The 2022 midterms were unusual in many respects: a long anticipated red-tide never emerged, the incumbent’s party did relatively well. Most hearteningly, voters largely rejected election deniers at the ballot box.

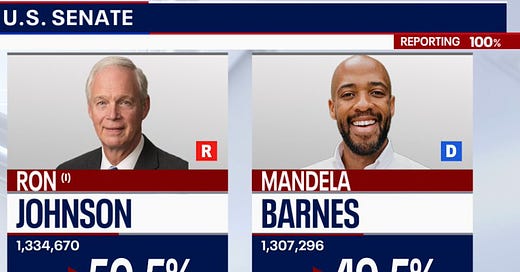

I want to focus on one particular Senate race to illustrate the banal and legal way that money and power matters in American elections. In Wisconsin, Ron Johnson, an undistinguished, unpopular two-term Senator who has lately become a conspiracy crank was narrowly re-elected, defeating Mandela Barnes.

One way of interpreting what happened is inefficiency of progressives in targeting of their funds.

The money mattered for sure. Many voters had no strong opinion of Barnes, and the spending framed him as soft on crime or different in ways that made the Wille Horton ad look genteel by comparison. Ads darkened his skin, portrayed him as “different” and superimposed his name on crime scenes. Exit polls showed that white voters, especially women, who supported the incumbent Democratic Governor switched their votes to Johnson for the Senate race.

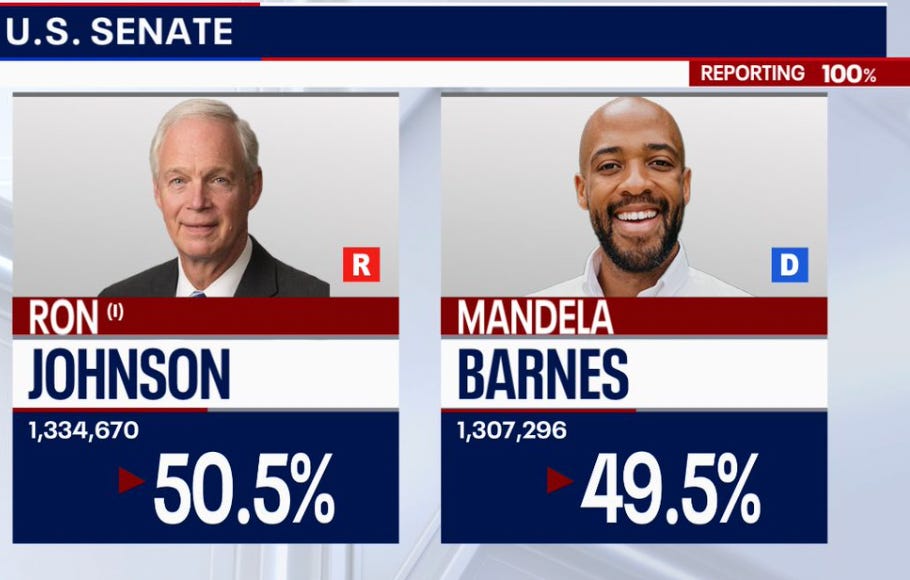

A new paper in the American Political Science Review emphasizes the power of money in elections, estimating that a $2 million advantage garners about 10k votes in a Senate race.

Barnes lost by less than 27,000 votes. Coincidentally, he was outspent by outside groups by about $27 million ($76 million vs. $49 million). If therefore seems reasonable to assume that spending difference gave Johnson the win.

One PAC, Wisconsin Truth Pac, spent $29M in the race, $9 million defending Johnson, $20 million attacking Barnes. In other words, one group provided the entire difference in outside spending.

The truth behind the Wisconsin Truth PAC

Ok, so money matters. But look deeper into the Wisconsin Truth Pac and a slightly different story emerges. This story is about not just the power of money, but of concentrated money, and how it can generate large returns.

Wisconsin Truth Pac is driven by three billionaires: Diane Hendricks, and Richard and Liz Uihlein. They have also spent smaller amounts on other pacs that also supported Johnson. Such concentrated support allowed Johnson the knowledge that he did not have to spend much of the campaign doing fundraisers, but could concentrate instead on actual campaigning and using conservative talk radio, and which he is much better at than being a Senator. [Full disclosure: I donated to Barnes for the reasons that should be apparent in this article, but have met Johnson, and found him personally engaging and confident, which are good qualities for retail politicking].

Why were the Uihleins and Hendricks so determined to save Johnson? No doubt there are surely shared ideological beliefs, but there is another more practical reason.

Tens of millions in donations, hundreds of millions in tax savings

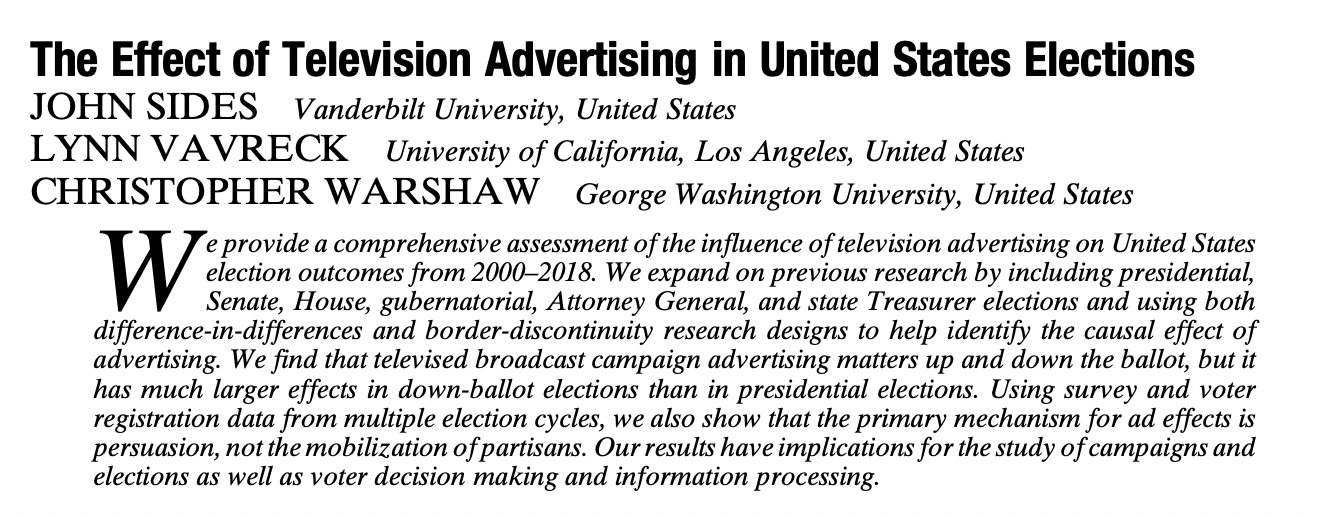

In 2017, when President Trump was pushing a large tax reduction, Johnson balked. This stance was puzzling, given that Johnson never met a tax cut he didn’t like. But he promised to vote against Trump and his party unless one particular loophole was in place. Here is how ProPublicia reported it:

Johnson’s demand was simple: In exchange for his vote, the bill must sweeten the tax break for a class of companies that are known as pass-throughs, since profits pass through to their owners. Johnson praised such companies as “engines of innovation.” Behind the scenes, the senator pressed top Treasury Department officials on the issue, emails and the officials’ calendars show.

Within two weeks, Johnson’s ultimatum produced results. Trump personally called the senator to beg for his support, and the bill’s authors fattened the tax cut for these businesses. Johnson flipped to a “yes” and claimed credit for the change. The bill passed.

It is important to provide context here: Johnson had just been re-elected after polling so dismally for much of the 2016 campaign that the GOP establishment had given up on him.

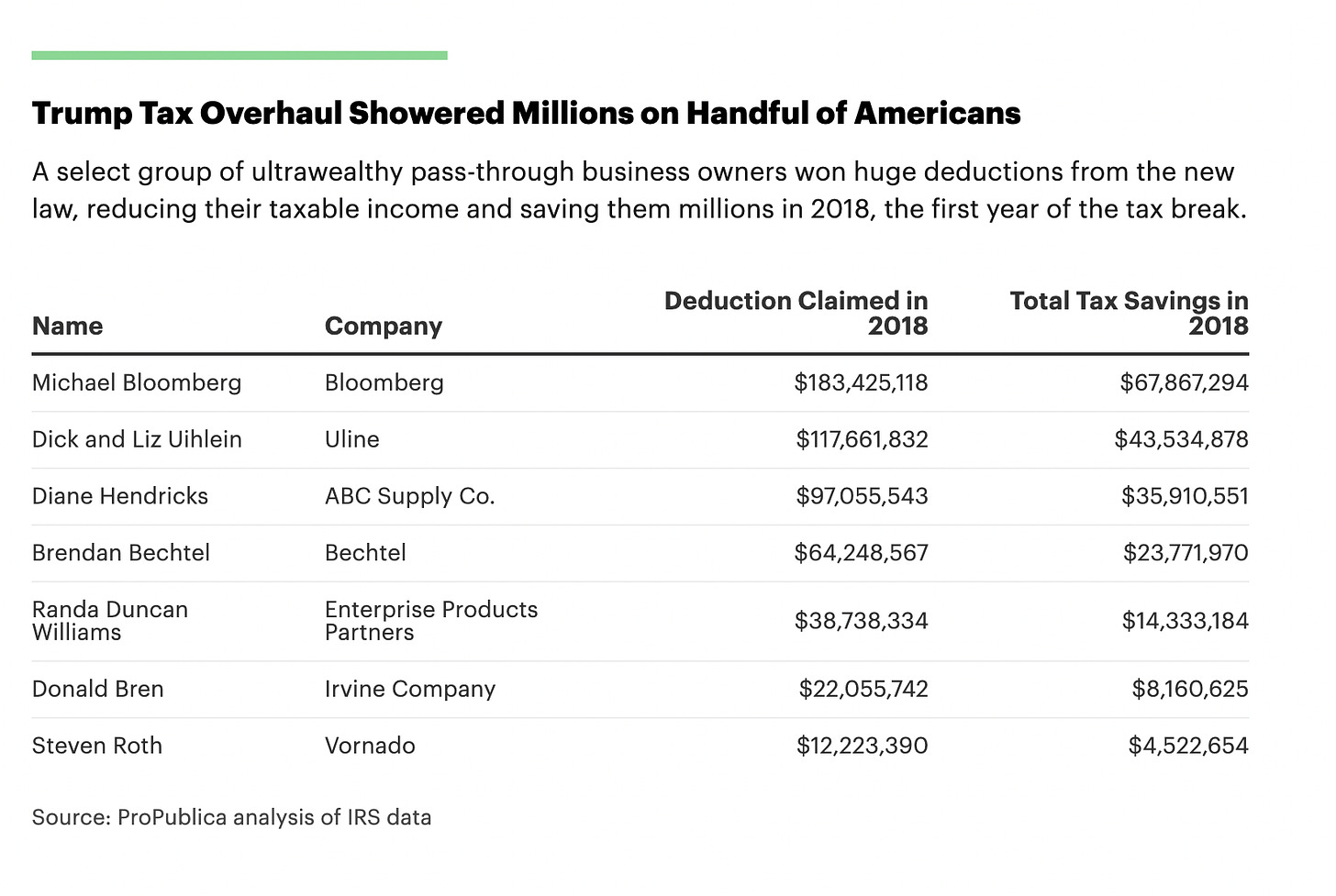

Hendricks and the Uihelins did not lose faith in Johnson, spending $20 million on his seemingly doomed campaign. Their faith was amply rewarded. They benefited disproportionately from the very particular tax cut that Johnson had held out for.

In 2018 alone, the tax break Johnson engineered was worth an astonishing $215 million to his three billionaire supporters, almost one-quarter of the $1 billion benefit the tax cut provided to 82 mega-rich households. Over the course of its 8-year life, the tax cut could deliver half a billion for them.

The story of the Citizens United democracy

This is the version of democracy bequeathed to us by Citizens United, where billionaires can decide to put their thumbs on the scale. I don’t want to claim that Barnes did not have enough money when tens of millions were being spent on advertising on his behalf. Or that money always wins. Phil Knight of Nike, the richest man in Oregon, spent millions to oppose the Democratic candidate for Governor. Ronald Lauder, the billionaire cosmetics heir, spent at least $11 million to boost the Republican candidate in New York. Both efforts failed.

But only a fool would believe that Knight or Lauder have the same political voice as you or I. Their money gives them more influence. Politicians have to be wary of such power, and do what they can to avoid infuriating those that hold it.

With the Johnson case, there is simply a much clearer case that donors that he had gone out of his way to enrich dragged him over the finish line. Johnson and the Uihleins are both given to conspiracy theories. The Uihleins actively fund election denial. But the most straightforward conspiracy in American democracy is the legal one, happening in plain sight, where a Senator can seemingly only be roused from his indifference to his job to help his political patrons.

And yet this political scandal, where the basic facts are well-documented, has never been a feature of coverage in the race. The Hendrick’s and Uihlein’s support for Johnson has been reported on to be sure, but the implication that it is somehow connected to the enormous benefits that Johnson has delivered to them is not.

Every election is, in microcosm, the story of the democracy in which it takes place. The midterms provided many encouraging stories, but this is not one of them. People will draw their own conclusions from this race, some contradictory, some complementary. Readymade narratives about the candidates or the state — Barnes was too progressive, or that he was the victim of racist ads; Johnson keeps winning because of talk radio — come in large part from the scripts provided by the media. In this race, the story that the victory was purchased for Johnson in return for his ability to procure past and future benefits to a handful of billionaires was not told, certainly not in a way that allowed people to understand the context of the blizzard of ads they were watching.

And I wonder why. Have we lost the capacity to be outraged about what John McCain once referred to as “a system of legalized bribery”?