The Lessons of Southlake

"Both siding" the Holocaust is the predictable result of a project to undermine the teaching profession

Sometimes you need to see a clear example of a system’s dysfunctions to truly understand its absurdities. Telling teachers they need to offer “both sides” on a contentious topic may sound ok in the abstract. But when they are struggling to find a balanced way to talk about the Holocaust, something has gone fundamentally wrong.

In offering guidance to teachers about a new Texas law that tells educators to “give deference to both sides” on controversial issues, a school leader emphasized the need for balance: “Just try to remember the concepts of [House Bill] 3979…and make sure that if you have a book on the Holocaust, that you have one that has an opposing, that has other perspectives.”

The story is here, which is part of an in-depth series by @Mike_Hixenbaugh and @ahylton26 which investigate how discussions of race have roiled Southlake school district. Lots of coverage of this broad topic have focused on viral school board meetings, or taken the perspective of the anti-CRT groups. By staying with a single district over time, Hixenbaugh and Hylton uses the tools of investigative journalism to explain in matter-of-fact terms how the anti-CRT movement is having a sustained and negative effect on the ability of local schools to function. While their reporting is excellent, I can add the perspective of someone who studies how public organizations work.

Big takeaway: Southlake is what you get when school officials are put under a never-ending outrage microscope

Southlake teachers are terrified and frustrated:

*One asks “How do you oppose the Holocaust?” “Believe me,” said the official, “That’s come up.”

*“Teachers are literally afraid that we’re going to be punished for having books in our classes. There are no children’s books that show the ‘opposing perspective’ of the Holocaust or the ‘opposing perspective’ of slavery. Are we supposed to get rid of all of the books on those subjects?”

“How am I supposed to know what 44 sets of parents find offensive? We’ve been told: ‘The parents are our clients. We have to do what they want.’ And this is what they want.”

*“They don’t understand what they have done. And they are going to lose incredible teachers, myself potentially being with them.”

Previously I wrote about how the anti-CRT movement is making the lives of teachers not just hard, but impossible. Southlake not just exemplifies this process, but illustrates the mechanisms. It might be an outlier, but sometimes outliers are instructive. Sometimes outliers tell us what the future looks like.

Why professional autonomy matters

Part of the function of bureaucracies, and bureaucratic leadership, is to convert irreconcilable or irrational goals into manageable processes. To do this, the best school leaders network with stakeholders, buffer the impacts of the political environment to moderate new demands or shocks like budget cuts, and provide an environment of stability for their staff.

There is a whole body of research, much of which is based on studies of schools in Texas, that shows that these factors – school autonomy, managerial networking, and stability – are associated with higher academic performance.

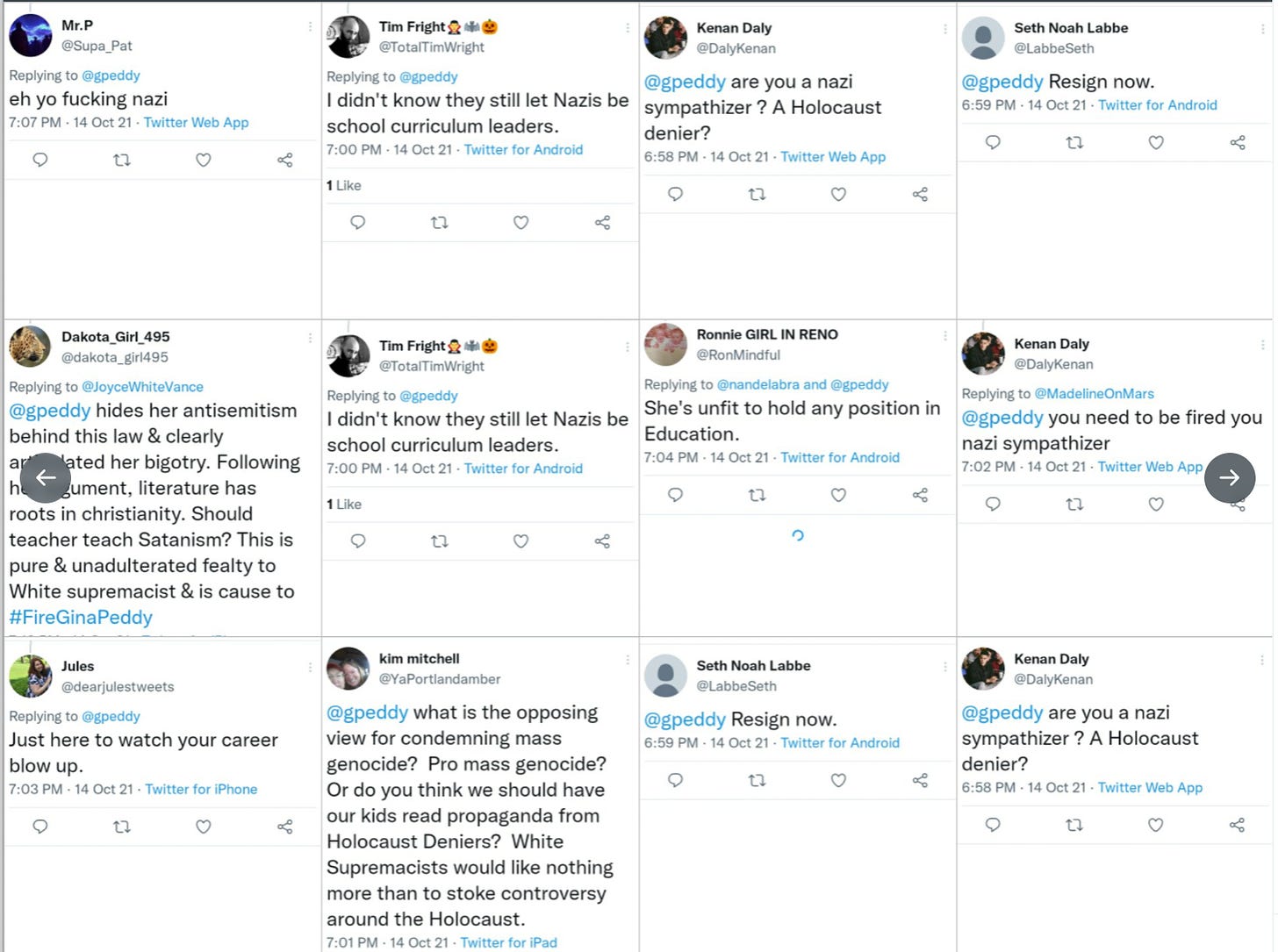

What we see in Southlake is the breakdown of these political-bureaucratic dynamics. School leaders feel unable to protect their teachers. Teachers see how exposed they are, and are fearful. The school leader who gave the Holocaust example acknowledged as much: “We are in the middle of a political mess. And you are in the middle of a political mess. And so we just have to do the best that we can.” When her quotes about went viral, some attacked and doxxed her, calling her a Nazi.

Such attacks miss the bigger picture. There is little point in berating either the teachers or school leaders for responding to their broader environment. Individual responses don't fix structural problems.

Indeed, some proponents of anti-CRT laws attacked the officials seeking to faithfully implement those same laws. For example, the New York Post has run so many anti-CRT stories that it has a dedicated section to the topic. They also ran a critical profile of the Southlake official for trying to implement the type of law that the New York Post has argued was necessary.

How school professionals respond reflects the local political environment

What are somewhat misleadingly labeled as anti-CRT policies are clearly more likely to be adopted in politically conservative communities. But public management research offers a more subtle point: the implementation of these policies also depends upon the local environment, and how much leeway stakeholders and local elected officials give to school officials.

Let’s say you are a principal in a liberal community in Texas. You are operating under the same state laws as peers in Southlake. But you might feel a little more emboldened to push back against the excesses of anti-CRT laws. You feel comfortable rejecting the absurd. There is no both sides to the Holocaust. You might allow classroom discussion and books that suggest that racial divisions have had enduring effects in American society. Some parents might criticize you, but you feel like the majority support you, as does your superintendent and the local school board. You can’t ignore the law, but there is a zone of discretion that lets you interpret it in ways consistent with the values of the local community and your professional training.

Let’s say you are a school leader or teacher in Southlake. It’s a very different story. Your political environment has shown you, repeatedly, that there is no zone of discretion. You will be punished unless you erase conflict about any topic that might impinge on white feelings. You have watched a video of your white students shouting the N-word at a party go viral. You saw the school district respond to student pressure to add diversity training. And then you saw a massive backlash. National conservative figures attacked the diversity training. A school board election resulted in a landslide victory for anti-CRT candidates, fueled by $200K in political donations.

$200K for a school board election in a Texas suburb.

That new school board chose to override the school district and punish a teacher. Why? She had a bestselling book in her classroom “This Book is Antiracist.” A student took it home. The contents upset the student’s parents, who complained. The teacher removed the book but the parents alleged the teacher was treating their student unfairly. Administrators cleared the teacher of wrongdoing. But the newly elected board, including candidates that the parents had donated $1,000 to, overrode the school district. A school board member warned:

“I would like to let the teachers know, if you are worried about teaching in this school district, that you should watch this vote. I want you to know that you are right to be worried.”

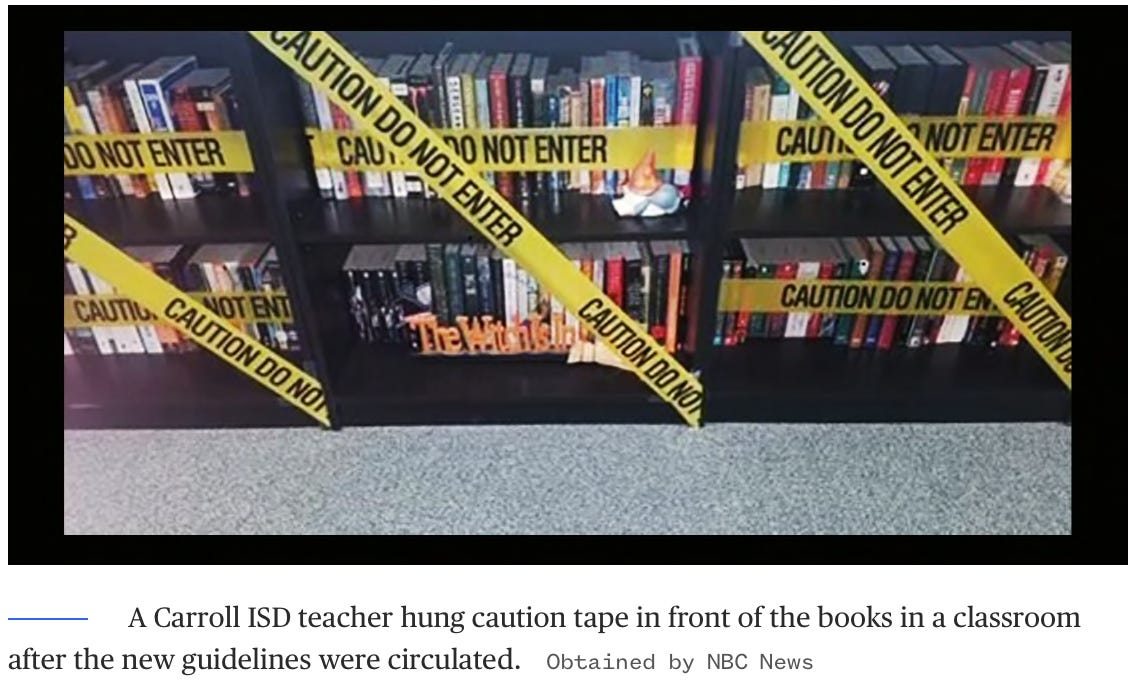

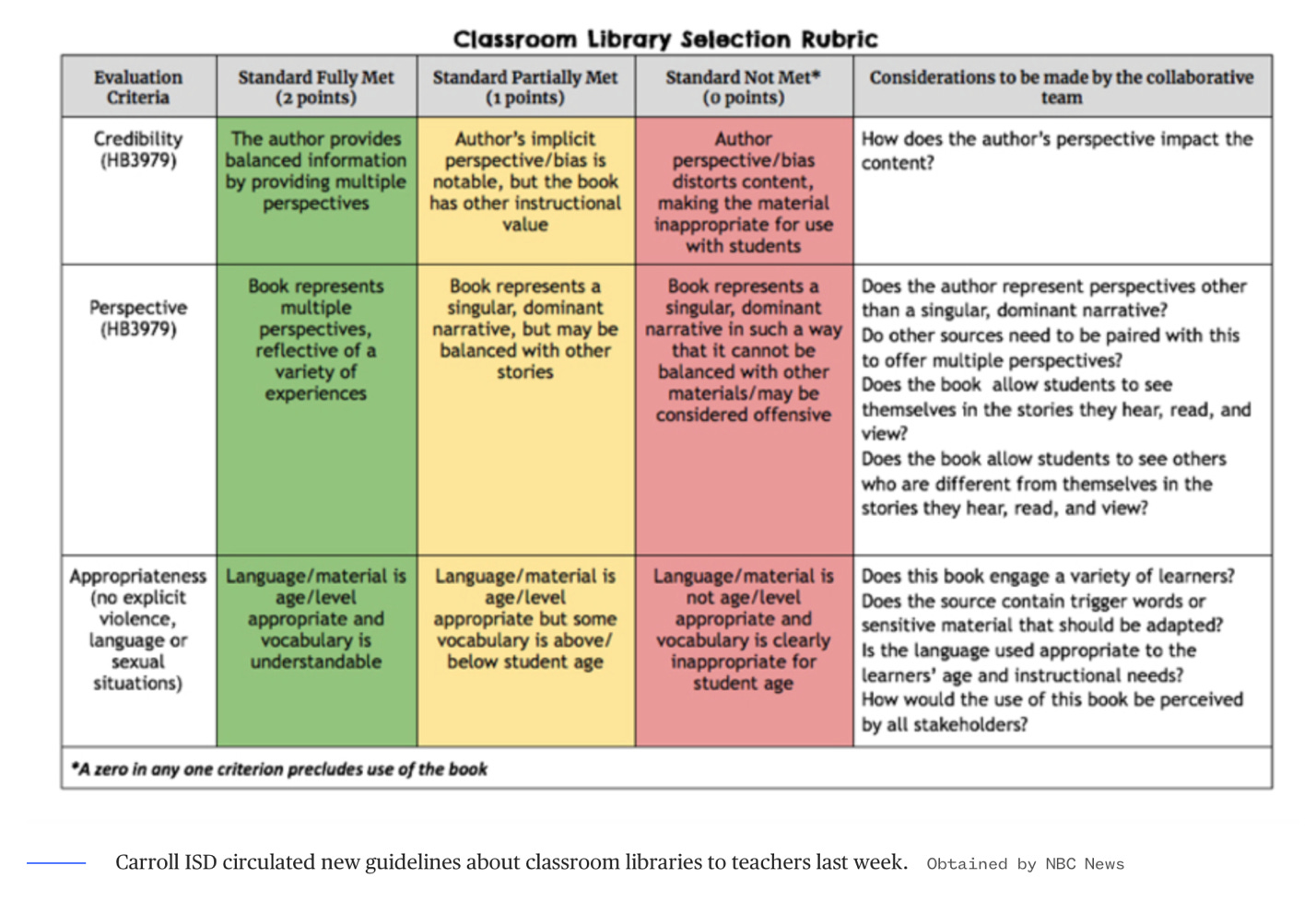

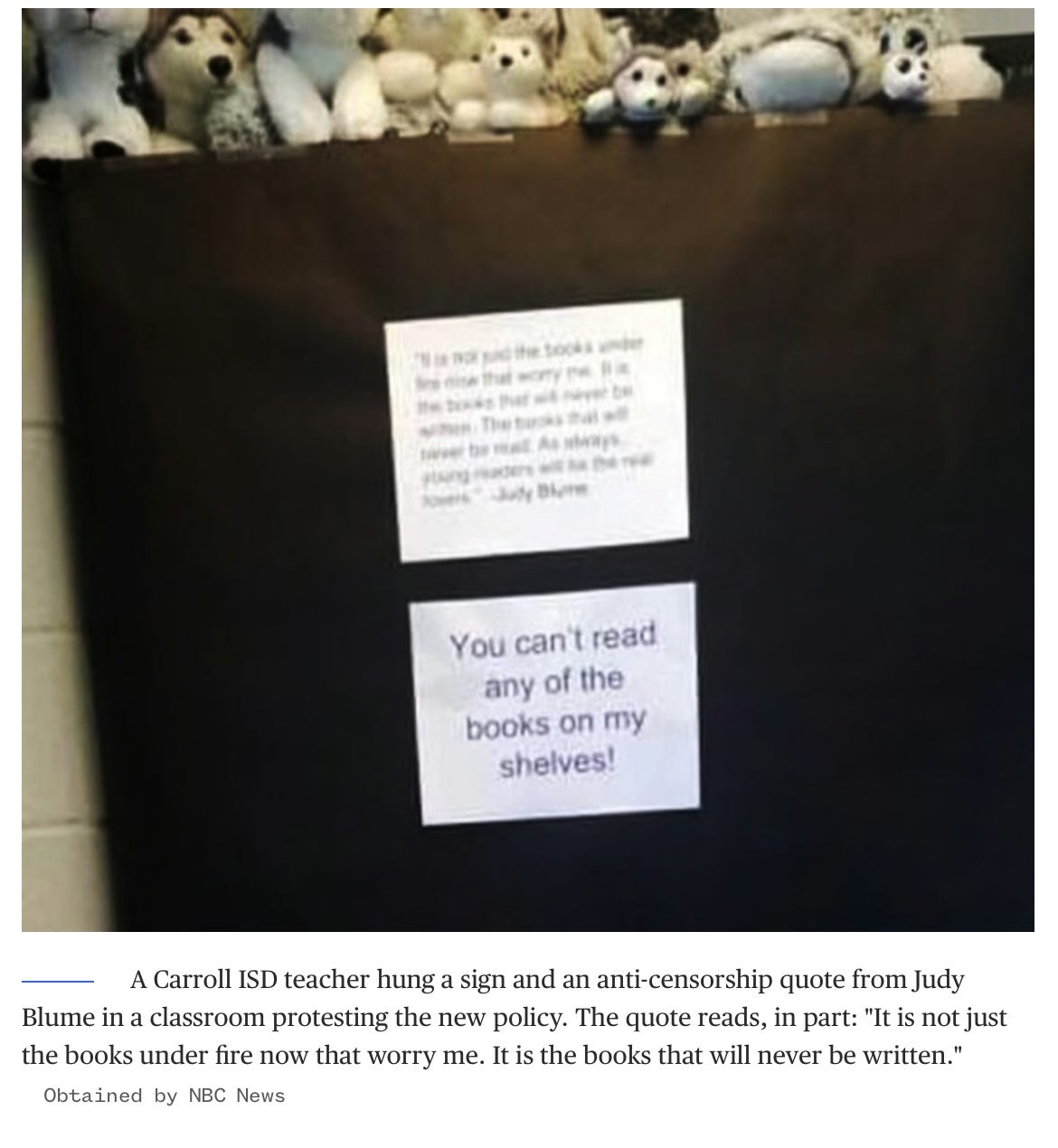

Southlake teachers were compelled to participate in mandatory training about which books are allowed in library classrooms, and which must be removed. The process was bureaucratic and perfectly rational, including a matrix to estimate the value of books to comply with a law that had already explicitly banned certain texts, such as the 1619 Project.

Advocates of the Texas law and similar anti-CRT policies will say this is not what the law intended. But in a fundamental way, what we see in Southlake is exactly the purpose of these laws: it is the diminution of expertise and autonomy in the teaching profession. It is the message that we are watching your every move, and will punish any betrayal of our orthodoxy. It is the instillation of fear to the point that teachers feel they cannot use their common sense to interpret how to apply the laws in their classroom and libraries.

Teachers are obviously upset in Southlake, but feel they have limited options in the short run. The long term effects will be to make places like Southlake less attractive for teachers, especially teachers of color who may feel most targeted by the environment.

The Holocaust example is instructive because it shows we have no such societal consensus about how we discuss other issues, most notably race. It is impractical to expect educators to be able to avoid the topic of race altogether. That would require them to ignore the history and present-day experience of America that their students exist in. It is no less absurd to rob them of professional discretion in managing these conversations, or to ask them to “both sides” right and wrong.

Teachers who feel terrified in the classroom cannot serve our students well. They cannot challenge the students to think critically about the world they live in. In the end, therefore, it is students who will bear the brunt of these policies.