Permitting Reform in Pennsylvania

Some good news on the nuts and bolts of making government work better

If you are interested in ways to improve government, the last few weeks have been about was bleak a period as I can remember. I’ve been writing extensively about the damage being done at the federal level, but am still looking for positive examples to celebrate. Some of those examples come from research we are doing at the Better Government Lab. We just unveiled a shiny new website that details our efforts to improve how public services are delivered, so check it out! Some examples also come from government reforms worth sharing.

I published a new report at the Institute for Responsive Government on Pennsylvania’s recent success in reducing burdens for business, nonprofit or individuals to receive a permit, license or certificate they had applied for. It’s the sort of non-partisan good government project that should be a no-brainer for any state trying to better serve its citizens.

This effort was spearheaded by Governor Josh Shapiro. Shapiro won national attention when he was able to re-open within 12 days a critical stretch of I-95 that had collapsed. For example, Jen Pahlka wrote “the public wants I-95-ness.” In the Washington Post, E.J. Dionne wrote: “Shapiro’s I-95 feat has made him a leading voice for the transition to a less fractious politics. Building an actual road fast is an apt symbol of the journey the country needs to take.”

Shapiro was already applying “I-95-ness” to everyday government services. People’s time is valuable, and governments should not waste it. Yet administrative burdens restrict access to a wide variety of public services, causing frustration and disappointment. Pennsylvania had garnered a reputation for red tape when it came to administrative processes. Such delays were cited as a reason why businesses were not building new factories in Pennsylvania, or why hospitals could not meet staffing shortages. Businesses felt like there was no direct government contact to guide them through the bureaucracy.

In 2021, more than half of the nurses seeking licenses to work in Pennsylvania faced at least a three-month wait. At a time of chronic nursing shortages, during the height of the pandemic, some nurses simply found jobs in other states. There are valuable public health benefits to verifying that nurses are qualified – it should not, however, take three months. The time lost does not make the nurse more qualified, or the patient safer.

Communities can reasonably argue about what is the appropriate level of regulation, but this is just one aspect of permitting. Another equally important aspect is whether a regulatory framework, once in place, occurs predictably, expeditiously and transparently. In simple terms, this means that those seeking a permit have good customer experience.

Pennsylvania reformed the state’s permitting application process to provide Pennsylvanians with transparency, accountability, and a better overall customer experience. The governor’s team took the following specific steps:

Over the past year, the state has boasted of the success of PAyback and related reforms. Notable results include:

Reduced time to receive an initial corporate license from eight weeks to two days.

Reduced small business verification times at the Department of General Services from 15 days to 10 days.

Reduced new teacher processing times at the Department of Education to 2-3 weeks.

Eliminated a backlog of 35,000 Medicaid provider applications and renewals in six months.

Eliminated a backlog of birth certificate amendment requests from 6,200 to zero.

Reduced the backlog of applications at the Department of Environmental Protection by more than 90%.

In the year since it was created, PAyback has issued just three refunds.

The key components of Pennsylvania’s success appear simple: the governor ordered agencies to set reasonable targets and meet them, or lose money. However, major structural reforms are never as simple as they appear. Based on interviews with officials who led and participated in the efforts, I tried to understand how the Pennsylvania team turned permitting reform into a reality. Their success can be traced to four main components:

A clear mandate for change:

Actionable plans to allocate personnel, resources, and direction:

Specific and realistic targets:

Permission to dive deep into existing processes

A Clear Mandate for Change

Shapiro announced his commitment to permitting reform in his first week in office. Executive Order 2023-07 Building Efficiency in the Commonwealth’s Permitting, Licensing, and Certification Processes was signed on January 31st, 2023. The Order gave agencies 90 days to document their permitting process — the types of permits they provided, the relevant statutory guidance, the fee charged, and a recommendation for a target time by which permits should be processed. The order also specified that applications whose length exceeded the recommended target be issued a refund.

A key component to Pennsylvania’s success was Governor Shapiro’s willingness to use some of his political capital on permitting reform. Making the public bureaucracy more responsive involves fixing back-end administrative processes, rather than unveiling a compelling new policy. It also requires leaders to be willing to ask hard questions of agency leaders, which can sometimes ruffle feathers. But Shapiro saw solving such problems as essential to a broader economic development strategy and enabling greater labor force participation.

This specificity, and the support of the governor’s office, created a tangible framework to move forward. While the 90-day target for documenting all permits and their processing times was challenging, it was still achievable. The time-sensitive mandate propelled a reform that some aides suggested would have otherwise taken a year or longer. Cabinet secretaries understood they would have to either meet the deadline, or explain directly to the governor — in an in-person meeting in front of their peers — why they couldn’t. The visibility of the initiative also encouraged a sense of competition among cabinet officials. The mantra of “moving at the speed of business” was widely adopted among those working with the governor.

Gubernatorial leadership also mattered in resolving coordination problems across agencies. A good example of a coordination challenge is in data sharing. Agencies might be unwilling to share data, and establishing data sharing agreements may take considerable time. One member of the governor’s team noted defensiveness about who owns the data, while another emphasized that it took time to communicate that “this is state data; this is not agency data.” Another noted that the work is challenging because it requires the co-operation of front line staff to collect and analyze the data, who might see little value in the work. But as agency leadership demonstrated their commitment to the reform, it mitigated resistance at lower levels. A crucial point given the potential for abuses of data sharing we are seeing at the federal level, is that such sharing was a) legal, and b) focused on improving services.

Leadership prioritization of reforms is easier said than done. This is especially true for administrative reforms, where all too often a president, governor or mayor will declare a government reform commission, but then show little interest in the fruits of its labors. Governors can simply declare something to be a goal, but if they do not continually devote time to it, and emphasize its importance, it will be less likely to be viewed as a significant priority. Research on transformational leadership in the public sector emphasizes the centrality of leadership commitment of time, including time spent communicating their goals. Effective leaders not only set targets, but communicate directly with those responsible for delivering, and to the broader public about the public interest value of the reform. Shapiro did this, and any leader seeking to emulate his success would have to commit to doing the same.

Specific Plans to Allocate Personnel, Resources, and Direction

While the leadership of Shapiro was essential to improving permitting reform, it alone was not sufficient. The governor also established new state capacities, and empowered leaders in charge of these offices. Governor Shapiro created two new units within the governor’s office: the Office of Transformation & Opportunity (OTO), and the Commonwealth Office of Digital Experience (CODE PA), and brought in outsiders to lead the new offices. OTO was led by tech entrepreneur Ben Kirshner. Bryanna (“Bry”) Pardoe had previously worked in digital service in the healthcare industry before she led CODE PA. These two units would come to play complementary roles in facilitating the reform.

OTO serves different functions, centered around economic development. These include identifying and reducing administrative bottlenecks that affect businesses interaction with the state, coordinating economic development and innovation strategy, developing a performance management system for the governor’s office, and providing a single point of contact for businesses on complex projects that require coordination across agencies.

Within government, OTO served as the governor’s emissary to agencies, the spear carriers for the permitting reform. They did the daily work of pushing agencies forward, and providing help for them to succeed. According to Ben Kirshner:

You need someone to actually push the buttons and push the people and set up the meetings and make sure there’s progress being managed. And that’s where our role comes in. It’s kind of like the catch all for getting stuff done.

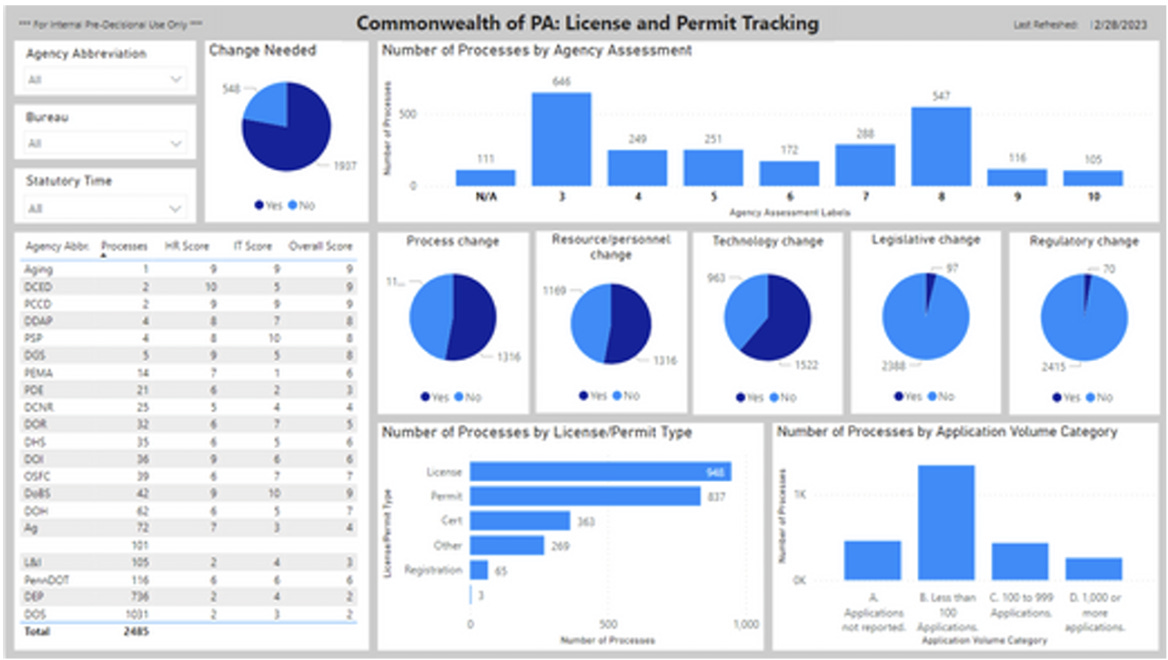

The first task for OTO was to make the challenge legible. The state was obviously involved in issuing licenses, permits and certificates. But how many? What was the process for each of them? How long did each take, on average? The state did not have the answers to those questions in a single place. And compiling this information was a bigger challenge than they anticipated: “brutal” and a “huge undertaking” according to those involved. Agencies did not have this information at hand, and where reporting was, at best, annual, meaning the data was not timely. Some agencies might require more flexibility with a tight deadline based on the number of permits it processed. The Department of State had 1,069 permits while the Department of Agriculture had one. Another factor is how digitalized the process is: the higher the proportion of digital permits the easier it is to pull reports relative to paper-based permits. Some agencies also have more experience in collecting and reviewing data, which makes it easier for them to account for their permitting processes.

CODE PA was created in April 2023, under another executive order from Shapiro. The office is an example of the growing role of civic tech in government. In-house civic tech expertise resolves shortcomings of relying primarily on contracted out technological services. Procurement processes can be slow and unwieldy when government wants to do something quickly. For the PAyback tool, the government did not have to set up a procurement process to hire an outside vendor, something which could have taken months. According to Bry Pardo, head of CODE PA:

It would have been incredibly difficult for us to be able to manage that if it was a traditional IT shop balancing several other projects that weren’t able to take that dedicated focus, and really deploy a dedicated squad.

Another advantage of in-house expertise is that CODE PA was attuned to the goals and evolving demands of the governor’s reform, rather than treating it as a static contracting task. Such flexibility is often at odds with how governments design their procurement process, which encourages specifying what the final product looks like ahead of time, a practice that fails to reflect the reality that building good digital products is an iterative, agile process. CODE PA estimated it would also have cost more to hire an outside vendor, and taken longer to build the new digital interface. In-house civic tech capacity was therefore both quicker and cheaper in this case.

One aspect of civic tech is an emphasis on human centered design, which at its heart is a series of tools to take the user’s perspective on processes. For example, CODE PA pushed agencies to simplify the volume of data and number of fields being sought from applicants. When they built out the prototype of PAyback, CODE PA conducted focus groups with constituents on what they would like such a tool to deliver and employed user testing with each iteration.

Specific and Realistic Targets

Creating Reference Points

Public organizations lack the equivalent of a natural bottom line of profitability. And so, they must rely more heavily on performance measurement systems. For such systems to be informative, they must be comparative. The answer to the question of “how well is this public organization performing?” will always be another question: “Compared to what?” The comparison requires some sort of reference point. Reference points tend to be either historical (how are we doing compared to the past), social (how are we doing compared to peers), or target-based (how are we doing compared to our goals).

For permitting reform, Pennsylvania went from no widely used reference points to track performance to developing historical comparisons and attaching visible targets to maintain and improve historical performance. For performance systems to take hold, creating performance data is not enough. Data needs to be used, which implies creating organizational routines of use, sometimes called learning forums or data driven reviews.

The emphasis on measurable data encouraged the creation of agency-level dashboards. Ramez Ziadeh of the Department of Environmental Protection noted how the permitting reform had caused discussions of data on a weekly basis: “We show everybody what the numbers look like, how many applications are pending, how many in each different program area, in different regions.” The data allows supervisors to identify which reviews in their sections or regions are coming close to deadlines and prioritize those reviews.

Making Progress Visible

One challenge for public sector performance systems, even well-run ones, is that the public often fails to pay attention to the progress made. So, the designers of such systems must work to communicate successes. Shapiro’s speedy rebuilding of I-95 after its collapse represented a large and visible demonstration of government capacity in action, achieving an outcome that tangibly affected people’s lives in a way that beat public expectations. Permitting reform is less visible, but is consequential to people’s direct experiences of government, and is more tangible than many other types of reforms.

Pennsylvania’s focus on benchmarks for a single but important policy domain made it easier to communicate progress that the public could understand. The refund promise also helped to communicate the impacts of the reform, sending “a signal to the public as well like trying to regain some of that trust we might have lost” said Orlando Olamonte, deputy secretary of policy and planning at the governor’s office of administration, while noting that PAyback is one the first thing that members of the private sector bring up in economic development discussion. “They’re like ‘Oh, we loved that money back guarantee.’ And it sounds so obvious now in hindsight.” The administration facilitated this communication with press conferences and press releases, engaging the governor and cabinet secretaries in public appearances when a significant milestone had been achieved.

Permission to Dive Deep Into Existing Processes

The new permitting performance system made it easier to identify problems, and the refund promise, along with the governor’s support, gave agencies strong incentives to make progress. But agencies still needed to engage in a process of solving the particular problems they faced to meet their goals. Much of OTO’s role was in working with agencies to fix broken processes behind the scenes, especially when the problem or solution involved multiple agencies.

An example of this type of problem solving came with business licenses. About 1,000 new requests were coming in each day, and the state had the capacity to review about 1,200 applications daily. The problem is that it also had a backlog of 21,000 applications, meaning that applicants faced delays of up to 8 weeks. The officials who oversaw the process identified the problem as simply finding enough staff, even on a temporary basis, to resolve the backlog. The solution was to temporarily reallocate civil servants from other agencies to help resolve the backlog. This raised coordination issues between agencies, and questions about whether it was possible to make such reallocations without violating civil service rules. OTO coordinated multiple agencies, budget and Human Resources staff and general counsels to facilitate the transfer. With an agreement in place, enough staff were on hand to eliminate the backlog over a weekend, turning an 8-week process for new applicants into a two-day wait.

Problem-solving worked in cases where agencies believed that they would not be punished for poor performance, but were willing to work collaboratively. OTO tried to facilitate these cultural traits. According to Ben Kirshner:

We came and we said, we are here to help…we didn’t come in and say we are the smartest guys in the room. We said we’re here to help you…What do you need to be better at your job? We are the resource people, but we don’t know what to give you unless you tell us what you need.

The governor’s office had to manage change while pushing agency officials beyond their comfort zone, asking them to collect and analyze data in new ways, and establish new performance metrics. One official noted that the change can be nerve-wracking, and much of their job involved:

assuaging peoples’ fears about the outcome of this work, patiently answering questions about what we were doing and why, and generally coaching them through the various stages of the initiative. We really needed people to see us as a partner, not just the driver, of the project.

To help identify the source of problems, OTO asked agencies to self-grade specific permit processes, and then focused on the ones with the largest problems. It also tried to identify the cause of the problem.

OTO found that most permitting problems fell into one of a handful of buckets: technology, legislative, regulatory or business process issues, and asked agencies what kinds of support in those areas would help the most. Based on agency input, OTO developed a report card for each agency they labeled “Permit Reform Summaries”, and offered options to solve the biggest problems agencies faced. In many cases, the source of the solutions also came from agency staff. “A lot of these agencies looked at the data and saw, ‘Oh my God, we can fix this.’ And they started fixing it” said Kirshner.

In some cases, this meant new staff. For example, where agencies had vacancies, OTO pushed the prioritization for hiring those with permitting responsibilities first. While agencies might reflexively emphasize staffing needs, part of the problem-solving conversations also meant challenging existing status quo approaches in ways that agencies might not normally do, pushing them to re-examine and re-engineer those processes.

Bry Pardo of CODE PA described it as:

The willingness to push and ask, why are we doing it this way? What value is this driving for us?…And so it’s building the relationship and the confidence in the agencies that they can do those things, but also putting that end user right at the middle of everything that we do.

Agency staff report that being pushed to reexamine existing processes helped to identify unnecessary redundancies and steps in the review process, developing more responsive standard operating procedures as a result. Simply creating baseline data allowed conversations about improvements to happen. They also allow target improvements. One official noted that if a target for a specific permit is 30 days, and their average performance is 12 days, this allows a lowering of the target. But without baseline data, such assessments cannot be made.

Another partner in problem-solving was the Office of General Counsel. A barrier to government innovations are beliefs about what the existing law requires and prohibits. In many cases, such beliefs may be incorrect. OTO involved the Office of General Counsel from the governor’s office, and their counterparts in every agency. Many of the underlying laws were written for another era, leaving significant room for how they should be interpreted today. The Office of General Counsel emphasized the goal of the executive order, communicating the need for legal compliance, but also encouraged agency lawyers and other staff to look for innovative solutions, and to communicate questions on what was feasible. This made it difficult for anyone involved to claim that legal constraints prohibited permitting reform.

One final lesson from this piece is that Pennsylvania improved services by talking to people who work in those services, leveraging expertise and insight, and investing in capacity rather than destroying it. They were able to do this and still quickly generate large positive changes. I will put my money on this model of reform over slash-and-burn every day of the week. It requires skill and effort though, as well as some faith that core government tasks have value.

For Pennsylvania, continuing success on permitting reform will require dealing with long-run challenges, especially legislative and technological ones. The 2023/24 state budget allocated millions to modernize permitting processes and especially to help with antiquated technology in some agencies. In other cases, there are legislative questions about what functions need licenses, or whether some regulatory requirements can be relaxed. For example, the state legislature passed a law that removed regulations requiring hair braiders from having 300 hours of training. Another solution is expanding the use of interstate compacts, where a certification in one state is recognized by another.

Even with these long-run challenges, Pennsylvania has shown remarkable progress in a relatively short period of time, without major new investments but enabled by judicious capacity improvements, gubernatorial leadership, and problem-solving, to make the most of the new target and money-back guarantee system. Pennsylvania’s success builds a helpful roadmap for other states to follow as they strive to build a more responsive state government.

Great piece, Don. I realize that civil service and public administration is supposed to be non-political, but given that a major attack line on the right is "government is the problem", you make a case that improving delivery of government services is political just as attacking government services is political.

People who believe that government has a role to play in making people's lives better should start looking for these kinds of opportunities — and need to be creative. Full disclosure: I'm currently stuck on a kitchen/bathroom renovation because the city of Chicago (formerly known as "the city that works") has a huge backlog of inspections. The excuse: we don't have the budget to hire the inspectors.

But a creative solution would be to: (a) establish a minimum response time on inspection requests (to a citizen five working days would seem reasonable); and (b) allow citizens to hire and pay out-of-pocked for approved companies to perform inspections subject to city oversight. Would this be challenging? Sure, but it is a solvable challenge. Might it be subject to abuse? Sure, but then address the potential abuses. Don't just throw up you hands and say "there's nothing we can do without more money".

What destroys citizens confidence in government is the failure of government to help citizens get on with their lives.