The administrative state of the Empire

A public administration professor on how Andor explores bureaucracy

*Many spoilers ahead*

Throughout the Star Wars movie universe, the basic administrative details of how a galactic empire is run is hinted at but never engaged with. Given the obsessive attention to Star Wars, this has been one of the weak spots of the franchise. For example, characters in the movie Clerks considered Star Wars from the perspective of the anonymous contractors working on the second Death Star.

All right, look-you're a roofer, and some juicy government contract comes your way; you got the wife and kids and the two-story in suburbia-this is a government contract, which means all sorts of benefits. All of a sudden these left-wing militants blast you with lasers and wipe out everyone within a three-mile radius. You didn't ask for that. You have no personal politics. You're just trying to scrape out a living.

See this thread about administrative issues from other Star Wars material, where bureaucratic failures are a theme of the Empire.

The Disney series Andor is the first show to take the details of administration seriously. It may seem like unpromising material. It is a spin-off of a spin-off (Rogue One). There are no dominant characters from the original movies (unless you count Mon Mothma) and no light sabers to be seen. The show is freer as a result. The nominal star, Cassian Andor, does not drive the show in the way that the leads in the other Star War shows do. The show is not about him, but the world he lives in. This gives room for even the most minor characters to play a role. They are treated as real people with motivations, not just blaster fodder.

Andor is to the Star Wars franchise movies what a LeCarré novel is to James Bond movies. It dwells in the gritty detail, petty bureaucracy and moral ambiguity of a shadowy world. In doing so, Andor offers a bottom-up view of how the Empire was run, and how the disparate parts of the rebellion were put together.

Here are some lessons from the show.

Lesson 1: Contracting out is risky

The conflict that drives Andor originates comes from poor contracting out. Two ill-disciplined members of the private security firm (Corpos) are killed by Cassian Andor. Despite the best efforts by their firm’s supervisor to keep it quiet, an enterprising underling, Syril, seeks to hunt Andor down, leading to a bloodbath, and imperial officers directly taking over from the failed contractors.

In a classic work, my Georgetown colleague Kent Weaver explained how bureaucratic politics is driven by blame avoidance. This makes it logical for politicians to contract out services: not only might they be cheaper (perhaps because of the sort of quality shortcuts we see from the private outfit), but it might be able to shift blame away when things go wrong. This is an illusion, however. Another Georgetown colleague, Sebastian Jilke (with Oliver James, Carolyn Peterson and Steven van de Walle), offers experimental evidence that when things go wrong, the public still blames politicians even if services are contracted out. If they want to shift blame, it turns out that politicians are better off keeping services in house, and blaming the bureaucrats.

Lesson 2: The Empire is intensely bureaucratic, with all the accompanying blind spots

Years before the Senate is suspended by Emperor Palpatine, it is clear that the bureaucrats are already in charge, making extraordinary decisions about the running of planets while Senators like Mon Mothma are ignored.

To organize the galaxy, the empire relies upon a giant Weberian bureaucracy. Principles of specialization and formalization are clearly in place. The downsides of bureaucracy are also present. Behind the air of omnipotence, there is plenty of incompetence. The Empire conveys total control, but it is beset with problems.

The biggest problem is that the Empire seems unable to manage people or systems far from its sphere of influence. They are indifferent or actively hostile to local traditions and norms (witness how they organize to destroy those of the Dhani people in episode 6). Their inability to read local situations leads them to overreact to challenges, an overreaction that Luthen and philosophers of the nascent rebellion, like Karis Nemik, are predicting.

Nemik’s Manifesto

There will be times when the struggle seems impossible. I know this already. Alone, unsure, dwarfed by the scale of the enemy.

Remember this, freedom is a pure idea. It occurs spontaneously and without instruction. Random acts of insurrection are occurring constantly throughout the galaxy. There are whole armies, battalions that have no idea that they’ve already enlisted in the cause.

Remember that the frontier of the rebellion is everywhere. And even the smallest act of insurrection pushes our lines forward.

And remember this: the Imperial need for control is so desperate because it is so unnatural. Tyranny requires constant effort. It breaks, it leaks. Authority is brittle. Oppression is the mask of fear.

Remember that. And know this, the day will come when all these skirmishes and battles, these moments of defiance will have flooded the banks of the Empires’s authority and then there will be one too many. One single thing will break the siege.

Remember this: Try.

Such is a classic danger for the administrative state (see, for example, James Scott’s Seeing Like a State). As the rebellion shows power, the political class of the Empire call for more security, oblivious to the costs it imposes on citizens in distant planets, who are swept up in an arbitrary justice system, creating the basis for more discontent.

Lesson 3: The banality of evil

The Empire’s intelligence services may be clearly more professional than the contractors they replace, but they are riven by petty squabbles, turf battles and back-biting.

When we meet Dedra Meero, a supervisor at the intelligence services, it is hard not to root for her. She is surrounded by condescending men, even as she can see the outlines of the rebellion that they cannot. Given the opportunity to pursue the rebellion, she proves a merciless fascist.

Meero and her co-workers seem less inspired by the mission of the Empire than reaching the next rung on the ladder, and are willing to engage in increasingly extreme acts to do so. (This reaches its apex in Rogue One, when the designer of the Death Star is revealed to be a promotion-hungry senior manager).

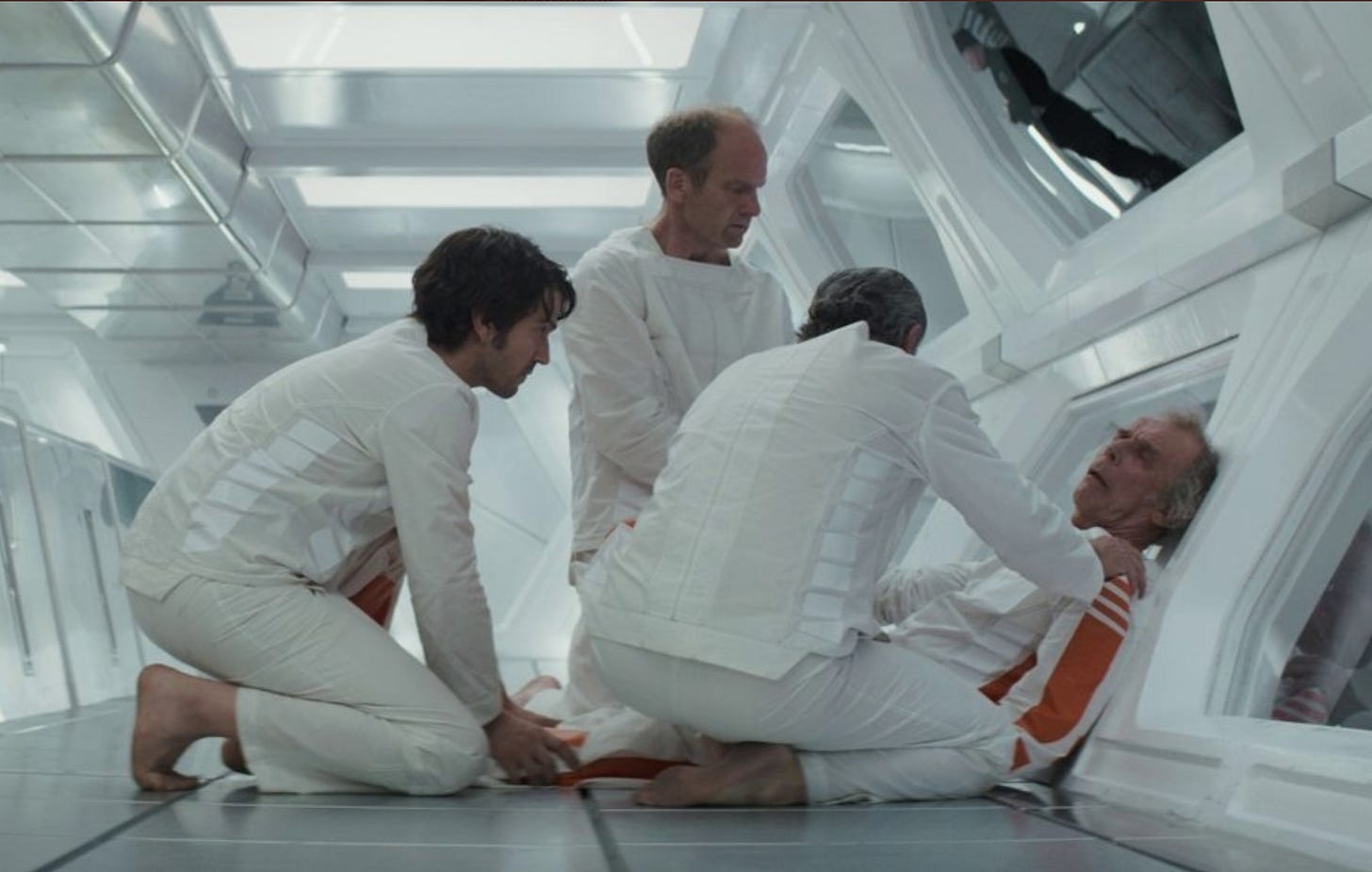

This reflects Arendt’s banality of evil, where bland careersist bureaucrats organize totalitarian regimes. It is not easy to forget the torturer in episode nine who is positively beaming as he explains the new innovations in his craft to the person about to be on the receiving end.

Lesson 4: The Empire is undermined by sabotage

The public response to inflexible overreaction is one cause for concern for the Empire. Another is internal disloyalty.

The issue of what an official is to do when they are facing what they regard as a corrupt administration is one that has become newly relevant in the aged of populism. Albert O. Hirschman outlined three potential options to follow: exit (quitting), voice (raising concerns), and loyalty (staying with the organization). As the concepts were applied to public administration, a fourth alternative was added: sometimes described as neglect, sabotage, or guerrilla government, it means using bureaucratic power to actively undermine the regime.

In Andor, an insider employee, Imperial Lt. Gorn, facilitates the Aldhani raid that forms the central narrative of episodes 3-6. He had fallen in love with a local woman, and watched her killed by the Empire and local customs destroyed. This theme is also there in Rogue One, when we learn that the crippling weakness in the Death Star was deliberately put in place by Galen Erso, who was forced to work on the project after his wife was killed.

Lesson 5: The rebellion as dark network

The rebellion is, in the Star Wars movies, basically Luke, Leia and Han and supporting cast. The rebellion in Andor is different, closer to what organizational theorists Brint Milward and Jörg Raab call “dark networks” that seek to violate and evade the law. It is also an emerging network, where we see the disparate parts before they are knitted together.

There is no single rebellion. We hear about the Separatists, Neo-Republican, the Ghorman front, the Partisan alliance, Sectorists, the Human cultists and Galaxy partitionists! These various groups are short of many qualities, but most critically, they are missing the one thing networks need to function: trust. Saw Guerra points out the different goals of each faction as a reason he would refuse to join them. They have little in common apart from their opposition to the Empire. Individual members of the rebellion see killing each other as an optimal solution to maintaining secrecy.

Lesson 6: The extraordinary toll

To a greater extent than any prior work, Andor dwells on the personal cost that comes with work that involves conflict, risk and deception. This holds just as much for members of the rebellion as it does for the agents of the Empire tracking them down.

There are no medal ceremonies. Failure is the most likely outcome. Some are very aware of the lack of morality of their work. After condemning dozens to die to protect a well-placed spy, Luthen (episode 10) reflects on the costs.

What is my sacrifice? I’m condemned to use the tools of my enemy to defeat them. I burn my decency for someone else’s future. I burn my life to make a sunrise that I know I’ll never see.

Luthen and the rebellion are operating in the shadows of an authoritarian regime, and to do so requires ruthlessness. Since the fate of Cassian Andor is known to anyone who has watched Rogue One, one of themes of the show is how he becomes the person willing to die for the rebellion. Andor shows Cassian evolving from someone with a hatred of the Empire to someone capable of doing something about it, even if it involves sacrificing himself and others.

This is very different than the standard “light vs. darkness” Star Wars fare. No one is expecting “the force” to save them. Indeed, the first mention of “darkness” comes at the end of the season, in the context of Maarva’s speech (at her own funeral, which is a neat trick). Her call to community revolt — to wake up and do something about their servitude — can be seen as the complement to Luthen’s self-loathing assessment of the costs of building the rebellion:

We were sleeping. I’ve been sleeping. I’ve been turning away from a truth I wanted not to face. There is a darkness reaching like rust into everything around us. We let it grow and now it’s here. The Empire is a disease that thrives in darkness. It is never more alive than when we sleep. It’s easy for the dead to tell you to fight. And maybe it’s true, maybe fighting is useless. But I’ll tell you this. If I could do it again, I’d wake up early, I’d be fighting these bastards from the start. Fight the Empire!

The psychological toll exerted on the main characters in the rebellion reflects the general tension of fighting totalitarianism; this toll is also imposed on minor characters living and dying under the Empire. At some point they can decide to no longer accept the incremental loss of freedom.

As Adam Serwer discussed, this is not the Star Wars of secret princesses, or mysterious fathers. Most characters have mundane concerns. They are lonely, venal, jealous and petty, with bad marriages, overbearing parents, rebellious children, and ill health. They are also idealists, or people who are simply sick of living under the thumb of a distant authoritarian. In doing so, Andor puts the human politics back into Star Wars.

Dan, what a wonderful piece. As someone obsessed with both politics and, as a kid, Star Wars, this show has been an epiphany from the schlock of the recent past

What a brilliant and apposite line: “Tyranny requires constant efforts. It breaks, it leaks. Authority is brittle.” Authoritarians everywhere need to remember that...