to us.

The Dog that Didn’t Bark: Trump

Before we get into what Mamdani did talk about, its also worth noting what he didn’t talk about. A striking aspect of the speech was the relative inattention to Trump. The only time he named him was to welcome former Trump voters into his tent:

Few of these eight and a half million will fit into neat and easy boxes. Some will be voters from Hillside Avenue or Fordham Road who supported President Trump a year before they voted for me, tired of being failed by their party’s establishment.

Indeed, Mamdani reserved his harshest criticism for establishment moderates—both Democrat and Republican. Perhaps most striking, was this judgement:

For too long, those fluent in the good grammar of civility have deployed decorum to mask agendas of cruelty.

He goes on to point out that, New York City Hall has mostly belonged “only to the wealthy and well-connected, those who never strain to capture the attention of those in power.”

It’s Not Just about the Kitchen Table Issues

The popularist wing of the Democratic Party might applaud Mamdani’s willingness to welcome Trump voters. And while a superficial analysis might focus on Mamdani’s attention to kitchen table issues, this would fundamentally misunderstand his intent.

While Mamdani talked about affordability—freezing rents and making childcare and buses free—his broader point was to reclaim the meaning of freedom, and the responsibility of government to ensure that we have it.

These policies are not simply about the costs we make free, but the lives we fill with freedom. For too long in our city, freedom has belonged only to those who can afford to buy it. Our City Hall will change that. ... Here, where the language of the New Deal was born, we will return the vast resources of this city to the workers who call it home.

Anyone familiar with FDR’s Four Freedoms speech (or the Norman Rockwell paintings that followed) will recognize the lineage. Mamdani was calling for a modern version of the New Deal coalition, with the matching vision of a government willing and able to fight for the freedoms the New Deal promised.

The Era of Big Government is Not Over

Mamdani also made a point to explicitly reject the neoliberalism that has defined American politics—from Reagan to Clinton (and yes, even Obama).

To those who insist that the era of big government is over, hear me when I say this—no longer will City Hall hesitate to use its power to improve New Yorkers’ lives.

The “era of big government is over” is, of course, a defining line from Bill Clinton’s presidency, one delivered during his 1996 state of the union address. It signaled a seeming bipartisan concurrence around the idea that shrinking the size of government and allowing the private sector to step in to the greatest degree possible was in the best interests of all concerned.

Mamdani links third way centrism to a failed economic project—one that has accelerated income and wealth inequality as government faded into the background. He also sees the neoliberal era as a direct threat to democracy. He is arguing that democracy has been undermined not as much by a single individual (Trump), but by decades of policies that have led to an anemic government—one that has enriched those sitting atop the private sector and left everyone else treading water—and fueled distrust in the overall democratic project.

In his view, treating the state as just a safety net, there to step in when the market fails, is insufficient. Many lost faith because the government wasn’t actually working for them:

For too long, we have turned to the private sector for greatness, while accepting mediocrity from those who serve the public. I cannot blame anyone who has come to question the role of government, whose faith in democracy has been eroded by decades of apathy. We will restore that trust by walking a different path—one where government is no longer solely the final recourse for those struggling, one where excellence is no longer the exception.

The government that Mamdani envisions is one capable of doing big things. While Trump is transforming the federal government into a personalist vehicle of retribution and profit-taking, Mamdani is making the case that Americans remain capable of using their government to solve their shared problems.

I have been told that this is the occasion to reset expectations, that I should use this opportunity to encourage the people of New York to ask for little and expect even less. I will do no such thing. The only expectation I seek to reset is that of small expectations. Beginning today, we will govern expansively and audaciously. We may not always succeed. But never will we be accused of lacking the courage to try.

That final line echoes FDR’s explanation of his New Deal experimentation: “It is common sense to take a method and try it. If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

Taking Governance Seriously

The New Deal was a political and policy project, but it was also a period where the American elite took implementation seriously. Mamdani draws upon this aspect of the New Deal legacy in his inauguration speech.

It’s not just about policy. It’s about delivering those policies effectively. Here Mamdani also tags the latest iteration of progressive thought that has rediscovered implementation, which is Abundance, even as he makes it his own

City Hall will deliver an agenda of safety, affordability, and abundance—where government looks and lives like the people it represents, never flinches in the fight against corporate greed, and refuses to cower before challenges that others have deemed too complicated.

To set the standards for public sector excellence, Mamdani called on some familiar tropes of New York greatness:

We expect greatness from the cooks wielding a thousand spices, from those who stride out onto Broadway stages, from our starting point guard at Madison Square Garden. Let us demand the same from those who work in government. In a city where the mere names of our streets are associated with the innovation of the industries that call them home, we will make the words ‘City Hall’ synonymous with both resolve and results.

At a time when public servants are very much under attack, Mamdani does not reflexively defend government. Instead, he demands it to do better.

New Yorkers who will take on the bad landlords who mistreat their tenants and free small business owners from the shackles of bloated bureaucracy.

A Collective Vision of Citizenship

Central to Mamdani’s vision is that there is, contrary to Margaret Thatcher, such a thing as a society. He calls upon the idea of community, where we help one another, a contrast to the ideal of rugged individualism articulated by Herbert Hoover.

And if for too long these communities have existed as distinct from one another, we will draw this city closer together. We will replace the frigidity of rugged individualism with the warmth of collectivism. If our campaign demonstrated that the people of New York yearn for solidarity, then let this government foster it. Because no matter what you eat, what language you speak, how you pray, or where you come from—the words that most define us are the two we all share: New Yorkers.

This vision of citizenship is not passive. Mamdani asks the movement that brought him to office not to evaporate, but to stay with him when it comes to governing.

Before I end, I want to ask you, if you are able, whether you are here today or anywhere watching, to stand. I ask you to stand with us now, and every day that follows. City Hall will not be able to deliver on our own. And while we will encourage New Yorkers to demand more from those with the great privilege of serving them, we will encourage you to demand more of yourselves as well.

A Poem to New York and Its Diversity

Mamdani sketched the collective as connected by a single unifying identity—that of a New Yorker.

There is only New York, and there are only New Yorkers. Eight and a half million New Yorkers will speak this new era into existence. It will be loud. It will be different. It will feel like the New York we love.

That identity of New Yorkers is made up of a set disparate strands, tied together through diversity. Mamdani name-checked different neighborhoods, ethnicities, and religious beliefs.

They will be Russian Jewish immigrants in Brighton Beach, Italians in Rossville, and Irish families in Woodhaven—many of whom came here with nothing but a dream of a better life, a dream which has withered away. They will be young people in cramped Marble Hill apartments where the walls shake when the subway passes. They will be Black homeowners in St. Albans whose homes represent a physical testament to triumph over decades of lesser-paid labor and redlining. They will be Palestinian New Yorkers in Bay Ridge, who will no longer have to contend with a politics that speaks of universalism and then makes them the exception.

Mamdani recalled Mayor Dinkins description of New York as a “gorgeous mosaic.” He asked “Where else could a Muslim kid like me grow up eating bagels and lox every Sunday?”

This emphasis on New York’s diversity, represents, in miniature, the broader American creed of a nation of immigrants from different backgrounds connected by shared ideals. It represents an implicit contrast to the current White House’s insistence on an imagined history defined by White Christian Nationalism.

Mamdani’s poem to diversity also challenges some of his critics. For example, in a recent piece in the Claremont Review of Books, Christopher Caldwell, a New York Times Opinion contributor, described Mamdani as “almost comically foreign”, drawing parallels to President Obama. The explicit reasoning was bizarre—Mamdani “doesn’t swing his arm like a regular American.” (Do you swing your arms like an American? If so, please explain). He prefers soccer to baseball!

Mamdani wrote the kind of love letter to a American city that only someone deeply embedded in all of its richness could, a version of America that people like Caldwell will never experience or accept.

This is the city where I set landspeed records on my razor scooter at the age of 12. Quickest four blocks of my life. The city where I ate powdered donuts at halftime during AYSO soccer games and realized I probably wouldn’t be going pro, devoured too-big slices at Koronet Pizza, played cricket with my friends at Ferry Point Park, and took the 1 train to the BX10 only to still show up late to Bronx Science.

Mamdani’s inaugural may be truly important. There were also goofy and fun moments.

We can’t verify if for sure, but we are matching these words about Mayor Adams with this image.

He and I have had our share of disagreements, but I will always be touched that he chose me as the Mayoral candidate that he would most want to be trapped with on an elevator.

Many have pointed out the difficulty Mamdani will face when it comes to actually governing. And a fair criticism is that his inauguration speech leaned more heavily on poetry rather than the prose of governing. But Mamdani’s goal was not to lay out a bullet point list of policies. Instead, he offered a bold and contrasting vision of how a major city could be governed.

In practical terms, he will almost certainly fall short, but simply proposing a different way of thinking about governing offers a welcome broadening of the discourse around what is possible. As we watch the Republican Party accept authoritarianism and the Democratic Party struggle to articulate a compelling and contrasting vision, Mamdani will force a conversation among the left about how it should govern.

Well-said.

Caldwell: [Mamdani] “doesn’t swing his arm like a regular American.”

First they came for the people who don't swing their arm like a regular American, but I did not speak out, because I absolutely swing my arm like a regular American.

Or do I? Which arm is he talking about? Does it matter which? Are people judging me? Talking behind my back? Is that why Jones got the big promotion instead of me? Can I really say I love America when I just swing my arm (which one?!?) any old way without giving my technique any thought at all?

And that's what really worries me. I don't know if I'm a Heritage American, but I can pass for one (if you take my meaning). But what if my arms are giving me away? Am I on a list? Is subversive arm action a valid reason for a Kavanaugh stop?

Maybe I'm overthinking this. Maybe Caldwell is just a little bored of traditional racism, and wants to add some new folks to his list of irregular Americans. I think I'll go with that.

(But I'd still like to know which arm gives Mamdani away.)