Rationing Rights

How the Harris Plans to Expand Medicare Could Deliver Long-Promised Help for the Aged and Disabled

Kamala Harris’s recent proposal to expand Medicare home care supports for disabled people and older adults was personal for me, and not just because I’ve researched the topic. My oldest daughter has a rare developmental disability, which means she will need these supports.

A few years back, having recently moved to Maryland, and with my daughter rapidly approaching age 18, I needed to figure out her options. I spent weeks searching online and making fruitless phone calls trying to understand the options for community-based supports in Maryland, which like in every state, are primarily funded by Medicaid.

I got nowhere. Phone calls went unreturned. I ended up on state websites that provided no intelligible information on what program would make sense for her, who to talk to, or how to apply. I did, however, find out that there were waitlists for these services. Long waitlists. Nearly 30,000 people were on them. And those were the people who figured out how to apply, or bothered to apply after realizing the low odds of getting services.

So I paid $500 an hour for a consultant to help me understand my daughter’s options. This is a privilege that most people simply don’t have. After explaining all of the programs, processes, and strategies for applying, I asked her when my daughter would likely be able to receive services. She first explained that it was nearly impossible to figure out where you were on a waitlist, the precise explanation for why you were stuck on it, or how long you’d be on it. But she said that the odds were that my daughter would only get off it when I myself was either disabled or dead.

Maryland is not unique and our family is not alone. As one expert described it, both disabled people and older adults, and the families that care for them, are stuck in an administrative “no man’s land.” The vast majority of states have a convoluted and unnavigable set of Medicaid programs covering these services, most of which have lengthy waitlists. The only certain option is a nursing home, which unlike home care, Medicaid is required to fund for those eligible.

How did we end up here? And why are states, which administer these programs, exacerbating an already frustrating reality—qualifying for the benefit does not mean you’ll receive help—with an onerous and opaque bureaucratic process? States are doing so, in part, to hide not just the deeply unpopular practice of rationing, but also possible violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

It wasn’t supposed to be this way

Medicaid has actually significantly increased spending on home and community-based care. In the early 1980s, it largely only funded institutional care for the aged and disabled. Today, however, over 60 percent of Medicaid funding for long term care is for home and community based services. Medicare does not cover long term care.

A mix of cultural, legal, and policy changes fostered the guiding goal that disabled people – and to be clear this includes older adults who develop disabilities later in life – had a right to live in the community, and not be segregated within institutions. The hard work of disability rights advocates, and the passage of the Americans with Disability Act, led to a series of Medicaid policies that increased spending on home and community-based services.

A pivotal moment in this history was the Olmstead Supreme Court decision in 1999. Two women from Georgia, Lois Curtis and Elaine Wilson, both of whom had mental illness and developmental disabilities, were repeatedly placed in psychiatric institutions despite their beliefs, and the views of their physicians, that they would be better off in community-based programs. Georgia, while not disputing these facts, argued that financial constraints prevented the state from providing those supports in the community.

The Supreme Court ruling on the case helps explain the current day convoluted policy environment. On the one hand, the Court established that living in the community was a basic right because institutionalization limited “the everyday life activities of individuals, including family relations, social contacts, work options, economic independence, educational advancement, and cultural enrichment.” On the other hand, the state’s obligation was not “boundless.” States could employ budgetary controls, like waitlists, though they must “move at a reasonable pace.”

States are rationing by making eligibility processes impossible to navigate

The Olmstead ruling, in practice, has meant that the right to live in the community is a conditional right. Unlike every other Medicaid program, be it health insurance or institutional care, home and community-based services are not entitlements. Eligibility does not guarantee access to benefits.

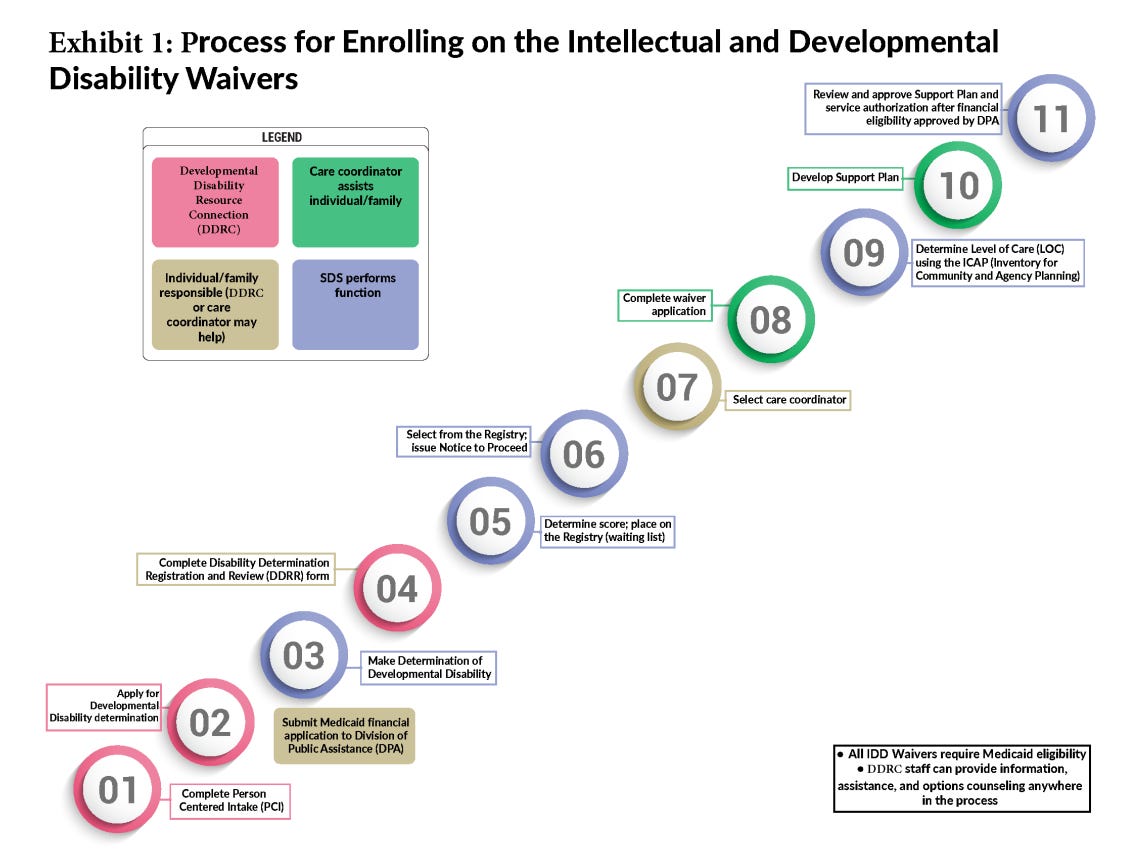

So how do states ration in practice? The first rationing mechanism is by building a confusing and onerous eligibility process. Look at the figure below, which is Alaska’s representation of their eligibility process. Indeed, the state notes that “because the current process could be considered overly complex, families may choose not to apply if it looks like they are unlikely to be selected for a waiver slot in the near future.”

States are rationing with waitlists

The second cost control is direct. Thirty-seven states currently have waitlists. The average time people spend on waitlists ranges from 3 years for those with physical disabilities to 5 years for those with intellectual disabilities.

But wait times vary wildly across states. For example, in Kentucky, it would take 168 years to pull all 8000 people off of their waitlists. In Florida, the waitlist is seven years long. This is a hard pill to swallow for the people needing these services.

JJ Holmes is an 18 years old Floridian currently studying for the SAT and applying to colleges. He also has cerebral palsy. His 60 year old mother needs to lift him out of bed, help him get dressed, and otherwise provide significant amounts of support. He’s been on a waitlist for the past 16 years.

His mother is terrified of what the future holds, and what will happen when she can no longer physically provide care, with institutionalization being the most likely outcome.

So is JJ, who said: “I’m scared.I want to live independently at home instead of being in an institution. I couldn’t imagine what my life would be like. I would have no life to be frank”

The confusing and opaque nature of waitlists serves to conceal rationing

Current estimates are that well over a half of million people are on these waitlists. But this is likely a substantial underestimate of those actually needing home and community based services. As the State Department of Health in Alaska noted, the onerous application process and low likelihood of actually receiving benefits discourages people from applying.

But states are also deliberately trying to conceal the numbers of people waiting. In 2018, Louisiana claimed it had eliminated its waitlist. PBS News reported:

In 2018, Louisiana’s waitlist for IDD services had nearly 30,000 people. To emphasize community-based care, the state introduced a new system called Screening for Urgency of Need (SUN), which identified individuals in urgent or emergent need of services and provided them with the necessary assistance. Those who didn’t meet the criteria were placed on a registry and were screened regularly or upon request. By 2020, the waitlist had been completely eradicated.

But the waitlist wasn’t eliminated. They had simply transferred thousands of individuals from the waitlist to a “registry.” In the spring of 2023, 13,000 people were on this registry.

States are sometimes explicit about the financial reasons for the waitlist. The Louisiana’s Department of Health website describes the new policy as follows:

Prior to this change, it would have cost the state $832 million in new state and federal dollars to address the needs of all of the individuals on the waiting list. However, with this approach, meeting the needs of individuals with disabilities is resolved with a $43 million investment (passed by the Legislature in 2018) which includes state funds and a federal match.

Many states, similar to Louisiana, use “priority scores” to determine who comes off waitlists or who is even allowed on them in the first place. This criterion, which is effectively the primary determinant of who does or does not receive services, is also opaque.

How opaque? Ohio, which pulls those labeled as having ‘substantial risk’ off of their wait list, notes:

There’s no definition of substantial risk. This was intentional because no definition will be able to include every situation and/or nuance that can occur, nor can a definition speak to “degrees” of risk or “harm”. Consider the actual definitions of the words themselves: Substantial = having substance, real, true (not imaginary or illusory); Risk = possibility of loss or injury; peril (danger); Harm = physical or mental damage; injury. Assess to what degree of risk there’s to the person and what is the actual likely harm that could occur in order to help you assess the person’s situation. Is it substantial (real, true, and is there substance to it)?

This is perhaps why disabled individuals and their families feel so frustrated. One woman, whose brother was stuck on a waitlist in Kentucky, said:

What I still find perplexing is that (FSSA) could not tell me where Jim is on the waitlist and how many people are in front of them? (They) said they don’t know, they have not been told…I said, ‘Well, surely someone must know. It’s computerized … that doesn’t seem logical to me.’ It is very difficult to navigate. This is information that is vital for people to have.

Making rights real

Though Olmstead established living in the community as a right, the choice to use non-entitlement Medicaid programs to implement it led to a dystopian set of administrative burdens that tightly ration that right.

While the Biden/Harris Administration issued new guidance to at least push for some transparency in these processes, the real solution is more straightforward. Make home and community based services an entitlement, a basic right. Harris has proposed to do this through Medicare. It could also be done within Medicaid.

It’s not a radical proposal. Both Democrats and Republicans in state legislatures have pushed to end waitlists and expand access. This cannot be a private solution. Almost no one can afford to pay privately for these services, and even if you could, you can’t replicate the web of organizations and supports that truly make it possible for people to be fully integrated into society.

Nearly forty-five years after the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, it’s time to make sure we meet its goal: “to make it possible for people with disabilities to participate in the everyday commercial, economic, and social activities of American life.” The Harris proposal is a tangible step to making this right real.

Pamela Herd is the Carol Kakalec Kohn Professor of Social Policy at the Ford School of Public Policy, University of Michigan. Her research focuses on inequality and how it intersects with health, aging, and policy.