New SNAP Work Requirements Are a Bigger Problem Than You Think

The debt-ceiling deal will close a crucial safety valve for older adults in poor health

As details of a debt ceiling deal emerged, many breathed a sigh of relief. Not only will we avoid a dystopian collapse of our financial system, President Biden didn’t cave to some of the Republican’s most mean-spirited welfare cuts. In particular, work requirements in Medicaid, which passed the House in April, disappeared from the final agreement

Contrary to Republican claims, work requirements do not lift people out of poverty, but mostly function to exclude people from benefits they are eligible for by imposing administrative burdens, while doing little to encourage labor force participation.

The White House even won exemptions from work requirements for veterans, teens emerging from foster care, and homeless people, who are especially negatively affected by the paperwork that comes with work requirements.

The most substantive compromises the Biden administration made were to tighten requirements on the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program (TANF), and extending work requirements in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to those aged 54 and younger without dependent children. Currently, the requirement that individuals work at least 80 hours a month to receive SNAP benefits applies only to those aged 49 and younger.

The conventional wisdom is that the effects of additional work requirements will not be all that large. TANF is a relatively small program, with only about one in four people eligible receive funding. The changes for SNAP also seem fairly mild. This assessment from Paul Krugman reflects the sense of relief among progressive policy wonks.

But the effects on SNAP are being underestimated in ways that are only apparent if you look closely at the nuances of how Social Security disability programs and SNAP interact. SNAP is a critical safety valve for people trying to access Social Security Disability programs — for which delays in benefit receipt can extend into years. The expansion in work requirements for this age group seems innocuous, but they are highly consequential. Even those who dislike work requirements don’t fully understand the ramifications.

The gist: Those aged 50-54 face both rapidly accelerating declines in their health and a disability benefit system that is increasingly difficult to access. The one safety net program that protects them during this vulnerable period, SNAP, will now be far less accessible.

We get a lot sicker in our late 40s

The 50-54 age category coincides with a time when peoples’ health gets substantially worse. At the mid-to-late 40s disability rates, and the general onset of poor health, accelerates rapidly. The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System shows that the fraction of those aged 50-54 with a disability rises to 26 percent, from about 17 percent among those ten years younger.

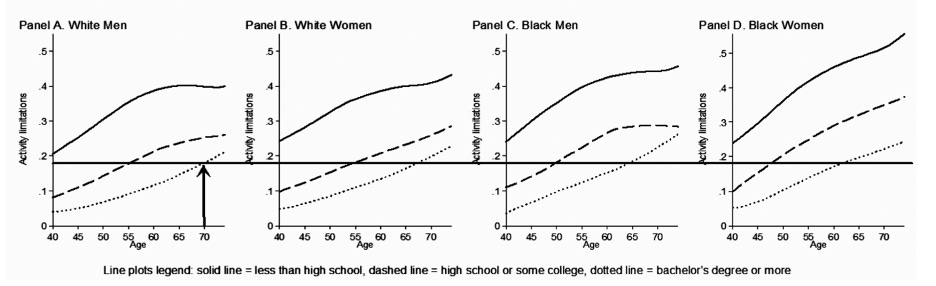

And among those most likely to rely on programs like SNAP, disability rates are especially high. The gaps in health outcomes varies enormously by educational attainment. For those without a high school degree, the disability rate among those aged 45-64 is as much as 6 times higher for than for those with a college degree.

More broadly, white high school dropouts reported more activity limitations at age 40 than the college-educated report at age 70, a gap of more than 30 years. In short, those with lower educational attainment experience the onset of poor health at much younger ages, decades earlier.

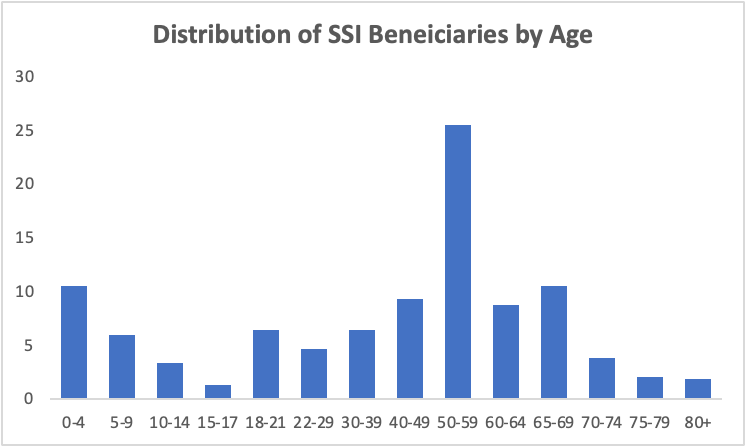

Not surprisingly then, there is a large uptick in participation in Social Security disability programs around age 50. Among those on Social Security Disability Insurance, the fraction of beneficiaries doubles between ages 45-49 and 50-54. This pattern also holds for the Supplemental Security Income program, which is targeted at disabled adults with low incomes. While 9 percent of SSI beneficiaries are aged 40-49, 25 percent of beneficiaries are between the ages of 50-59.

One critical feature of disability policy implementation facilitates this uptick in benefits *at age 50.* The key to disability benefit eligibility is not simply documenting a disability, but documenting that it impedes your ability to be employed. A procedural expectation that shifts with age is that applicants can easily adapt into new types of employment that can accommodate their disability. The 50 year mark is a key turning point in this procedural standard, as disability examiners acknowledge that the options for older workers with disabilities are fewer. Consequently, a lot more people apply, and then receive disability benefits after age 50.

But wait! Aren’t disabled people excluded from the work requirements?

Yes, but this is where administrative burdens matter. In order to prove you are disabled, you must become eligible for Social Security Disability, either Social Security Disability Insurance or Supplemental Security Income. But this process takes significant amounts of effort and time. It is notoriously difficult. Not only does it require reams of paperwork and documentation, it requires effectively navigating a complex medical diagnostic process to verify one’s eligibility. Indeed, about 10,000 people die every year waiting for their application to be processed.

The net result is that it can take years to prove disability in order to access either SSDI or SSI, as well as now prove that you can’t meet the work requirements for SNAP.

And the wait times have been steadily increasing. Between 2014 and 2022, average wait times rose from 106 days to 183 days. The average beneficiary now waits six months to access their benefit, and *prove* their disability.

A key problem is that lots of people who are actually eligible are initially denied benefits. Nearly one-third of those who eventually receive disability benefits are initially denied. And there is evidence that many appeals subsequently denied by administrative law judges done so incorrectly. This trend has substantially worsened over the past 10 to 15 years, with judges frequently ignoring medical specialists. Given this evidence, we should worry that there are many disabled individuals who should be receiving benefits, but are not.

Those aged 50-54, who will now face work requirements to receive SNAP, may face some of the toughest administrative burdens in the disability programs. Among those 40-44, 29 percent of those denied benefits in 2012 received them by 2016. For those aged 50-54, however, 52 percent who were denied benefits in 2012 received them by 2016.

SNAP benefits are a crucial stopgap for people waiting for disability benefits — one that will now be much harder to access

Those aged 50-54 face rapidly accelerating declines in their health and a disability benefit system that is increasingly difficult to access. The one safety net program that protects them during this vulnerable period, SNAP, will shortly become less accessible.

Indeed, there is ample evidence that SNAP helps protect disabled people as they attempt to transition to disability benefits. One study tracked people during the SSDI application process to see how they got by. After looking at programs including Unemployment Insurance, Workmen’s Comp and TANF, they found SNAP was the largest source of economic protection. The longer individuals waited for their application to be processed, the more likely they end up on SNAP. By 8-10 months after the initial disability application, about 25 percent of those who had applied were receiving SNAP benefits. The rates are likely much higher for those applying to SSI because it targets beneficiaries with lower incomes, and thus more likely to qualify for SNAP.

Over the coming years millions of Americans may now face substantial new administrative barriers just at the point where they need relief the most. Those with poorer health struggle more with administrative burdens. As their health declines, and their ability to work along with it, many older Americans will never receive the benefits for which they’re eligible, while others will face significant delays.

While the outcome of the debt negotiations could be much worse, including an unprecedented economic catastrophe if we default, the new SNAP work requirements will cause more damage than we’re currently acknowledging. It could be that negotiators do not understand the implications of these changes, or that some of them understand the impacts all too well. But there needs to be more awareness that shifts in the age related work requirements will be consequential, especially for individuals in poorer health. While they could once rely on SNAP to provide a stopgap while they spent years negotiating the burdensome disability process, many will now find that access to SNAP has become dependent on that same burdensome process.